Auricular ornament in Dutch Architecture (1610-1675)

Dr Pieter Vlaardingerbroek examines evidence of the Auricular style in the Netherlands and the means of dating it more accurately through Dutch architecture and architectural artefacts, and through sculptural objects such as pulpits and tombstones.

Hendrick de Keyser, bust of a unknown man, 1606. Photo: Rijksmuseum

Introduction

When speaking about Auricular ornament in Holland, most art historians refer either to works of art in silver and other metalwork from the first decades of the 17th century, or to the revival of the style as it can be seen in picture frames and furniture from the third quarter of that century. Generally, this revival is seen as the consequence of the issue of ornamental prints around 1650, made by the silversmiths Christiaan van Vianen, Johannes and Jacob Lutma, and by Gerbrandt van den Eeckhout, painter and son of an Amsterdam goldsmith. When describing the history of the style in this way, it seems as if there is an absence of Auricular ornament between 1600 and 1650 in all kinds of art except for that in metal. Some art historians even go so far as to proclaim that Auricular ornament in other materials than metal is virtually impossible.

This idea can be found in Framing in the Golden Age, and in the exhibition catalogue Dawn of the Golden Age: Auricular ornament

‘remained limited to the realm of the cartouche in the graphic arts and to most exclusive works in silver’. [1]

Both publications claim strapwork remained dominant in the other arts, and

‘it was not until much later in the century, around 1650, that this type of [Auricular] ornamentation appeared in picture frames, tables and chests’. [2]

The same opinion can also be found in Form and decoration by Peter Thornton:

‘So, while the fresh and exciting first fruits of fully developed Auricularism were to be seen in metalwork during the second and third decade of the century, other manifestations of the style were mostly produced in the third quarter of the century’. [3]

When looking at ornamental prints and most picture frames, this general idea seems to hold some truth – even though one could raise one’s eyebrows when art historians claim that the carved (name) sign in Auricular style belonging to a painting by Bartholomeus van der Helst from 1648 can not be contemporaneous with it:

‘if indeed they were carved, this would contradict our finding that Auricular frames originated in the early ’50s’ .[4]

Figure 1: Anonymous maker, Sign belonging to Bartholomeus van der Helst, Banquet at the Crossbowmen’s Guild in Celebration of the Treaty of Münster, 1648 (and detail), Rijksmuseum, on long term loan from the City of Amsterdam. Photo: Rijksmuseum Amsterdam

Johan ter Molen, perhaps the foremost connoisseur of Auricular ornament, expresses a similar opinion in his essay on the Auricular, and in his dissertation on the Van Vianen family [5]. One of the first scholars claiming to see a time gap between the early and later Auricular style was C.H. de Jonge in 1915 [6]. She saw Auricular art depicted in works by Jan Steen and H. van der Mijn; she dated all tables and furniture with Auricular ornament to around 1660-1680.

Some other Dutch publications dating from the beginning and middle of the 20th century follow the earliest writings on Dutch Auricular style, which were produced by two Germans, Carl Neumann and (especially) Walther Zülch. Zülch’s ground-breaking book, Entstehung des Ohrmuschelstiles, describes the origin of the style, which gave him the freedom to show all the ingredients that led to it, starting with the grotesque in Italy, and including Federico Zuccaro, Hendrick Goltzius and strapwork. The Haarlem painter Goltzius was an important link in the creation of Auricular ornament: ever since Neumann wrote about Auricular style in his monograph on Rembrandt in 1901, Goltzius has been cited as the link between Italy and Holland; both Zülch and Neumann see him as the ‘inventor’ of the ornament currently known as Auricular. In his print of Bacchus (and in many cartouches on other prints) Goltzius shows a bowl with characteristics of the style [7].

The influence of these works can be found in Dutch publications from around the middle of the 20th century. Lunsingh Scheurleer implies in his Rijksmuseum Furniture Catalogue the existence of Auricular ornament in furniture from the 1630s and 1640s [8]. He believed that the tester bed in Auricular style in Rembrandt’s Danaë (1636) was a real piece of furniture, owned by the painter himself. Van der Pluym indicated that around 1630 strapwork was replaced by Auricular ornament, which itself disappeared after 1660 [9]. Still, very few examples are given of early examples in the Auricular, executed in three dimensions. The dissertation of Antje-Maria von Graevenitz does mention some earlier examples of the ornament in architecture [10]. A tombstone in the Pieterskerk in Leiden served as an example from the 1620s, although we could ask ourselves whether this really is an Auricular ornament or a further development of strapwork.

Which of the two groups of academics is right? This question is difficult to answer. The case might be that both groups have a different view on what Auricular ornament is. The first group of Dutch scholars limit it to the pure style of the Van Vianens and Lutma, making it more a less a Dutch national style. The second group incorporates the development towards this ‘high’ Auricular style, and by doing so, they have a more international view of Auricular ornament. This tendency of placing the Dutch Auricular style within the context of a wider international movement is also apparent in publications by Peter Thornton[11] and Peter Fuhring [12]. Fuhring describes different groups within the Auricular family as ‘German’, ‘French’ and ‘Italian’ Auricular, while the Dutch variant is just called ‘Auricular’.

In this essay I will give an overview of Auricular ornament within Dutch architecture and architectural artefacts. As many artefacts such as picture frames and furniture are undated, this might give a clearer view on the use of Auricular through time.

Architecture and Auricular ornaments

Figure 2: Amsterdam, 506 Herengracht, 1685. Photo: the author

Auricular ornament is – apart from cartouches – rather rare in Dutch buildings. One excellent example is the scrolled gable of 506 Herengracht in Amsterdam, with its sculpted top, comprising two triangular parts in which a leg of an animal continues upwards to end in scrolls (1685).

Figure 3: Leiden, Weigh House. Photo: Dutch Cultural Heritage Agency

Figure 4: Boer, Dutch Reformed Church, entrance. Photo: Dutch Cultural Heritage Agency

Auricular ornament on façades is usually applied in cartouches or oeils-de-boeuf, either in the top of a scrolled gable or situated in the tympanum of a pediment. Two examples of sculpted tympani stand out from the crowd. One is located in Leiden in the Weigh House, in the pediment of the shed, and was made by the Leiden sculptor Gerrit Goosman[13]. The other one is in Boer, a Frisian village, where the pedimented entrance has a similar (but rather less elegantly carved) tympanum [14].

Figure 5: Amsterdam, 386 Herengracht, 1663. Photo: Dutch Cultural Heritage Agency

In Amsterdam several hundreds of oeils-de-boeuf can be found, and it is likely that master bricklayers and carpenters were being taught how to design them. These oeils-de-boeuf are usually seen as the offspring of prints by Lutma, Van Vianen and Van Eeckhout, even though their design usually lacks the three-dimensional fleshiness of these prints. Ter Molen mentions several examples from the 1650s, especially within the work of the architect Philips Vingboons. References are made to Herengracht 59-61-63 (1659, 1665-66) and Herengracht 386 (1663).

Figure 6: Amsterdam, 364-370 Herengracht (Cromhout houses), 1661. Photo: Dutch Cultural Heritage Agency

Other well-known examples are Herengracht 364-370 (1660-62), also designed by Vingboons [15].

Figure 7: Gerrit Berckheyde, View on Kloveniersburgwal and the Trippen house, 1685. Photo: Andreas Borowski, private collection

Figure 8: detail of the Trippen house façade. Photo: the author

His brother Justus Vingboons was responsible for designing the Trippenhuis (1660-1662) with its pilastered façade, covered with cartouches and lambrequins below the windows in a fully-developed Auricular style.

Figure 9: Philips Vingboons, 319 Keizersgracht in Amsterdam, 1639, taken from Afbeelsels der voornaemste gebouwen uyt alle die Philips Vingboons geordineert heeft, Amsterdam 1648. Photo: the author

Figure 10: 319 Keizersgracht, detail. Photo: City of Amsterdam

Strangely enough, the Auricular ornament in his earlier work has never been noticed, even though he used very similar oeils-de-boeuf from the 1630s onwards: Keizersgracht 319 (1639) has an example.

Figure 11: Philips Vingboons, design for an internal portico for Huydecoper house, 1639. Photo: Het Utrechts Archief

Vingboons also used these details on porches within the house, as can be seen in a design for the house of Joan Huydecoper (1639) [16].

Figure 12: 69 Oudezijds Achterburgwal Amsterdam, 1645. Photo: the author

Other houses also have early specimens of Auricular oeils-de-boeuf, as Oudezijds Achterburgwal 76 shows (dated 1645; architect unknown).

Figure 13: Utrecht, Brunten alms houses, 1621. Photo: Dutch Cultural Heritage Agency

Figure 14: Adam van Vianen, tazza, 1610. Photo: Rijksmuseum

Outside Amsterdam, earlier examples can be found. An interesting specimen is the gate of an almshouse in Utrecht, home town of the Van Vianen family. The Bruntenhof (1621) has a Doric gate with three cartouches with Auricular features; the large one in the frieze even resembles elements from the Adam van Vianen tazza of 1610, now in the Rijksmuseum. Another, and probably more important, source of influence for architects and stonemasons was to be found in prints and books.

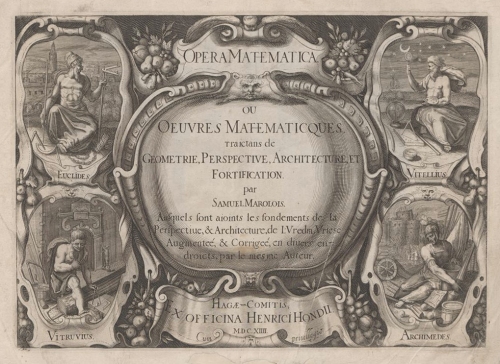

Figure 15: Samuel Marolois, Oeuvres Mathematicques traictans de Geometrie, Perspective, Architecture et Fortification, The Hague, 1614. Photo: ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Rar 9726 GF

One example was that essential mathematical textbook by Samuel Marolois, Oeuvres Mathematicques traictans de Geometrie, Perspective, Architecture et Fortification. Its publisher, Hendrick Hondius, published many editions with title pages filled with Auricular cartouches.

Figure 16: Haarlem town hall, balcony, 1630. Photo: Dutch Cultural Heritage Agency

In Haarlem we find two interesting examples of Auricular cartouches. The first is on the balcony of the town hall, dated 1630 and very much in the German tradition of the style. The painter and architect Salomon de Bray was probably responsible for its design.

Figure 17: Haarlem, Meat Hall, 1602-03. Photo: Dutch Cultural Heritage Agency

Figure 18 Haarlem, Meat Hall, the city´s coat of arms, 1602-03. Photo: Dutch Cultural Heritage Agency

The earliest specimen of Auricular design may be the coat of arms of the city of Haarlem, which was made for the Meat Hall, a building designed by Lieven de Key in 1602-03. The building is regarded as one of the best examples of architecture with strapwork, but the coat of arms has a soft surrounding, which is considered to be the first piece of Auricular ornament in stone in the Netherlands [17].

Haarlem was the city where Hendrick Goltzius lived, and it is very tempting to credit him with the design of this coat of arms, which must have been executed by a skilled sculptor. Goltzius and the architect and sculptor Hendrick de Keyser (1565-1621) cooperated in 1604 on the so-called Saint Martin’s cup for the Haarlem Brewer’s Guild (1604); they were good friends and must have discussed their views on art [18].

Figure 19: Jonas Suyderhoef after Thomas de Keyser, Portrait of Hendrick de Keyser, 1621. Photo: Rijksmuseum

Goltzius, this versatile artist who was already designing prints with Auricular ornament in the 1590s, almost certainly influenced De Keyser. In the latter’s work, Auricular ornament can be found from 1606 onwards. As a sculptor he also worked with bronze, which might explain his early use of Auricular ornament and its subsequent transference to stone. Interestingly enough, he was born and educated in Utrecht, the centre of the Auricular style in the Netherlands. As a result of the friendship between Goltzius and De Keyser it is hardly surprising either that Auricular ornament found its way to architecture and the decorative arts in Amsterdam. Hendrick de Keyser used it in his architecture, as did his sons and son-in-law in the second, third and fourth decades of the 17th century.

Figure 20: Hendrick de Keyser, bust of a unknown man, 1606. Photo: Rijksmuseum

A very early work in which the influence of Auricular ornament can be found is the bust of an unknown man (dated 1606; Rijksmuseum). Note especially the wooden pedestal with its cartouche, as well as the lower part of the bust itself.

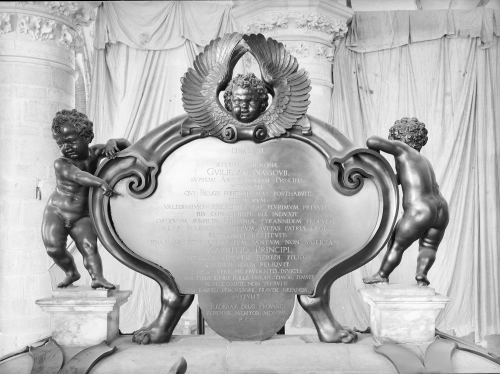

Figure 21: Hendrick de Keyser, Sign on top of the Mausoleum for William the Silent in Delft, 1614-23. Photo: Dutch Cultural Heritage Agency

Another work which shows Auricular ornament at its best is the mausoleum for William the Silent in the New Church in Delft, which De Keyser designed in 1614 and which was finished after his death by his son Pieter (1623). Both the bronze elements and especially the sign on top of the structure may be described as Auricular [19].

Conclusion

The friendship between Hendrick Goltzius and De Keyser may have led to the introduction of Auricular ornament into the field of sculpture and architecture. De Keyser transferred Goltzius’s works on paper to stone and bronze. This resulted in the use of cartouches all through the 17th century, which can be called Auricular as long as one takes the more international point of view. By incorporating the Italian, German and French traditions and ideas on Auricular style, one can see a continuous use of Auricular ornament in Dutch art and architecture.

A short excursion to Auricular ornament in churches: pulpits and tombstones

Choir screen, Nieuwe Kerk, Amsterdam, detail. Photo: groenling

The Auricular style seems to have been very popular in churches. The most famous example is the magnificent choir screen of the Nieuwe Kerk in Amsterdam, dating to c.1650 – a combination of classicisizing architecture with fillings of metalwork in Auricular style by Johannes Lutma. We know that this screen was made after the fire of 11th January 1645, which destroyed the main roof of the church. It was probably made during the same campaign as the monumental pulpit (1647-49) by Albert Jansz Vinckenbrinck (1605-1664), which also combines classical and Auricular ornament.

Figure 22: Nijmegen, St Steven’s Church, pulpit by Joost Jacobsz. Photo: Dutch Cultural Heritage Agency

It is one of at least eighteen pulpits in Holland which have Auricular ornament. In some cases they are documented, giving us dates of fabrication as well as names of makers. The earliest example is to be found in the Church of St. Steven in Nijmegen; the Amsterdam joiner Joost Jacobsz was responsible for its design and execution [20].

The ornaments are not taken from prints by Lutma, Van Vianen or Van den Eeckhout, but show a similarity to those by Lucas Kilian and especially Michel le Blon. This goes for both the infill of the panels and the cartouches on the lower part of the pulpit, which are very similar to Le Blon’s Verscheyden Wapen-schilden verciert met helm en lof [21]. The same goes for the pulpit of the Oude Kerk in Amsterdam, which was made by the joiner Jan Pietersz in 1642. Its brass banister was made by Joost Gerrits and executed in the so-called pea-pod style [22].

When looking for pulpits influenced by the prints by Van den Eeckhout and Van Vianen, we have to go to a later date. In 1656 Engel Westerwout designed the pulpit of the Nieuwe Kerk in The Hague. The pulpit with its fenced-off baptismal garden (an area around the pulpit where baptisms took place) reveal Auricular ornament in almost all its elements: banisters, friezes, panels, as well as the rounded base of the pulpit itself [23]. The same can be said of the work of Henrick Widtfelt, who was responsible for three – and possibly four – pulpits in the province of Gueldern. In 1657 he executed the pulpit for the Catholic Church in Zevenaar, dedicated to St Andrew, adorned with statuettes of the Holy Virgin and other saints. Auricular ornament was used in areas of secondary importance, such as the sides and the stairs [24]. The pulpit was generally admired in this small town, as appears from the fact that the Protestants asked the same Henrick Widtfelt to make a pulpit for their church (1659). Instead of statuettes, Auricular cartouches were applied. Widtfelt agreed to make the pulpit for 400 guilders and one ‘rosenobel’ (11 guilders); the work was to be delivered within ten weeks and would be modelled on the ‘old church’ in Arnhem [25]. This old church can be identified as the main Protestant church in Arnhem; it was originally dedicated to St Eusebius when it was built as a Catholic church. The similarity between the two pulpits is indeed striking [26]. Another (undated) pulpit which may have been made by Widtfelt stands in the Reformed church Doesburg, formerly dedicated to St Martin [27].

Apart from these examples, other dated pulpits can be found in the Protestant churches in Bolsward (1662, made by J. Kinnema), Batenburg (1665) and Leersum (1676), while undated ones can be found in churches of Appingedam, Boer, Grave, Grootebroek, Landsmeer, Maasbommel, Zuiderwoude, Zuidhorn en Zutphen [28]. The influence of prints by Van den Eeckhout, Van Vianen and Lutma is more obvious in the pulpits which are situated in or around Amsterdam and The Hague from 1650 onwards, as well as in the works by Henrick Widtfelt. In other pulpits, Lucas Kilian’s prints have had more influence, as well as in the early pulpits in Amsterdam or made by Amsterdam joiners. Except for one, all pulpits were made for Protestant churches.

Figure 23: Amsterdam, Old Church, tombstone for the De Graeff family, 1638. Photo: the author

Auricular elements inspired by Van den Eeckhout’s, Lutma’s and Van Vianen’s engraved ornamental prints are to be found quite regularly on tombstones. The earliest examples seem to date from the 1630s, even though one has to be careful with these dates; it is not always true that burial dates give the correct date for a tombstone. Probably one of the earliest examples of a tombstone in the Auricular style can be found in the Old Church in Amsterdam, made for the De Graeff family, one of the most powerful dynasties in the Golden Age of the Dutch Republic. They owned a grave in the choir of the church, where they buried mayor Dirck Jansz de Graeff in 1638. Possibly the tombstone was made at the same time; from 1648 onwards the family buried their members in their newly-acquired chapel, for which the sculptor Artus Quellinus made a screen in marble [29]. 1638 is very early, considering that all ‘classical Auricular’ prints were made more than a decade later, but we have to bear in mind that the De Graeff family kept in close contact with Johannes Lutma, who made (a.o.) a ceremonial silver trowel in Auricular style which was used by the son of Cornelis de Graeff in 1648, when laying the first stone for the Amsterdam Town Hall. In other parts of the Netherlands we find also tombstones which seem to have been made earlier than the prints [30].

Figure 24: Jacob Lutma naar Johannes Lutma, Verscheide Snakerijen dienstich voor Goutsmits, Beelthouwers, Steenhouwers en alle die de Const beminnen, Amsterdam 1654. Photo: Rijksmuseum

***********************************************

Dr Pieter Vlaardingerbroek is an architectural historian, working at the Heritage Office of the City of Amsterdam and as an assistant professor at Utrecht University. In 2011, he published his Ph.D. research on the Amsterdam Town Hall. In 2013, he wrote and edited books about the Portuguese Synagogue in Amsterdam, the architect Adriaan Dortsman (1635-1682) and the Amsterdam Canals.

***********************************************

[1] Pieter J.J. van Thiel, C.J. de Bruyn Kops, Framing in the Golden Age. Picture and Frame in 17th-Century Holland, Amsterdam/Zwolle 1995, p. 210, 212.

[2] Wouter Th. Kloek, ‘Northern Netherlandish Art 1580-1620’, Dawn of the Golden Age. Northern Netherlandish Art 1580-1620, Amsterdam/Zwolle [1993], p. 15-111, citation from p. 54. The same opinion is expressed by Reinier Baarsen, Dutch Furniture 1600-1800, Amsterdam/Zwolle 1993, p. 34, 40.

[3] Peter Thornton, Form and Decoration. Innovation in the Decorative Arts 1470-1870, London 1998, p. 96.

[4] Van Thiel/De Bruyn Kops 1995 (note 1), p. 210.

[5] J.R. ter Molen, ‘Auriculaire’, in: A. Gruber (ed.), L’Art Decoratif en Europe. Classique et Baroque, 3 vols, Paris 1992, vol. 2, p. 27-91; J.R. ter Molen, Van Vianen. Een Utrechtse familie van zilversmeden met een internationale faam, 2. vols, diss. Leiden 1984, vol. 1, p. 59.

[6] De Jonge saw Auricular art depicted in works by Jan Steen and H. van der Mijn; she dated tables and furniture with Auricular all around 1660-1680; C.H. de Jonge, ‘Ornament en meubelen in de tweede helft der zeventiende eeuw’, Oude Kunst, 1 (1915), p. 3-7. Interestingly enough, she mentions a tester bed, being modelled by the sculptor Rombout Verhulst, by which she seems to indicate that sculptors had an important hand in creating furniture in Auricular style. See also C.H. de Jonge, W. Vogelsangh, Holländische Möbel und Raumkunst 1650-1780, The Hague 1922.

[7] Zülch elaborated on Carl Neumann’s book on Rembrandt, who typified the style as ‘unfőrmig’ and saw many examples of auricular style in Rembrandt’s paintings of the 1630s.W.R. Zülch, Entstehung des Ohrmuschelstiles, Heidelberg 1932; C. Neumann, Rembrandt, 2 vols, Munich 1922 (Heidelberg 19011), p. 758-782 (Rembrandt und der sogenannte Ohrmuschelstil).

[8] Th.H. Lunsingh Scheurleer, ‘Inleiding’, in: Catalogus van meubelen en betimmeringen, Amsterdam 1952, p. 13-78, in particular p. 55. More explicitly Van haardvuur tot beeldscherm. Vijf eeuwen interieur- en meubelkunst in Nederland, Leiden 1961, p. 61-62.

[9] Willem van der Pluym, Vijf eeuwen binnenhuis en meubels in Nederland 1450-1950, Amsterdam 1954, p. 46, 73.

[10] Antje-Maria von Graevenitz, Das niederländische Ohrmuschel-Ornament. Phänomen und Entwicklung dargestellt an den Werken und Entwürfen der Goldschmiedefamilien van Vianen und Lutma, diss. München 1973, Bamberg 1973, p. 57.

[11] Peter Thornton, Form and Decoration. Innovation in the Decorative Arts 1470-1870, London 1998. He described the prints of Daniel Rabel in his chapter on Amsterdam and Auricular art saying that Rabel ‘produced a book of cartouches with Auricular features’. The image however is depicted in his chapter on Rome and Bologna, and Thornton characterizes it over there as ‘highly grotesque’.

[12] Peter Fuhring, Ornament Prints in the Rijksmuseum II. The Seventeenth Century, 3 vols., Rotterdam 2004.

[13] C. Willemijn Fock, ´Leidse beeldsnijders en hun beeldsnijwerk in het interieur´, in: Th.H. Lunsingh Scheurleer, C. Willemijn Fock, A.J. van Dissel, Het Rapenburg. Geschiedenis van een Leidse gracht. Deel IVa: Leeuwenhorst, Leiden 1989, p. 7-78, esp. 17.

[14] Information kindly supplied by Albert Reinstra.

[15] Ter Molen 1992 (note 5), vol. 2, p. 48, 82.

[16] Pieter Vlaardingerbroek (ed.), The Amsterdam Canals: World Heritage, Amsterdam 2016, p. 68, 71.

[17] Von Graevenitz 1973 (note 10), p. 54-55.

[18] L.W. Nichols, ´Hendrick Goltzius – documents and printed literature concerning his life´, Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek, 42-43 (1991/1992), p. 77-120. Nichols refers to Salomon de Bray, Architectura Moderna ofte Bouwinge van onsen tijt, Amsterdam (published by Cornelis Danckerts van Sevenhoven) 1631, p. 7; Huigen Leeflang, Ger Luijten e.a., Hendrick Goltzius. Tekeningen, prenten en schilderijen, Zwolle/Amsterdam etc. 2003, p. 28-29 and 20, note 54.

[19] For the monument itself, see Nicole Ex and Frits Scholten, De Prins en De Keyser. Restauratie en geschiedenis van het grafmonument voor Willem van Oranje, Bussum 2001.

[20] The same Joost Jacobs was also responsible for the design of the ‘Herenbank’, the benches for the city’s ruling class (1644). Here we find panels influenced by the prints of Lucas Kilian and Christoph Jamnitzer.

[21] Cf. Peter Fuhring, Ornament Prints in the Rijksmuseum II. The Seventeenth Century, 3 vols., Rotterdam 2004, vol. 1, no. 1344.

[22] H. Janse, De Oude Kerk te Amsterdam. Bouwgeschiedenis en restauratie, Zeist/Zwolle 2004, p. 325. Joost Gerrits produced some wonderful brass works in auricular style which were a gift to the Shogun and are now in the sanctuary in Nikko (Japan). Joost Gerrits was born around 1598 in the Bijlmermeer and became citizen of Amsterdam in 1641. He also made a brass candle-arm for the pulpit in Nijmegen in 1640.

[23] Cf. A. Landheer-Roelants (ed.), Uit Padmoes verrezen. De Nieuwe Kerk in Den Haag, Utrecht 2011.

[24] E.H. ter Kuile, De Nederlandse monumenten van geschiedenis en kunst: deel III: de provincie Gelderland, tweede stuk: het kwartier van Zutfen, Den Haag 1958, p. 186.

[25] For the full text of the contract, see F.A. Hoefer, “Nederlandsche Meubelen”, Bulletin Nederlandschen Oudheidkundigen Bond, 8 (1907), p. 148-149.

[26] There seems to be no archival record about the work of Henrick Widtfelt for this church; cf A.G. Schulte (ed.), De Grote of Eusebiuskerk te Arnhem. IJkpunt van de stad, Utrecht 1994.

[27] Ter Molen 1992 (note 5), vol.2, p. 78.

[28] The images of these pulpits can be found on the website of the Dutch Cultural Heritage Agency: Bolsward; Batenburg; Leersum. The undated pulpits: Appingedam; Boer; Grave; Landsmeer (with thanks to Albert Reinstra); Zuiderwoude; Zuidhorn and Zutphen.

[29] Janse 2004 (note 22), p. 261, 348.

[30] See the tombstone in Hogebeimtum, made for Focko van Aysma, who died in 1651.