Art In Conversation

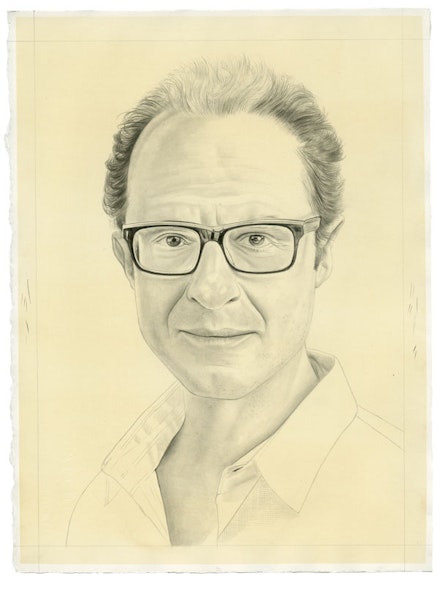

WAYNE KOESTENBAUM with Phillip Griffith

On September 21st at The Kitchen, Wayne Koestenbaum performed a suite of trance-like Sprechstimme improvisations at the piano to mark the publication of his new book, The Pink Trance Notebooks, a series of poems assembled from a yearlong experiment in journaling (Nightboat, 2015). In the most rousing of these songs, Koestenbaum intoned praise for having his tubes tied at Duane Reade—all set to a piece by Chopin. The week before this performance, Koestenbaum, whose seventeen other books include volumes of criticism, poetry, and a novel, sat down with Phillip Griffith in his Chelsea studio to discuss poetry and painting, trance, the French language, and “fag ideation.”

Phillip Griffith (Rail): I thought we’d start with the titles of these poems. You title each poem Trance Notebook, give each a number in the series, and then another title in brackets. You pluck that bracketed title from one of the fragments that make up the poem. How did you make the decisions for those titles? Did it have to do with how you composed the poems?

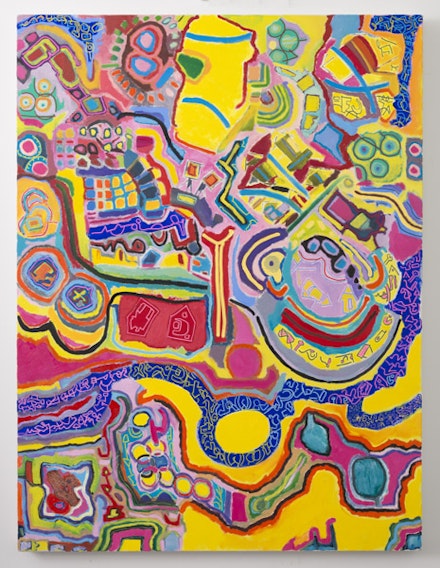

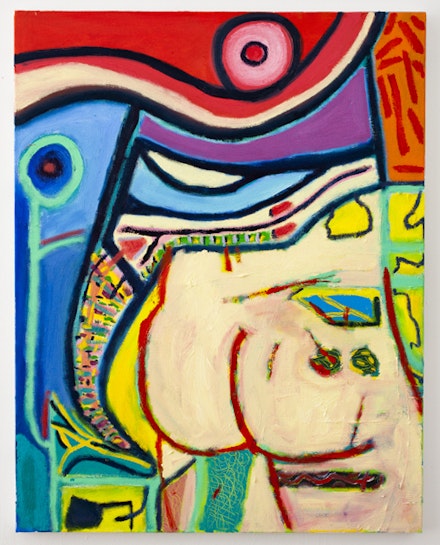

Wayne Koestenbaum: The decision-making process was similar to most of the titling I do. The title comes after, from scanning the section and trying to choose something that sounds nice by itself, and that seems symbolic or allegorical enough that it opens out toward something else. Sometimes, as with my book Blue Stranger with Mosaic Background, that phrase doesn’t appear in the book at all, but the painting I chose for the cover is called Blue Stranger with Mosaic Background. As for the Trance Notebooks’s bracketed subtitles, I simply chose a phrase that seemed allegorical.

Rail: So some of these fragments can stand for the whole? So many of them could be allegorical in that way. Are the fragments equal parts? Or are there moments that somehow rise above the rest?

Koestenbaum: Some of the fragments fall into a kind of narrative, with thematic sequence, either syntactically continuous with the ones that came before, or using verbal repetition, a kind of litany. At the end of one of the early notebooks I mention a dog, and the dog continues for two pages, which is an unusual continuity. In other cases the fragments are freestanding. And sometimes freestanding doesn’t mean allegorical or above the fray. Sometimes the phrase is just an aside or—not quite a punctum, but maybe a punctum to the extent that a punctum includes the accidental, the extraneous.

Rail: Did you write these poems in a trance?

Koestenbaum: It would be lovely to invent a whole fiction that I could spin via the Brooklyn Rail. When I speak to the newspaper of record, what account shall I give of my composition? The word “trance” came to me before I wrote most of what became the The Pink Trance Notebooks. When I set out that very first day, beginning them, I didn’t say, “Now I’m going to do trance notebooks.” But it came to me pretty quickly that I would be operating in these notebooks with an unusual lack of premeditation, lack of intention—and a corresponding abundance of physical freedom of movement. The notebooks were handwritten, and written as quickly as I could. What made the process trance-like was that in the drafts of the raw material, there’s really no punctuation except for commas. There’s not much punctuation in the final version, either, but in the original drafts, there were no interruptions, no pauses, nothing stanzaic in the least. It was pure torrent. I used small Moleskine notebooks and I’d write somewhat large, so there would be about five words per line. I used that line length as a kind of arbitrary measure, as a visual measure rather than a sonic or syllabic one. The process was trance-like because I often didn’t know what I was thinking, saying, or doing. And, since I spent so much time drawing and painting, I tried to find a way to make handwriting as much of a sport as possible. I tried to reinvent my handwriting. I tried to reinvent my arm and shoulder position, to think about how I could write so that it would physically feel like sketching—lines, or semantic lines in poetry, with abstract or other kinds of graphic lines.

Rail: You’ve called these poems assemblages. Thinking in relation to the visual and the plastic, there’s the idea of sculpture behind that word, as well. Is that part of this physical activity of being in your arm while you’re writing?

Koestenbaum: I think it’s more the assemblage…

Rail: [Laughs] With a French accent.

Koestenbaum: I thought of it as different than collage. I was happy with the word assemblage because it reminded me of Robert Rauschenberg. I don’t know if he used the word—he used “combines” to describe his sculptures from the ’50s. I think of collage as very writerly and two-dimensional, and I think of assemblage as hyper-conscious and controlled and devoted to excisions rather than random inclusions. Assemblage is more three-dimensional and more hieratic than collage. Collage implies an artifact on the page, a flat surface with which a reader/viewer has a one-to-one relationship, while assemblage is a little more aloof. I wanted to emphasize with the word assemblage how much I literally assembled the fragments from a heap of raw materials; the lines are sometimes exactly as I originally wrote them, but most often I’ve altered them, moved them out of their original sequence. Originally they were not in stanzas; they were not fragments, they were flow. Revision was a matter of taking a clump of language, putting a horizontal dividing-line below it to demarcate it from its neighbor, and then taking another clump, like a flower arranger: “Put this here, put that there.” As if from above and partially.

Rail: The way you’ve just described excision and placing clumps makes me think of Robert Smithson’s Heap of Language, which is a drawing in language, but it’s also moving towards his kind of sculpture.

Koestenbaum: Maybe John Chamberlain’s wrecked cars are more what I was thinking of, particularly because of a show I once saw at Cheim & Read with Joan Mitchell and John Chamberlain’s work together. My pink trance originates from a very New York School/Joan Mitchell movement of thought. And even the kinds of collages that James Schuyler did in something like The Fauré Ballade, or in John Ashbery and Joe Brainard’s The Vermont Notebook, or Schuyler’s The Home Book, combined with a more “masculine” form of assemblage like in John Chamberlain’s work.

One more thing I wanted to say about the visual: when I revised the poems, at least with the first go-through of the raw material, I was physically standing up. Literally on my feet. And I also used a different kind of pencil. I have these new pencils that I really like; they’re called Palomino, and they’re really soft. They have become my revision pencil because of their softness. Revising, I would stand at the kitchen counter, and I would look down at the poem, with a certain pleasant detachment. Standing, I felt like I was reaching out in space toward the things on the page, rather than sitting hunched over at the computer or typewriter.

Rail: Is that position of looking down at the poems the influence of painting? We’re in your studio, with big tables, where one can easily imagine you standing there, looking down at a visual work in progress.

Koestenbaum: Maybe it is. And I started painting at my kitchen table. In this book, there’s a greater gap between composition and revision. There always is a gap, but the gap was more extreme this time. I had no thought of a final project whatsoever when I was writing the notebooks, and I did not begin to revise any of them until the whole year had been completed and I had finished the physical longhand composition of the draft notebooks.

Rail: And was that a rule you set for yourself?

Koestenbaum: Yes. When I would finish one of the notebooks I would type it up. With the first couple I remember I made excisions, and then I thought, I don’t know yet what I want to excise so I’m just going to type up the whole thing exactly as it is, with the line breaks exactly as they fall. Correcting typos and things like that, but otherwise the rule was that I would write longhand in these notebooks with great speed and inconsequence for a year. I was thinking: rules are good, and years are good. I was enjoying the process so much, and I didn’t know what the results would be. I just knew that I was really enjoying what I was writing and that I was going places in my writing that I felt I hadn’t been in a while, or ever. I wanted to keep up the adventure without making a premature decision that I thought would be ultimately a negative one—negative meaning, oh well that didn’t work, I’ll start something else now. But I thought of Ashbery writing Flow Chart in one year. I think it was the year after his mother died, and that made an impression on me when I learned that. It’s probably my favorite of his books. So I thought of Flow Chart—that this would be my Flow Chart.

Rail: Let’s go back to what you were saying about John Chamberlain, and how he represents something more masculine, in contrast to Joan Mitchell, who also had a masculine way about her. When I think about the notion of trance, I immediately go to clairvoyance for some reason—

Koestenbaum: —Hannah!

Rail: Right, because of Hannah Weiner. It seems like trance, especially as clairvoyance, is often gendered and associated with the feminine. Is that something that you were aware of in this book?

Koestenbaum: I’m always aware of identifying with women—and with those stigmatized figures, reclaimed by feminism and other liberatory movements—figures like the witch, or the hysteric, or the crazy clairvoyant. My whole life, long before I had theory to back me up, I’ve identified with those outcasts. In the most extreme-unto-trance moments of composing, I felt like Hannah Weiner, just reading the language, the language coming to me as if written on another person’s forehead, or on an invisible chalkboard. And I let myself go further in that conviction without wishing to induce a psychotic break in myself. You know? [Laughter.] But I let myself believe that the words were externalized; after an hour of transcribing those externalized words (written in space on an imaginary chalkboard), it does begin to seem kind of true, that the words are there and I would simply write them down. Sometimes I would put them down, thinking I was done, and then more words came, and I’d have to write them down, too. That began to be addictive, that sense that the words were waiting for me to just write them down, and I would try to get into a flow state where I would just be writing again. In a kind of Artaud-like way, I would let myself write nonsense words, like spells, incantations, conglomerations of vocables. I would start writing whatever letters I wanted to write, and I would do that for a few lines and eventually, suddenly, it would turn to regular language. I was definitely influenced by Artaud, whom I adore. And Hannah Weiner, in that clairvoyant aspect of her work.

Rail: I want to ask you something more general about your poetics. It’s related to what we’ve been talking about, to this idea of assemblage again. In The Queen’s Throat, you talk about being a list-keeper, and you write that a list is “not to refine or browbeat, but to include, and to move toward a future moment when accumulation stops and the list-keeper can cull, recollect, and rest on the prior amplitude.” So is that what’s going on in The Pink Trance Notebooks? And is that what’s always going on in your poetry? Just thinking about—

Koestenbaum: —resting on prior amplitudes? [Laughs] That sounds fun.

Rail: I was looking back through Blue Stranger and even there, there are poems that seem to be lists—of couplets, or of phrases that seem like aphorism—though they’re more controlled than the work in this book.

Koestenbaum: Those poems and the poems in the book Best-Selling Jewish Porn Films right before it, were written in exactly the same way as The Pink Trance Notebooks, but for those earlier books, the trance would only go on for an hour, and it would be with an aim of producing poems. The revision process was the same as for the Trance Notebooks—excision and culling—but I was thinking in a much more constricted way of the history of modernist and post-modernist poetry, and of parataxis and juxtaposition. Rhetorical strategies that I worked way too hard trying to figure out. I don’t think it was productive, working so hard to make sure that I was in control of whatever rhetorical move was going on. Those earlier books of poetry would have been much longer and looser if I had done less of that surgery. I’ve never really let myself be as loose as I am in Pink Trance.

Rail: I appreciate both. I like the tension and torsion in Blue Stranger, between couplets or lines that don’t seem to go together.

Koestenbaum: I really thought that was the only way, and I ultimately got that from Donald Barthelme, whom I was very influenced by when I was younger and writing fiction. Or even reading Susan Sontag later in her essays and finding that the edges between fragments needed to be extremely meditated and aimed. I always felt that the only way I could get away with my paratactic digressive style was by working as hard as I could at those edges.

Rail: You mention Eileen Myles as an influence on this book, particularly in her enjambment and line breaks. She has said that a line break is all about feeling. You just do it because you feel you should. Reading her, that feels true. Was her influence there to help you get away from your own exactness?

Koestenbaum: A little bit. I know that in my poems the lines have often been end-stopped. I certainly started out as a poet writing in form, often just syllabic form. I was influenced to my detriment as a poet by people like Robert Lowell and Sylvia Plath, and others too that used these very hard lines with some relation to iambic pentameter. Ashbery has that kind of line, so do Wallace Stevens and W.H. Auden. And I really love those kinds of lines as a reader. When I think of poems, I do think of those kinds of lines. But, from William Carlos Williams and Robert Creeley through Eileen Myles and beyond, as a reader, I tend to love a different kind of music. I am less intuitive, just less good at all that than Eileen Myles, so I am aware I have certain rules about line breaks. I don’t want to paint myself in a corner of either rigidity or competence about line breaks. But I know that line breaks became easier for me in this new book because I vowed not to care about them so much. Except in the doctoring of it later to care a little bit.

Rail: Are there other ways that you see yourself as a poet in New York? Some kind of influence from or kinship with Myles might be one way, but how do you see yourself in relation to the New York School?

Koestenbaum: Before I answer that I want to say that I would be equally satisfied if this book were read as prose. Even though we’re talking about line breaks, I was aware when I was writing and assembling it that I would be just as happy to consider it a—not a memoir exactly, but an erratically laid-out book of experimental essay writing.

I don’t have the most authentic relation to New York in terms of the New York School, because even though I lived here in the ’80s, I didn’t really live here in the most organic way because I was a graduate student at Princeton. I know that, when you say you were living in New York in the ’80s, it implies being in the swim of a lot of really cool things that were going on, but I was just trying to make my way. And then, I moved back to New York in ’97. There’s something about what New York represented to, say, Eileen Myles, who was here all along, that through the obvious economic and cultural forces is definitely over, and it’s now a different place. And so we all live in the expensive wreckage of what used to be New York. But, nonetheless, I have roots here.

Rail: There is some kind of confessional impulse going on in this book.

Koestenbaum: I do love confessions. I can’t help confessing. One big difference between The Pink Trance Notebooks and earlier writing of mine would be that in earlier writing, sentences would begin with “I.” In the Trance Notebooks I don’t say “my father,” I say “father.” You know in some cases, in many cases, I mean, “my mother,” but I like just saying “mother” to slightly universalize or make it abstract. I also say somewhere, “Fathers are conceptual.” My mother is very confessional and my father is not at all. So my mother—I’ve always been quite inundated with her, with her life, her history. And my father—it’s a struggle to get anything out of him. Maybe that’s typical of fathers and mothers culturally. It’s why all fathers are conceptual. You can’t figure them out. Particularly if you’re gay. Gay male. That’s why you have to sleep with them to figure them out. That’s so ’50s to say, but it is a little bit true that I encourage in myself this strand of believing that the father is enigmatic to increase the eroticism of men for me. It’s a turn-on, basically. And I know it is, and it helps my writing, and so I try to expand the space of the conceptual father for reasons of—call it arousal and enchantment.

Rail: On the topic of a gay poetics, one of your bracketed titles in the book is “[the nearby succulence of fag ideation].” Can you say something about “fag ideation?”

Koestenbaum: I was just thinking yesterday that I wanted really badly to teach a course called “Fag Exegesis.” I obviously couldn’t use that title. So I could call it “Homosexual Exegesis.” I could do that, and that was inspired by a rereading of Boyd McDonald’s classic tome Cruising the Movies [1985]. He is like my primary influence, and he has fag ideation. I induce fag ideation to make language work for me—to induce both arousal and overelaboration—which I think of as just trying to arouse the language-making impulse in me, which I can do through excitement in some way. So I guess fag ideation is the way I choose to make my public, intellectual, and creative statements. Everything I’ve published is under the sign of some kind of reclamation and revalorization of classic styles of homosexual thinking. Modernized, brought up to date, shame more or less removed except where it’s educational to let it remain, and with the windows open a little bit. Frank O’Hara in Second Avenue, that is “fag ideation”: the density of reference, the unapologetic use of argot and other spliced idioms with no explanation but the assumption that anybody worth knowing understands this tone, this star citation, this bit of slang. And it’s a kind of take-no-prisoners, queen speed; that is the apex of poetic density, in a Mallarméan way. That’s to use Mallarmé in a pretty loose sense, but I think this “fag ideation” represents a Parnassian peak of the world as Art. The nearby succulence of it is that I need its heady proximity. I need to have the erotic cornucopia around me to feel alive, and that answers the question about why I’m in New York. I would die, drown, if I were not surrounded by a sense of erotic plenty. That’s New York.

Rail: I read another interview where you talked about introversion, and there you confessed to being an introvert. Would this book have been possible without being an introvert? Is that crucial to this writing?

Koestenbaum: Totally. I wrote, I think, a third of it in trains, and coffee shops, and subways, and doctors’ waiting rooms, waiting. I certainly would not have written the things I’ve written, or practiced the piano, or painted, or done all the things I do, if I had a natural human wish to socialize with the abundance of someone taking full advantage of living in a city like New York. I’m secretive, private, and I like to do things by myself. And, this is true of most writers or painters. I feel happiest as a human being if most of my day is spent by myself. And then I long for people.

Joyce Carol Oates has always been a kind life-model for me. She was one of the first contemporary short story writers I discovered when I started writing fiction in college. And I studied her early stories very carefully for tips on how to enter trance states. In her work, I love her immersion in these extreme forms of consciousness, kind of gothic, and erotically obsessed. I was also aware that she was famously productive and that therefore she lived in her fantasies most of the time—that seemed true of me, and I think maybe of other people who have gothic and erotically obsessed imaginations.

Rail: I wanted to ask about foreign languages. There’s German and French in the poems in this book. Specifically, there’s a passage where, at least as I read it, you’re taking French phrases and modulating the syntax or the sounds into English. What’s your relationship to those languages?

Koestenbaum: I love the French language, and I love French literature. In my not-quite-competence at French, or my not being really fluent or having done the proper things in the proper order in my life toward competence in French—like living in France, or majoring in French, or taking French in college like I should have, having a French fling—anything I could do, I’ve never done any of that. But it’s only increased for me the allure of French as the sound of all sorts of freedoms and luxuries. In the passages that you’re mentioning, those French phrases appear to me, just like, “Je peux rester ici sans angoisse,” something like that. Vague French phrases appear to me sometimes; I took German lessons for a while, but my German is much more rudimentary. I really can’t touch German. But I have tons of memorized opera phrases in my head—French, Italian, German—with a very intricate sense of what the words mean—“Sempre libera,” “Mon coeur s’ouvre à ta voix.”

Rail: They become talismanic.

Koestenbaum: Yes, and I know all the nuances of what those words when sung feel like, all of them, every bit of it. And so it occurs to me, particularly when I’m in a more trance-like state writing, when I’m just staring into space and looking for language, the French angoisse is going to come to me a lot faster than the English anguish. And it’s going to feel like anchois—anchovy—and Angus steak.