Wunderkammer: The Cabinet of Curiosities

Find out the fascinating history of the space known as the Cabinet of Curiosities.

Wunderkammer, from the German 'Wonder Rooms', refers to the 16th-century European phenomenon of creating spaces inside castles and aristocratic residences devoted to collecting and preserving singular objects. The 'curiosities' found inside these rooms could be anything from ancient finds to natural objects, religious relics, and works of art from distant lands. The creators of the wonder rooms sought to surround themselves with symbolic objects representing the world's extraordinariness.

There were essentially four kinds of curiosities in the collections: objects linked to the natural world, those that created by men, those that today we would define as technological and, finally, those linked to the sphere of the mystical. This ensemble gave rise to a new form of collecting compared to the medieval way of acquiring relics (to which the Wunderkammer was conceptually inspired). A new cultural tradition was initiated – the man of the 16th century had a cult: wonder.

Inside the Wunderkammer

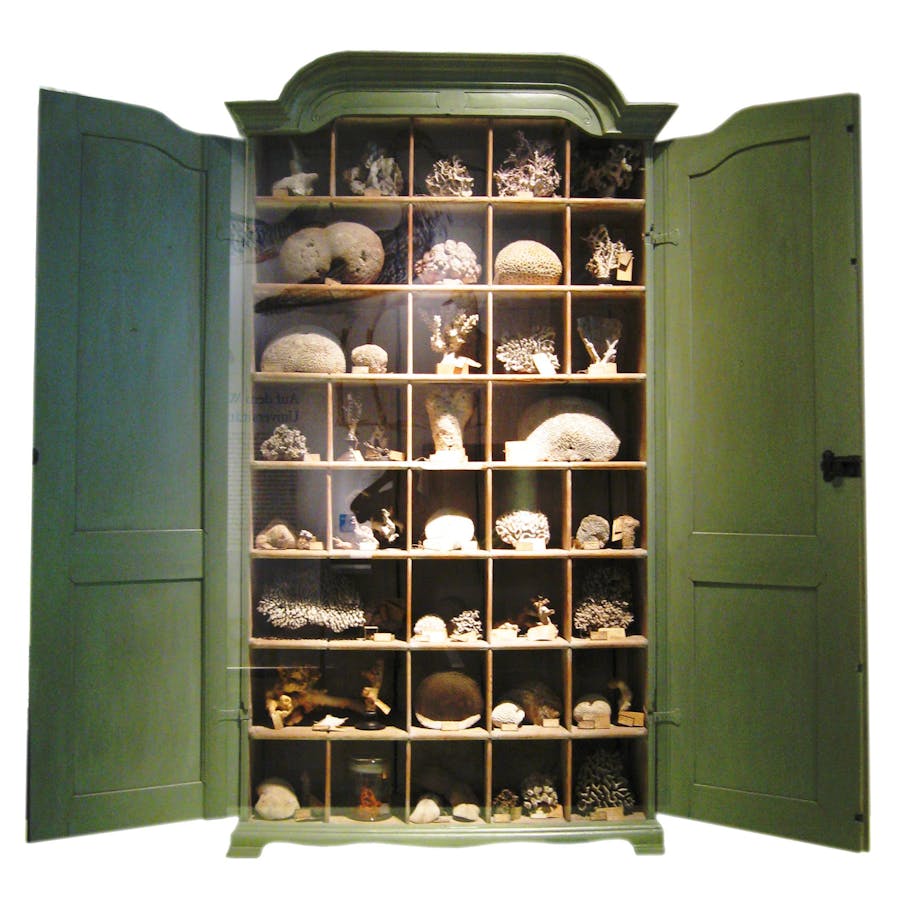

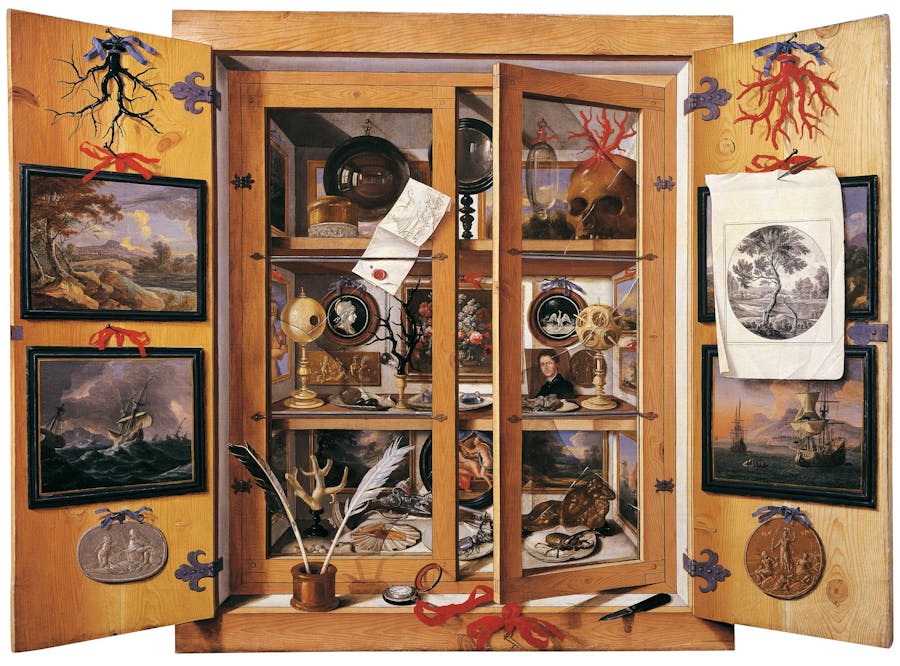

Typically, the Wunderkammer consisted of a fully furnished room, decorated on the walls and ceiling with paintings that suited the collector's taste. Displayed on the shelf of a glass cupboard, one could find an enormous shell, alongside dozens of other objects of different sizes, materials, and shapes such as spheres, snakeskins, eggs, corals, horns, bezoars. Also featured could be small mirrors with bone details, compasses, colorful feathers.

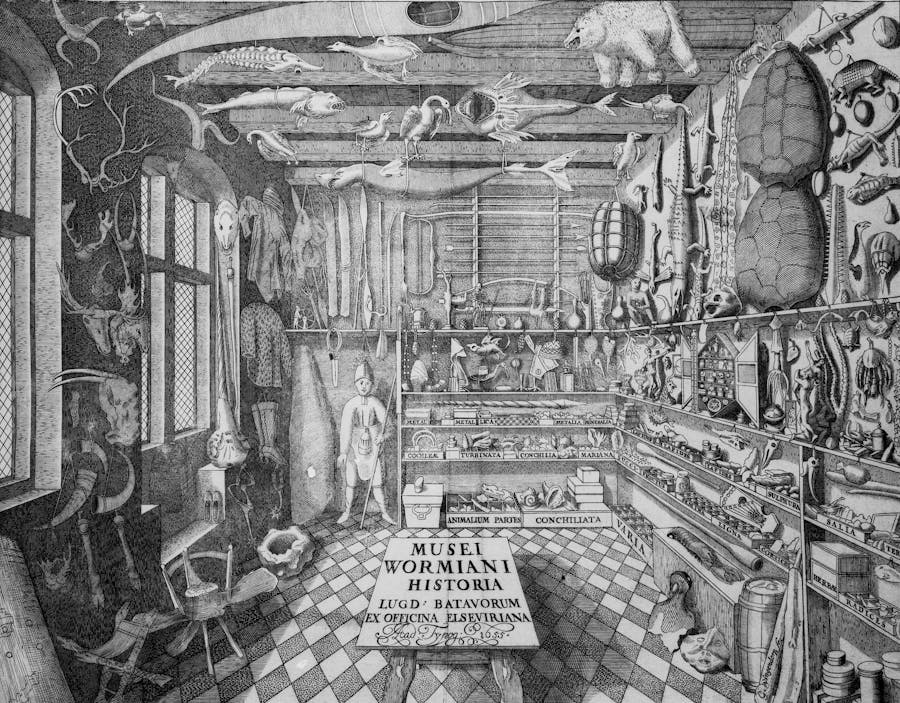

Those who owned a Wunderkammer wanted to fill the visitor's eye and leave no space bare. The studio of Francesco I de' Medici in Palazzo Vecchio, for example, had about twenty cupboards organized in the center of the room. In terms of arrangement, nothing was left to chance. The most impressive objects were left suspended in mid-air from the ceiling. Among these, the most common were stuffed crocodiles and other animal or plant creatures. Then there were the showcases, organized according to taxonomic or purely aesthetic criteria. These gave rise to compositions of shells, sometimes painted, juxtaposed with other natural objects or pieces of classical art. The idea behind the organization of a Wunderkammer was to create abrupt transitions of gaze from one object to another, thus constantly changing the scale of perception for an arresting effect.

Want to receive more articles like this straight to your inbox? Subscribe to our free newsletter!

An interesting fact concerns the preservation of Naturalia, i.e. objects of natural origin. To prevent degradation over time, favorite items were selected, including plants and animals that could be easily dried or subjected to archaic taxidermy experiments – as was the case with crocodiles, fish, small mammals, plants and fragments such as bones and teeth.

Aristocratic and Humanist Wunderkammer

The ancestor of the Wunderkammer is the 'Studiolo', a space devoted to studying conceived by the noble and wealthy such as Charles VI of France, Jean de Berry, or the Medici family in Italy. In the 16th century, the most prestigious Wunderkammer belonged to the wealthiest: by collecting rarities, the royal classes made their power tangible, highlighting their connection to distant worlds and lands.

Something changed, however, towards the middle of the century. Alongside the aristocracy's Wunderkammer, another one developed: that of the humanists, who collected objects needed for scientific research, such as plants, animals, or minerals. This happened following a real cultural earthquake, triggered by the discovery of the 'New World', i.e. America, which renewed humankind's curiosity to know more about the world.

Among the best-known names of naturalists and botanists who created famous Wunderkammer was Ulisse Aldrovandi (Bologna, 1522), who housed a collection of naturalia in his own home of around 17,000 objects including crocodiles, puffer fish, and snakes, which are today kept in the University of Bologna, in Palazzo Poggi. Aldrovandi wanted to document, study, draw, and publicize the variety of nature. Aldrovandi is also remembered for the publication of works such as 'Serpentum et Draconum', 1640, volumes of rare and peculiar specimens he'd studied in great detail.

Another famous example is the Settala Wunderkammer, created by Manfredo Settala, a Milanese scientist who – following several journeys in the second decade of the 17th century – created a collection of around 3,000 objects, catalogued by Settala himself into Naturalia, Artificialia, and Curiosa, i.e. objects considered outside the norm. Today, the Settala collection is housed in three different institutions: the Pinacoteca Ambrosiana, the Mudec, and the Castello Sforzesco in Milan. Looking at some old illustrations depicting the original Wunderkammer, it was organized in one large room, with the objects arranged inside cabinets with drawers and small showcases in the lower part, and others hung on the walls in the upper part.

The most sought after Naturalia and Artificialia

Stuffed crocodiles were considered the most valuable naturalia and were therefore very common in the Wunderkammer. The choice was a reference to the medieval custom of keeping them inside churches: their monstrous appearance, displayed in mid-air, 'cancelled' their diabolic power in the sanctuary. The theme of the macabre and of death, which had defined taste since ancient times, exploded with the Wunderkammer.

Artificialia were the most desired objects in a Wunderkammer. These were artistic objects, obtained by working with precious materials of natural origin. One of these is the Nautilus Shell, known since antiquity for its proportions that follow those of the golden ratio. Also widely used in goldsmithing, the shell has a smooth white surface with orange-red streaks and can reach a size of about 20 centimeters in diameter. Collectors wished to own specimens decorated with small pictorial representations or gold plating. The point was to blur the line between art and nature, as happened with the decorated shells, but also with corals and ivories.

Do you own any interesting design pieces? Get them valued with ValueMyStuff!

An object's desirability depended on the myths and legends around it. The Narwhal, a cetacean from the Arctic Ocean, was, for example, attributed the magical power of a unicorn because of its horn/tooth, a long twisted spiral up to 3 meters long in male specimens. For a collector, owning a Narwhal tooth was a cultural signifier.

It might be difficult, in the age of over-information, to fully understand the feeling of awe and longing for the mysteries of the world that inspired Wunderkammer. At the end of the 17th century, the sciences had progressed to such an extent that it became impossible for men to believe, as in the 1500s, that they were dealing with a dragon's tooth and not a shark's, for example. Objects that until a few decades before held a predominant role in the Wonder Rooms slowly lost their power to arouse that feeling of wonder. Mermaids, unicorns and odalisques became mere 'curiosities' and the term Wunderkammer was thus transformed into 'Cabinet de Curiosités'.

The Wunderkammer and the birth of the Modern Museum

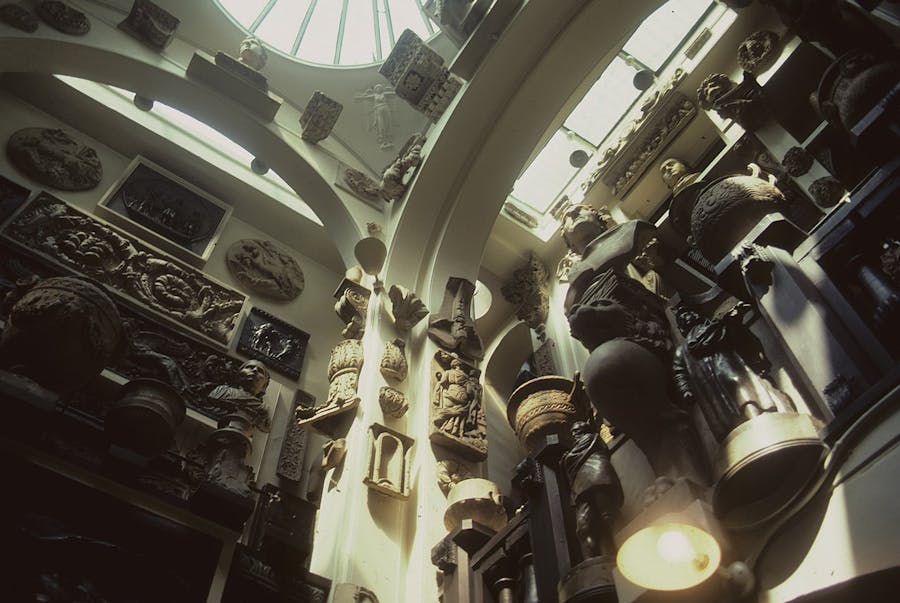

The spirit of the modern museum owes its origin to the Wunderkammer and its role as a custodian of objects and place of intellectual adventure. The collection of Sir John Soane's Museum, in London, was one of the first to open to the public. Still open to visitors today, what is now a small museum was founded in the 19th century as the home of Sir John Soane, a famous neoclassical architect who had a strong passion for collecting works of art.

Related: 8 Must-see Design Museums Around the World

Guiding the design of the building was the principle that, like the Wunderkammer, the rooms should celebrate Soane's life and at the same time house the collection of his drawings – around 30,000 of them.

The setting in which the marble bust of Sir John Soane himself is displayed is significant: positioned between two small statues portraying Raphael and Michelangelo, it suggests that he considered himself an heir to the great artistic tradition of the Renaissance. The mixture of antiquities, furniture, sculptures, architectural models, drawings and paintings – including works by Hogarth, Turner and Canaletto - must have had a striking effect on the visitor.

In 1883, Soane donated the collection to the state on the condition that it would become a museum after his death. The identity and purpose of the collection then changed drastically: from being a private space for the preservation and contemplation of objects, it became a public institution, one among many that today makes us wonder.