History of the Kaonde People of Kasempa District

KASEMPA

“Kasempakanya Bantu Biseba!”

“One Who Disarrays the Skins of People!”

The name Kasempa comes from an honorific title or ‘nickname’ given to a powerful Kaonde chief whose real name was Jipumpu who lived in the 1800s. The story behind this name has been told for generations. Chief Jipumpu was a very strong warrior who could attack his enemies unexpectedly. His enemies usually did not even have enough time to dress up for battle, or even get dressed at all, and so they would run away with their clothes flying around behind them in disarray. Because of this, the Kaonde people developed an expression, saying: ‘Kasempakanya bantu biseba’. This expression means, ‘The one who causes disarray of skins.’ (In those days, most Africans wore animal skins for clothing, so the word “biseba” [skins] refers to the animal skins that they wore.) Jipumpu would cause a disarray (kusempakanya) of animal skins, hence the name “Kasempa.” In time, the name Kasempa became more prominent than his real name, so he came to be widely known as Kasempa, and so did his chiefdom and his chieftainship.[1]

ORIGIN

The Kaonde people of chief Kasempa were once part of the Sanga chiefdom under chief Mpande. They were a clan known as “Batumba” (meaning ‘rain water’ clan; ‘Batumba’ comes from ‘kutumba kwa mvula’ meaning ‘the thunder of rainfall’.) They were close relatives of the Balonga clan (water clan), who broke away from Sanga chiefdom in the early 1700s.

The Name “Bena Kyowa”

When they were still in Katanga, the Batumba started using a new name called “Bena Kyowa” (the ‘Mushroom’ clan). The story behind this name is that: Some members of the Batumba were walking in the jungle, coming from the burial of their brother. Along the way, they found some mushroom, which they collected with their friends, but later ate alone. When their friends heard what they had done, they said: “You are greedy people. You have eaten the mushroom which we found together. Therefore we shall call you ‘Bena Kyowa,’” (meaning “Mushroom people”). [2] That is how they came to be called “Bena kyowa.”

When succession conflicts arose over the next chief Mpande, the Bena kyowa decided to break away and migrate south. This was in the late 1700s, before the days of the Bayeke King Mwenda Msidi. [3] Because of the threat of attacks from the expanding Luba Kingdom, the Bena kyowa decided to seek protection from the Lunda chiefdom. They obtained a royal emblem and appointed a new chief Kiboko, and they recognized the Lunda Paramount chief Musokantanda as their overlord. They continued migrating, and by the early 1800s, they reached the land where their relatives the Balonga had settled (modern day Solwezi). The Balonga, who were now known as Bakaonde, allowed the Bena kyowa to enter their land freely, and to cross over down south, in search of territory that would become their new home. Down south, the Bena kyowa found the Bambwela people and defeated them, and took over their land. Please note that during all of that time, the Bena kyowa did not call themselves “Bakaonde,” nor their language as “Kikaonde.” They probably called themselves “Basanga.” [4] It was the Bambwela people who begun calling them “Bakaonde”, because as far as language and culture was concerned, the Bamwela did not see any difference between these Bena kyowa who had just come, and the Bakaonde (the Balonga) whom they had known for a many years. The Bena kyowa did not resist the name ‘Bakaonde” since it was the name of their relatives. They chased the Bambwela and settled in the area around the Mafwe and Luma rivers, and they began calling their new land as ‘Kaonde Land’ (‘Kyalo kya Bakaonde’).

KAONDE VS LOZI

When the Kaonde settled in this land, their joy was short-lived. They were met with pressure from the fast-growing Lozi Kingdom, under King Lewanika, who strongly held claim to the land in which the Kaonde had settled. In fact, the Lozi strongly believed that the whole territory of land occupied by the Kaonde, the Lunda, Luvale, Bambwela, Bankoya and other smaller groups of people, was their land, all of which they referred to as Barotseland. So they demanded that the Kaonde pay tribute for settling on this land.

The Lozi were more populous and more powerful than the Kaonde, mainly because they were more united and only had one overall King, while the Kaonde were divided, with each group being ruled by a small chief. In addition, by the time the Kaonde reached this land, the Lozi had already interacted with British officials under the British South Africa Company, so in the eyes of the Kaonde, the Lozi had a powerful friend, the white man (muzungu). The Lozi for their part had two main objectives: To expand their kingdom; and to control all mining activities in the lands that they ruled. And the only way to achieve these goals was to conquer and subdue smaller groups of people. King Lewanika assigned Indunas (representatives) to pass through Kaonde land to collect tribute for him. However, the Kaonde under chief Kasempa refused to oblige. Although the Kaonde were smaller and less powerful in comparison with the Lozi, they did not succumb to Lozi pressure, thanks to the resilience of one Chief Kasempa Jipumpu. [5] Who was Kasempa Jipumpu?

JIPUMPU

Jipumpu was a mighty hunter and was the cousin of Chief Kiboko Kabambala. However, there was constant conflict between Kabambala and Jipumpu, perhaps because Kabambala feared that Jipumpu might someday violently take over the chieftainship, since he was a mighty hunter. Finally, in the year 1880, Kabambala treacherously attacked Jipumpu’s village and carried off his wives. In retaliation, Jipumpu attacked Kabambala in the forest and killed him. Kabambala’s escaped, although badly wounded. He sought help from the Bayeke and attacked Jipumpu, forcing him to run away. However, perhaps a year later, Jipumpu came back and defeated all who opposed him and set himself as chief in the year 1882. [6] When the Bayeke warriors from King Msidi came and attacked him, Jipumpu defeated them. By this time, Jipumpu had built a reputation for being a mighty warrior, and the name “Kasempa” (kasempakanya bantu biseba) had developed. When he set up his capital at the Kamusongolwa Hill, he called his capital, “Kasempa.” And by 1902, when the British opened their first administrative station (boma), they called it Kasempa. Thus the name became established. Of course, the Lozi knew Jipumpu, and they attacked him.

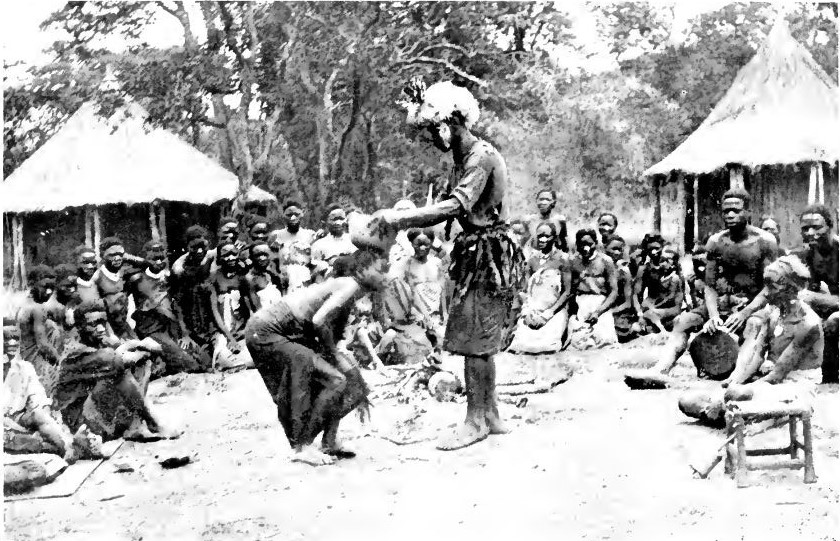

THE KAMUSONGOLWA WAR- A Battle on the Hill of Skulls

This war took place in 1898. The Lozi king Lewanika was eager to dominate the Kaonde, particularly those in Kasempa. In fact, Lewanika had heard much about the new Kaonde chief, Kasempa, whom some people even compared to Shaka the king of the Zulu. So he was curious to demonstrate his kingly power over Jipumpu. Earlier, Lewanika had sent his subordinate chief Kahari of the Nkoya, but Jipumpu defeated Kahari and his army. Thus in 1898, Lewanika sent an army coalition which included some members of the Kaonde chief Mushima. (Mushima supported Lewanika in fighting against Jipumpu because he wanted to retake his wives who had been captured by Jipumpu’s sons.)

With this army, the Lozi attacked the Kaonde. During the battle, Kasempa Jipumpu climbed the Kamusongolwa Hill, and when the Lozi warriors tried to capture him, he fought them off, and killed many of them. Those who survived escaped for their lives. After this battle, Lewanika did not attempt to attack Kasempa again. Because of this victory on the hill, the Kaonde began to revere the Kamusongolwa Hill. It came to be known as “the Hill of Skulls,” owing to the fact that human skulls and other relics of the Lozi-Kaonde war abounded on the hill. Author Dick Jaeger notes: “On poles around the stockade [erected by Kasempa Jipumpu,] there were many human skulls of the warriors he killed.”[7] In fact, even by the 1950s, Kaonde people still feared the hill. When William Grant was sent to Kasempa to serve as court judge, the local people discouraged him from climbing the Kamusongolwa hill, saying it had ghosts, venomous snakes, and killer bees. Still, William with his young cadet, Victor Magee, climbed the hill up to the top, and of course, they found no ghost, and, thankfully, met no snakes or killer bees.[8] Archeological findings show that the Kamusongolwa Hill was previously inhabited by an ancient people before the Kaonde. In fact, the rock paintings on this site date back to 11,000 B.C., and a cave excavated in the hill contained implements used for iron and copper smelting. These finds show that the hill was used periodically for thousands of years.[9] Today, at the foot of the hill stands a district prison, and local chiefs have repeatedly requested the government to make this hill a heritage site. Among the Kaonde, the story of the war on Kamusongolwa is passed on from generation to generation.

Jipumpu knew why the Lozi had attacked him. So to avoid further conflict, he sent gifts of reconciliation to the Lozi king. Lewanika certainly recognized this as a payment of tribute, but this was last that the Kaonde ever paid to the Lozi, and Lewanika himself did not see it expedient to demand further tribute from Kasempa Jipumpu. In fact, he is said to have had “a great liking for the Kaonde chief.”[10]

On Whose Side Were the British?

The British, by means of the British South Africa Company (BSAC), were interested in the mineral reserves in the Barotse and Kasempa areas. However, they had two challenges:

1. The Lozi kingdom was well organized and too ambitious to deal with.

2. The Kaonde were too disorganized and disunited, making it administratively difficult to bring them all under proper control.

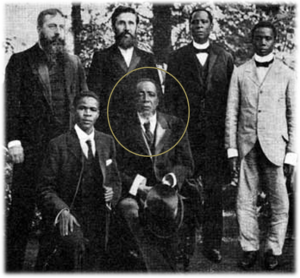

Hence, the British seemed to focus more on establishing a protectorate agreement with the Lozi king Lewanika, which Lewanika very much wanted, despite being discouraged from doing so by his own advisers. Thus for a time, the BSAC showed disinterest in the welfare of the Kaonde, and only sent officers in the company of Lozi indunas to Kasempa from time to time. It was not until 1902 that the first administrative office in Kasempa was opened by Sub-inspector F. C. Macaulay, and Captain Stennet of the Barotse Native Police. Cpt. Stennet was put in charge of police. Using his alliance with the British, Lewanika tried to force Kaonde chiefs to obey him as paramount chief. At one time, Lewanika sent his induna with a letter to all Kaonde chiefs, saying: “This is my Induna [whom I have sent] to collect the Kahondi [Kaonde] Chiefs.” However, this letter was intercepted by Macaulay, and Lewanika’s intentions were thwarted.

In 1904, E. A. Copeman took over from Macaulay. Copeman was even more determined to protect the Kaonde from Lozi influence. Lewanika then appointed an induna to stay in Kasempa and continually collect tribute from the Kaonde. The induna arrived in Kasempa on July 1, 1905, but he left almost immediately, because he had left his wives and his cattle behind. Lewanika sent another sub-chief, Setenge to collect tribute, but Copeman refused to allow Setenge to collect tribute. Later that year (1905), three indunas were sent to fetch chief Kapijimpanga from Solwezi and take him to Lewanika, with the goal of forcing him to accept Lewanika as his overalord. Again, Copeman intercepted them. It was at that time that he declared that no Lozi could come into Kasempa without a permit from the administrative office in Kalomo. Later, Frank H. Melland, who was Solwezi District Commissioner (1911-1922), also did his best to protect the Kaonde from Lozi interference. In fact, much of what these men did in resisting Lozi influence on the Kaonde people was actually against BSA Company policy. The BSAC wanted Lewanika to feel assured of his supremacy over the natives, in order for BSAC to sustain and manipulate the agreement with Lewanika in their favor, given that Lewanika did not fully understand the terms of that agreement. Still, Macaulay and Melland’s resilience and sympathy for the Kaonde deterred the Lozi from dominating the Kaonde.[11]

Kasempa Becomes A District

“There are many [towns] with an earlier history than Kasempa, but there are few, if any, which have remained on their original site for half a century.”

–Northern Rhodesia Journal, Vol. II, No. 5 (1954)-Kasempa: 1901-1951, p. 62, par. 1, by D. Clark

Kasempa was established as a district by the British administration in 1902. The main reason why the North-Western Rhodesia administration decided to set up an administrative office in Kasempa was to secure the copper deposits that had been found in Kaonde territory by Scottish explorer George Grey, and to stop the downward progression of slave traders from Portuguese Angola.[12] Before the office was opened, two officers, Sergeant Major Mobbs and Trooper Lucas, were sent as an advance party in 1901. They recruited messengers and pitched a camp at the place where the Kasempa office (boma) would be built. Then in 1902, Sub-inspector Frederick C. Macaulay and Captain Stennet arrived and took over the administration Kasempa District. Cpt. Stennet (from Barotse Native Police) was in charge of police. The office was opened near Chief Kasempa’s capital, and thus the district was named Kasempa. Initially, Kasempa District was very vast, as it also included Kansanshi sub-district (later named Solwezi district), and Mwinilunga. It was what we would call a province today. Shortly afterwards, in 1905, Chief Kasempa Jipumpu died, and he was succeeded by his nephew Kalusha. Kalusha was inaugurated as chief in 1907.

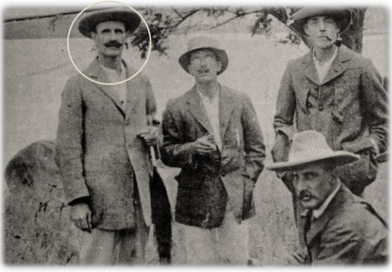

Shakutenuka

A memorable event took place in Kasempa in the year 1911. It involved the killing of a Swedish store man named Ohlund. Ohlund was employed by a fellow Swede named Wilhelm Frykberg. Wilhelm Frykberg was a Swedish trader who was born in 1876. In the year 1900, he went to South Africa with the hope of going back to Sweden in a few years. However, while in South Africa, he joined the army until the end of the Boer War. When the Boer War ended, Frykberg joined the British South Africa Police. Sometime between 1905/1906, Frykberg was sent to Kasempa, initially as part of a police regiment in which he was Sergeant Major. In Kasempa, he was fondly known by the local people as “Bwana Mecha” (“Mecha” meaning ‘Major’ from his rank as sergeant-major).[13] However, he decided to leave the Police and took over a store that had previously been run by a European named Ullman.[14] At first, Frykberg prospered, so much that by the year 1910, he had opened a number of stores, including one at Kansanshi (now Solwezi). He employed two Swedish friends to work for him; one of them was named Ohlund. Frykberg also began to recruit Kaonde men from Kasempa District to go and work in the Rand Mines in Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). Between 1909 and 1910, he recruited more than 400 Kaonde men. However, the working conditions for these recruits were miserable. The weather was very cold down south, and they had no proper covering. As a result, almost 100 of those men died of pneumonia before they could return home. This angered their Kaonde relatives in Kasempa, so they began to seek vengeance for the death of their relatives. In May 1911, three Kaonde men, namely Tumiwa, Tapoka, and Kungwa, set out to kill Frykberg. However, Frykberg had gone to Mwinilunga, where his wife was giving birth to their firstborn son, Eric, at Kaleni Hill Mission. Disappointed that they could not find Frykberg, the three men decided to attack Ohlund, who was Frykberg’s assistant. Ohlund was in his house at a village called Shindamana. When the three men found him, they shot through the window and killed him. The three murderers then ran away from the murder scene, and it took nearly a year to catch them. The District Commissioner, W. H. Hazell carried out a vigorous operation to capture the murderers. He raided villages at night and rounded up more than 40 people, including women and children, until the three men were caught. Then on 11th November 1912, the three men were killed by hanging. Before being hung, one of the murderers, Tumiwa, made a fearless public confession of the murder and said the intended target was Frykberg. Tumiwa was a fearless man and a former messenger who wanted to demonstrate his defiance to the white maters. After these events, Tumiwa came to be known as “Shakutenuka,” due to his defiant attitude. The hanging of Tumiwa and his friends had a deep impact on the Kaonde people in Kasempa. True, they learnt the hard way that killing a white man would have strong consequences, but they also became very resentful of Hazell and Frykberg. In fact, two years later, when recruiting agents went to Kasempa in search of men to recruit for work in the mines, the attitude of the local people was so bad that the agents decided that “further recruitment could not be undertaken” among the Kaonde in Kasempa. More to that, Commissioner Hazell lamented that the Kaonde, “especially the younger men, [often] resent the arrest of any of their friends,” and often show “a determination to take revenge,” since they possess weapons. The Kaonde did indeed possess some weapons, especially during World War I, when much ammunition from South Africa passed through Kasempa and Solwezi en route to the Katanga region. At least about 1,000lbs (pounds) of gunpowder is reported to have passed through Kasempa. The threat was so real that early in 1912, there is reported to have occurred ‘an attempt to murder a government officer, Mr. Dillon, at Kansanshi,’ and the local people shielded the attempted murderers from being arrested. [15] Today among the Kaonde, the story of Shakutenuka is recited, not as a reminder of the repercussions of his actions, but as a reminder of his courage.

What Happened to Frykberg?

After the murder of Ohlund and the hanging of the three natives who killed him, Wilhelm Frykberg suffered great setbacks in his investments in Kasempa. To start with, he could no longer hire the local men for labor, and secondly, he lost the trust of the natives, and this negatively impacted on his business there.[16] Frykberg decided to venture into other business opportunities. So in 1913, Frykberg asked his younger brother, Kola Frykberg, to take care of his store in Kasempa, while he went to Sweden where he acquired financial support from some wealthy family members to set up a trading company in South Africa. By 1915, he was established as the manager of a company called Anglo Scandinavian Trading Company, in Cape Town, South Africa. By that time, Frykberg’s store at Kansanshi had been shut down due to the war (WWI), and Frykberg seemed more interested in furthering his business opportunities in South Africa. Frykberg ambitiously bought estates in Kasempa and Mwinilunga and employed fellow Swedes to manage these farms while he was in South Africa. However, by 1918, the company had fallen and was facing liquidation. The reason for the company’s failure was that “Frykberg lacked the training and the exp[e]rience to run a big [company]. He was reckless and extravagant.”[17] After liquidation, a new manager, R. C. McGrillivray, took over the farms and stores in Northern Rhodesia.

Frykberg was deeply disappointed over his failure. When the Second World War started, Frykberg joined the service, doing guard duties on various locations, despite being over 60 years old then. The biggest blow came in 1942, when his son, Eric Vickers Frykberg died in a plane crash. This was the same son who was born at Kaleni Hill in Mwinilunga in 1911, at the time when the three Kaonde men killed Ohlund. Eric grew up and joined the South African Army, and by the time he was 30 years old, he had risen to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel.[18] Sadly, while fighting in World War II, Eric died in a plane crash at Lake Victoria in Kenya, on 19th December 1942. He was just 31 years old. Frykberg was devastated by the death of his son. Eight years later, on 3rd June, 1950, Wilhelm Frykberg died in South Africa, at the age of 73.

HISTORY OF THE KASEMPA CHIEFS

(The following is a brief narrative and list of Kasempa Chiefs)

REFERENCES

1 & 2. Settlement patterns and rural development: A Human Geographical Study of the Kaonde, Kasempa District, Zambia pp. 60-63, Dick Jaeger

3. In Witch-Bound Africa, pp. 31-33, by F. H. Melland, 1923

4. Kate Crehan, The Fractured Community, pg. 70, par.1

5. The International Journal of African Historical Studies, Vol. 5, No. 1 (1972), pp. 22-40, “The Kasempa Salient: The Tangled Web of British-Kaonde-Lozi Relations” by Stanley Shaloff

6. “Kaonde History” by S. J. Kibanza, Central Bantu Historical Texts 1, Rhodes-Livingstone Communication No. 22, pp. 45-67 (Lusaka, 1961)

7. Fifty Years of Kasempa District, p. 81, note 8, by Dick Jaeger.

8. Zambia Then and Now: Colonial Rulers and their African Successors, p. 43, par. 2, by William D. Grant

9. Zambia Then And Now: Colonial Rulers and Their African Successors, Page 43, par. 1, by William Grant; Fifty Years of Kasempa District, p. 81, note 8, by Dick Jaeger

10. A.D.C., Lealui, to Sec., Administrator’s Office, June 30, 1904, KDE’ 1/5/1, National Archives of Zambia

11. The International Journal of African Historical Studies, Vol. 5, No. 1 (1972), pp. 22-40, “The Kasempa Salient: The Tangled Web of British-Kaonde-Lozi Relations” by Stanley Shaloff

12. Northern Rhodesia Journal, Volume II, No. 5 (1954)-Kasempa: 1901-1951, pp. 62-70, by P.G.D. Clark

13, 14. Northern Rhodesia Journal, vol. III, No. 1, 1956, pp.34, 92, 93

15. THE BRITISH ANNEXATION OF NORTHERN ZAMBEZIA (1884-1924) ANATOMY OF A CONQUEST, pp. 402-405, by Fergus Macpherson

16, 17. Northern Rhodesia Journal, Volume III, No. 1 (1956)-The “Swedish Settlement” in the Kasempa District, pp. 34-43, by S. Grimstvedt

18. http://www.genealogy.com/ftm/f/r/y/Patricia-D-Frykberg/WEBSITE-0001/UHP-0013.html; Northern Rhodesia Journal, Volume III, No. 1 (1956), p. 42