ArtSeen

Hans Holbein: Capturing Character

On View

Morgan Library and MuseumFebruary 11–May 15, 2022

New York

Renaissance portraiture has been much before the eyes of New Yorkers over the past year. As recently as October, the Metropolitan Museum was decked out with sixteenth-century Florentine portraits by the likes of Jacopo Pontormo, Agnolo Bronzino, Benvenuto Cellini, and Francesco Salviati, and now the Morgan Library and Museum is offering the first US exhibition ever devoted to their Northern contemporary, Hans Holbein the Younger, one of the greatest exponents of the genre. The Met struggled to form a coherent picture of the diverse portraits on its walls, although the attempt was uniquely thought-provoking. In contrast, the Morgan’s curators (working with their colleagues at the Getty, the show’s first venue) opted to center proceedings on a single painter. Consisting of works by or relating to Holbein, the show certainly coheres, but there’s nothing straightforward about Holbein or the remarkable things that he painted.

Having lost a lucrative business in sacred commissions with the advent of the Reformation, the German-born Holbein reinvented himself, wandering Northern Europe and plying the trade of the portraitist. Whether his sitters were famous intellectuals, wealthy burghers, or powerful princes, he found ways to represent people that resonated with how they wanted to be known, manipulating body language, clothing, and setting to reflect his sitters’ social, cultural, and political circumstances. Extending his descriptive inclinations from faces to fabrics, the resulting portraits often feature bravura displays of naturalism. Yet, Holbein also relied on words, symbols, and allegories to help build representations of the entire person. Legible words appear in books and letters on display in these paintings. And many of his portraits are superimposed with golden letters giving the sitter’s name, age, or the date of execution, certifying each as a record of a particular moment. Objects may look innocent, but they almost never are, encrypting additional layers of meaning: a bejeweled hat badge might contain an allegorical device telling us something about the wearer, just as a pet squirrel might allude to a family’s heraldic emblem. Far from being a purist, Holbein made use of any visual information at hand.

You might think that Holbein’s use of such diverse strategies of characterization would result in portraits that feel overburdened or heavy-handed, except that Holbein’s sense of the appropriate was pitch perfect. Although he sometimes idealizes, Holbein makes us forget this in his remarkably lifelike handling of strategic details. It seems only natural, for example, that the beautifully composed Sir Thomas More (ca. 1527) should also feature Holbein’s minute observation of his stubbly chin, or that the almost surreal symbolizing animals and plants in A Lady with a Squirrel and a Starling (Anne Lovell?) (ca. 1526–28) should be joined with reality through the utterly convincing portrayal of the tufted fur of Lovell’s ermine bonnet. Nor do we doubt that the handsome Simon George, who proffers a carnation with an elegant rotation of his hand, was anything but perfect-looking in life because of Holbein’s dazzling rendering of the variegated blacks of his embroidered doublet. That said, sometimes idealization is nowhere to be found. The Basel printer Johann Froben comes off as honest and forthright precisely because Holbein refuses to disguise his homeliness.

Holbein’s portraits have such aesthetic rightness about them that they convince us they are embodiments of real persons. What is more, they seem to have possessed this quality almost from the moment of conception. Often begun as chalk drawings (wonderful examples appear throughout the show), the heads and busts of sitters hover on flat tinted pages, each fitted to the paper size, supplemented by texts recording the sitter’s identity and various shorthand aid-mémoires. Although the portraits vary considerably, one can nevertheless generalize. Most sitters keep their limbs close, hands folded before them, handling an object, or writing with a pen. They do not gesture grandiloquently in the way of contemporary Italians, like Pontormo and Bronzino’s posturing persons (one grand exception is the lost, full-length Henry VIII, known from copies). The informal formality of Holbein’s presentation in these cases is captured so well that it paradoxically lends credibility to the naturalism itself. For the sitters generally appear as if seated before the artist, composing themselves according to the conventions of the portrait sitting. They themselves seem to impose the pose rather than Holbein, who then places them in their setting, whether against a monochromatic ground or in a more detailed scene. The contrast between the figure and its backdrop gives many of Holbein’s portraits their punch.

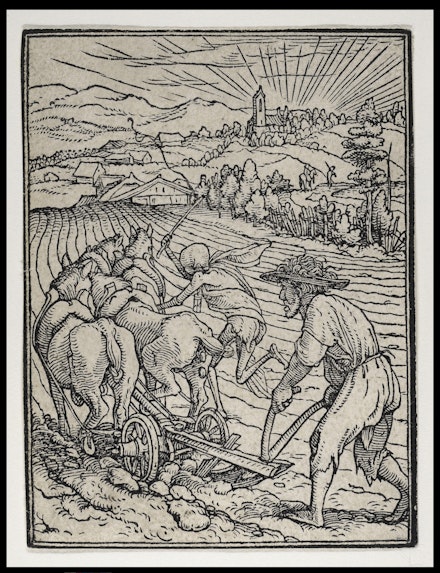

Like the Met’s show, this one spends time on the accoutrements of portrait painting. Dazzling bejeweled and enameled gold hat badges appear next to Holbein’s paper designs for lost examples. Exhibits show that Holbein could illuminate manuscripts and design metalwork and embroidery, too. It turns out that Holbein did not simply paint portraits but also could do a complete makeover, putting together a person’s entire look. Holbein was also involved in printmaking. In the major print series on display, the “Dance of Death” (ca. 1525–1526), a skeleton comes to take away people of all conditions, whether nuns, merchants, or kings. Given that his portraits preserve the memory of persons of many sorts, Holbein’s interest in death makes sense, as death is the great equalizer. Indeed, the series reminds us that Holbein’s most famous painting, a giant double-portrait called the The Ambassadors (1533, not in the show), presents the gaze with, among a host of objects representing the sitters, a white splotch at the lower center of the painting. When seen from one side, the splotch transforms into a skull and the rest of the painting fades from view.

By trying to get behind his subject matter, Holbein reminds us that the painter’s work is never a straightforward affair. From a certain perspective, portraiture epitomizes the vanity of human endeavor even as it strives to hold oblivion at bay. Of course, Holbein was in a better position than most to think about what goes into making a person. Even as he rendered appearances to spectacular effect, he embraced the idea that personhood was a sort of fabrication, negotiated between the self and society. But whereas Holbein’s Florentine contemporaries tended to take this fabrication for granted, he himself did not. If his portraits still have a hold on us, I think this is the reason: Holbein believed that there was ultimately something essential about each of his subjects that he could portray but not touch.