The entrance into Bruce Nauman’s exhibition Neon Corridors Rooms at Pirelli Hangar Bicocca inevitably passes through his studio. In the second half of the 1960s, it was in this very place that we can imagine Nauman, young and without means, struggling with a nearly empty space. Working for long and long hours, he found himself dealing with the concept of artistic work and the space of creation, ultimately arriving to face himself: “If I was an artist, and I was in the studio, then whatever I was doing in the studio must be art.”

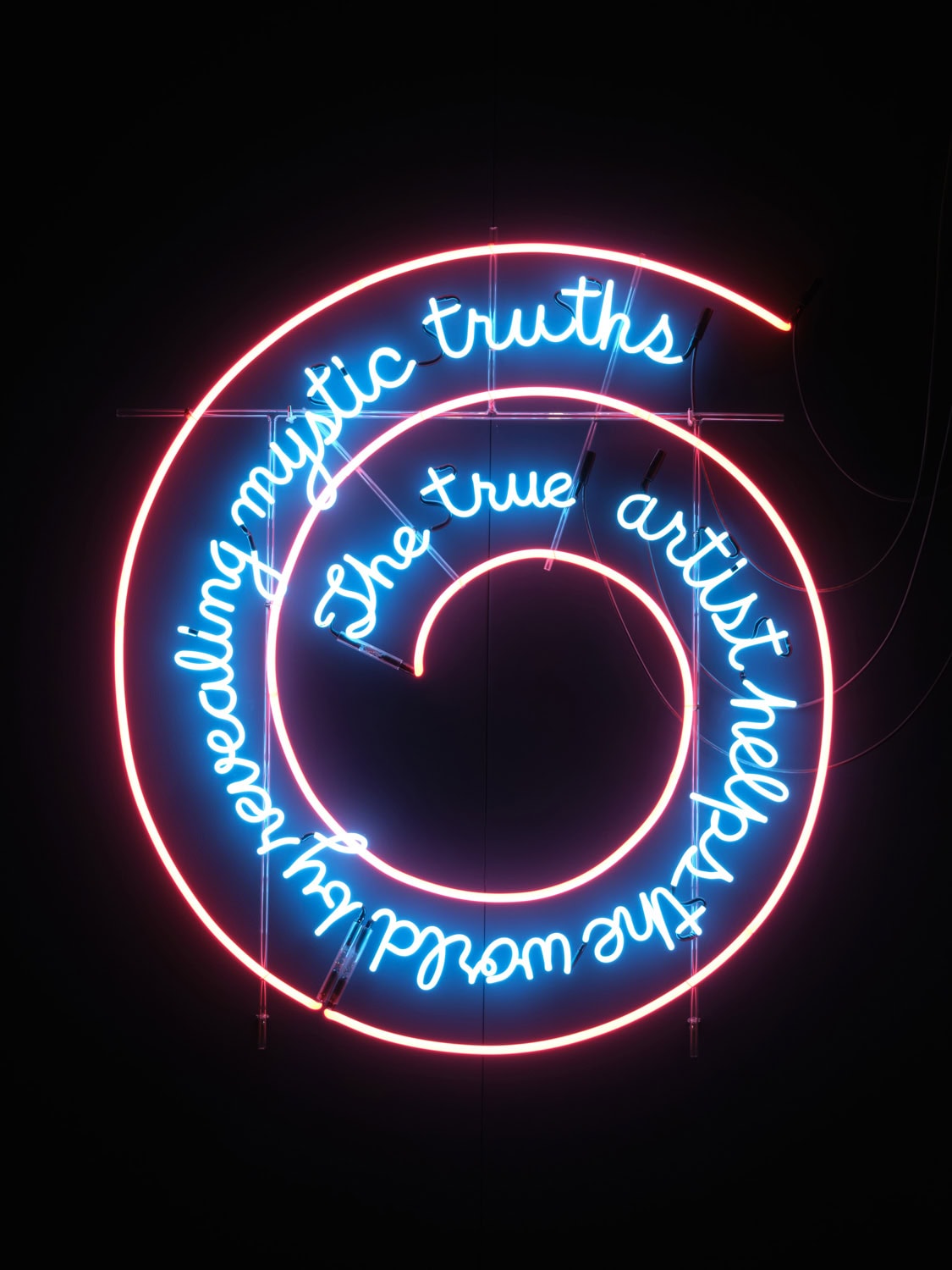

This syllogism penetrated strongly into his artistic practice, which from that moment expanded to cover almost every media, merging with another great realization of his role and work, which is summarized in one of his most famous neon works: The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truths (1967).

This neon spiral is among the very first works that meet in the exhibition and forces us from the first moments—as suggested by the curator Andrea Lissoni—to do a “mental movement” to be read and understood; summarising an approach that the public will have to use throughout the whole exhibition. It is precisely the audience that from the very first moments has become one of the fundamental elements of Nauman’s artistic equation.

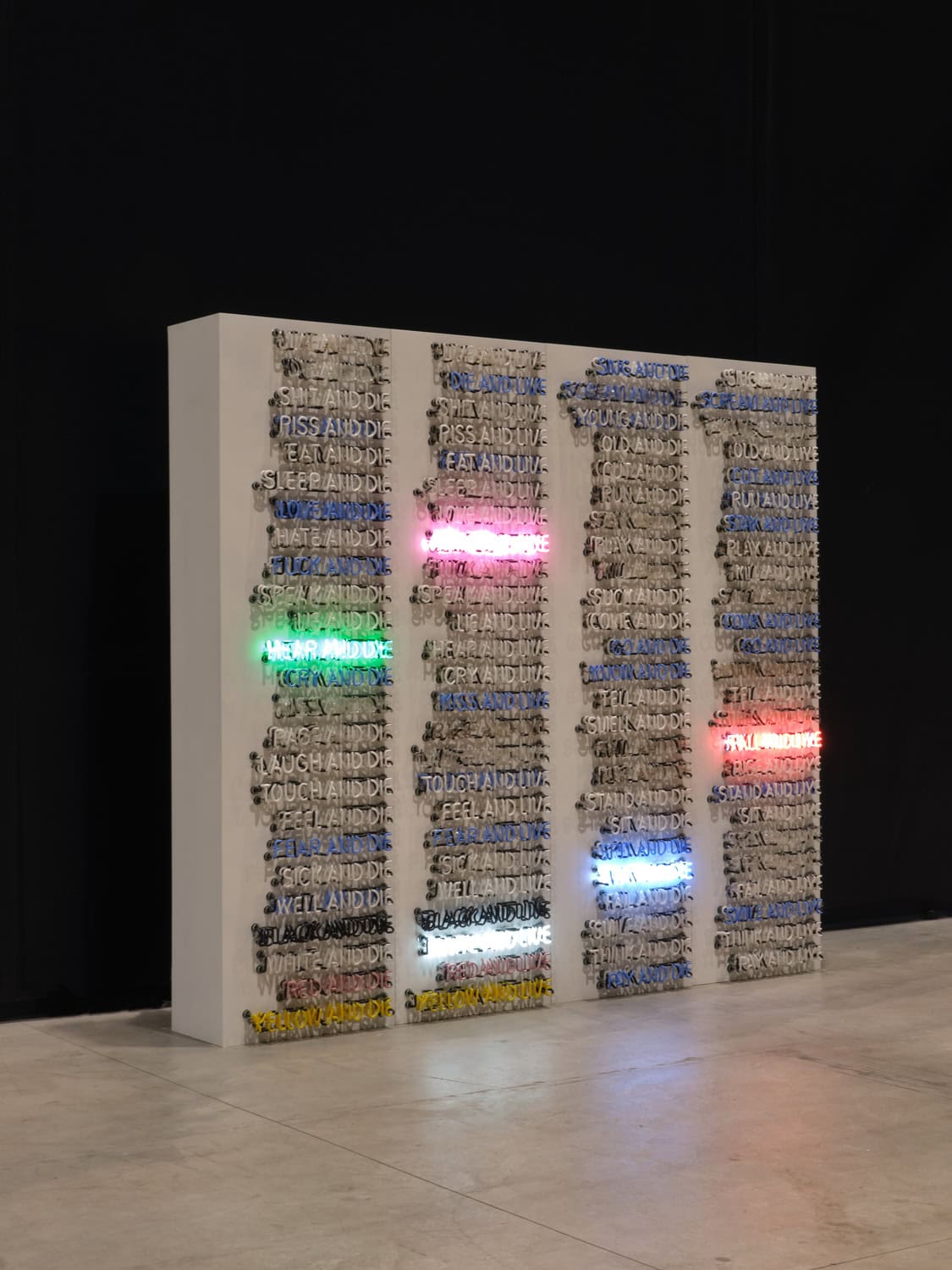

The movement characterizes not only the intellectual aspect of the exhibition but first and foremost the physical and spatial one: the entire exhibition becomes a space to explore, spanning more than forty years of Nauman’s artistic production. The exhibition—organized in collaboration with Tate Modern of London and Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam—presents thirty works created since the sixties, bringing together for the first time in a single exhibition the various types of corridors and rooms produced by the American artist, as well as a series of historical neon works including the masterpiece One Hundred Live and Die (1984).

As we pass through the exhibition and the works presented, we can sense the choreographic work Nauman engages with his audience: we find ourselves forced and disoriented between narrow walls and sudden openings, chasing voices and images along spaces poised between the physical and the psychological. These corridors, as one can guess from their appearance, were born as props; the first created as the setting for the video Walking with Contrapposto (1968) and becoming a stand-alone work in the following year with the title Performance Corridor. Their exterior appearance of scenic objects and their eerie and disorienting interiors convey a feeling that internet culture would associate with what are called backrooms: existential places, empty and disconcerting.

The last corridor, both chronologically and spatially, is the one created by the work Raw Materials (2004), with its 21 speakers that accompany the visitor to the exit, in a parallel route to the central exhibiting space. The work was created as a site-specific installation for the Turbine Hall of the Tate Modern, with the aim of creating a space, a corridor, using sound. A space that contained a retrospective of his work, having been created entirely using the sound part of his previous works, and it is even more significant to walk along it in parallel with the other great anthological exhibition that has just been visited; leaving behind the last audio track in which you hear Nauman shouting in loop “Thank you!, thank you!, thank you!”