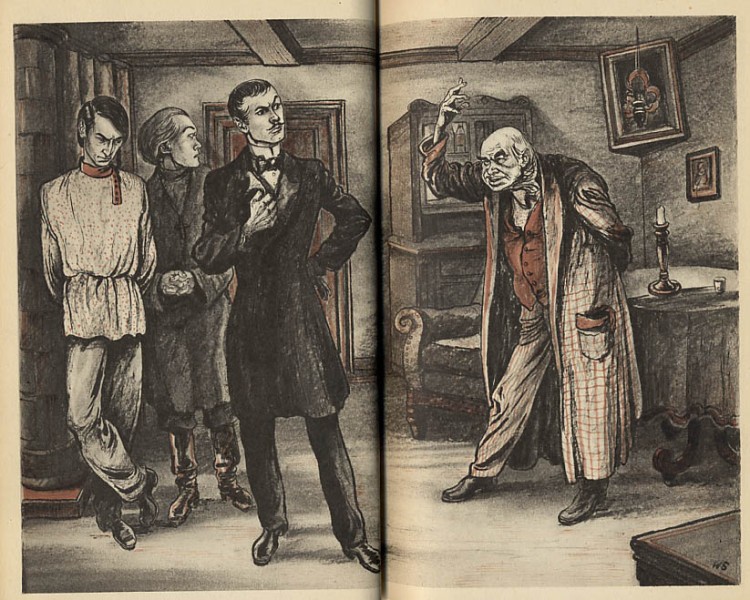

The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoevsky

My Rating: 5 of 5 Stars

I finished reading this book at precisely 0205 hours a week ago. The night still lay majestically over the impending dawn, and in its blackened stillness, swayed the echoes of this imperious book. The walls of my room, at once, turned into a fortress for Dostoevsky’s army of thoughts, and I, right in the middle of it, found myself besieged with its diverse, haphazard but mighty blizzard.

I am no stranger to this rambling Russian’s precocious visions and forbearance and yet, and yet, this work, swells much beyond even his own creator and spills over…. well, almost, everything.

A maniacal land-owner is murdered and one of his three sons is the prime suspect. Thus, ensues a murder trial and in its fold, fall hopelessly and completely, the lives of all the three brothers – the brothers Karamazov.

A life, when spans a trajectory both long and substantial, ends up writing a will that is both personal and universal. A notebook of reflections, a source of knowledge, an oasis of love and a mirror of perpetuity. And may I dare say that for D, this might well be a biography, which he, in his quintessential mercurial satire, chose to write himself, under the garb of fiction.

Dmitri, Ivan and Alyosha present the very tenets on which life gets lived, or even more, passed on. The impulsive and emotional Dmitri, the calculative and intelligent Ivan and the naïve and spiritual Alyosha represent the microcosm of a society which wagers war on the name of religion, status, power, values and ideals. And D takes each of these causes and drills, and drills, and drills even more, their various interpretations.

Religion, and church, take centre stage for a good 350 pages of this work. Amid homilies and confessions, monasteries and surrender, is pushed disturbing ideals that can rock one’s faith.

If you are surrounded by spiteful and callous people who do not want to listen to you, fall down before them and ask for their forgiveness, for the guilt is yours too, that they do not want to listen to you. And if you cannot speak with the embittered, serve them silently and in humility, never losing hope. And if everyone abandons you and drives you out by force, then, when, you are left alone fall down on the earth and kiss it and water it with your tears, and the earth will bring forth fruit from your tears, even though no one has seen or heard you in your solitude.

Aye, aye, I hear you, D and while some of it makes so much sense to my theist heart, some of it look outright suicidal. But why again, am I tempted to always, measure the righteousness, even lesser, the likeability, of my action from the perspective of my audience? Why make an ideal on a bed that doesn’t smell of my skin? I go to the board and think.

Philosophising, as he does with such ease and amiability, isn’t without unleashing a thundering dose of dichotomies. He steals the mirror from my room and turns it towards me: ‘Oh, so you believe in the good? How nice! But, well, then, how come the devil lurks in the dark corners of your room? No? You don’t agree with me? Oh where does all the cursing and ill-will spring from that you aim, with such precise ferocity, towards the people you don’t quite find to your liking? From where does all the impiety and malice, that you secretly drink with panache, emerge from leaving you intoxicated for hours, if not days?’ Sheepishly, I dig the chalk a little deeper into the board, and think.

And while I grope to find answers to his questions, I cheat and fall back on his treatise for hints, and insights.

You know, Lise, it’s terribly difficult for an offended man when everyone suddenly starts looking like his benefactor.

Why might a fallen man, a beggar, still keep a flame of dignity burning in his heart? Why might a harangued father, drive away his heirs from money, while spending his whole life hoarding for them? Why might a pauper, throw away his last penny on trifles, despite carrying a clear picture of his imminent doom in his eyes? Why might a pure heart, deliberately dirty his soul with pungent secrets, knowing there were no ways to erase them? Because deep down, what bind us, irrespective of our backgrounds, are the same threads: love, jealousy, ambition, hatred, revenge, repentance. In various forms, they dwell in us, and drive us, to give their formless matter, shape in different people, in different ways, at different places and in different times. I write a few words on the board and pause to ponder.

But, make no mistake; D turns the mirror on himself too and takes digs on his own character, because, after all, what life have we lived if we didn’t learn to laugh at ourselves? Laugh, yes; ah yes! There is plenty of humor ingrained, albeit surreptitiously, in this dense text and works like a lovely whiff of cardamom wafting over a cup of strong tea.

Ivan Fyodorovich, my most respectful son, allow me to order you to follow me!

There, I made a smiley on the board. I dropped the chalk and wondered: what created so much debate (and furore perhaps) when this book was first published in the 19th century? And then, I realized – even without my knowledge, my fingers had imparted two horns to the smiley’s rotund face. Yes, now that image surely needs to be questioned.

But do ask these questions. Do take the plunge into this deep sea of psychology and philosophy. Do feel the thuds of paradoxes and dualities on your soul. Do allow the unknown elements of orthodoxy and modernism to pucker your skin. Do allow some blood to trickle. Do allow some scars to heal. Because

No, gentlemen of the jury, they have their Hamlets, but so far we have only Karamazovs!”

That’s what!

[Image courtesy pinterest.com]

lovely review! I loved this novel. Dostoevsky was an amazing writer.

http://bookmagiclove.blogspot.com/

LikeLike