Art In Conversation

ALEXANDER S. C. ROWER with Joost Elffers

Alexander Calder: The Great Discovery at the Gemeentemuseum Den Haag (February 11 – May 28, 2012), the artist’s first retrospective to be held in the Netherlands since 1969, begins with Calder’s radical wire sculptures, before examining his legendary meeting with Mondrian at the painter’s studio in Paris in October 1930 and subsequent shift to abstraction. Calder Foundation President Alexander S.C. Rower made a presentation about Calder’s artistic development to a public audience before sitting down with publisher and designer Joost Elffers to talk about the aesthetic relationship between the two modern masters.

Joost Elffers: As a Dutchman, living already for 32 years in New York (half my life), I feel my Dutch identity in a very intense way. And one of the building blocks of my Dutch identity is Piet Mondriaan (double “a”). Sandy says, “Mon-dree-on” in a French accent; in New York they say “Mon-dree-an.” Nay! “Piet Mondriaan!” At our breakfast table, with my wife, the painter Pat Steir, I teach the pronunciation of Dutch artists’ names. “Rembrandt van Rijn, Vincent van Hoh [Gogh], Piet Mondriaan!” It’s very important to me because Mondrian is one of the building blocks of my being. When I was asked to speak with my friend Sandy about Mondrian and Calder here, I said, “But I am not an art historian, I can’t say anything. I have no basis for that.” But then, over the weeks before coming, it occurred to me that I had a lot to say about his work. I started to read Hans Janssen’s great book, The Story of De Stijl: Mondrian to Van Doesburg, about the relationship between Mondrian and De Stijl, which also points out the difference in their birth dates. I realized that Mondrian was born in 1872, almost a generation earlier than van Doesburg (1883). That means Mondrian was 28 years old in 1900. Why is that so important? Because at the first De Stijl exhibit that I saw in 1983 in the Kröller-Müller Museum, I was stunned by the difference in quality between Mondrian and the rest of the De Stijl group.

Alexander “Sandy” S. C. Rower: Because of Mondrian’s maturity?

Elffers: Yes, also because Mondrian is absolutely pure. His quest for not only excellence, but for the divine, is absolute. Absolute!

Rower: Divine, like, spirituality?

Elffers: Yes.

Rower: No, Dutch people do not think Mondrian is spiritual.

Elffers: True, but he was born in 1872, which made him a man from the 19th century. And there he was as a young man table dancing with Annie Besant at the Theosophical Society, of which he became an active member in 1909. For a long time, the Dutch art historians had enormous problems with the influence of spiritual and mystical sources, as they had rejected their Protestant upbringing in favor of atheistic Modernism. By 1914, when he found abstraction—for example, in his series Pier and Ocean—he had moved beyond not only his previous rapport with 19th century mystical theosophy, but also Cubism. In 1980, I co-created a book on Rudolf Steiner architecture called Rudolf Steiner und seine Architektur (DuMont), and I spent a few weeks in Dornach, where it became clear to me that Mondrian must have been inspired by the thinking, but not the art, of Steiner. One thing that we can all agree on is that Mondrian, through the language of spirituality, gradually discovered his own original language. Now, Mondrian and Calder met in?

Rower: October 1930.

Elffers: At Mondrian’s studio in Paris. It immediately strikes us as an unlikely friendship because one is a spiritual high priest of abstract art, while the other is a playful, open-minded sort of artist, but as Sandy said earlier, “Mondrian liked to dance. So did Calder.” But Mondrian danced like an autistic nerd [laughs]. In other words, “He danced geometrically”; quite the opposite, Calder could dance naturally, like Sandy’s mother, who would dance before or after a great meal she cooked. Mondrian had not that chance. Mondrian, in his studio, would sleep alone in this little bed, and he had a photograph of Josephine Baker hung above his head. And he probably still had trouble keeping his hands above his blanket—because that is what his Protestant mother said to do [Laughs].

Rower: [feigning shock] Oh my goodness.

Elffers: So the two dancers are so far apart, and yet so close to one another. One last thing I would really like to say about Mondrian’s interest in the mystical part of the late 19th century was that he understood Annie Besant and the aspiration behind theosophy as a movement as means by which to seek meditational models in abstract art. And the art should be made for meditational purposes with natural techniques, such as using sunlight, but it should not be painted by the hand. The hand is the tool, but the direct source of the image is generated from random processes. This method of meditating on an abstract plane manifested itself in the Rorschachtest in 1921. And the Rorschach test is really a mirror to reflect the unconscious of the test subject. My friend Mark Mitton said, “But it was even four centuries earlier that the mystic, in England, John Dee (1527 – 1608/9) had a polished black stone on whose surface people would meditate and see angels.” Similarly, the Rorschach test is still not an objective tool, as people see what the time dictates. So the inspirational sources for the mystical influences of theosophy on Mondrian were not only kitschy religious beliefs, but also meditational abstraction.

I have a big question for Sandy now. When I first met his family, they were all down on Picasso; “How is that possible?” I asked. They replied, “Because there are so many dark elements.” “Art,” Sandy’s mother said, “was about happiness and engaging the world.” And my painter wife said, “Yes, it is easier to make a difficult painting than a happy painting.” It is very hard for folks from Calvinist culture to accept happy art as serious. The Sufi stories come to mind, where you don’t know who the master is—it can be the servant, it can be the man who is always smiling, or somebody else. So I think the genius of Calder is that he made masterpieces that were happy. And that is rare in art history.

Rower: I agree. I grew up hating the word “play.” People always talk about Calder as being an artist of “play” and “joy.” And I remember in the ’60s and ’70s my grandfather was dismissed as a “playboy” and not as a rigorous intellectual. I began our family foundation in 1987, partly due to the fact that I was very frustrated with those misreadings. We tend to forget that in 1931, for example, Fernand Léger wrote an introduction to a catalogue of a Calder exhibition—the first exhibition of Calder’s abstract works—and he compared Calder to Erik Satie and Marcel Duchamp. By 1971, no one mentioned Calder in reference to those other intellectual luminaries. It was a great sadness of mine growing up that people just saw “color, form, and motion.” If you understand Calder as color, form, and motion, you do not understand Calder. And so “play” was a great four-letter word in my family—anytime someone wrote or said “play” in relation to Calder, it was very objectionable.

We did a symposium a couple years ago at the University of Virginia, featuring scientists of different fields. There was a mechanical engineer, an astronomer, a physicist, and so on, and each of them presented their ideas as related to Calder in their own particular discipline. They were all connected to Calder because Calder is about energy. And one of the scientists started talking about play, and I became very annoyed at this concept of “play, play, play, play.” Then he said, “Play equals innovation.” And I realized that his definition of play starkly contrasted with the dismissive sense of “we don’t need to look at Calder because he is not serious.” It was so remarkable—it reminded me of the feminists who appropriated words that were intensely offensive, taking possession of them to own and use them as part of their political language. This led me to realize that I similarly have the opportunity to take the word “play” and make it my own, and then present “play” as Calder’s innovation, and present it where Calder’s genius lies.

In talking to you, I realized that my own sense of Mondrian was different growing up than most of the people around me who thought that Mondrian’s rigid “geometry” was this rational, possessive, slightly bizarre—autistic was a good word—representation of a theory, not realizing that, in fact, Mondrian’s work is deeply emotional. His retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in 1995 revealed his re-correction of lines in his drawings and the analysis of paintings showing how lines have been moved even a half-millimeter this way or that way and painted again and again in order to find the perfect harmonic definition of visual existence. Something entirely different from “X times 2 equals 3N5,” therefore put a line here and so forth. When Yves Saint Laurent emulated Mondrian’s geometry while dismissing its underlying emotional aspects by putting it on a dress, I remember, as a kid, being so repulsed by it.

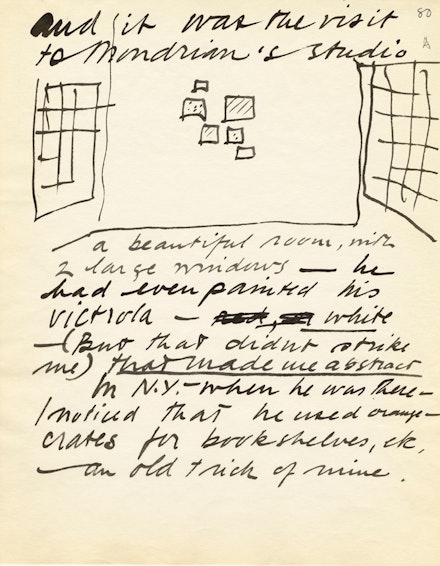

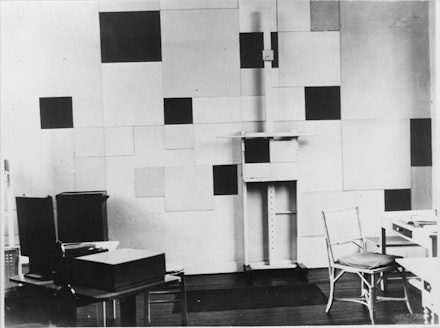

We had a great talk this morning with the architect who recreated Mondrian’s studio and installed it in the exhibition. And having known my grandfather very well, I have a sense of what it was like for Calder to walk in and see some colored rectangles on a wall and these two cubic spaces—it was almost a visceral thing. Mondrian’s studio had five walls, one being at the intersection of two cubic spaces. What was Mondrian’s solution to this terrible problem of how to make paintings with four corners in a room that has five corners? He defined a four-cornered space that intersected another four-cornered space.

Elffers: But then you step into this replica of Mondrian’s studio, here in the exhibit, and you can imagine how his painting got made in this specific space and how his dreaming of the paintings going out to the world got materialized. He probably knew they were made for the future. It’s really an amazing thing.

Rower: The idea of reconstructing a studio, of course, poses a real challenge to all of us at the Calder Foundation because we still possess Calder’s studio of 1938; the actual building, the actual tools, the actual materials on the floor all exist as he left it. And we have the struggle of what precisely to do with it. How do we present that? With Brancusi, they took his studio apart and transported it. Renzo Piano made a building just outside of the Centre Pompidou, and they tried to replicate the sensation you would have had as you walked around the exterior, looking through the walls into Brancusi’s studio. It’s a very difficult subject—how do you present the artist’s space? How do you give public access to hundreds of thousands of people who want to come to see the space yet retain its feeling of a private space? Seeing this recreation of Mondrian’s studio, and other examples around the world, both good and bad, is very helpful to us.

Elffers: And no matter how truthful or not to the original space the reconstruction is, it still inspires us. Currently the Gemeentemuseum is showing 17th and 18th century scale architectural models, which are delightful. Everyone is drawn to dollhouses from when they are children. We should not, out of puritanical perfection, deny the audience that pleasure.

Question #1 (from the audience): Do you consider Calder to have been a mystic?

Rower: My grandfather was a devoutly non-religious, spiritual person. In terms of being a mystic, absolutely yes and no. He was able to tap into something that had not been expressed before. His sculptures are made out of metal and yet they are incredibly ephemeral. His mobiles, which are made of sheet metal, wire, and paint, exist in space, yet it is their immateriality that makes them unexpectedly relevant to contemporary art. The genius of Calder lies at the intersection of the mobile element and the air. As the sculpture moves through space, the composition changes, as does the viewer’s personal experience in real time. The line created between the material and the immaterial is Calder’s genius. Is that mystical? I don’t know. Let’s put it this way. André Breton included Calder’s work in many of his exhibitions of Surrealism, but Calder never considered himself a Surrealist. His dealer, Pierre Matisse—Henri Matisse’s son was Calder’s dealer for about 10 years in New York—listed on top of the gallery’s stationery: “Modern Paintings, Primitive Sculptures and Ancient Art of the Americas”—and Calder asked him, “Which one am I?”

Question #2: Could you elaborate further on what you meant earlier in your presentation when you referred to the “line of energy” in his mobiles?

Rower: My grandfather preconceived the fourth dimension in his head as a child. So by the time he was up and running as an artist, he was describing the eighth and ninth dimensions. Now we talk about the 13th dimension, string theory, the unifying force. Calder was trying to describe something intuitively—through his own process—about these energetic forces. In 1931, he made abstract sculpture about a non-scientific description of energy, and by 1934, in order to try to understand Calder, people wrote: he is describing “the universe”—the sun, the moon, the earth, orbiting bodies—that’s the best that people could understand what he was trying to describe. But he wasn’t describing the universe, he was describing a universe. He was describing Calder’s universe, which was an attempt to bring together all these different harmonics of energy, of experience. He was very interested in things beyond the five senses. He was not a mystic, but I would say he was mystical.

Question #3: In your presentation you showed us Calder’s “Hercules and the Lion” (1928), and I immediately thought about the paintings of Picasso, who had the same classical ideas of drawing in the ’20s. Has there been any connection, any relation, between Picasso and your grandfather?

Rower: Some people have written about Picasso and Calder. Picasso made his model for a monument to Apollinaire in 1928, after Calder had been defining volumes in space with wire for some years. Calder never saw Picasso’s early sketches for this monument, which didn’t get made as an enlarged version until 1962. But Picasso did see Calder’s exhibitions in Paris. Certainly there are similar effects, but there’s no specific art dialogue or specific discussion between them.

Arp, Kandinsky, and Klee all had more influence on Calder than Picasso. But one of the most pronounced connections between one artist and another is Miró and Calder: how Miró influenced Calder, and Calder influenced Miró, and the fact that they had a considerable parallel resonance, both having come from Arp and Kandinsky and Klee and so forth. Miró’s grandson, who is a dear friend of mine, wrote an essay debunking this notion of influence between Miró and Calder and presenting this sort of resonance back and forth throughout their careers and lives with thoughtful details and insightful observations.

But back to your question, there is no specific relationship with Picasso. The great thing about this exhibition is that they have tried to reconstruct an experience that occurred in October 1930. How accurate is it? The representation of the studio in the exhibition is Mondrian’s studio of 1926. Calder arrived in that space in October 1930, four years later, so it’s not precisely what Calder saw. The back wall, the largest wall in the studio, is the wall that Calder saw—the colored rectangles, with cross light. And those colored rectangles on the wall could be repositioned for compositional experiments by Mondrian. Calder describes 1930, but we are seeing 1926, so it’s a little bit of a challenge. It’s much harder to reconstruct the studio of 1930, mostly because there isn’t as much documentation as of the studio in 1926.

Question #4: Are there sources that indicate that mobiles were made before Calder’s?

Rower: Sure, you can go back to China, a couple thousand years ago, and find that there were objects made that responded to wind and made pleasant sounds. They were the earliest forms of chimes, you may say. And as early as 1920, Man Ray made a pyramid of coat hangers, each with two more hangers suspended from its ends, which continued in arithmetic progression until almost the whole room was obstructed. After all, the title of the piece is “Obstruction,” but it was really unrelated to mobiles and had a functional purpose. Naum Gabo made a few suspended plexiglass objects that could rotate, with all of their complex intersections, including the ones with wires that generate volume, but they’re very static except this subtle rotation quality.

Question #5: If my recollection is right, in March 1977 I flew from New York to Buenos Aires in a plane painted by your grandfather. Can you confirm whether he painted it? And how did it come about?

Rower: I’m glad you brought that up. Braniff International Airways was once a small, aggressive airline; I would say the equivalent of Virgin Atlantic Airways (which started in 1982, the very year that Braniff International Airways closed). They were full of new ideas and so on, and they had this advertising agency in New York to come up with ideas to bring attention to their aircraft. So they sent this PR fellow from New York to meet my grandfather in France, and he had no idea what he was going to ask Calder, but while he was in the airport he bought a plastic model of a 747. Well, given the fact that by this time Salvador Dalí was famous for being on television selling toothpaste—essentially, it was a time when artists were considered celebrities, and they did all sorts of commercially: related things—he came up with this idea of inviting Calder to paint the plane as “his biggest mobile.” Calder liked the idea of decorating an airplane because he thought it was quite a challenge, but my grandmother was absolutely against the idea and thought it was undignified. Keep in mind, she was a proper Bostonian, who was the great-niece of Henry James and became a bohemian because of her husband. In any case, after some thoughts and conversations, she decided not to intervene and to just let him try it out, which he did. He ended up painting three different plane schemes for Braniff. The first one’s the best and probably the one you were on—it was very colorful. The second one was the “Flying Colors of the United States” for the Bicentennial in 1976, which was the year that he died. He made a third design that was never realized, but which was finalized by the time he died.

Elffers: And his wife hated the second one even more!

Rower: Yes, because they were very much against the Vietnam War. My grandmother was really politically very active and very vocal, so the idea of this patriotic project—red, white, and blue on planes—was even more disgusting than the first one. The guys at BMW saw his first plane and thought, “Oh my God, we have to have him paint a car, that would be so exciting.” So he painted a car in 1975 and it was sort of in secret because he felt a bit like he was betraying the airplane project. And that was the beginning of their whole Art Car series. Now BMW has this tradition of having important artists paint their cars.