When Darren Campbell lists off the rebellious types who have worn Dr. Martens boots through the decades, he sounds like a genealogist charting the lineage of a species.

There’s the “consumer who is born out of subcultures, whether it be in the ’60s or the ’70s when you had punks and the two-tone and goth,” says Campbell, the global vice-president of product and marketing for Dr. Martens. “That translated through to the ’80s, through psychobillies and the scooter boys. And then in the ’90s, the guys on the Pacific Northwest—the grunge kids—and the UK Britpops came into the brand.”

That family tree of “alternative” customers, as Campbell calls them, is the one that really spread the gospel of Dr. Martens, turning it from a tiny boot company in the English Midlands into the globally recognized icon it is today. They weren’t meant to be its main audience. The boots were designed for workers—policemen, postmen, factory workers—who bought the tough, durable footwear, with its comfortable air-cushioned soles, for actual labor.

“But very quickly music got hold of it,” Campbell continues. “The most high-profile individual was Pete Townshend of The Who. He was very proud of his working-class roots, and decided that he wanted to wear a boiler suit and a pair of Doc Martens on stage basically to say to the establishment that I’m proud of coming from the working class.”

The boots, often called “Docs” in the US or “DMs” in the UK, caught on, and as the years ticked by, steadily crossed the world as a counterculture accoutrement. By now, many of those subcultures have gone extinct, and others, such as punk and goth, trudge along weakly. Still, Dr. Martens is going strong.

In recent years in particular, the company has been growing at a rapid clip, with sales roughly quadrupling from their level a decade ago. Dr. Martens has been working hard to reach new customers and new markets, particularly in Asia, where its business is growing fastest: Roughly a quarter of Dr. Martens’ sales now are in Asia, mostly Japan. The boot may still be widely synonymous with subculture, but it has clearly grown well beyond it.

The wearers of Docs are undeniably changing, which makes for a tricky balancing act for the company. Dr. Martens wants to preserve its roots, while staying relevant to shoppers who may know the Clash best as one of the bands on the Stranger Things 2 soundtrack. The company’s signature style, the 1460 boot (“1460” refers to April 1, 1960, the day the first pair rolled off the line) is more than 50 years old.

A taxonomy of the Docs wearer

How does a brand founded on decades-old designs and niche cultures function as a modern, globally relevant label today?

The answer to that conundrum, in part, is knowing exactly who its customers are. “We’ve carried out quite a lot of work recently on trying to understand our consumer,” Campbell says. The company, he explains, has narrowed Docs-wearers down to four types of shoppers.

The first two, the “industrial” and “alternative” consumers, were those early customers—the workers and then the subcultural groups that adopted the boots, who are still the core of the brand’s image. Walk into a Dr. Martens store today and the walls will likely be covered in pictures of musicians wearing Docs.

But there are also “casual” buyers, who want a long-lasting, comfortable boot but aren’t necessarily trying to make an aesthetic statement. Think of the dad who buys a pair to do work in the yard.

And then there’s the consumer who Campbell says has been a growing part of Dr. Martens’ business, the “fashion” shopper.

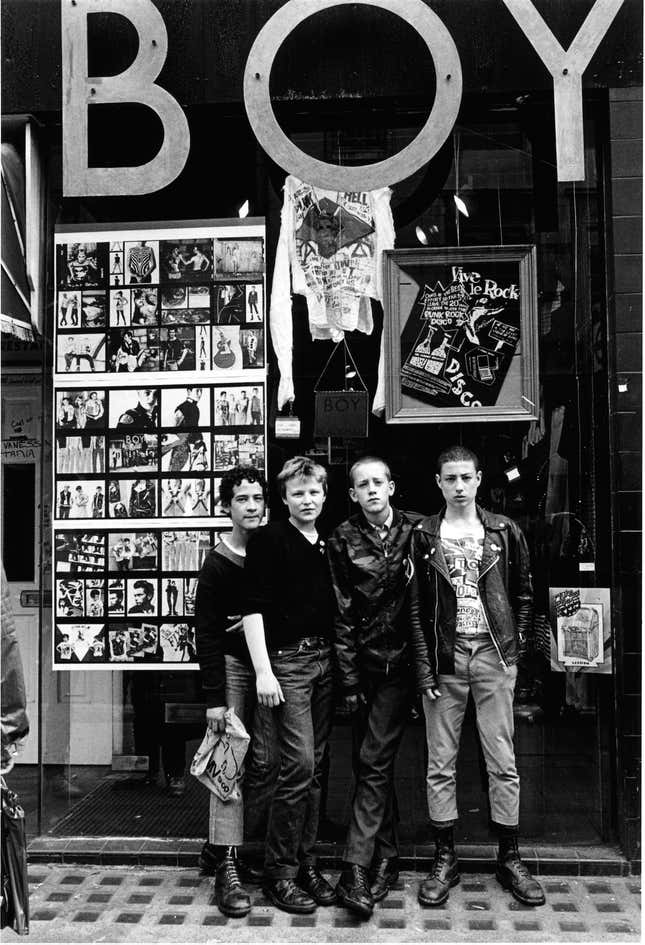

All Dr. Martens customers who aren’t buying the boots purely for functionality could be called fashion consumers to some degree. But the fashion shopper is a different breed than those who buy the boots to signal their belonging to a tribe, the way punks and skinheads did in the 1970s, as photographer Gavin Watson—a former skin himself—documented. (Skins are not all racist, by the way. The style started out as a working-class movement, and only some factions veered into racism and white supremacy.)

Often that heritage of subculture is part of the appeal for these shoppers. You don’t see many people pulling Docs completely out of that context and wearing them with an otherwise preppy outfit.

But they don’t belong to those subcultures themselves. Customers are buying Dr. Martens’ boots for how they look with a pair of jeans as much as their connotations. Today you can see fashionable young people stomping along in their Docs in the streets of London’s Shoreditch, or Williamsburg in Brooklyn, or Harajuku in Tokyo. (Campbell notes that most of the growing customer base in Asia falls into the “alternative” or “fashion” categories.)

Some have come to the brand through the high-profile collaborations it has done over the years with designer labels. Dr. Martens started working with the Japanese legend Yohji Yamamoto about 13 years ago. ”All of the collaborations we do with Yohji are based on our iconic, original items, which obviously ensures that the brand can remain relevant within fashion without us having to try to be a fashion brand, because we don’t openly want to go and chase fashion,” he explains. “But we find that fashion adopts us.”

Comme des Garçons has also been a regular partner, and Dr. Martens has also collaborated at times with smaller labels such as Engineered Garments. Recently, Dr. Martens teamed up with Vetements, one of fashion’s coolest labels of the past few years. Their special version of the 10-eyelet 1490 boot costs more than $600, and is currently sold out at Net-a-Porter, Barneys, and Nordstrom.

Dr. Martens as a sign of the times

You’ll notice that Campbell’s subcultural genealogy of Dr. Martens wearers, from mod and punk through Britpop, trails off in the early 2000s. Part of what changed is the decline of subcultures, which arguably don’t exist as they once did. There hasn’t really been a new music culture in the UK or US closely aligned with Dr. Martens since.

Grime, the UK’s homegrown answer to hip-hop, has some affinity for Docs, Campbell says. But really grime is all about sneakers when it comes to footwear.

So it’s difficult to parse exactly what makes a “fashion” or an “alternative” shopper at this point. Today, you’re as likely to see a pair of Docs on Miley Cyrus or Beyoncé’s backup dancers as you are on a goth or punk kid. You can buy a pair at Urban Outfitters, or on the designer fashion site Ssense, alongside labels such as Saint Laurent and Gucci.

Dr. Martens may be indicative of a bigger shift in how fashion works in youth culture today. Charlie Porter, the menswear critic of the Financial Times, talked about this change in a recent interview with Ssense:

In the time of punk, and in my time, as well, garments were a way you transmitted information about yourself and your interests—what you cared about, what you believed in…Clothing is no longer used in the same very simple, tribal way that I used it in my time. Now, it’s become much more complex in its role, so I actually think clothing has become more sophisticated. It’s not dumbed down—the messages that are being sent out are more sophisticated, and weirder, and more complex than just you’re goth, you’re this, you’re that.

Kids today are comfortable assembling their eclectic identities by pulling in references and ideas from a variety of places, just as their Instagram feeds do. Fashion today feels less defined by strict categories, such as “prep” or “punk.” As much as pointing to how the brand has grown, and how its image has shifted over the decades, Dr. Martens’ broadening customer base could be seen a symbol of this change as well.

There’s also another group of shoppers making Dr. Martens their own: women. The formidable boots can feel empowering, as Laura Craik writes for The Pool. She describes going shopping for a pair with her daughter, and all the 11-year-old girls wearing them on the playground at school, and recalls how she herself felt as a teenager, wearing her steel-toes: “I never thought of them as symbols of rebellion—they were just cool shoes. But they were cool in the best kind of way, aka by not trying to be cool at all.”

New frontiers

As it has opened up to a larger audience, Dr. Martens has expanded its range of products, too. It has ventured into footwear such as a “lite” line, which offers a similar look on a more pliant, lightweight sole. It sells leather slide sandals that still have Dr. Martens’ distinctive grooved soles but could be paired with, say, some Céline trousers. It makes tassel loafers.

But Dr. Martens’ key to staying relevant has actually been not to change too much. As far as those tassel loafers may be from Pete Townshend in Docs and a boiler suit, the core of Dr. Martens, both from a brand and a business point of view, remains its original styles. The original Dr. Martens boot brings in 48% of the company’s sales, Business of Fashion recently reported (paywall). Campbell says they’re careful not to mess around excessively with those core styles, or to stray too far into other kinds of footwear.

The company is very aware that it’s not a brand with easy avenues into other types of products. Right now, for example, Campbell notes that rubber pool slides are a big trend. “Easy money,” he says. “We refuse to do it.” It’s just not right for the brand, which wants to remain centered on that idea of “rebellious self-expression” that emerged decades ago.

The past few years have been very good for Dr. Martens—even despite its CEO recently departing. It’s a big turnaround from the company’s struggles in the late 1990s and early 2000s, when the brand overextended itself as it strived for fast growth. In 2002, amid flagging sales, it made the momentous decision to shutter its British factories and move manufacturing to China.

“They were struggling with addressing that transformation from what was essentially a family-owned manufacturing business focused on wholesale and turning it into a front-end branded business driving its own destiny with consumers directly,” Paul Mason, Dr. Martens’ current executive chairman, explained to Business of Fashion (paywall). Sales improved slowly, but they have really taken off since the private-equity firm Permira acquired the company in 2013.

Campbell has been with the brand for more than three years now, and says it has a strategy for sustainable growth that just didn’t exist before. ”If you think of particularly the last three years, some big decisions have been taken around brand management, and a lot of that is around distribution, about making sure that we’re selling the product in the right channels and that we’re targeting the right consumers,” he says.

The next goal is to make the brand as financially lucrative as it is culturally successful. Despite its outsized cachet, Dr. Martens isn’t all that big. In its most recent (pdf) fiscal year, its sales were £290 million ($384 million). By comparison, Timberland boot sales were $1.8 billion in 2016.

“The chapter that the brand is on now is very exciting because it’s almost like now trying to get the business to catch up to the brand,” Campbell explains. “What I mean by that is we have a brand which is known worldwide, has great affinity around the globe, and now we’re in a position where we’ve been able to really define and articulate strategies which will allow the brand to grow.”

The customers who’ll fuel this growth will include nostalgic or subculture-affiliated customers, yes, but it will also rely upon a ton of kids who probably couldn’t name a song by The Who and have never heard of Oi!—but think their 1460 boots look just right anyway.