Sonia Delaunay: Fine Art to Fashion

Inspired by vibrant color and abstract shape, Sonia Delaunay revolutionized the art world in the 20th century by co-founding the Orphism movement and fusing fine art and crafts.

Sonia Delaunay’s art oeuvre came out of the early 20th century, an era marked by dramatic change, instability and the advent of the modern. Her work was rooted in the expression of vibrant color and employed dynamic contrasts and the fluidity and abstraction of shape. Delaunay’s work was singular in that she deftly transcended the traditional definition of art, combining the painterly qualities and color vitality of her work into textiles, clothing, and home décor, blurring the lines between fine art and craft and ushering in a new representation of the modern woman.

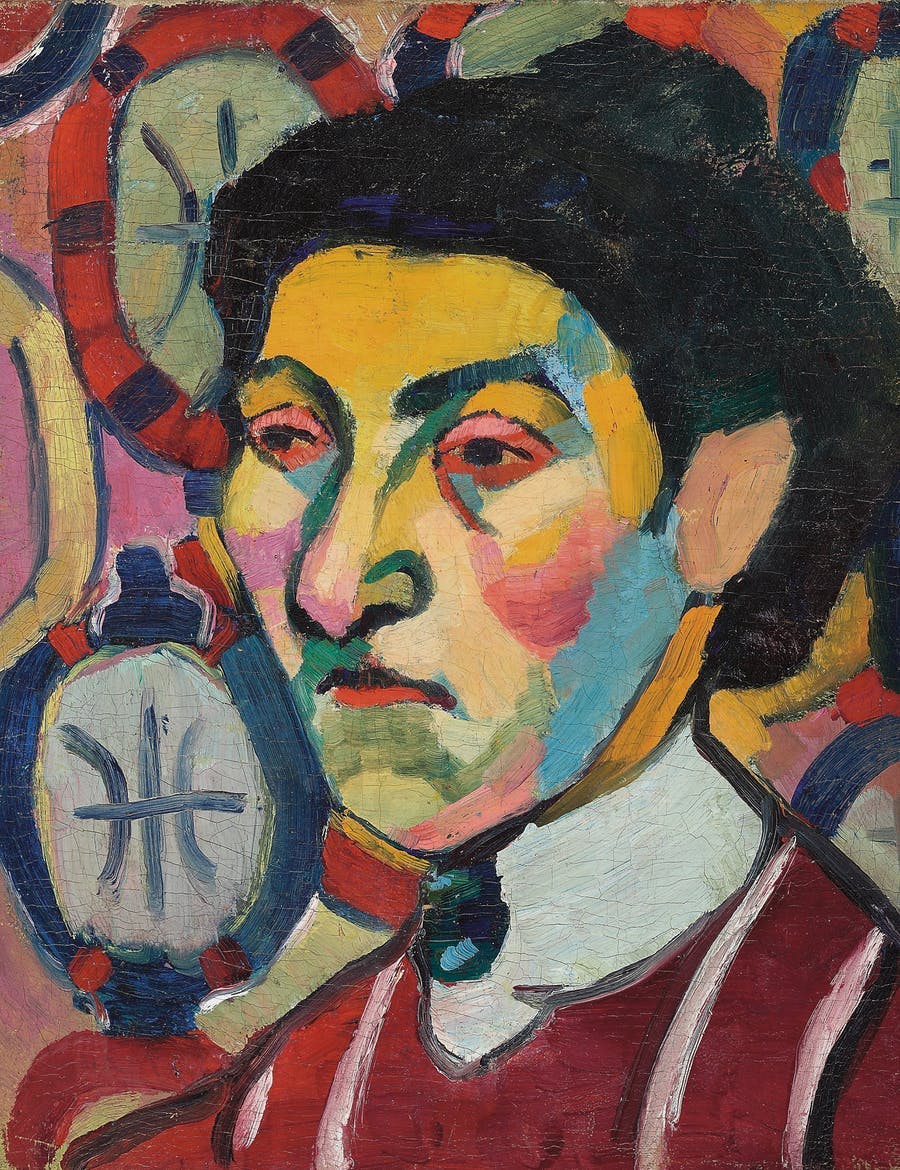

Born in 1885 in a wealthy household in Russia, Sonia Terk was adopted by her uncle and his wife and enjoyed an idyllic upbringing. Her talent for art was encouraged, and she studied at a prestigious school. She traveled to Germany and Paris in the earliest years of the 20th century where she was exposed to the works of Post Impressionists, which helped to cultivate her own painting style. After an unsuccessful first marriage, she married renowned artist Robert Delaunay, who was similarly inspired by color, light and shape, as well as the Post Impressionist and Cubist art movements.

Related: How Cubism Changed the World

The couple lived in Paris where they founded Orphism, an artistic movement that expressed the lyricism of color in artwork and was inspired by the Post Impressionist color palette and the Cubist manipulation of shape. Guillame Apollinaire, a French poet and good friend of the Delaunays, named the movement after Orpheus, the musician and poet found in Greek mythology to characterize the colorful poetry that the Delaunays evoked in their art. Orphism was based on fluidity of abstraction, less representation and the idea of simultaneity – putting bright colors next to each other to display powerful contrast.

Related: 12 Women Who Rocked the Art World

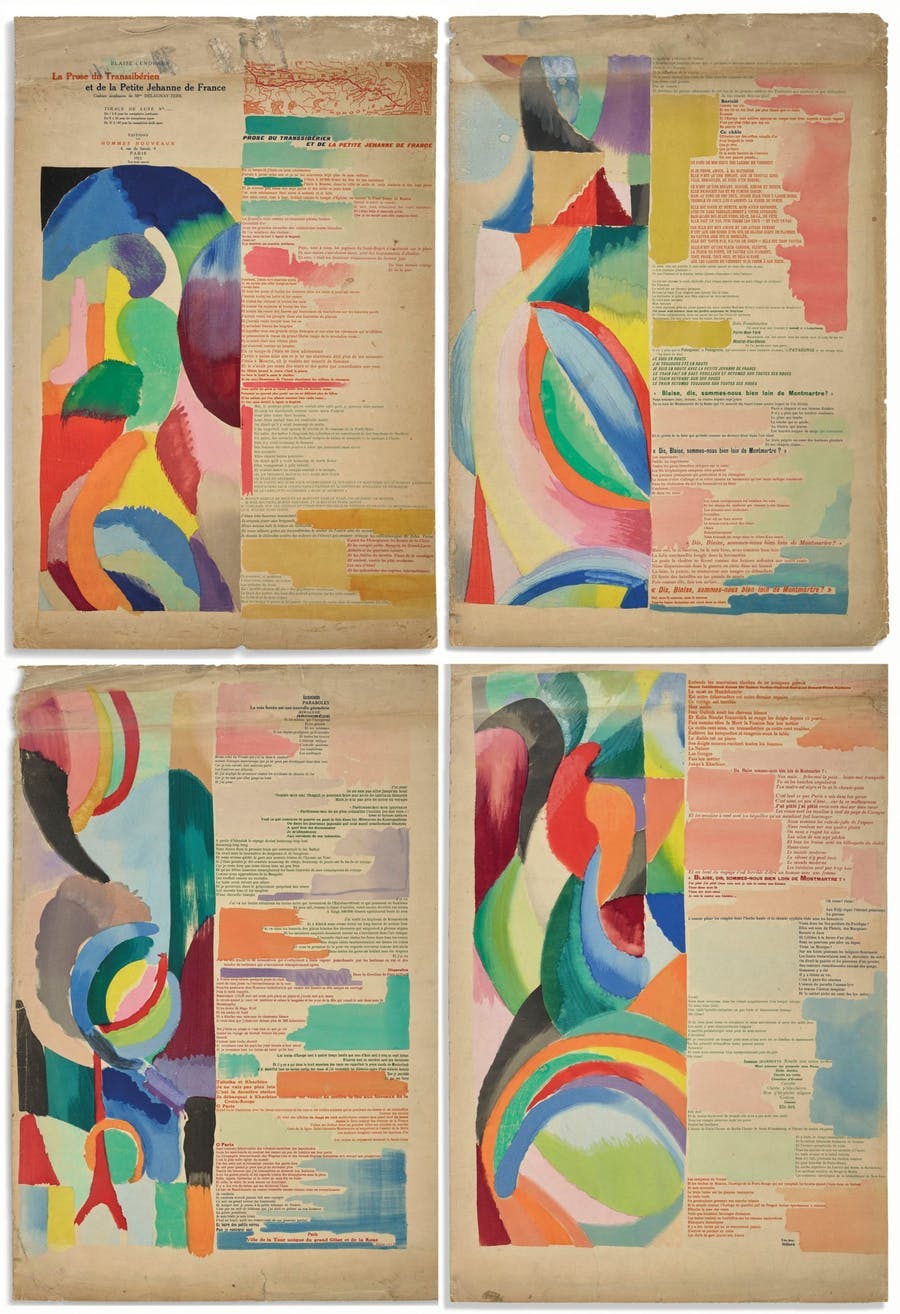

Sonia painted prolifically, but she came to widespread recognition when she illustrated a poem by Blaise Cendrars, a well-known Swiss writer and poet, who was also a close friend. The combination of poetry and art in this dual work embodied the idea of simultaneity, and Delaunay’s vibrant designs enhanced and gave richness to the text.

The Delaunays moved to Spain in 1914 where she painted often and even had a solo exhibition. In one of her dazzling paintings of flamenco singers and dancers in Spain, entitled Flamenco Singers (1916), Delaunay represents the figures of the dancer and a musician, yet she sets them almost as a background to her curvaceous shapes and the brilliant color. The figures almost become lost in the enveloping cycle of exciting color and form, displaying a focus on those elements rather than the people themselves.

Related: The Angel of the House to the New Lady: Women's Fashion in the 19th Century

In 1917, the Delaunays desperately needed money when the Russian Revolution ended the income that came from her family. Under these circumstances, Sonia Delaunay began to design costumes and clothing. Her first major commission was to create the costume for Cleopatra in the Ballet de Russes. With the popularity of her designs, Sonia Delaunay opened an atelier in Madrid where she dressed fashionable and forward-thinking women.

Related: Abstract Art: From Genre to Movement

Sonia Delaunay’s textiles and fashion strayed from classically feminine styles and introduced a look that corresponded to the modern concept of an autonomous, mobile woman. In a world shaken by World War I, women’s roles were changing and technology was growing at a rapid rate with the introduction of the motorcar and plane: symbols of movement, control and independence. Sonia's clothes employed the bold use of color and a more streamlined, boxy style of dress and jacket that suggested the new modern woman, one who was active and independent.

Sonia Delaunay’s design of Cleopatra’s costume for the Ballet de Russes exemplifies the modern woman aesthetic. As women enjoyed greater autonomy at this time than in the past, this costume was an an eschewal of traditional feminine roles, with its bright color, revealing cut and lavish embellishments.

Related: The 14 Most Expensive Female Artists

Upon her return to Paris in 1921, Sonia Delaunay continued her designs, having her colorful and abstract textiles turned into lampshades, hats, umbrellas, pillows and even cars, introducing the artistic atmosphere of the early 20th century to the public in a material way.

She also created more freedom and awareness for female artists and their unique struggle in the 20th century, and was opposed to the unjust separation of the work of male and female art. Curators often grouped the art of women together in shows or galleries, and she saw this part of the art world as denigrating to women as their art was not considered on par with men's. In 1964, Sonia was the the first woman to be a part of a retrospective show at the Louvre, which honored both her and her husband Robert.

Related: The Women’s Decade of Revenge

Sonia Delaunay in later years focused on smaller works, yet she always retained her love of bright color and shape. She made stencils called Color Rhythms, which were blocks of color placed next to one another, creating a simultaneous image, and later designed fashion sketches for French publisher Jacques Damase's book. She was awarded the French Legion of Honor in 1975, four years before her death at the age of 95 in 1979.

Her artwork contributed to redefining what art was by muddling the separation between fine art and craft, and she heralded in the look of the modern woman with her fresh designs that were reminiscent of her paintings. Being one of the first renowned female artists among an entirely male cohort of artists in Europe, Sonia Delaunay brought an innovative and creative outlook, redefining both modern art, the modern woman and attempting to upend the gender separation of artwork. Today her works frequently sell for six figure sums, with a record of nearly $2 million.