In 1844 a German doctor (and later psychiatrist at a psychiatric hospital in Frankfurt) was looking for a book to give his three year old son for Christmas but couldn’t find anything suitable, considering the books on sale to be too long and moralising. He decided to create something himself instead, being accustomed to sketching pictures to pacify child patients. This was Heinrich Hoffmann and his creation was Struwwelpeter, a short illustrated collection of cautionary tales which graphically demonstrated what would happen to children who misbehaved or disobeyed their parents. His bestselling book is one of the most well-known works for children in Germany, running to more than 700 editions, translated into more than 40 languages and with many imitations and parodies. There is even a museum dedicated to Struwwelpeter and Hoffmann in Frankfurt am Main. In this blog post we explore in more detail the original book and some of the many versions of it.

In 1844 a German doctor (and later psychiatrist at a psychiatric hospital in Frankfurt) was looking for a book to give his three year old son for Christmas but couldn’t find anything suitable, considering the books on sale to be too long and moralising. He decided to create something himself instead, being accustomed to sketching pictures to pacify child patients. This was Heinrich Hoffmann and his creation was Struwwelpeter, a short illustrated collection of cautionary tales which graphically demonstrated what would happen to children who misbehaved or disobeyed their parents. His bestselling book is one of the most well-known works for children in Germany, running to more than 700 editions, translated into more than 40 languages and with many imitations and parodies. There is even a museum dedicated to Struwwelpeter and Hoffmann in Frankfurt am Main. In this blog post we explore in more detail the original book and some of the many versions of it.

Hoffmann did not intend his little book of illustrated verses to be anything but private. However, he was persuaded to publish by friends, and so in 1845 Lustige Geschichten und drollige Bilder für Kinder von 3–6 Jahren (Funny stories and droll pictures for children aged 3-6) was published. Hoffmann’s title suggests humour but the stories are known for being quite violent and seemingly terrifying for their young audience. The first edition sold out in four weeks. By 1847 the book was renamed Struwwelpeter (after one of the featured characters) and expanded to the standard set of ten tales:

- Struwwelpeter (Slovenly or shockheaded Peter with tousled hair and uncut fingernails)

- Böser Friederich (Cruel Frederick, bitten by the dog he whipped)

- Feuerzeug (Pauline/Harriet and the matches; she plays with matches and burns to death)

- Schwarze Buben (The inky boys, dipped in ink for teasing a black person)

- Wilder Jäger (The wild huntsman who falls into a well when shot at by the hare, his prey)

- Daumenlutscher (Conrad the thumbsucker whose thumbs are chopped off by a tailor’s shears)

- Suppen-Kaspar (Soup Casper/Augustus who dies after rejecting his soup for several days)

- Zappel-Philipp (Fidgety Philip who pulls everything off the table when he rocks on his chair)

- Hans Guck-in-die-Luft (Johnny look-in-the-air who falls in the river)

- Fliegender Robert (Flying Robert who with his umbrella is dragged into the sky on a windy day, never to be seen again)

The University Library does not have any 19th century German language editions of Struwwelpeter but it does have several from the first half of the 20th century and full text access here via Project Gutenberg. One strikingly different 20th century rendition in our collection is … und noch einmal Struwwelpeter: moralische Geschichten für Kinder von 18-80 Jahren (1994.8.2895) by Waltraut Nicolas with stylised illustrations by Horst Lemke who was best known for illustrating Erich Kästner’s books during the 1950s. Nicolas’s version dates from 1947, a few years after she was deported back to Germany from the Soviet Union (her husband, Ernst Ottwalt, a German writer who had collaborated with Brecht, died in a gulag in 1943, a fact that was not revealed to her until 1958. To find out more about him see P746.c.208.7). Another interesting 1950s interpretation is by Wolfgang Felten in Struwwelmax (Waddleton.c.1.513) in which Struwwelpeter is combined with Max und Moritz, another German favourite.

Over the years we have acquired a wealth of English language versions and adaptations including a rag book (1906.11.87), colouring book (1901.10.62) and an 1890 book with moving parts (Waddleton.a.1.264). We also have a translation by Mark Twain, done in secret as a Christmas present for his daughters while living in Berlin in 1891 but not published until 1935 (S700:01.a.1.214). Click on each image below to see larger versions and further details.

Full text access to an English translation is available here via Project Gutenberg. Among other translations is a charming 19th century Dutch one, Een nieuw aardig prentenboek (Waddleton.a.5.9) with some overlap of characters – for instance Hans Guck-in-die-Luft becomes Hans-kijk-in-de-lucht with recognisably Dutch surroundings:

Countless adaptations and parodies of Struwwelpeter have been produced, both here and in Germany:

-

- In the 1880s a gynaecologist used it as a base for Kurzer gynaekologischer Struwelpeter (Uc.8.7058).

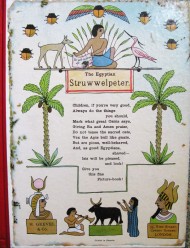

- The Egyptian Struwwelpeter (1896.10.128) appeared in the 1890s, set in Egypt and merging the title story with the inky boys in Thoth the Inky Boy.

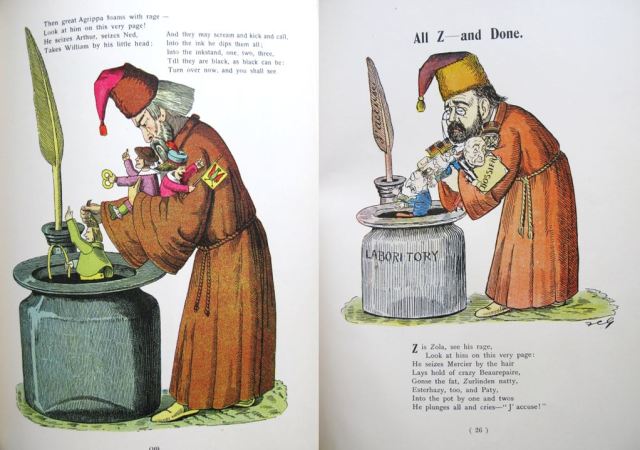

- Around the turn of the century Harold Begbie collaborated with the caricaturist Francis Carruthers Gould on two works intended for an adult audience familiar with the original children’s work, The political Struwwelpeter (1899.10.97) and The Struwwelpeter alphabet (1900.10.31) depicting British royalty and other eminent figures.

- Swollen-headed William (1919.9.299) about Kaiser Wilhelm was created in 1914 by E.V. Lucas of Punch magazine, featuring black and white drawings very close to the originals by George Morrow.

- Spin-offs featuring female characters also occurred eg. Struwwel-Liese (Waddleton.b.1.382 and Waddleton.b.1.483) and Slovenly Betsy (2014.11.1408)

- In 1941 a British anti-Nazi version, Struwwelhitler, was published (Newnham College Library)

Covers of 2 versions of Struwwel-Liese (Waddleton.b.1.382 & Waddleton.b.1.483)

Covers of 2 versions of Struwwel-Liese (Waddleton.b.1.382 & Waddleton.b.1.483)

If you are interested in the evolution of the Struwwelpeter phenomenon you can find relevant further reading by searching in the catalogue under the keyword Struwwelpeter. Perhaps the most comprehensive book on Hoffmann is Heinrich Hoffmann, Peter Struwwel: ein Frankfurter Leben 1809-1894 (C207.c.4424), the catalogue of an exhibition held on the 200th anniversary of his birth which includes his original (and very different) 1844 illustration for Struwwelpeter (partially shown on the cover here). And for more detail on the many versions I would recommend “Böse Kinder” : kommentierte Bibliographie von Struwwelpetriaden und Max-und-Moritziaden mit biographischen Daten zu Verfassern und Illustratoren (746:17.c.95.650) – over half this bibliography (the rest concentrating on Max and Moritz) is devoted to Struwwelpeter with details of what went before and an exhaustive list of editions and related works including parodies and translations.

If you are interested in the evolution of the Struwwelpeter phenomenon you can find relevant further reading by searching in the catalogue under the keyword Struwwelpeter. Perhaps the most comprehensive book on Hoffmann is Heinrich Hoffmann, Peter Struwwel: ein Frankfurter Leben 1809-1894 (C207.c.4424), the catalogue of an exhibition held on the 200th anniversary of his birth which includes his original (and very different) 1844 illustration for Struwwelpeter (partially shown on the cover here). And for more detail on the many versions I would recommend “Böse Kinder” : kommentierte Bibliographie von Struwwelpetriaden und Max-und-Moritziaden mit biographischen Daten zu Verfassern und Illustratoren (746:17.c.95.650) – over half this bibliography (the rest concentrating on Max and Moritz) is devoted to Struwwelpeter with details of what went before and an exhaustive list of editions and related works including parodies and translations.

Katharine Dicks

Reblogged this on penwithlit and commented:

I wonder what Melanie Klein would have made of him?

Brilliant post, and utterly terrifying characters!

I have a nice (modern) version of the book in Sütterlin.

Amazing. Struwwelhitler seems to be channeling Edward Scissorhands there.