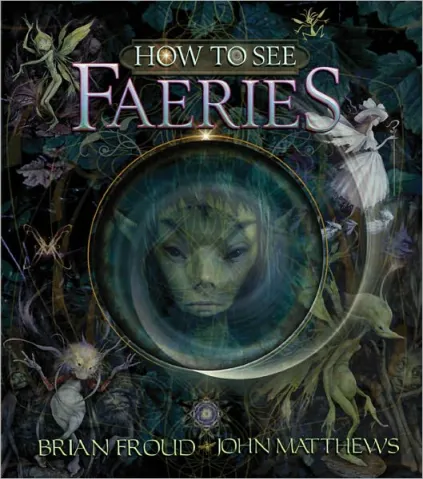

Here I combine a few excerpts from my interview with Brian Froud into a slightly longer but still rather short—and I hope wholly enjoyable—excerpt. Froud is exceptionally entertaining. Professionally, he worked with Jim Henson as conceptual designer for the films The Dark Crystal and Labyrinth. He has been a leading illustrator of fairies and many creatures magical and mystical, authoring or coauthoring an array of illustrated books including Faeries, The Faeries’ Oracle, How to See Faeries, and Brian Froud’s World of Faerie.

Brian Froud and his wife, Wendy Froud, a sculptor and puppet creator, live in Devon, England. You can learn more about their amazing projects and artwork at www.worldoffroud.com.

Their son, Toby Froud, played the baby in Labyrinth, and all three worked on 2019’s 10-episode prequel series from Netflix and The Jim Henson Company—The Dark Crystal: Age of Resistance—overseeing the puppets used in the series with Brian serving as primary concept artist and costumer, Wendy as fellow creature designer, and Toby as design supervisor.

Ray Hemachandra: When did you draw your first fairy, and how did that become a career?

Brian Froud: In college, I became interested in folk tales and fairy tales. Gradually I became more and more interested in the underlying meaning of it all and the possibility of the reality of real fairies. I discovered a book of fairy tales by Arthur Rackham. His pictures of trees with faces reminded me of how I felt about the world, how I felt that trees have souls and everything in the world does. I started to draw fairytale images. So I was sort of, in a sense, self-taught whilst at college.

I started studying as an artist, but I got fed up with the fact that you can paint terrible pictures and if you explain them in an erudite way it’s called great art. I thought this was rubbish.

I always believed that the picture itself should tell the story. So I then went and studied graphic design, because it seemed to me that advertising is more honest that way — the image actually has a function. But once I started on that, I realized that was really boring.

I graduated college around 1972, and it was a few more years until Alan Lee and I were asked to create the original book Faeries in 1977. That really just focused me in on fairies, and I haven’t stopped since.

Ray: And when you use the word “fairy,” that encompasses fairies, gnomes, sprites …

Ray: And when you use the word “fairy,” that encompasses fairies, gnomes, sprites …

Brian: Naming a fairy is notoriously difficult, because they don’t particularly like to be named.

There are so many of them, and humans have always wanted to categorize them. In that way, we think we can have more control over them.

So we’ve always called them by so many different names. But they’re always changing, so pinning them down is actually incredibly difficult. So, yes indeed, the word “fairy” does encompass all those things — gnomes and trolls and all the spiritual beings that are connected to the earth.

Ray: Are the English more open to the idea of fairies than Americans?

Brian: Not particularly. There’s just as much resistance there as all over. I suppose maybe Ireland is a bit more open.

Ray: Hold on, Brian — I apologize. The recorder stopped.

Brian: It’s the fairies!

Ray: How does contemporary society compare with earlier eras in terms of its engagement with the fantastical?

Brian: Well, the fantastical seems to have been, in earlier times, more mainstream. It was part of religious paintings. It might be depictions of hell, but they included spirits.

Spirits were seen to be very much part of the everyday world, and you were accosted by spirits all the time. It’s only really quite recently that we’ve relegated the fantastic as being just imagination and not real and having no purpose.

I feel that fantasy, the fantasy that I’m dealing with, is not a retreat from reality, but rather it’s a re-engagement with the world. I think we’re beginning to reapproach the fantastical in a proper way.

Ray: What’s causing that turn back to the imagination?

Ray: What’s causing that turn back to the imagination?

Brian: Probably the lack of imagination displayed everywhere else, in politics and other things. It seems to me that art has lost its connection to spirit.

Art always used to involve spirit. Painters painted spirit. They painted by commission things to go into churches, and that was painting spirit. Or they would paint people of wealth, and they would try to show how they had power, and again, this is sort of spirit.

It was only starting in the 20th century that artists decided they were the important thing — that the artist himself is the important thing and not the art, whereas this has never been so before. But we seem to be coming back into spirit via films, which are beginning to have more spiritual content, and also the people on the periphery, doing the sort of things that I do.

I’m in a peculiar world, because people always say that it is just fantasy and I make it up, or that it’s not art — my cool fairies on the edge of everything.

But gradually people are beginning to see it as art. Indeed, my art is now shown in museums. We’re bringing spirituality back into a world in which it has been lacking, and I think there’s a great need for it. We’re getting thirsty for it again.

Ray: You mentioned film as a medium that stirs the popular imagination. Would you talk about your work on The Dark Crystal and Labyrinth?

Brian: I had a job as an illustrator, and I wanted to change the direction of my work. I moved to the country, and immediately I started to paint fairies and trolls. Jim Henson saw one of my paintings on the cover of a book. He had in the back of his mind an idea for a film and asked me if I would define it.

He came to see me in Devon, England, and fell in love with the countryside there — the gnarled trees covered in moss, the beautiful rocks and streams. He said, “I want some of this feeling in the film.”

It was ironic that there I was finally painting the pictures I’d always wanted to paint and feeling very much at home in the countryside, and I ended up working in New York City, which is definitely the archetypal city. It was a small group of us working, and we just invented a whole world for The Dark Crystal.

I drew and drew and drew, filled sketchbooks full of drafts, and gradually we defined the look of the creatures. I built raw models, and then we started to build prototypes.

So the film itself grew slowly. We had the luxury of that. It took five years, from start to finish, of exploring the possibilities and literally creating a world. Then, near the end, we said, “Well, what’s the story we want to tell?”

We chose a mythic story that I think got misunderstood at the time. We weren’t trying to tell any big, dramatic new story. The Dark Crystal was supposed to feel like something that we’ve seen before or experienced before, as you do in myth.

It was a wonderful experience to work with Jim Henson. He was an extraordinary man.

Then, having said to myself, “Never, ever again,” Jim said, “Perhaps we can do another one?”

And I said, “Oh, why not?”

I came up with the idea of it being a labyrinth, and he said he wanted to put humans in it this time, and I said, “Well, what about a baby?” And I suddenly had this vision of a baby surrounded by goblins.

When I had finished designing, we had built the creatures, and we were about to film Labyrinth, my own baby was exactly the right age to play the part. So our son Toby became Toby in the film.

Ray: Brian, in Good Faeries, Bad Faeries, how did you decide who was good and who was bad?

Brian: That was — ooh — a very, very difficult thing. Again, there was so much resistance to the subject matter while trying to get the book published. Nobody wanted to publish a book about fairies; they said people wouldn’t be interested. Luckily, I discovered Lady Cottington and her pressed fairies, which revived a huge amount of interest in fairies, so I could go ahead and do the book I wanted to do, which was Good Faeries, Bad Faeries. They still resisted the word “fairies,” but as soon as I said bad fairies, everybody’s eyes lit up.

Part of what I feel is that the so-called bad fairies are really only there to get you to pay some attention. They trick you up until you’re lying flat on your back and you literally have another point of view. They’re about loosening up being rigid. They trip you over to break the barrier between you and the world. So their so-called “badness” actually can be quite instrumental in helping you with things.

It was hard for me to move forward, because I take responsibility for what I introduce into the world through my paintings. So to actually introduce something evil or bad was quite hard for me. Near the end, the editor at Simon & Schuster said, “You really need some more bad ones — and something really bad.” I said, “Like what?” and he said, “Well, death.” But death is not bad. Death is a transition.

The one I found most difficult to do was the Soul Shrinker. It must be one of my personal issues, because that’s the one I always pick out of the cards and I seem to have to deal with the most. We did the first seminar on the cards in The Faeries’ Oracle a few weeks ago. People opened the cards up and chose the one that they were going to have the most issues with, and interestingly, the Soul Shrinker was the one most people chose.

Ray: What does the Soul Shrinker represent?

Brian: It’s about rigid things. It’s about bad-mouthing people, saying terrible things about them. It’s about being locked into one way of thinking about things. It’s about intolerance. Intolerance breeds hate — for example, people killing each other in the name of religion.

To me, intolerance leads down a dreadful path that the world sometimes seems to be going to. So the Soul Shrinker is quite a difficult thing for me.

Ray: Have you encountered blocks to your work because of the subject matter of fairies?

Brian: I get it all the time. People just go blank when you say “fairies.”

I’ve been touring for years, coming out with books about fairies, and my wife, Wendy Froud, who is a doll maker, also did a book about fairies called A Midsummer Night’s Faery Tale.

We can never get any press coverage, because when you say the word “fairy” everybody has a preconceived idea of what that is. What it is is some sort of shallow, sparkly, tinselly, pink thing that has no power.

This is because we’ve relegated fairies to the nursery, and fairies were never there.

Fairies were always in the real world.

Fairies are difficult, tricksy creatures that we have to placate all the time. Now they’re coming back.

They’re sort of reminding us to pay attention to them and ultimately to pay attention to the world and our role in it.

We almost need another word for fairy, that’s the thing. Once people get to see what fairies’ real power is, then they understand.

Ray: Given the resistance to the subject matter of fairies, it must have taken some endurance and perseverance to stick with it.

Brian: Looking back, it seems like it was an incredibly brave act for me to do.

But once you step onto the fairy path, it’s almost like there’s no way off. You have to keep going.

However, in certain periods of doing that, the world was just saying, “You’re mad. Do something else. Why don’t you paint dragons?”

The world wasn’t supporting me in terms of finances, because nobody wanted this stuff.

So I don’t take credit for painting this stuff but rather for not giving in and giving up. I still somehow believed in it and kept going.

Now fairies are becoming much more popular. I see fairyland as this big sea, and the tide is sometimes out.

The tide is sweeping in now, and it seems to me that humans are becoming closer to fairies — that the barriers between fairies and humans are thinner now than they’ve been in a long time.

Ray: Would you describe where you live and how that impacts your work?

Brian: I live in the west country of England, on the edge of Dartmoor, which is a wild part of the country. It has moorlands and sunken trees. It has its mystique aspects, and there’s lots of folklore there. If anybody’s read Conan Doyle’s The Hound of the Baskervilles, that’s where it’s set.

I live in a traditional house, a thatched Devon lawn house. It was restored in 1690. It’s late medieval, but the foundations are probably Anglo-Saxon.

So I live in a house that’s incredibly old, and it’s typical that part of it is slightly in the ground. It’s very earthed. It’s almost like living in a hobbit house.

It is indeed that feeling of the medieval landscape around me that inspires me. There are tiny lanes that you can hardly get a car down with the tracks of ancient carts, and they’re all sort of sunken into the ground. I find it all very inspiring.

Ray: For people first encountering your work and engaging fairies, what surprises them the most?

Ray: For people first encountering your work and engaging fairies, what surprises them the most?

Brian: Lots of people say it’s like coming home. It’s a shock of recognition of how fairies truly are.

In the 20th century, artists did a great disservice to fairies. They painted fairies in a way that was shallow and trite. So when people see my stuff, they suddenly realize the depth of fairies.

The other day a man was handling the cards and said, “These cards are making me so happy and so sad.”

I said, “Goodness, why? Well, first, why happy?” He said, “It’s because they are taking me directly to the fairies.”

So I said, “Well, why sad?”

And he replied, “Because it’s taken me so long to get there.”

This excerpt is from an interview done for New Age Retailer magazine. I invite you to read and enjoy other interviews posted on this blog. Here are links to just a few of them:

- Byron Katie on questioning your thoughts and fearlessness

- Dr. Wayne W. Dyer on the law of attraction, cultural memes, and your purpose

- Life Loves You: interview excerpts with Louise Hay

- Sister Chan Khong on interbeing, service, and our little wars

- Eckhart Tolle on stress, the present moment, consciousness, and your awakening

- Interview with Doreen Virtue: excerpts from two of my interviews with the angel reader and teacher

- Marianne Williamson on the political obligations of spiritual people and on midlife

- Rabbi David Zeller on spirituality, religion, and the lessons of the Holocaust

I am actually 9 years old and I have been very close to fairies since I was little. I think my whole family was close to the…um…fairies when my baby brother was born in a tent! I have been researching

on some stuff too, I have talked to many spirits such as Jack Frost, Sand Man and other holiday spirits. I have also seen some of the Dark Crystal, and I loved the Labyrinth. I thought the article was great! And I think you really get the world of fairy. My Dad and I both think folklore is cool.

LikeLike