Audio only:

In this episode Trent examines the arguments Catholics make in favor and against the use of nuclear weapons in World War II against the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Transcript:

Welcome to The Counsel of Trent Podcast, a production of Catholic Answers.

Trent Horn:

Hey, everyone. Welcome to the Counsel of Trent Podcast. I’m your host, Catholic Answers’ apologist Trent Horn.

It’s been nearly 80 years since the United States dropped two atomic bombs on Japan during the end of World War II. Those would be the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In today’s episode, I want to talk about whether this action was moral or whether it was gravely immoral, and that’s still controversial among many Catholics, but before I do that, I hope you’ll like this video. Subscribe to our channel and support us at trenthornpodcast.com. No jokes about that because, well, today’s topic is pretty grim. Let’s put out some facts about the bombings, and then I’ll give a moral analysis.

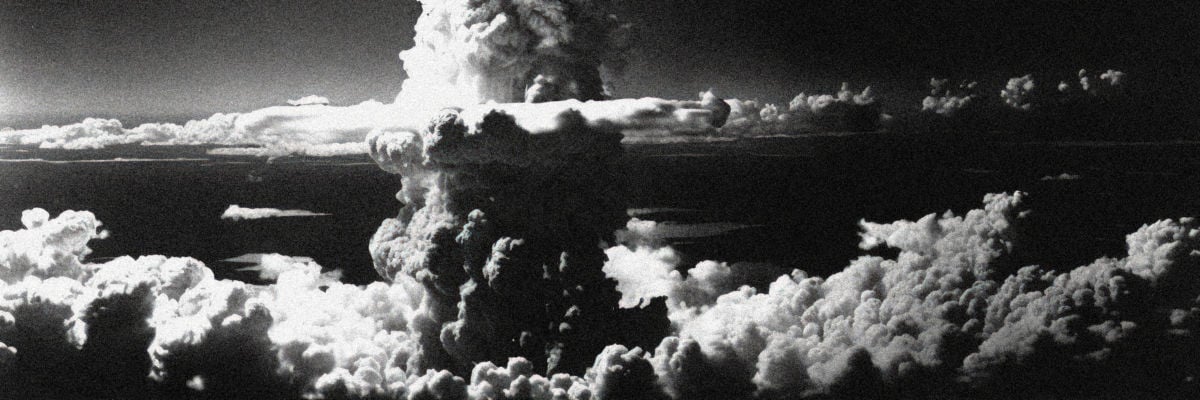

On August 6th and 9th, 1945, the United States detonated two atomic bombs over the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, respectively. The bombings killed between 129,226 people, most of whom were civilians. It’s the only use of nuclear weapons in an armed conflict. Japan surrendered to the allies on August 15th, six days after the bombing of Nagasaki.

This reenactment from the BBC does a good job of dramatizing the bombing itself and showing how the bomb exploded in the air over the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki to cause maximum damage. About half of the victims were killed during the first day of the bombing, and the rest died of burns, infections and radiation poisoning over the next few months. Here’s how one survivor of the bombing describes the aftermath.

Speaker 3:

The saw things no person should witness.

Speaker 4:

There were already a number of people that were dead along the roadside. People were burned, suffering and begging for a drink of water. Some of the injuries were so severe that, for example, people with burns, their skins would be dripping from their bodies. Some of the people actually had broken limbs protruding. When we came back after the surrender, we came back to the same area, and the whole city was completely flat. It was really devastating to see.

Trent Horn:

Catholics tend to hold one of two positions on this issue. Recent popes, like Francis, Benedict, and John Paul II have condemned the bombings and have often prayed at the sight of the attacks when they visit Japan. Catholic theologians who criticize the bombings cite St. Paul’s condemnation of the idea that we can do evil that good may come. That’s in Romans 8:3, and the Second Vatican Council, which says, “Any act of war aimed indiscriminately at the destruction of entire cities of extensive areas along with their population is a crime against God and man himself. It merits unequivocal and unhesitating condemnation.” The argument on the other side of the debate is that the atomic bombings were necessary to prevent a greater loss of life that would’ve resulted from the allies invading the Japanese mainland.

Father Wilson Miscamble offers the standard defense of that argument in this video from Prager University.

Father Wilson Miscamble:

The judgment of history is clear and unambiguous. The atomic bombs shortened the war, averted the need for a land invasion, saved countless more lives on both sides of the blood-soaked conflict than they cost and ended the Japanese brutalization of the conquered peoples of Asia. Given the alternatives, what would any moral person have done in Truman’s position?

Trent Horn:

Who’s right? I side with Catholic philosophers like Father John Ford, Elizabeth Anscombe and Edward Feser, along with the popes and the magisterium, who say the bombings were not justified because morality does not allow us to do something that is intrinsically evil in order to achieve a good end or prevent a greater evil. Morality allows us to cause bad things to happen under limited circumstances, but it doesn’t let us commit intrinsic evils.

For example, it’s not wrong to bomb an enemy radar station in the middle of the night even if you know a civilian at the station like a janitor will probably be killed. You don’t intend the innocent man’s death, and you’d be relieved if you found out he just didn’t show up to work that night, but you can’t intentionally target civilians in a war for the purpose of using their deaths for some greater good. If we say the bombings were justified because they produced the best consequence overall, then we’ve entered the realm of consequentialist morality, specifically utilitarian morality.

Father Wilson Miscamble:

Truman’s use of the bomb should be seen as his choosing the least awful of the options available to him.

Trent Horn:

If your moral standards boil down to supporting whatever action produces the best outcome, then you’ll abandon the idea of intrinsic evils or actions that can never be done no matter the consequences. Catholics understand this when it comes to abortion, but often fail to apply it to war.

For example, I don’t understand Catholics who say you cannot directly kill a child through abortion even to save the mother’s life, but you can use atomic bombs to save soldiers’ lives. When it comes to abortion, they’ll say that, even if both mother and child will die if no abortion is performed, you still can’t perform the abortion. Even if you have a choice where two people will die and another choice where only one person dies, you can’t pick the one person if that choice requires directly killing an innocent person, but then some of those same Catholics will say the atomic bombs were justified because it was the only way to prevent more people from dying in an invasion of Japan.

They say there was one choice where many people die and another choice where fewer people die, so they simply choose the one where fewer people die even though that choice involves directly killing innocent people. You can’t kill, directly kill, an unborn child even to save his mother’s life. You can’t directly kill the mother to save the child, but apparently, from their perspective, you could kill many unborn children through an atomic bomb, I’m sure many did die, to save many soldiers’ lives. It just doesn’t make sense.

If you embrace this consequentialist morality, by the way, you also lose the ability to call anything a war crime because a military could always say, yeah, that was bad, but we were just trying to save lives by ending the war sooner. This could be things like exclusively targeting civilian populations or centers like hospitals or preschools, torturing prisoners of war to get information or to pressure the enemy to surrender, purposely destroying religious or cultural artifacts to reduce enemy morale. The list goes on.

The United Nations says that, “One kind of war crime includes intentionally directing attacks against the civilian population as such or against individual civilians not taking direct part in hostilities.” we’re better at recognizing war crimes when they’re committed against us. For example, imagine if the Nazis had dropped an atomic bomb on Pittsburgh. Would we have considered that just another battle in the war that was meant to hinder our steel production or would we have called it a war crime that was meant to terrorize American citizens?

Here’s two other examples from the conflict with Japan. Between 1944 and 1945, Japan sent a thousand balloon bombs into the jet stream with the goal of starting forest fires in the US and causing panic. Now, the US Office of Censorship was aware of the bombs’ panic-inducing potential and concealed news reports about them exploding on American soil. Fortunately, the bombs did not cause widespread destruction, but one that landed in Oregon killed the pregnant wife of a local minister and five of her Sunday school students. They were the only American civilian casualties in the continental United States during World War II.

Speaker 6:

Over a thousand were launched. They went as far as Texas and, as long as they stayed airborne, they could carry great distances. Depending on the wind and the altitude they maintained, they were falling all over Western America.

Speaker 7:

He heard her exclaim, “Look what we found,” and seconds later, by the time he got up there, his wife, who was pregnant at the time and only 26 years old, and his five children were dead…

Speaker 8:

It’s tragic to think just how unlucky this family was…

Speaker 7:

… the only known deaths in the Continental United States caused by the enemy during World War II.

Speaker 8:

… the wrong place, the wrong time and the innocent curiosity that went horribly wrong.

Trent Horn:

Do you feel that it was wrong for the Japanese to send a bomb over to the US for the sole purpose of causing fear, widespread destruction like forest fires among civilians? If so, then you should probably be against the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Here’s something that could have happened in the US if Japan had not surrendered in August. In 1945, the Japanese surgeon general, Shiro Ishii, planned to release balloons and bombs carrying plague-infected fleas over California coastal cities in an attack called Operation Cherry Blossoms at Night.

Speaker 9:

One of the experiments involves testing the effects of bubonic plague on humans, and a plan is hatched to develop a bomb that would release the plague into an enemy’s population. The idea is that the plague-infected fleas will infect rats and spread the bubonic plague. The prime target, California. The question is, “How to deliver a plague bomb over an ocean?” One solution, balloon bomb. There’s another method at the Japanese disposal. The bombs can be carried by aircraft launched from submarine aircraft carriers.

Speaker 10:

Japan is the only country in the world to have submarine aircraft carriers during the Second World War, and this really was a very serious threat. These planes could be fitted with these special ceramic bombs and used to bomb Los Angeles, San Francisco, San Diego.

Speaker 9:

The war ends before any plague bomb is used, but would the plot really have gone ahead?

Speaker 10:

If the operation had been put into practice, it would’ve worked, and I think the devastation caused in American cities would’ve been truly terrifying. Thousands of people would’ve been infected with the plague. Operation Cherry Blossoms at Night is probably one of the least known, but most amazing and potentially horrendous operations undertaken by any of the belligerent powers in the Second World War.

Trent Horn:

Now the attack was canceled after Japan surrendered in August, but cities like San Diego were, and still are, prominent bases of military operations, using a weapon that indiscriminately targets civilians with a painful, agonizing death, being covered in boils and vomiting blood as would happen with plague, that’d be a war crime. That’s the kind of death that the atomic bomb inflicted upon people at Hiroshima and Nagasaki who died of burn injuries and radiation poisoning in the days and weeks after the attacks.

Now, this brings me to the first of three arguments that are used to justify the bombings. The first is that Hiroshima and Nagasaki were fair game because they had extensive military installations, and so the civilian deaths were a tragic, unintended effect of attacking a legitimate military target.

Father Wilson Miscamble:

Truman sought to bomb Hiroshima and Nagasaki, two major military industrial targets, to avoid an invasion of Japan which Truman knew would mean, in his words, “an Okinawa from one end of Japan to the other.”

Trent Horn:

The killing of civilians in these cases was an intended effect of the bombs. This can’t be justified under double effect. If the cities had been evacuated for some reason, a different target would’ve been chosen. Declassified documents show that planners were advised “to neglect the location of industrial areas as pinpoint target since such areas are small, spread on fringes of cities and quite dispersed, and to place first gadget, bomb, in center of selected city for complete destruction.”

Now, you could justify using an atomic bomb on a naval fleet, for example, where civilian casualties are minimal, but at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, 90% of the casualties were civilians, which makes sense because the bomb was dropped on the center of the city. One document from the Truman Archive says, “All major factories in Hiroshima were on the periphery of the city and escaped serious damage. At Nagasaki, plants and dockyards at the southern end of the city were left intact. Another memo recommended that the bomb be used on a dual target that is a military installation or war plant surrounded by or adjacent to homes or other buildings most susceptible to damage and that it be used without prior warning.”

While some leaflets warning of bombings had been dropped previously on Japanese cities by US aircraft during the war, it’s unclear if the residents of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were warned. Some leaflets did use the atomic bombings as a means to coerce the Japanese to surrender. Here’s what one of them said. “America asks that you take immediate heed of what we say on this leaflet. We are in possession of the most destructive explosive ever devised by man. A single one of our newly developed atomic bombs is actually the equivalent and explosive power to what 2,000 of our giant B29s can carry on a single mission. This awful fact is one for you to ponder, and we solemnly assure you it is grimly accurate. We have just begun to use this weapon against your homeland. If you still have any doubt, make inquiry as to what happened to Hiroshima when just one atomic bomb fell on that city. Before using this bomb to destroy every resource of the military by which they’re prolonging this useless war, we ask that you now petition the emperor to end the war.”

We see here the bombs were used to incite terror and move the Japanese people to pressure their leaders to end the war. That’s terrorism, and it’s wrong. The second argument is that the atomic bombs were not weapons that indiscriminately targeted civilians. People say that the destruction they caused was on par with other conventional bombs that had been used in previous Japanese air raids.

Now, the Catholic philosopher, Ed Feser says the following in his reply to George Weigel’s use of this argument. He writes, “Weigel also notes that ‘the constraints on the bombing of cities set by the just-war tradition of moral reasoning had been breached long before the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.’ So what? This proves only that those earlier bombings were wrong, too, not that the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were not wrong.”

Another argument is that the civilian population was fair game because Japan planned to mobilize all of them to fight the allies. American General Curtis LeMay defended widespread carpet bombing by saying this. “The entire population got into the act and worked to make those airplanes or munitions of war, men, women, children. We knew we were going to kill a lot of women and kids when we burned the town. It had to be done.”

Father Wilson Miscamble:

The Japanese government had mobilized a large part of the population into a national militia which would be deployed to defend the home islands.

Trent Horn:

As Feser notes, Japanese civilians had not yet been mobilized to be soldiers at this time even if there were a plan to do that in the future. They were just civilians going about their daily lives amidst a conflict they had no responsibility in causing, so it was unjust to directly target them.

Imagine also if the Japanese or the Nazis had used this argument to justify bombing or sending biological weapons against American civilians. They might say the entire US population was mobilized to fight the war, so US civilians were fair game. A child collecting scrap metal or a mother tending her Victory Garden were no different than a soldier about to leave for Okinawa or Normandy. If we consider that reasoning to be a speciesist defense of a war crime, then we have to make the same conclusion about the atomic bombs that were used in Japan.

Finally, there’s the argument that the bombs were necessary to prevent greater loss of life that would’ve come from an invasion of the Japanese mainland. Now, I’ve already shown that this argument fails because it relies on the false moral theory of consequentialism. If you justify the atomic bombing simply because you want to save the most number of lives, then you open yourself up to justifying a whole host of other evils as well in the name of things like utilitarianism.

Another reason to be skeptical of this argument is that there’s good reason to think the bombings were not necessary to end the war. After all, the Japanese refused to surrender even after attacks on other cities, attacks that were more destructive than the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings. Why would we think that the bombs would cause them to surrender in this case when they had weathered far worse attacks?

Father Wilson Miscamble:

It was only the dropping of the atom bombs that allowed the emperor and the so-called peace faction in the Japanese government to negotiate an end to the war.

Trent Horn:

It’s also fallacy to assume that Japan’s surrender was due primarily to the atomic bombings that took place a few days earlier. Declassified documents show that the Japanese were more demoralized by the Soviet Union’s declaration of war and their surprise invasion of Manchuria, an area of China that Japan controlled. That was the element that made them consider surrendering.

Now, one of Japan’s sticking points in a surrender would’ve been their desire to keep their emperor as the head of state. In his autobiography, the US Secretary of War, Henry Stimson, said, “It is possible a clearer and earlier exposition of American willingness to retain the emperor would’ve produced an earlier ending to the war.”

Admiral William Leahy, the chief of staff to President Truman, an unofficial second-in-command during the time of the bombing, later wrote the following in his autobiography. “It is my opinion that the use of this barbarous weapon at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was of no material assistance in our war against Japan. The Japanese were already defeated and ready to surrender because of the effect of sea blockade and the successful bombing with conventional weapons.”

One thing motivating the bombings may have been a desire to pay back what happened at Pearl Harbor in 1941. President Harry Truman seemed to insinuate this kind of attitude when he announced the bombings in a broadcasted speech.

Harry Truman:

A short time ago, an American airplane dropped one bomb on Hiroshima and destroyed its usefulness to the enemy. That bomb has more power than 20,000 tons of TNT. The Japanese began the war from the air at Pearl Harbor. They have been repaid many fold, and the end is not yet.

Trent Horn:

One magazine poll taken two months after the war ended show that one in five Americans wished that more atomic bombs had been dropped on Japan before they surrendered. This shows that millions of Americans viewed the bombs primarily as a retributive punishment for the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and only secondarily as a deterrent to stop the war. We shouldn’t retributively punish civilians for something that happened in a war.

This debate isn’t about something that just happened 80 years ago. It’s about the broader principle of respecting human life even in the hell that is war. We have to be careful about allowing war to destroy what is good in us and turning a desire for justice into a lust for vengeance or letting war destroy us entirely. The argument that the atomic bombs were necessary to save more lives overall, that argument becomes difficult to make because, now, what if atomic bombs could destroy humanity entirely? Think about all of the nuclear scares that we faced since the dawn of the Cold War.

Here’s an interview with one of the bomb’s most famous creators, J. Robert Oppenheimer, who was portrayed recently in the film Oppenheimer, describing how he and others justified their work on the atomic bombs. As you watch the interview, note the tears welling up in his eyes as he talks about the justifications and the implications of this dreaded device.

J. Robert Oppenheimer:

… and that on the whole, we were inclined to think that, if it was needed to put an end to the war and, at a chance of so doing, we thought that was the right thing to do. We knew the world would not be the same. A few people laughed, a few people cried. Most people were silent. I remembered the line from the Hindu scripture, the Bhagavad Gita. Vishnu is trying to persuade the prince that he should do his duty and, to impress him, takes on his multi-armed form and says, “Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds.” I suppose we all thought that one way or another.

Trent Horn:

Recently, Pope Francis has questioned whether any war can be called a just war. While the principles of nations defending themselves from legitimate threats is always a valid expression of just-war theory, I agree with Eric Sammons from Crisis Magazine that, often, when we try to apply just-war theory to modern conflicts, the justification falls flat. He writes the following. “Although one could still try to argue that our original attack on Afghanistan was justified in light of 9/11, the expansion of the conflict and its ongoing nature clearly violated just-war theory. This is the one US conflict in my lifetime that best fits the just-war theory. The second Iraq war was a disastrous foray of foreign interventionism and score settling. The various US bombings in the Middle East over the years such as in Syria clearly violate just-war principles.”

As I said before, war is hell. It’s not glamorous. It’s not cool. We should honor those who fought for our freedom in wars precisely because of the horrors they endured, and we should never choose to intentionally inflict those horrors on innocent men, women and children who never signed up to face them in the first place.

Well, I hope that today’s episode was helpful for you, and I hope that you have a very blessed day, and I hope that you will pray for peace in our world. Thank you all so much and, yeah, have a blessed day.

If you like today’s episode, become a premium subscriber at our Patreon page and get access to member-only content. For more information, visit trenthornpodcast.com.