ArtSeen

Ellsworth Kelly at 100

On View

GlenstoneMay 4, 2023–March 17, 2024

Potomac, MD

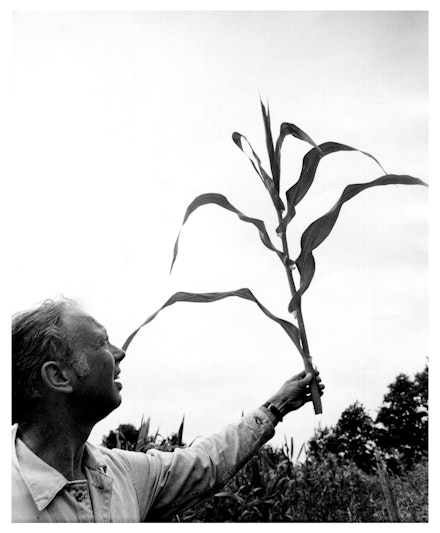

In a black-and-white photograph taken in 1973, Ellsworth Kelly holds a trimmed cornstalk up to the sky, the plant’s undulating leaves caught in flattened bends against the mute gray of the overcast day. A slight squint is visible on the artist’s face, hinting at the intensity with which he regards the object held at arm’s length. It is that sense of perpetual rapture that characterized Kelly’s seven decades of looking and making—a constant searching out and perfecting of those moments where color and form develop just enough friction to hold together as objects. In an interview conducted twenty-three years after the photo was taken, Kelly described art’s “fixity, a sense of opposing the chaos of daily living” as an illusion. What he was after was “the reality of flux, to keep art an open, incomplete situation.” To put yourself in the artist’s place, holding the lightness of the cornstalk in the wind and trying to focus on the negative space between its torquing green leaves, is to imagine the enormity of Kelly’s project, which monumentalized that very indeterminacy.

The 1973 portrait is emblematic not only for pointing to Kelly’s reverence for the natural world, but also for another important detail: the cornstalk is cut, held above the tree line to provide better contrast. From early on, Kelly understood that his art involved excision as much as it did distillation. So it is fitting that this centennial celebration of Kelly’s birth is held in the limestone pavilions at Glenstone, massive structures that cut down into a tranquil slope and offer staggered views of the landscape and water gardens from quasi-subterranean but light-filled galleries. With over seventy of Kelly’s works on view, the exhibition feels compact, but not necessarily incomplete. Presenting a full picture of Kelly’s career, with its evolutions, its endless returns to familiar motifs, and its overall scale, would require any institution to devote an impossible amount of space to the endeavor. Missing at Glenstone is Kelly’s early involvement with the figure, his automatic drawings, collages on postcards, experiments in printmaking, important paintings from the “Red Green Blue” series, and models or documentation of his architectural commissions. But what those pieces would show us—the dynamic between biomorphic and rectilinear shapes, the integration of chance, the push and pull of elements on the picture plane, the often-ignored textures in his surfaces, the optical effect of color, and the consideration of the viewer’s body as an element in an installation—is nonetheless overwhelmingly present in this survey, which advances clockwise in a rough circle, bounded by an exterior wall on which eighteen colored canvases are arrayed at regular intervals.

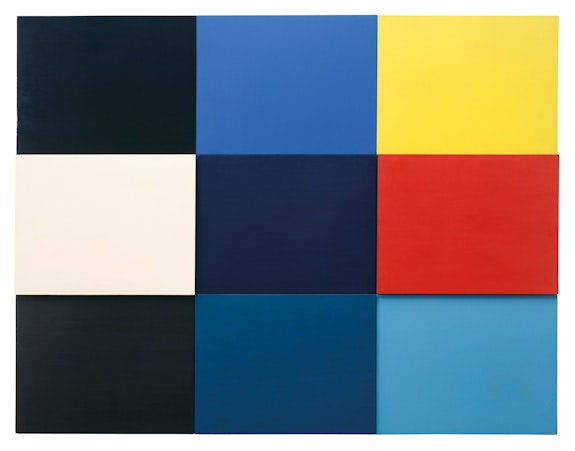

In this installation, Color Panels for a Large Wall II (1978) (like its larger iteration in I.M. Pei’s East Wing of the National Gallery), color is brought into a direct relation with architecture—here the elongated tiles of the pavilion’s gray veneer—so that the procession of chroma floats in a measured cadence along the viewer’s path. Notice three different greens and three different blues, hopscotching like arbitrarily darkened bricks on the passing wall. In reproduction, you can tell that each canvas is a different color, but in person, can you be sure the difference in hue isn’t due to shadows, glare, or the relational effects of the surrounding yellows, reds, oranges, and purples? The exhibition posits that final long stage of Kelly’s career, in which his painting and relief hybrids afford each color and shape their own panels in installation, as an endpoint that was realized relatively early in life. Each discrete gallery, then, can be seen as representing either a step toward that final product, an accessory path of development, or, in the later galleries, a confident and restless body of work within that system. The span of Kelly’s journey is not quite so straightforward, but it is hard to find fault with the momentum and economy in this description, which rightfully characterizes Kelly as a paradox: a cautious bystander to the fast-moving schools of his time and, at the same time, one of the most important figures in twentieth-century painting. His search for essence fell in opposition to the bravado of expressionistic painting, the morphology of his procedures did not fit neatly into Minimalism, and his casual choice of subjects eschewed Pop’s irreverence for an unwavering earnestness; it is not hyperbole to say that Kelly’s art forms its own solitary branch of modernism. But which piece, if any, is at the apogee of this achievement, bridging the early experimentalism and the conviction of the mature work? Glenstone’s Color Panels is a fair choice, remarkable for its indeterminate inflorescence and the way its meticulous non-pattern seems infinite within tight constraints. Each canvas is a resolute, painted thing but the whole installation becomes a kaleidoscopic vision hovering between the viewer and the wall.

Glenstone’s exhibition begins in 1949 with the artist in Paris, following his studies in Brooklyn and Boston and his service in the 603rd Camouflage Engineer Battalion (also known as the “Ghost Army,” which constructed and painted decoy tanks in WWII). The Paris paintings are already hard-edged, and Kelly is in the process of isolating objects to better show their pared-down forms. In paintings of a kilometer marker, a house plant, and a squat toilet, the hand is still abundantly visible in brushstrokes and reductive marks. While any of these could be taken as a sign of developments to come, it is Window, Museum of Modern Art, Paris (1949), that propelled Kelly most decisively toward the next phases of his career. The double-panel painting, with its painted wood framing flush with the top canvas and resting atop the lower canvas, is a stark representation of the mullions and panes of the museum’s window, but one that incorporates the subject’s dimensionality. What is striking in seeing the piece in person is its handmade qualities: the imperfect coverage of gray brushstrokes, the hewn borders, the visible grain of the wood. On the facing wall, MoMA’s Relief with Blue (1950) is slightly later, but perhaps an equally appropriate jumping-off point, as its recessed blue rectangle yields to two gentle curves (a composition based on the parting curtains of a staging of Hamlet in Paris). The early works show a preoccupation with presenting things as they are, shorn from their environments. Kelly reconstructs them as much as he represents them.

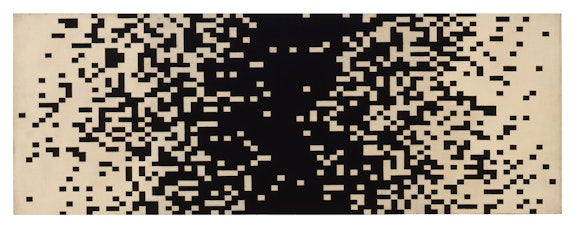

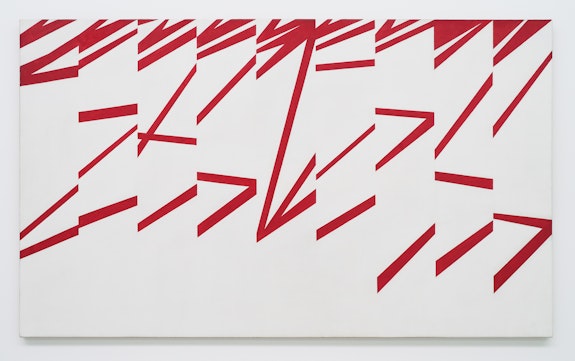

What is abundantly visible in the first few galleries is the struggle between a European and an American sensibility—not only in different approaches to abstraction but in the general feeling and scale of the canvases, in the pull of the artists, like Arp and Braque, whose paintings Kelly saw while abroad, and the Americans, whose works were only accessible to Kelly in reproduction. In the paintings of the early fifties, firmly in the oneiric and aleatory tradition of surrealism, Kelly deployed systems to avoid conscious composition, but in the process he created supremely balanced, beautiful abstractions. In the grid of Seine (1951), each successive column moving in from the white borders has one more random cell filled in with black, until they meet in a complete central black column, a pixelation that nonetheless captures the dazzling effect of light on choppy water. Gironde and Meschers (both 1951), are based on a dream that Kelly had, where schoolchildren helped him assemble massive panels on a wall. They are composed of cut-up and rearranged brushstrokes, flattened with high contrast color, and are informatively paired with the earlier and looser Cut Up Drawing Rearranged by Chance (1950). Where Seine recreated nature through mathematics, and Meschers and Gironde broke apart the autonomy of the mark, the “La Combe” works, of which two are present here, found chance in nature. In the series, Kelly traced the shadows of a handrail on a metal staircase at different times of day, each step dividing the composition into vertical sections for the sharp diagonals to fall against. In another work in the series, not on view here and not exhibited since 1951, Kelly combined multiple elements of chance by giving his students a prompt based on the sun’s movement across those same stairs, and chose one drawing to later enlarge into a painting, subtitling it Collaboration with a 12-year-old girl.

Part of the show’s early strength is that each individual gallery shows the perfection of a particular mode of working before suggesting another stage of development, and the neat narrative holds—for the most part—as you advance through different phases of paintings. But, in turning back and considering pieces laterally, the paths of Kelly’s development become more tangled, more cyclical. While the final French gallery would initially have you believe that the “La Combe” method of working was minor compared to the breakthrough of automatic techniques and gridded color, the subsequent gallery of New York paintings shows Kelly all but abandoning the forced chance of pieces like Seine. Even in comparing Sanary (1952) and Méditerranée (1951–52) with Meschers and MoMA’s (absent) Colors for a Large Wall (1951), it is clear that Kelly was learning to trust his internalized observations of the world, to place colors next to each other by feeling and not by a toss of the dice.

What is even more telling is that so many of these works from the last years in France—which on the surface are about finding an impersonal method of composition—bear titles indicating Kelly’s proximity to water: the rivers Seine and Gironde, the coastal town of Meschers, the Sanary harbor, and of course, the Mediterranean. More than any single way of working, what propels Kelly’s early work is his fixation on certain effects of light—the dappling of a streetlight on a river, the garish hulls of moored boats, the slow and ruthless advancing of shadows. It would have been disruptive and informative in these galleries to include some of Kelly’s sketches from the same period depicting light reflections on water, which range from the elegiac to the alien. They show an artist failing, in so many novel ways, to put down on paper a flashing that had already disappeared before the pen hit the page.

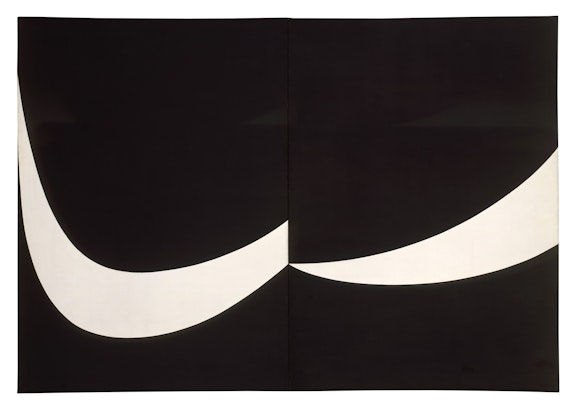

No coincidence, then, that his masterpiece in black and white, Atlantic (1956), also comes from a transitory moment of light and shadow. Two years after returning to New York, Kelly was on a bus but kept getting distracted by the fast-moving shadows of poles and other passing objects falling across the pages of the book that he was reading, so he took out a pencil and tried to quickly trace the curved lines on the paperback. Atlantic is the scaled-up image of one of those tracings, with the paper’s white and the shadow’s black reversed. Light and dark meet meticulously at a central point of inflection where the book’s center spread would be, a division also dramatized by the actual border between the painting’s left and right-hand panels. It is momentum, over everything, that is felt in Atlantic’s flattening of the artist’s experience on the bus, the way that its speed pulls you in closer but also guides the eyes back and forth along its swooping bands. In the gallery, Atlantic is paired with Kelly’s subsequent explosion of color, his isolation of individual canvas panels, and a renewed insistence toward the sculptural element inherent in his work.

Before returning to the paintings and sculptures, Glenstone’s curators have installed an intermission of sorts, two rooms filled with Kelly’s drawings and photographs. In the drawings, which are mostly contour studies of plants isolated on the page, Kelly’s facility is on full display. Just as his paintings find something essential in the sparest use of color and shape, the drawings test a singular line’s ability to describe form. They are at their best when they are speedy and economical, as in a 1966 sketch of oranges on a table, its nine floating orbs devoid of any context or texture yet communicating depth and vitality in the simplest bumps and turns of a wrist. The photographs, which have not been widely shown, give insight into Kelly’s searching way of looking, and allow us to get as close as possible to literally seeing through his eyes. Of course, many of the motifs and shapes in Kelly’s paintings are easily identifiable here, as in the irregularly patched stripes of a beach cabana in Meschers, or the high contrast curve of a snowy hill observed in Austerlitz, NY. But the photographs should not be thought of as referent studies for the paintings. Rather, they are a parallel engagement with the world, premonitions or refrains of the forms Kelly so carefully transmuted between eye and hand.

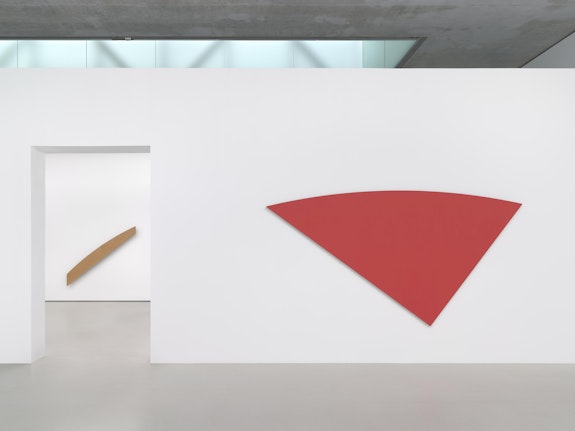

When the galleries resume their rough chronological progression, the artist is now out of the city, upstate in Chatham, then Spencertown, where he would live until his death in 2015. The Kelly of the seventies and beyond is supremely confident, working at a larger-than-life scale, allowing his shapes to project further off the wall, and constructing them not only out of canvas, but wood, steel, and painted aluminum. The paintings on canvas are shaped to increasingly exacting dimensions, their relationship to the wall and floor now visibly controlled by the demands of installation, so that the galleries themselves become grounds against which these bright visions jump and stream past. The entire jubilant second half of the show, representing four decades of production, is less a place for commenting on the incremental progression of the work, and more an opportunity to look back and recognize early ideas from France and New York now being realized to their fullest potential. There is, for example, Concorde Relief (2009), a ninety-degree rotation of the composition found in a 1958 wood relief of the same name. While the wood’s grain lends the small relief a rushing verticality, the painting’s dramatic black and white panels create a flickering play of figure and ground, so that the black piece, which rests on top of the white, can be seen as an opening receding into the wall. Compare, too, the optical effects in Spectrum IX (2014), a color wheel unfolded into twelve vertical bands, with Seine’s attempt at systematizing the dazzle of light on a river. Up close, Spectrum’s thin strips of color create an illusory fluting effect, and the whole painting contracts toward the center. The subject in Seine and Spectrum is the same: the joy of seeing, except in Spectrum there is no longer a need for the middle step of a referential memory. The color is enough. There is also, in the late work, an overwhelming presence of diagonals, both in the tangents to Kelly’s arcs, and in the borders of his trapezoids and other lopsided shapes. To me, this tendency toward the diagonal traces all the way back to the “La Combe” works and their struggle to grasp the effect of shadows on those stairs, the way that time reveals itself in elongating tangents to the sun’s own arc across the sky. In Kelly’s most mature works, the panels themselves become like light and shadow, vibrating at the peripheries, holding you for a moment or two in their orbit.

When he was interviewed for PBS in 1997, Kelly recounted an early memory: he was three or four years old living outside of Pittsburgh, and the milkman had just delivered a bottle of milk and a pound of butter to the front door. The young Kelly took that pound of butter and stepped on it, flattening it into the ground with his foot. “Here was this great yellow shape. That was my first painting, and I’ve been flattening everything ever since.” Nowhere is Kelly’s flatness-as-painting paradigm exemplified more dramatically than in a separated room at Glenstone, a coda to the exhibition, which houses a single work, the massive Yellow Curve (1990). Originally conceived for an exhibition at Portikus in Frankfurt, it is Kelly’s first foray into full-scale, site-specific installation. The room at Glenstone was built to the exact specifications of the Frankfurt show, and the piece was restaged under the artist’s supervision before his death. The painting, a yellow triangle with a curved base measuring roughly twenty-five feet on each side, sits flat on the gallery’s floor, its surface only an inch above the ground, and one of its points facing toward the entrance. Because of its scale, and because the curve is facing away from the viewer, it is impossible to get a good picture of the entirety of its shape, and shifting back and forth in front of it only confuses the vision with variable foreshortening. Only once you accept the futility of that task does a subtler detail come into focus: the diaphanous glow that suffuses the space, climbing up from where the other two points of the triangle touch the walls. It conjures imagery as grandiose as stained glass and as intimate as a buttercup held up to a chin.

That intimacy—even, sensuality—is present throughout the exhibition, not only in the suggestive curve of a panel in relief or the tenderly described petals of cyclamen, but in the overall exactitude of Kelly’s forms. It is less a perfectionism than an attraction that has turned into devotion. But devotion to what? Perception, surely. The immense gift of seeing with vigor. How each new color seems to have always been there, right in front of you. What connects Kelly’s work, more than anything, is its grace.