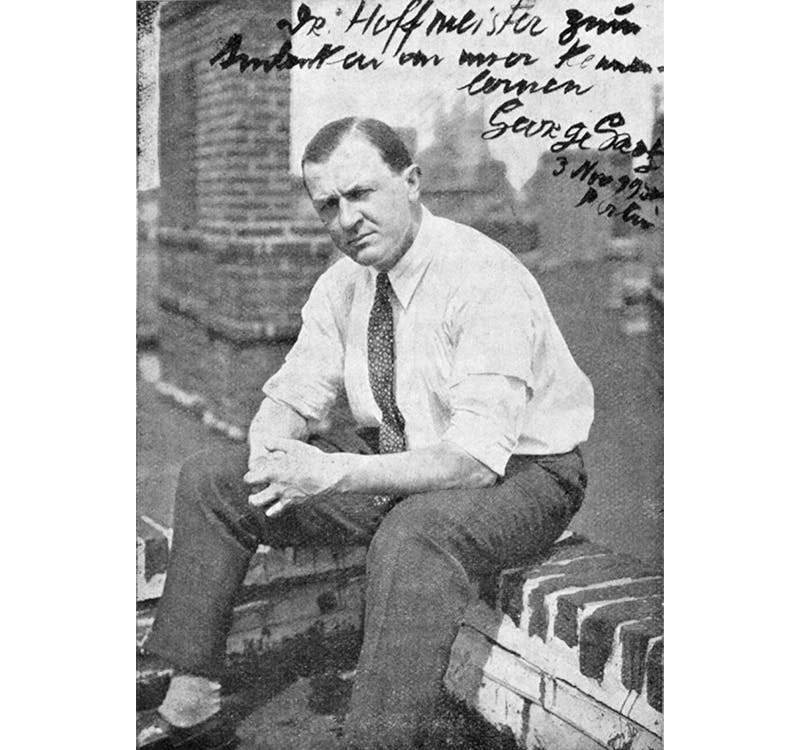

George Grosz: The Critical Caricaturist

Along with Otto Dix, George Grosz's critical eye saw the 'Golden Age' of the Weimar Republic for what it was.

George Grosz was born Georg Ehrenfried Groß on July 26, 1893 in Berlin. His parents were innkeepers, as documented in his works, where inns and bars often figured. In 1900 his father died and Georg moved with his mother to Stolp, Pomerania (known today as Słupsk, in Poland), where he attended school until he was fifteen. During these years he started showing great artistic talent and was encouraged to pursue art by his teacher.

Against his mother's wishes, he went to study at the Royal Saxon School of Applied Arts in Dresden from 1909 and at the School of Applied Arts in Berlin from 1912, where he completed his studies with a state diploma. In 1913 he went to Paris, where he was inspired by Japanese woodcuts and the realism of Toulouse-Lautrec. As he did in Berlin, Georg liked painting caricatures, which he based on the model of the satirical magazine Simplicissimus, sketching people in amusing places such as fairs.

World War I, experienced by him as 'horror, mutilation and destruction', as he later wrote in his autobiography A Little Yes and a Big No, made a strong impact on the development of Georg's work. Having been a soldier for a year, he became a strong opponent of the war. He began by drawing those wounded by the war and did not shy away from depicting the worst injuries. As a protest against the patriotism of the German Empire, from 1916 he called himself George Grosz.

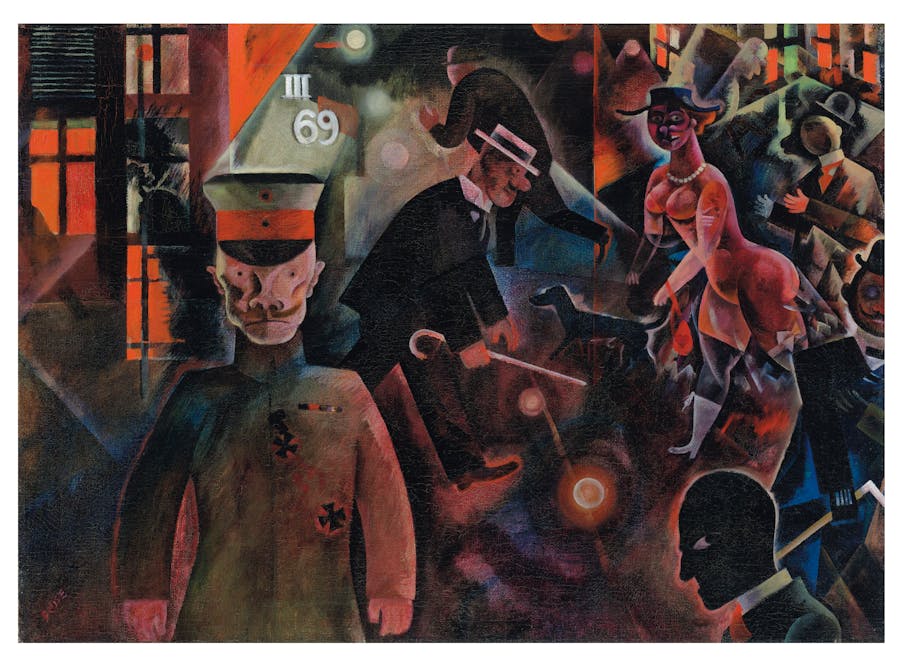

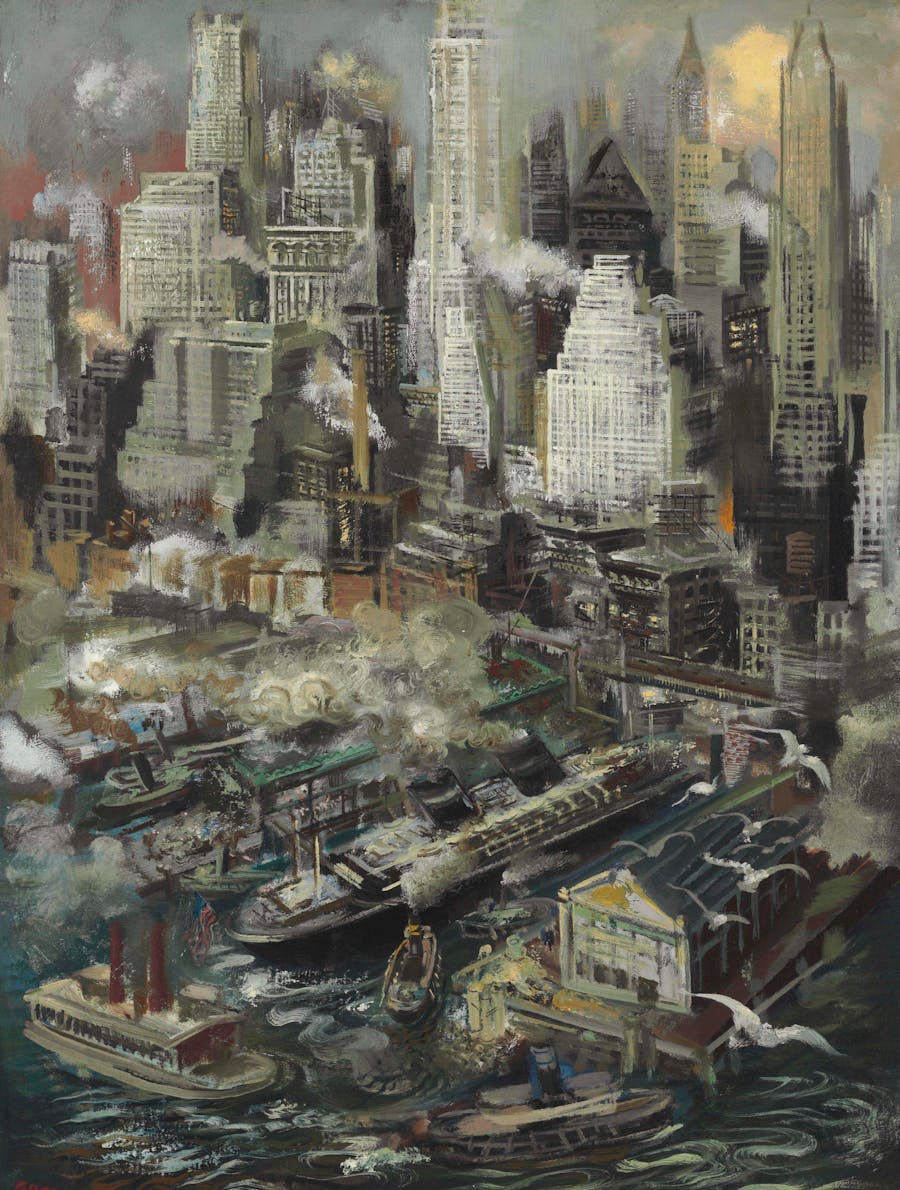

After being drafted into military service again and being discharged for unfitness for service, he returned to Berlin, which he found in a kind of apocalyptic state, as his work Metropolis details. He became a co-founder of the Berlin DADA scene, which was directed against the war throughout Europe with its often illogical art. During this period, his work shows surrealist, fauvist and cubist influences.

Related: The DADA Eccentricity of Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven

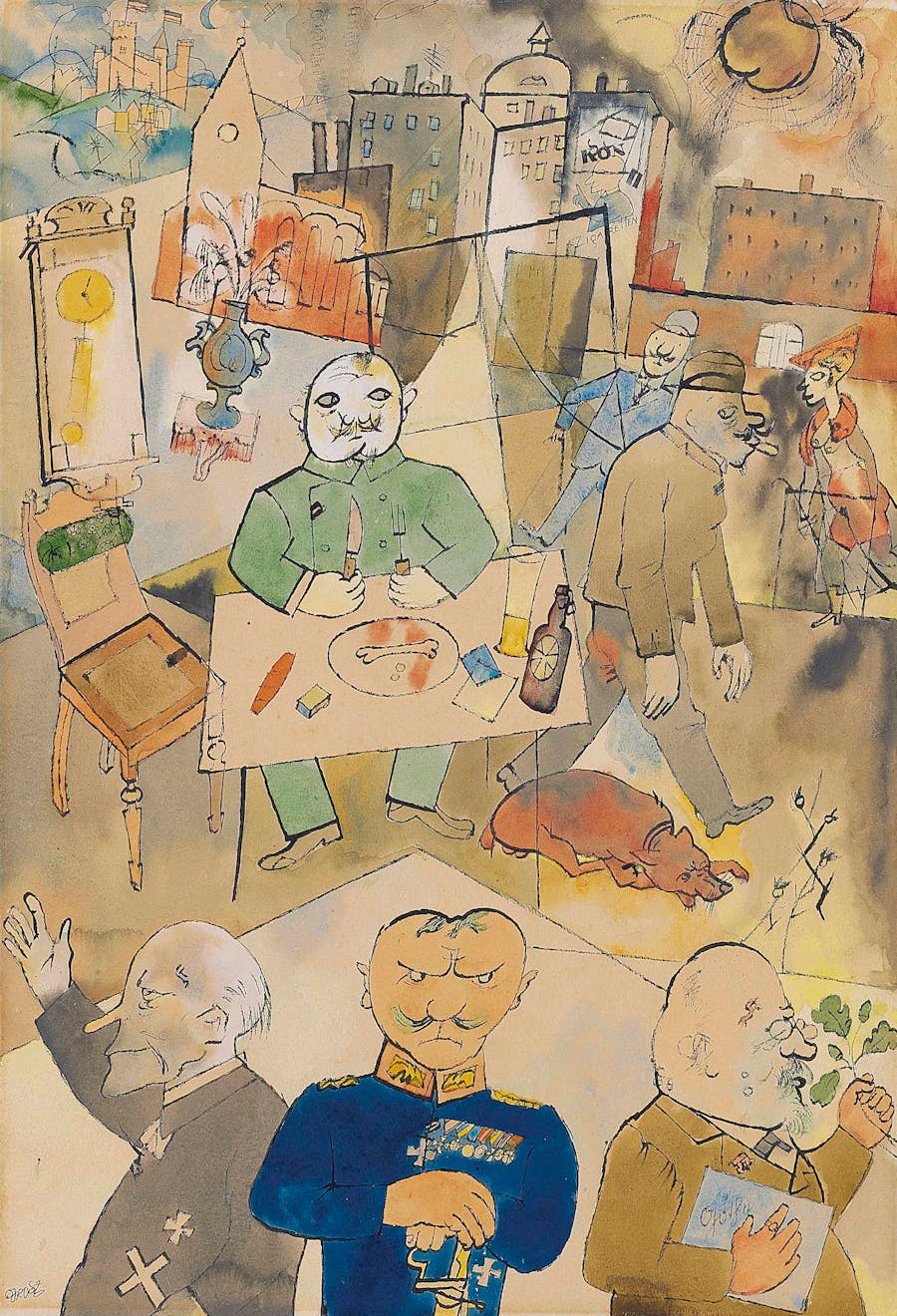

After the end of World War I, Grosz sympathized with communism and dedicated some of his work to his political views. However, a visit to the Soviet Union in 1922, during which he met both Lenin and Trotsky, changed his views, and he ended his three-year membership with the KPD.

From 1920, George lived in the Wilmersdorf district of Berlin after marrying Eva Louise Peter, with whom he had two sons. Having spent a long time with caricatures and illustrations, he returned to oil painting in 1925 and created another major work, Pillars of Society, which showed the first signs of the New Objectivity movement.

A successful phase began for Grosz with the gallery owner Alfred Flechtheim at his side. He received several awards and became a member of the Deutscher Künstlerbund in 1929.

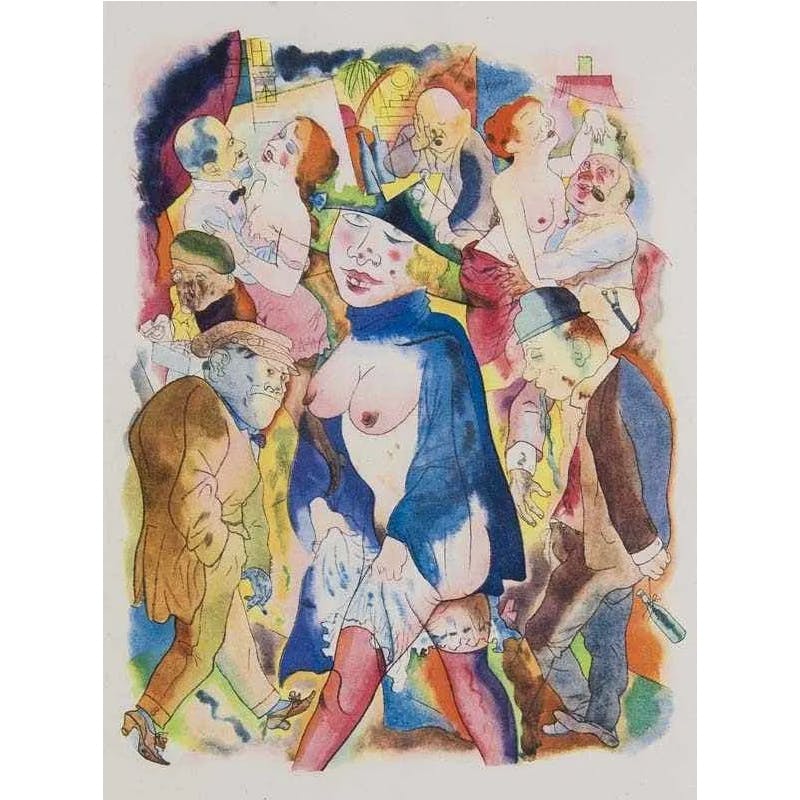

There was, however, friction with the authorities, who did not view Grosz's unsparingly critical works with benevolence. His portfolio Ecce Homo, published in 1923, even brought the artist to court because the works contained therein, created between 1915 and 1922, allegedly offended 'the sense of shame of normal people'. The pictures showed the indulgent hustle and bustle in the bars of the city and other establishments, mixed with depictions of mutilated soldiers returning home.

Related: The 10 Most Scandalous Artworks

In 1931 Grosz's financial situation deteriorated after his gallery owner Alfred Flechtheim terminated his contract due to his own financial difficulties. After Grosz spent a few months in the USA in 1932 to teach at the New York Art Students League, he emigrated there with his family in January 1933. The move came at the right time: his Berlin studio was soon after stormed by the new authorities, who classified his art as 'degenerate' and expatriated the artist.

Related: Hans Hofmann: Father of Abstract Expressionism

Faced with the Spanish Civil War and the terrifying developments in Germany, George Grosz resumed painting apocalyptic pictures. After the end of the war, his work became quieter and less political. He resumed teaching at the Art Students League and became again a successful artist, although not as much as in Germany before 1933.

In 1946 he published his autobiography, and often suffered with depression in his later years, which he tried to fight with alcohol. In 1959 he returned to his native city of Berlin, where he had been appointed a member of the Academy of Arts. He died there on July 6, 1959 after falling down a flight of stairs.

Today, his works sell for millions at auction. His current record was set in 2020 at Christie's with the $12.6 million sale of Gefährliche Straße.