Vanitas – Detailed Definition, History and Examples

Vanitas was an art form that began in the 16th and 17th centuries, which existed as a symbolic type of artwork that demonstrated the temporality and futility of life and pleasure. The most well-known genre to come out of the Vanitas theme was that of the still life, which was incredibly popular in Northern Europe and the Netherlands. Vanitas artworks came about during a time of great religious tension in Europe, as it emerged as a defender of the Protestant mission of introspection.

Table of Contents

- 1 What Is Vanitas?

- 2 Understanding the Vanitas Art Definition

- 3 Characteristics of a Vanitas Artwork

- 4 The Legacy of Vanitas Art

- 5 Famous Vanitas Artists and Their Artworks

- 5.1 Hans Holbein the Younger: The Ambassadors (1533)

- 5.2 Pieter Claesz: Vanitas Still Life with violin and glass ball (c. 1628)

- 5.3 Antonio de Pereda: Allegory of Vanity (1632 – 1636)

- 5.4 Jan Miense Molenaer: Allegory of Vanity (1633)

- 5.5 Willem Claesz: Still Life with Oysters (1635)

- 5.6 Judith Leyster: The Last Drop (The Gay Cavalier) (1639)

- 5.7 Harmen van Steenwyck: Still Life: An Allegory of the Vanities of Human Life (1640)

- 5.8 Joris van Son: Allegory on Human Life (1658 – 1660)

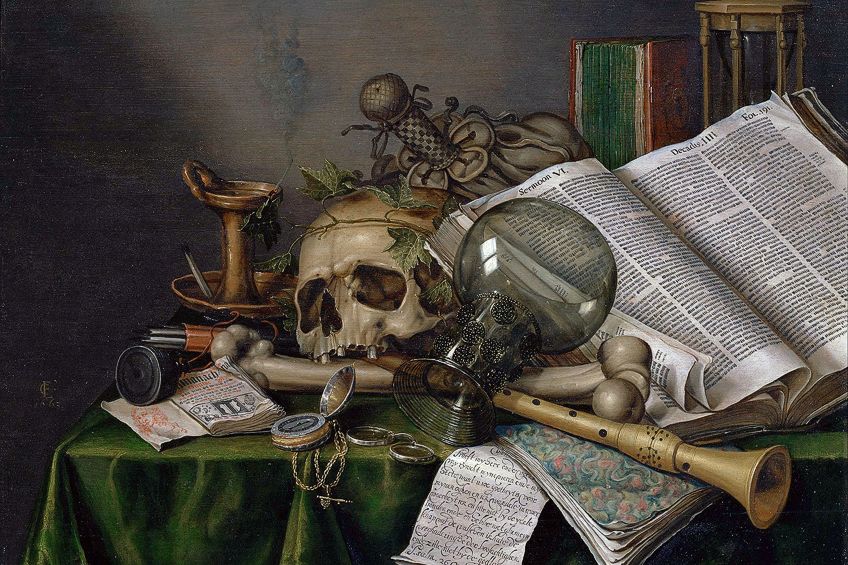

- 5.9 Edwaert Collier: Vanitas – Still Life with Books and Manuscripts and a Skull (1663)

- 5.10 Pieter Boel: Allegory of the Vanities of the World (1663)

What Is Vanitas?

Originating in the Netherlands during the 16th and 17th centuries, Vanitas became a very widespread type of Dutch master painting. The Vanitas genre made use of the still-life form in order to conjure up the transient quality of life and the vanity of living in the artworks that were produced.

At the time, great commercial trading wealth and regular military conflict consumed Europe, which provided painters with interesting subject matters and ideas to consider. Artists began to express an interest in the brevity of life, the meaninglessness of earthly delights, as well as the pointless search for power and glory. These themes were then overemphasized in the paintings that were made and went on to be considered as essential qualities in the Vanitas artworks that followed.

A very dark form of still-life painting flourished as the Vanitas theme began to rise in popularity, as the artworks aimed to remind viewers about their own impending mortality. Vanitas artists dedicated themselves to communicating to the affluent public that things such as pleasures, wealth, beauty, and authority were not unending properties.

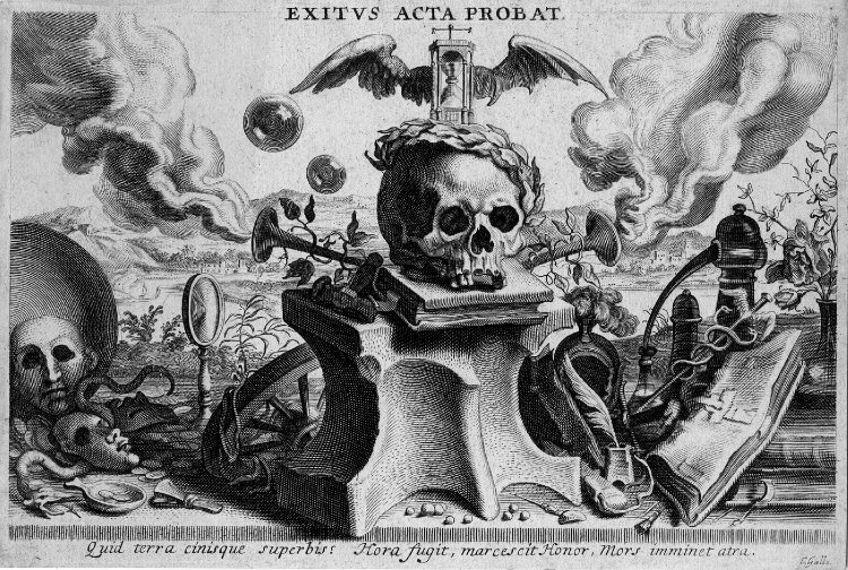

This stark reminder of impermanence was demonstrated by different Vanitas paintings through the inclusion of certain objects. Things that became commonplace within these paintings were worldly objects such as books and wine, which were placed next to meaningful symbols like skulls, shriveling flowers, and hourglasses. These objects all conveyed the theme of passing time within the paintings, which further emphasized the ever-present reality of mortality.

As the aim of Vanitas paintings was to demonstrate both the futility of worldly pursuits and the certainty of death, two types of painting styles existed. The first category included paintings that focused on death through the inclusion of objects like skulls, candles, burnt-out lamps, and wilting flowers. The second category, in an attempt to imply the inevitability of death, symbolized the fleeting nature of earthly pleasures with objects such as money, books, and jewelry.

Another important symbol that was used in both categories was the inclusion of hourglasses, open pocket watches, and clocks, which indicated the passing of time. These objects implored viewers to understand that time was a precious resource and subtly scolded those who seemed to be wasting theirs.

Thus, many Vanitas paintings combined both categories to create artworks that existed as symbols of both death and ephemerality.

At first glance, Vanitas paintings are incredibly striking, as their compositions are very chaotic and disorganized. The canvas is typically cramped with objects that seem random at first, but upon closer inspection, the type and proximity of the objects hold a lot of symbolism and exist as a stylistic choice.

Despite incorporating elements of still life, Vanitas paintings differ greatly due to them being very symbolic. Artists did not create paintings in an attempt to display various objects or demonstrate their artistic skill, as both traits became evident the more the painting was considered and observed.

The paintings created during this time existed as a symbolic depiction of the uncertainty of the world and emphasized the idea that nothing can possibly persevere against decay and death. Thus, Vanitas artworks implored a severe message, as the aim was to preach the thoughts and ideas of the genre to its viewers.

In addition to being popular throughout its time, Vanitas has continued to influence some of the artworks that are currently seen in post-modern artistic society. Well-known artists who have experimented with the Vanitas style include Andy Warhol and Damien Hirst, who made use of skulls within their artworks.

As with the modern depictions of Vanitas artworks that exist today, the message of the genre remains the same: This is the only life we are given, so do not let it pass you by before you are able to enjoy it to the fullest.

Understanding the Vanitas Art Definition

When looking for a definition, we should first understand the etymology of the term. The word vanitas is of Latin origin and was said to mean “futility”, “emptiness”, and “worthlessness”. Additionally, “vanitas” was closely related to the Latin saying memento mori, which roughly translated to “remember you must die”. This saying was said to exist as an artistic or allegorical reminder of the certainty of death, which justified the inclusion of skulls, dying flowers, and hourglasses in the Vanitas paintings that were created.

Thus, an appropriate Vanitas art definition would encompass artworks that speak to the inevitability of mortality and the pointlessness of worldly pleasure. This was essentially done through the inclusion of various symbolic objects that were designed to remind viewers about these ideas.

Vanitas Reminds Us of Vanities

The term vanitas was Latin for “vanity”. It was thought that vanity encapsulated the idea behind Vanitas paintings, as they were created to remind individuals that their beauty and material possessions did not exclude them from their inescapable mortality.

The term originally came from the Bible in the opening lines of the Book of Ecclesiastes 1:2, 12:8, which read, “Vanity of vanities, saith the Preacher, vanity of vanities, all is vanity.” However, in the King James version, the Hebrew word hevel was mistakenly translated to mean “vanity of vanities”, despite it actually meaning “pointless”, “futile”, and “insignificant.” Despite this mistake, hevel also implied the concept of transitoriness, which was an important idea within Vanitas paintings.

The Relationship Between Vanitas and Religion

Vanitas paintings were seen not only as a mere work of art, but they also carried significant moral messages that saw them being considered as a type of religious reminder. The paintings were primarily designed to remind those who looked at it about the triviality of life and its pleasures, as nothing could withstand the permanence that death brought.

Due to its subject matter, it is debatable whether the Vanitas genre would have been as popular if it were not for Counter-Reformation and Calvinism, which thrust it into the spotlight. Both of these movements, one Catholic and the other Protestant, appeared at the same time that Vanitas painting began to rise in popularity.

Today, critics attribute the arrival of these movements as additional cautions against the vanities of life, as they stressed the reduction in possessions and triumph, which further emphasized what the Vanitas genre stood for.

The Influence of Protestantism

The Protestant Reformation that occurred in the 16th century caused a remarkable shift in religious thought throughout Europe. The continent began to split itself up between Catholicism and Protestantism, which introduced much uncertainty to many religious issues. This led to the Catholics advocating for the eradication of holy images, while the Protestants believed that these images could be beneficial for individual reflection of God and other holy subjects.

The Dutch Republic, which was freeing itself of its Catholic Spanish rulers, became a proud Protestant state by the beginning of the 17th century. The individualistic feeling towards deliberation that accompanied Protestantism helped direct Dutch artists towards the genre of Vanitas, as they wanted to express their religious sentiment through the appropriate art form.

The Vanitas genre was thus built on Protestant ethics, as demonstrated by the ideas and themes that came forward in the paintings created. Vanitas reminded individuals that despite the appeal of worldly things, they remained ephemeral and inadequate in relation to God. Thus, these paintings emphasized the inescapable mortality that viewers faced, in an attempt to remind viewers to act in accordance with God.

Vanitas and Realism

Vanitas art was incredibly realistic, as it was firmly grounded in Earthly concepts which differed greatly from the mystical technique of Catholic art. Therefore, this genre of Vanitas art was instrumental in guiding the focus of the viewer’s mind towards Heaven through the depiction of objects that existed on Earth.

Realism is also noticeable in Vanitas paintings as they were extraordinarily intricate and specific. A closer examination of the artworks revealed the heightened skill and devotion of artists, as they highlighted objects of the viewer’s life in an attempt to make the painting as relevant and applicable as possible.

Through making use of a realistic style, the Vanitas artist was able to isolate and then stress the main message of the artworks, which centered around the vanity of mundane things. Realism within these artworks helped viewers to understand and subsequently order their minds with reference to the fleeting aspects of life, which contrasted greatly against the disorder of the actual painting.

Vanitas and Still Life

One of the most important aspects of the Vanitas genre was that it was considered to be a sub-genre of still life painting. Thus, Vanitas paintings were simply a variation of the traditional still life form. Typical still-life paintings consisted of inanimate and ordinary objects, such as flowers, food, and vases, with the attention of the artwork being placed on these objects alone.

However, a Vanitas still life painting made use of these objects traditionally found in a still life in order to emphasize a completely different idea.

The Vanitas still life was said to teach viewers an important and moral lesson, as artists placed common vanities in contrast with an individual’s eventual death. This was done to initially appeal to viewers before humbling them with regards to how they treat others and the world once having fully considered and understood the work.

Characteristics of a Vanitas Artwork

Within the Vanitas paintings that were created, certain characteristics appeared that enabled its inclusion into the genre. These characteristics centered around the themes and motifs that were explored in each artwork, which are discussed below.

Themes

The themes that were present in the Vanitas paintings that were produced had a lot in common with medieval commemorations of the dead. Prior to this genre of painting, this obsession with death and decay seemed morbid. However, after overlapping with the Latin phrase memento mori, these themes within paintings slowly became more indirect and therefore acceptable.

As the still life genre rose in popularity, so did the Vanitas style. Its themes, while still shocking and bleak to viewers, were becoming easier to understand, as they were only used to remind viewers about the temporality of life and pleasures, as well as the factual assurance of death.

In addition to its core principles, the style of Vanitas art presented a moral justification for painting attractive objects in macabre settings. This was because the message that the paintings were trying to get across was much more important than the actual objects themselves.

Motifs

Several motifs exist that were fundamental to the Vanitas genre. Depending on the geographic location of the painting, as different regions showed a preference for different motifs, artists would emphasize a variety of distinct motifs.

Numerous symbols were represented within Vanitas paintings, with the same type of motifs used for each category. The motifs that were used to portray wealth included gold, purses, and jewelry, while those used to describe knowledge incorporated books, maps, and pens.

The motifs that were used to depict representations of pleasure took on the form of food, wine cups, and fabrics; and the symbols of death and decay were typically represented by skulls, candles, smoke, flowers, watches, and hourglasses.

Symbolism Within Vanitas Paintings

The most important symbol that was ever-present within the numerous Vanitas paintings was the awareness of man’s mortality. No matter what other objects were included, the reference to mortality was always made clear. Most often, this was depicted through the inclusion of a skull, but other objects such as wilting flowers, burning candles, and soap bubbles achieved the same effect.

Symbols relating to the concept of time were also included, which were typically portrayed through using a watch or an hourglass. While decaying flowers may speak to death, they also imply the passing of time, allowing them to be used for both concepts. However, the concept that Vanitas paintings possibly evoke the most, in addition to mortality, is the harsh truth.

Within the Vanitas still life artworks that were made, the hopelessness of our mundane pursuits in the face of our mortal existence was explored.

The Legacy of Vanitas Art

Towards the end of the Dutch Golden Age, the Vanitas art genre began to lose its public popularity. This was due to the fact that the meaning behind what Vanitas stood for lost its power, in addition to the spirit of the religious combative reform losing its force. However, the developments that occurred in still-life painting during this time would go on to have a great influence on the generations of artists to come.

Interestingly, Vanitas was said to have been borne from a contradiction itself. Through the act of painting and subsequently creating a beautiful artifact, a vanity was created that warned viewers against the dangers of other vanities in life. Thus, Vanitas remained a significant art genre during the 17th century, as it guided and focused the minds of individuals towards ideas that reflected death and the seemingly worthless yet exuberant act of living.

What continued in the footsteps of Vanitas was the addition of aesthetic beauty to artworks. After Vanitas came to a close, still lifes were astonishingly beautiful in their depiction until they underwent another change in meaning towards the end of the 19th century. This was primarily led by artists Paul Cézanne and Pablo Picasso, who began experimenting with the different aesthetics that the still life composition had to offer.

Famous Vanitas Artists and Their Artworks

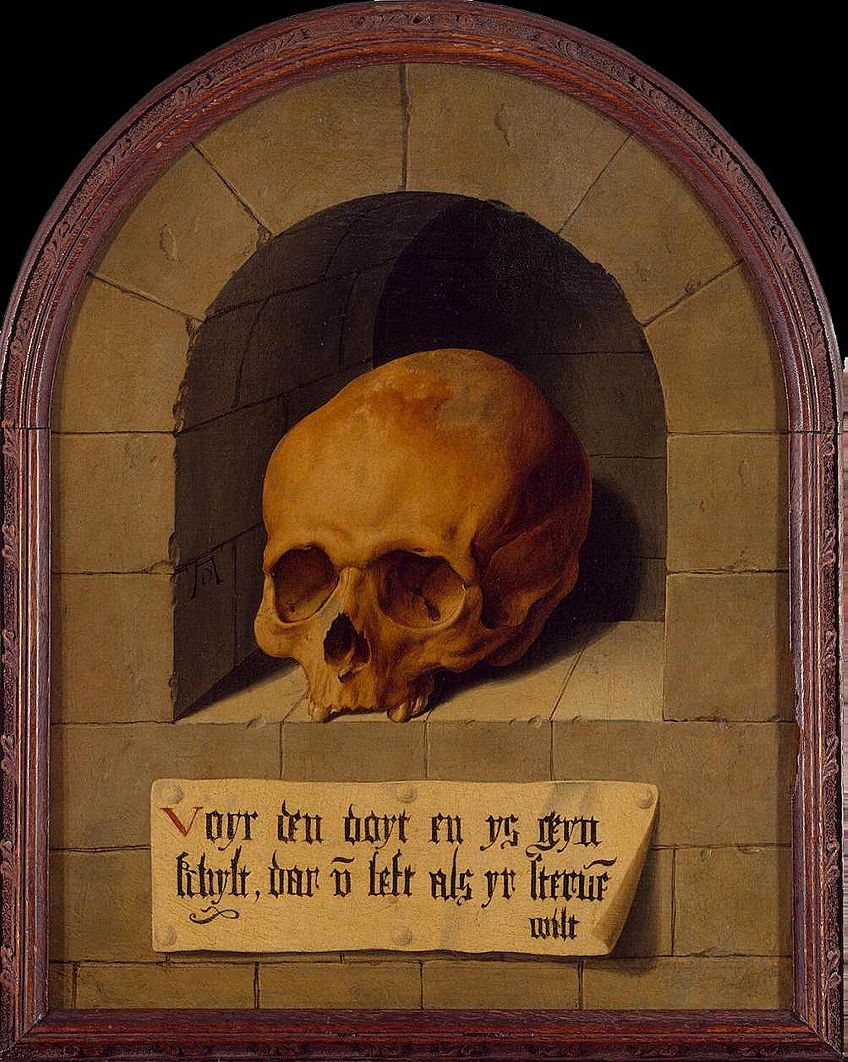

Vanitas paintings first started out as still lifes that were painted on the back of portraits as a direct and clear warning to the subject about the impermanence of life and the inevitability of death. Eventually, these warnings evolved into a genre of their own and became featured works of art.

At the start of the movement, the artworks appeared to be very gloomy and dark. However, as the movement rose in popularity, the artworks started to lighten up slightly towards the end of the period. Viewed as a signature artistic style of Dutch art, a number of artists became well-known for their Vanitas artworks. In the list below, we will explore some of the most famous and influential artworks from the Vanitas period.

Hans Holbein the Younger: The Ambassadors (1533)

Painted by the German Hans Holbein the Younger, The Ambassadors existed as an important precursor for the Vanitas genre. In this artwork, Holbein depicts the French ambassador of England and the bishop of Lavaur, with these two men leaning against a shelf adorned with Vanitas symbols.

Pieter Claesz: Vanitas Still Life with violin and glass ball (c. 1628)

One of the greatest painters of the Dutch Golden Age was Pieter Claesz, who painted Vanitas Still Life with violin and glass ball. This artwork displayed Claesz’s artistic mastery when it came to depicting several Vanitas motifs.

Antonio de Pereda: Allegory of Vanity (1632 – 1636)

Very little is known about Spanish artist Antonio de Pereda, who painted one of the most well-known Vanitas still lifes. This artwork, titled Allegory of Vanity, elegantly hints at the pointless quest for power, as demonstrated by the angel who is surrounded by exquisite goods. Next to her lies money and fine jewelry, yet the angel seems oblivious to this wealth. It is as if she understands the hidden meaning that the painting attempts to convey before the viewers are able to figure it out.

Jan Miense Molenaer: Allegory of Vanity (1633)

Allegory of Vanity, painted by Jan Miense Molenaer, is said to exist as an excellent example of Vanitas art. This artwork depicts three individuals thought to be a woman, her son, and her servant. Multiple symbols exist within this painting that allude to themes of luxury, extravagance, and satisfaction. These ideas are depicted by the musical instruments, the ring on her finger, the map hanging on the wall in the background, as well as the clothes the mother and son are wearing.

Willem Claesz: Still Life with Oysters (1635)

Dutch painter Willem Claesz was known for his innovation in his still-life depictions, which he painted exclusively throughout his career. Within Still Life with Oysters, an unusual take on Vanitas paintings is done. The reason for this is that no seemingly obvious Vanitas symbols and objects are included. Instead, Claesz simply depicted objects of wealth, such as oysters, wine, and a silver tazza.

Judith Leyster: The Last Drop (The Gay Cavalier) (1639)

The Last Drop, painted by Judith Leyster, offers a unique example of Vanitas paintings during the time. Two men, who are perceived to be gay based on the title of the artwork, are portrayed to be surrendering their pleasures through drinking and dancing.

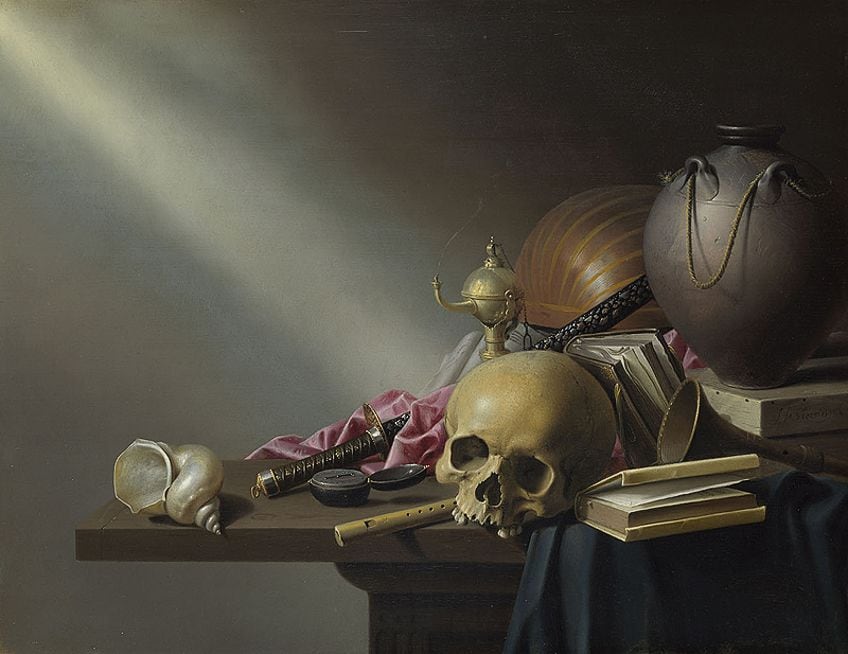

Harmen van Steenwyck: Still Life: An Allegory of the Vanities of Human Life (1640)

Dutch painter Harmen van Steenwyck was among the leading artists of the Vanitas genre and went on to become one of the best still-life painters of his time. Still Life: An Allegory of the Vanities of Human Life exists as a prime example of Vanitas painting, as it was actually a religious work disguised as a still life.

Joris van Son: Allegory on Human Life (1658 – 1660)

Flemish artist Joris van Son, who painted Allegory on Human Life, addressed the Vanitas theme in an aesthetically beautiful style. Upon first glance, one is instantly captured by the beauty of this artwork, as depicted by the abundant array of flowers and fruits. The colors used within this painting add warmth, which make the roses, grapes, cherries, and peaches look even more exquisite than what they appear to be.

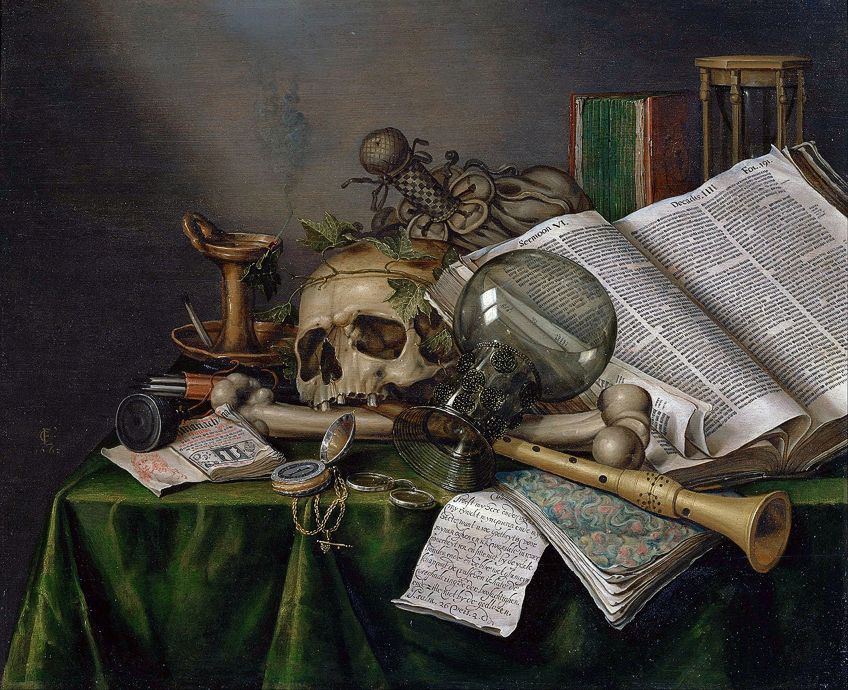

Edwaert Collier: Vanitas – Still Life with Books and Manuscripts and a Skull (1663)

Dutch Golden Age painter Edwaert Collier was mostly known for his still lifes, as demonstrated by his impressive artwork titled Vanitas – Still Life with Books and Manuscript and a Skull. Notably significant as a Vanitas artist, Collier was only 21 years old when he painted this work, demonstrating the great artistic talent he possessed.

Pieter Boel: Allegory of the Vanities of the World (1663)

Pieter Boel, another important Flemish Vanitas artist, specialized in lavish still lifes throughout his career. His Allegory of the Vanities of the World is thought to be a masterpiece of the Vanitas genre, due to its attention to detail and unusually large size.

When considering the different paintings that made up this genre, it is easy to still wonder: What is Vanitas? At its very core, the Vanitas period within art focused on creating artworks that emphasized the transience of life and the unavoidability of death to viewers. Thus, the message in Vanitas paintings was that although the world can be apathetic towards human life, its beauty can still be enjoyed and reflected upon before the eventual decay of death takes place.

Take a look at our Vanitas still life art webstory here!

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Vanitas – Detailed Definition, History and Examples.” Art in Context. May 10, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/vanitas/

Meyer, I. (2021, 10 May). Vanitas – Detailed Definition, History and Examples. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/vanitas/

Meyer, Isabella. “Vanitas – Detailed Definition, History and Examples.” Art in Context, May 10, 2021. https://artincontext.org/vanitas/.