On Codex Seraphinianus, Communism, and the Freedom from Meaning

When the question “What’s does it mean?” is thrown at an artwork, it often leaves a messy stain. Try it with this book and you won’t even scratch the cover. It’s bulletproof.

I grew up in a fiercely deterministic culture that used art to inspire conformity, efficiency, and self-sacrifice. Everything that smacked of impracticality was considered decadent. Communists detested daydreaming with the same passion with which Catholics condemned masturbation—it was a gateway drug for moral decay.

Communism embraced the concept of historical materialism—a self-serving view of the past that not only legitimized its revolutionary ideology, but presented it as the only possible outcome of human progress.

It treated art in a similar fashion. Just like history progressed from slave owning empires to proletarian dictatorships, human art was on a path of relentless improvement: It was born in the dark prehistoric caves, got appropriated by religion, subjugated by the aristocracy, and commoditized by the bourgeoisie. Its ultimate destiny, however, was to serve the working class. If that sounds absurd to you, remember there’s only one fundamental difference between the emancipated slave and his former master—the first one is not yet capable of self-reflection.

A society where every creative impulse is ideologically regulated can indeed herald an ultimate point in history, albeit not as utopian as the communists imagined it. With their egos hollowed out, artists became mere craftsmen, destined to replicate stagnant forms, devoid of spontaneity. Inadvertently, art lost its ability to reflect and interpret reality. Whatever was left of it retreated back into the dark caves from which it originated.

Art as a Game

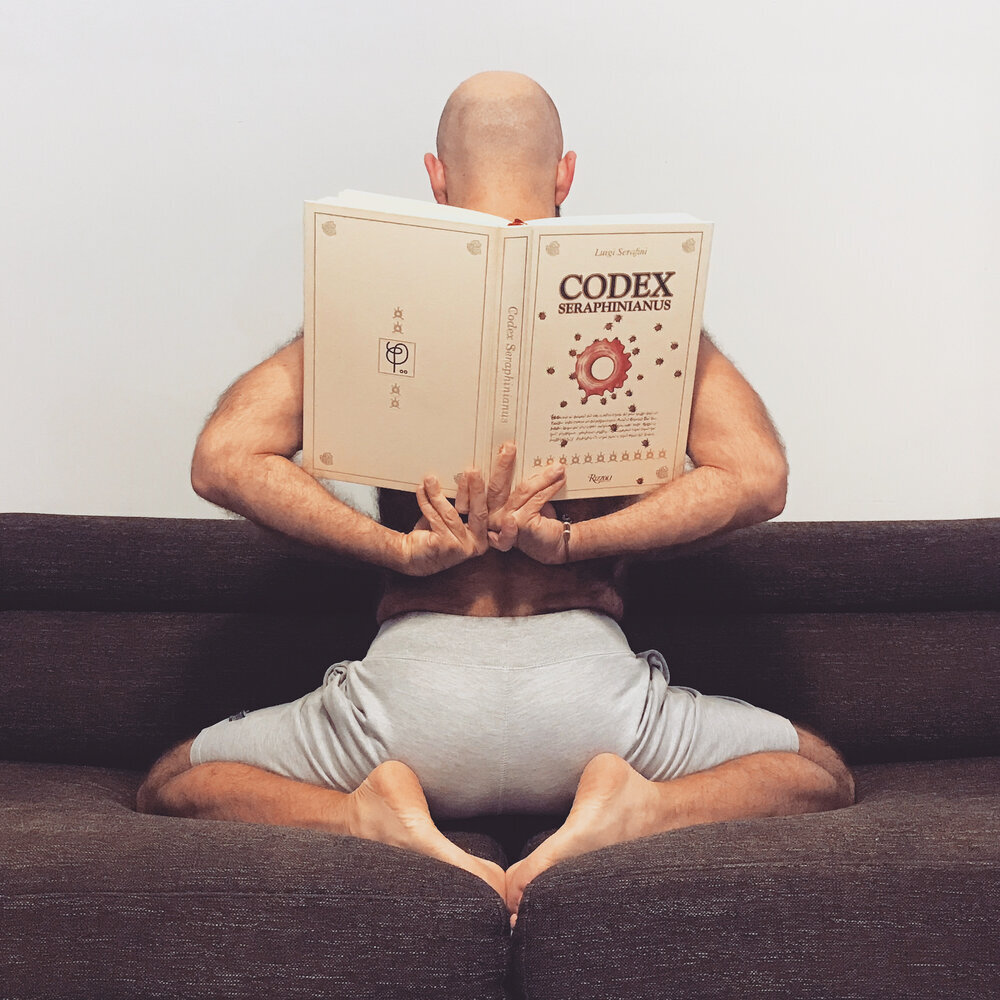

The format of this book allows you to read it while you’re practicing yoga on your couch as you can see from this spiritual selfie I took while deeply meditating on the purpose of art.

What I wrote so far must look like the most random digression in the history of book reviews. Alas, the grim preamble was necessary to explain why my deep appreciation of Codex Seraphinianus borders on fanaticism.

Of all books hypothetically eligible to be burned by a communist censorship committee, Luigi Serafini’s masterpiece would shine the brightest.

For one, it’s a luxurious hardcover, printed on thick, high-quality paper and can catch fire pretty easily. But more importantly, it’s jammed with surreal imagery that would sit nicely next to a coffee table book with works by Salvador Dali—the poster child of Western decadence.

Unlike Dali, who was a skillful prankster in his own right, Luigi Serafini took things further and—to add insult to injury—he applied a generous veneer of hazy symbolism, so the book would look as if it was meaningful. I can only speculate about his ultimate goal but to me, Codex Seraphinianus is a giant middle finger to everyone who has ever thought art had any sort of responsibility about anything.

“Many people tried to decipher the text creating decoders and computer software, but to me it is all too superficial. To decipher does not always mean to understand.”

“Do you remember how, when we were children,” writes the author in a small booklet, attached to the back cover of the Codex, “we’d leaf through picture books and, pretending we could read before the children older than us, fantasize about the images we saw there? Who knows, I thought to myself, perhaps unintelligible and alien writing could make us all free to once again experience those hazy childhood sensations.”

Mission accomplished.