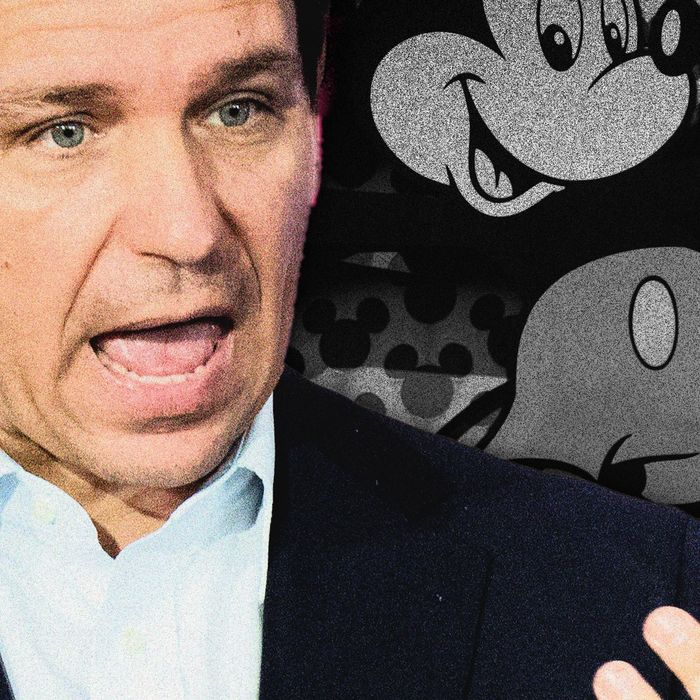

Ron DeSantis is not a subtle person. The Florida governor is fond of hearing himself talk — like a charmless Bond villain who can’t help but reveal his plans, even if doing so results in a self-destructive mess that is entirely of his own making.

DeSantis’s big mouth now appears to be his biggest liability in the nascent litigation that has pitted him against Disney, which sued him last week as part of an increasingly convoluted legal dispute that began last year — after the company mildly criticized the passage of a state law that restricts classroom discussion of sexual orientation and gender identity in schools. “I think they crossed the line,” DeSantis said at the time. “We’re going to make sure we’re fighting back when people are threatening our parents and threatening our kids.”

DeSantis then engineered a takeover of the 25,000-acre special district, known as the Reedy Creek Improvement District, that had essentially allowed Disney to run local government services in the areas surrounding the company’s Florida parks since 1967. The district’s board was replaced by a reconstituted governing panel, dubbed the Central Florida Tourism Oversight District, that is now stocked with DeSantis-aligned appointees. It seemed like DeSantis had won a major battle in his war on “woke,” which he apparently hopes will make him the next Republican presidential nominee.

In February, however, before the takeover was completed, Disney executed agreements with the outgoing Reedy Creek supervisors that ensured that Disney would be able to finish a long-term development program — including the construction of additional theme parks and hotels in the area — and gave the company veto power over the exterior design and appearance of improvements to any property in the district. DeSantis and the geniuses who work for him at taxpayer expense apparently missed all of this, even though members of the press were present for the public meetings that preceded the agreements.

Afterward, DeSantis called for a state investigation into Disney for some reason or other, and last week, the CFTOD declared the agreements void, which prompted the company’s lawsuit. On Monday, the CFTOD filed its own competing complaint in state court, alleging that Disney’s agreements were both procedurally and substantively improper under state law. Residents and business owners in the area, meanwhile, appear to be turning on DeSantis, and his presidential rivals saw an opening to attack.

Pretty much everything about this is highly unusual, but Disney’s greatest litigation asset, by far, is the extensive public record created by DeSantis and his allies, in which they explained that they were punishing Disney for speaking out last year. Among other things, the complaint quotes DeSantis telling Bob Chapek, Disney’s then-CEO, in a phone call last year that the company “shouldn’t get involved,” because it would not “work out well for you,” and announcing publicly that he would not “bend a knee to woke executives in California,” where Disney is headquartered. The complaint cites a fundraising email sent on behalf of DeSantis that promised, “Disney and other woke corporations won’t get away with peddling their unchecked pressure campaigns any longer,” and there is a litany of unhelpful quotes from Republican state lawmakers who worked with DeSantis and said, to take just one example, that Disney was “learning lessons and paying the political price of jumping out there on an issue.” DeSantis himself was publicly levying more obnoxious threats as recently as a couple of weeks ago — including building a prison next to Disney World.

The complaint essentially advances two key legal theories. The first is that the DeSantis board’s repudiation of Disney and Reedy Creek’s recently signed agreements violate the U.S. Constitution’s Contracts Clause, which prohibits states from “impairing” contractual obligations with or among private parties. The second is that DeSantis and the CFTOD’s actions violated Disney’s First Amendment rights, because they were motivated by a desire to retaliate against the company for engaging in protected political speech.

The company’s claim under the Contracts Clause would not be a particularly strong one in the absence of all of those quotes from DeSantis and his Republican allies. “The reality is that it’s very difficult to win a case against a state in which you’re claiming that the state is abridging your contract rights,” Michael Allan Wolf, a law professor at the University of Florida who has studied local government law for more than 30 years, told me. He was skeptical of the claim, “based on the current state of the law in the Supreme Court,” but noted that members of the Court’s conservative majority have expressed interest in “evolving in the direction of stronger protection for contract rights.”

Disney’s best argument relies on a relatively obscure Supreme Court case from 1977 that emerged after New York and New Jersey repealed a covenant with Port Authority bondholders that had limited the Port Authority’s ability to subsidize commuter rail. The Court noted that a state’s impairment of its own contracts “may be constitutional if it is reasonable and necessary to serve an important public purpose” but ultimately held that the states had violated the Contracts Clause, because the only thing that had really changed over time was their interest in developing a commuter rail. “There are defenses to Contract Clause claims that say that a change in situation can justify violating a contract or impairing a contract,” David N. Schleicher, a professor at Yale Law School who took more of a glass-half-full view of the current state of the law, told me, but “changing your mind as a governmental entity isn’t a good enough explanation. The Supreme Court has said that very explicitly.”

In that same case, the Court noted that the clause “does not require a State to adhere to a contract that surrenders an essential attribute of its sovereignty.” Although the CFTOD’s countersuit claims that Disney’s agreements do just that — by granting the company too much remaining power in the district — the argument is weaker than it would otherwise be in light of the public comments from DeSantis and his allies indicating that their anger at Disney’s decision to weigh in on state law is what has driven their campaign against the company. “By bringing the retaliation claims attached to the Contract Clause claim, the Contract Clause violation looks worse,” Schleicher noted, because it undermines the notion that there was a principled reason for DeSantis and his allies to try to invalidate Disney’s agreements.

The First Amendment retaliation claims, however, are surprisingly robust in their own right, thanks again to DeSantis’s and other Republicans’ own words.

“I think it’s a strong claim,” Lyrissa Barnett Lidsky, a First Amendment scholar based at the University of Florida, told me, “because even though the state had a right to revoke any preferential treatment it gives by law, it can’t do so for retaliatory reasons, and the complaint points to evidence that the state’s actions here to deprive Disney of preferential treatment were an attempt to try to punish it for its speech on a matter of public concern.” By way of example, she cited a 1936 Supreme Court case that struck down a Louisiana state tax designed to penalize newspapers that had been critical of Senator Huey Long.

Still, as Lidsky and everyone else I spoke with readily acknowledged, predicting the outcome of a complex and politically freighted legal dispute is an inherently fraught exercise, and that is true of Disney’s First Amendment claims as well. The main reason is that “whenever you talk about making motive the criteria” for a legal claim, “you’re basically leaving it up to the discretion of the decision-maker,” as Yale Law School professor Robert C. Post put it to me. “That’s what it comes down to as a matter of practice.” It’s why, for example, a legal challenge to Donald Trump’s “Muslim ban” failed when it reached the Supreme Court. “It was plain to anyone in ordinary life that it was meant to fulfill the campaign promise of prohibiting Muslims from traveling to the United States,” Post observed, but “the Supreme Court said, ‘Look, we’re going to engage in the presumption that when the executive does something, it does it for a proper reason.’”

Indeed, for their part, DeSantis and his allies have sought to portray what looks very much like a politically motivated vendetta against Disney as a principled stand against corporate influence in public life and corporate favoritism in the law — claims that could provide just enough in the way of credible rationale to support the state’s actions in court. “It’s pretty clear, I think, to the ordinary observer, that this was retaliatory and, therefore, was probably unconstitutional,” Post continued, “but whether a court will find it is is a quite different story. They’re very reluctant on the whole to point the finger of intentional discrimination at a coordinate branch of government as a general matter.”

The trial-court judge that Disney drew in its case is a particularly favorable one for the company — Mark Walker, an appointee of Barack Obama’s who has struck down laws signed by DeSantis — but he will not necessarily have the last word. Just last week, he was reversed by the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals in a case in which he had held that an election law signed by DeSantis in 2021 intentionally discriminated against Black voters.

You could be forgiven for maintaining some ambivalence about all of this — particularly if you focus on the politically and ideologically scrambled nature of the dispute between Disney and DeSantis. In other contexts, many liberals would bristle at the sort of legal effort that Disney is mounting, especially because it represents the culmination of decades of mainstream conservative jurisprudence that has resulted in private corporations acquiring increasingly expansive — and often very regrettable — constitutional rights. (The company’s behavior last year was hardly a profile in courage. It was reluctantly forced to take a very modest public stand due to pressure from protesters and advocacy groups.) By the same token, DeSantis and his allies are effectively asking the courts to reject a host of arguments that many conservative lawyers and judges would ordinarily embrace as logical extensions of the business-friendly jurisprudence that they have worked to advance with great success in the courts.

Exactly how long this litigation will last and how far it will go in the courts is anyone’s guess. In our discussion, Wolf sketched out a plausible path to an eventual out-of-court settlement between the parties. What might that look like? “The tumult over the First Amendment, the ‘wokeness,’ will die down,” he posited, “and they’ll get down to brass tacks and sort of modify the powers of what used to be called Reedy Creek,” after which the state could “withdraw its presence from the governing body” and return the situation to something approximating the prior status quo.

In the meantime, there are very real stakes for the dispute in both the short and long terms, especially as DeSantis prepares to embark on a presidential run that, if successful, would grant him far greater power to vindictively target any groups he perceives to be at odds with his political interests. You do not have to be a fan of the underlying legal architecture of Disney’s lawsuit to be worried about how easy it would be for someone as petty and small-minded as DeSantis to wreak political and economic havoc at the federal level using similarly spiteful legal tactics, and indeed, it would likely be harder to stop a President DeSantis — particularly if he had more professional and capable advisers than those that currently surround him in Florida.

In fact, it probably would not have been that hard for DeSantis and his allies to achieve their desired result — largely, if not entirely, eliminating Disney’s quasi-governmental control in the region — if they had simply managed their public statements more carefully. But of course, DeSantis appears to regard his incessant public bloviating as helpful — perhaps even essential — to his political aspirations, and though it may turn out he was wrong about that, it is unclear whether he is capable of exercising the sort of self-restraint that would have allowed him to avoid this mess in the first place.

DeSantis was supposed to offer Republicans what has become fashionable to call “Trumpism without Trump” — the same noxious politics without the grotesque personal behavior or the potential criminality. The limits of that vision are now on full display, as we watch a legal dispute unfold that is just as pointless, self-inflicted, and unhelpful to ordinary Americans as anything we witnessed during the Trump years — when we saw firsthand what it means to elect a power-hungry egomaniac to the presidency.