For the past year, in the U.S., a fairly renown critic, A. D. Coleman, has been analyzing and deconstructing the famous photographs Robert Capa took on D-Day in Normandy. He started out with a very technical investigation focusing on facts: the time spent on the beach; the number of films used and of frames shot; the unlikeliness of the version explaining the destruction of most of the photographs because of overheating. Such findings appear to be indisputable. His analysis then tackled the subsequent construction of the Capa myth –as did the French scholars who first relayed Coleman’s works. Again, it seems there is nothing to oppose to this, save for, maybe, some excessive hostility in the choice of words, infringing on the (my) rules of courtesy. Coleman’s remarkable deconstruction has allowed for further inquiry into the Capa myth, which had already been challenged by rising doubts over the famous Spanish photograph. All of this does not negate Capa’s talent or his contribution to photojournalism, yet it does reinforce the doubts about his character and the construction of his legend.

All things considered, these debates have addressed topics related to technique and to the construction of the myth, topics that are important to the community of photography and visual culture historians and critics, yet topics with no political dimension. I was surprised to see that another facet of Capa’s work completely failed to interest those critics in search of the truth, so quick to deconstruct some myths and to question seemingly obvious truths, but apparently not so inclined to venture on the –probably more dangerous– political side of things to face off myths of a much more powerful nature.

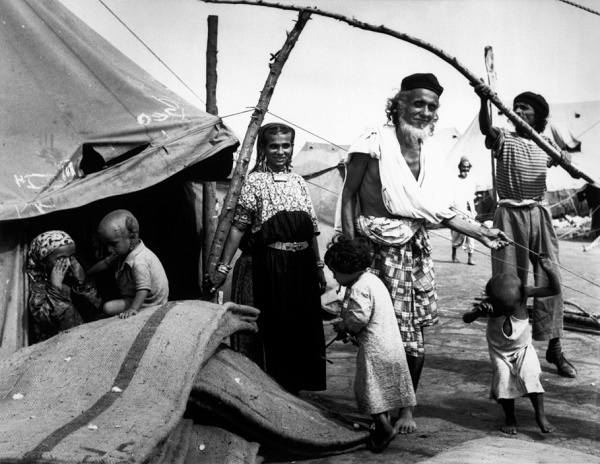

Robert Capa, Haifa. After arriving in Israel, immigrants are sent to reception camps, until housing is found for them.

Between 1948 and 1950, Capa went to Palestine/Israel to report on the proclamation of independence of Israel (Ben-Gurion waited for him to be there and ready to photograph before launching into his historic speech), on the war, on the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians from the new territories of the Hebrew state, and on the construction of this state. Did Robert Capa do so as an objective journalist, reporting on the facts, the fighting, the evictions, in the most neutral way possible? Did he work according to the general guidelines of photojournalism (such as the ones in use at Magnum, which he was co-founding at the time)? Did he put to question the information he was getting from one side, his hosts? Did he strive to take into account the views of the other side? Did he keep a critical mind in front of those who helped and guided him, or did he settled on relaying only one vision of the conflict (as the likes of Fenton and Beato have been doing since the early days of photojournalism)? In short, did he work as a journalist or as a propagandist?

Certainly, this is a hard topic to tackle when one thinks about the weight of the adverse party’s discourses, its lobbies, its relays at the highest levels of our states. Whoever dares to confront this risks making waves, which will compel him/her to fend off a tried and tested strategy, the oft-used accusation of anti-Semitism which endlessly erupts as soon as such myths are challenged (which might also erupt in the comments to this blog post), and which then might damage his/her career. To my knowledge, only two American scholars, Andrew L. Mendelson and C. Zoe Smith have had the courage to do so, publishing their research in 2006 in the journal Journalism Studies, after having presented it at an academic conference in 2002. (They both teach Journalism –him at Temple University, her at the Missouri School of Journalism– and not Photography History or Visual Studies, which might explain things.) To my knowledge, for the past nine or thirteen years, nobody has relayed their findings in France (whereas Coleman’s were swiftly echoed). To my knowledge, only a few Israeli scholars dared to relay them (but the commitment of Ilan Pappé’s and Ariella Azoulay’s disciples in the face of the dominant ideology of their country has already been proved).

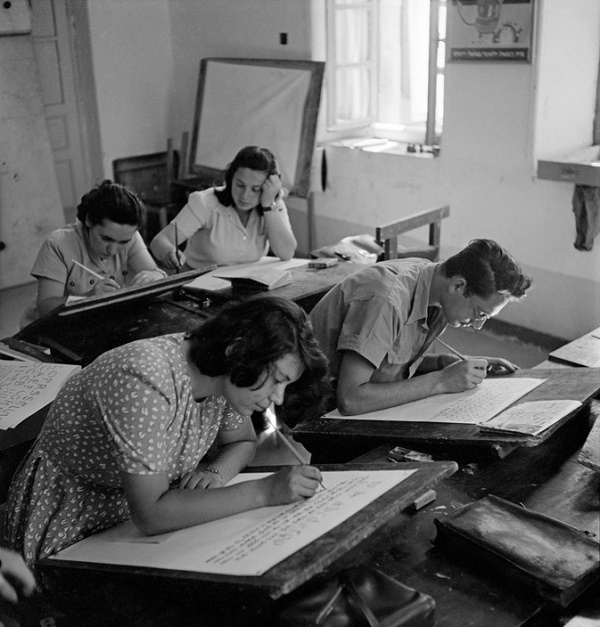

What are Smith and Mendelson saying? First, they restate some obvious tenets of journalistic ethics: impartiality, objectivity, neutrality (as early as 1936, James C. Kincaid asserted that: “Press photography must avoid any kind of biased opinion”), and they stress the importance of systematically taking into account the “social location” of the photographer vis-à-vis his/her subjects. They also note that the seemingly objective nature of photographs actually makes them all the more efficient to represent, propagate and reinforce myths. The scholars’s semiotic study focuses on photographs that Capa published in magazines and books between 1948 and 1951. They did not include “The Journey” –the openly propagandistic movie that Capa shot in 1950 for a Zionist organization, The New York United Jewish Appeal–, for they consider it an expression of Capa’s personal views and, indeed, it does not fall under the category of journalistic work. (Conversely, they overlooked Israeli archives, which would surely bring along interesting information.) Mendelson and Smith then briefly recount Capa’s life, pointing out in passing how, in the 1930s, Endre Erno Friedmann changed his name to Robert Capa (a name with as little “identity” as possible), in part to hide his Jewish origins, and how he nevertheless embraced Zionism wholeheartedly after World War II, deciding to go to Palestine/Israel on his own dime, without any contract. Another interesting fact is that Capa suffered an injury to his thigh on June 22, 1948 (the only time he was ever wounded, unless I am mistaken, before his death in Indochina), not because of Arab bullets, but because of the fighting on the Altalena between Menachem Begin’s terrorist paramilitary group Irgun and Israel’s regular army (see picture above). Mendelson and Smith also remind us that another Magnum co-founder, George Rodger, was in the country as well but reporting on the Arab side (Rodger spoke Arabic), and, contrarily to Capa, how difficult it was for Rodger to sell his photographs of Palestinians being evicted and villages being destroyed. Only one German magazine agreed to publish them: indeed, “almost all the publishers of American magazines were Jewish,” Rodger explained in Russell Miller’s historic book on Magnum (1999). Furthermore, Capa criticized Rodger for his lack of objectivity, declaring that “Rodger has taken a side, something a journalist should never do,” according to Rodger’s biographer, Carole Naggar. A case of irony and/or bad faith…

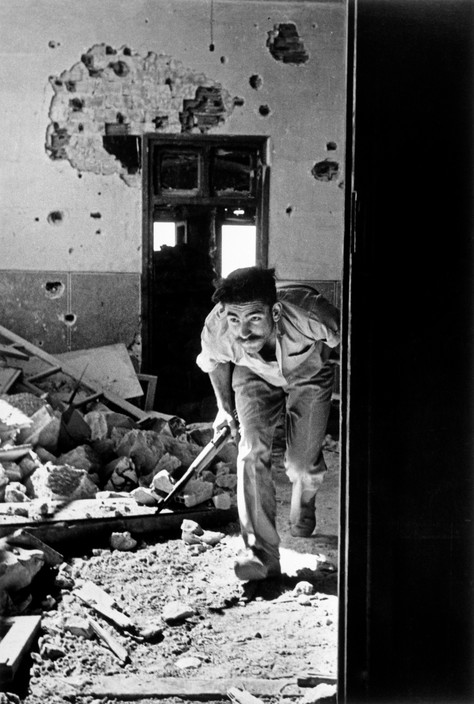

Robert Capa, Jerusalem. June 9th, 1948. A member of the Israeli government forces, the Haganah, in a building surrounding the old city, held by the Arabs.

After these elements of context, Mendelson and Smith expose how the creation of the State of Israel relied on the construction of a mythic narrative that was to be presented as objective history. They identify three main myths (that are actually still used by Zionist propaganda today), and they analyze in great detail how Capa’s photographs have supported and reinforced these myths. First myth: Israel defends civilization (Western civilization, of course), and Arabs are uncivilized attackers. This neo-colonialist fiction is well-known, and still in use. In Capa’s photographs, there are almost no Arabs, although the population was predominantly Arab then. Moreover, the few Arabs depicted (only four occurrences confirmed, it seems) are shown vanquished, imprisoned, wounded, seen from afar, and in stereotypical fashion. The only Arabs who are photographed in the same way as Jews (in “noble” portraits) are Druzes from Galilee, who fought alongside Israel. There are no expropriated or destroyed Arab villages in the photographs, no victims of massacres and rapes, no visible sign of the ethnic cleansing in play.

Second myth: the Sabra, heroic pioneer and soldier. Here as well, the myth of the New Man is well-known, even if the myth has shifted today towards high technology and even homosexuality-related “pinkwashing.” Capa’s photographs relentlessly show us “heroes” such as the smiling soldier and the determined worker, gleefully engaging in teamwork; that is to say, everything that reinforces the image of the Sabra as a complete opposite to the Jew of the Ghetto. Many of those photographs feature low-angle shots, which echo ideas of strength and nobleness.

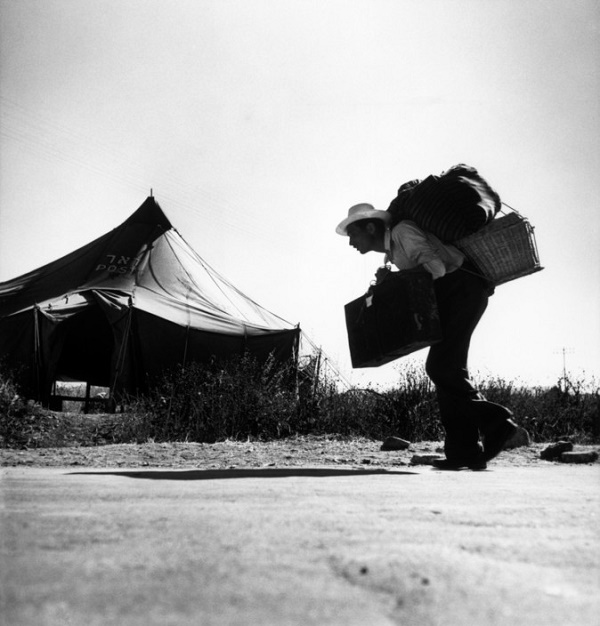

Third myth: the Promised Land. Once again, the exploitation of Biblical texts by the Zionist ideology comes as no surprise: a people without a land arriving on a land without people, the Return of the diaspora (to deconstruct this myth, we had to wait for Shlomo Sand), and the inalienable right to the land of the “ancestors.” Capa’s photographs (and their captions) emphasize ceaselessly this link with the Promised Land, reinforcing this myth of the Return and staging the seminal re-appropriation of the land.

Robert Capa, Shaar Aliya. 1950. Experimental planting near Red Sea to test productivity in arid soil.

In conclusion, Mendelson and Smith are positive Capa’s work contributed to the legitimization of the creation of the State of Israel, as well as to the de-legitimization of its opponents, and first among them the Palestinians inhabitants evicted from their land. Indeed, Robert Capa’s photographs give life to abstract concepts and therefore lead the viewer to the indisputable conclusion that the creation of Israel was rooted in history and had to happen. The photographer’s promotion of Israel’s founding myths falls in line perfectly with the constant propaganda (“hasbara”) still in place today.

Robert Capa, Haifa. 1949. Upon their arrival, immigrants are placed in reception camps, until housing is found for them.

Mendelson and Smith’s analysis allow for a great reevaluation of the purported objectivity of journalism. Moreover, it shows how viewers can be “manipulated” by photojournalists (and by editors, a topic the study only brushes). Also, it chips away at Capa’s myth after the Spanish war and Omaha Beach controversies. Finally, and above all, the lack of impact this study has had, despite its relevance, shows just how much the people who should be our interpreters and guides (art historians, Visual Studies specialists, Journalism scholars…) struggle –or hesitate– to engage some –and only some– myths. Alas…

All photographs are taken from Magnum’s website: © Robert Capa © International Center of Photography/Magnum Photos

Read this article:

in the original French; alt.

in Spanish

Original publication date by Lunettes Rouges: October 13, 2015.

Translation by Lucas Faugère

Pingback: Robert Capa au service des mythes fondateurs de l’état d’Israël | lunettesrouges1

Maybe I’m too brainwashed by “zionist propaganda” (have you ever looked at it as a narrative rather than an intentional attempt to show things a certain way?) but I do not remember one instance in which Capa’s great photographs hadn’t revolved around a solid ideology of his. He always showed things from his point of view while utilising connections with officials in the side he favoured and found more just. This has been the case with both the Republicans and the Allies. I also don’t find his sympathy for the Israeli-Jewish narrative that shocking; after all, Capa was a jewish refugee himself! With that being said, thank you for the comprehensive article, I enjoyed it very much.

[I don’deny that it is a narrative, I just say that it is a colonial narrative. And, precisely, having been a refugee doesn’t grant a right to justify an ethnic cleansing that will create other refugess, in my view]

LikeLiked by 1 person

You have said it very well, Israel needed to be formed and thank God it was.

[You can thank God all you want. I don’t think that the Palestinians victims of this ethnic cleansing feel the same]

LikeLiked by 1 person