It's a late-summer afternoon in London, where Kylie Minogue, one of the grande dames of pop, is philosophizing about disco music. It’s transformative, she explains, because if you’re in the right frame of mind, the music can carry you away on its signature bass lines and horn sections. “When you’re at a club and you’re surrounded by people, you can still just shut your eyes and feel like you’re the only person on the dance floor,” she tells me. “Or you can be the only person in a room and feel like you’re out, surrounded by all this energy.”

I am talking to Minogue because in this tumultuous year, disco is experiencing a renaissance. Minogue is among several artists with new albums in 2020 that sound as if they’re echoes of the 1970s. Newly minted superstar Dua Lipa and pop chameleon Lady Gaga each put out chart-topping records this spring that served as bombastic revivals. Doja Cat cracked the Top 40 with her single “Say So,” an undeniable Chic callback. Jessie Ware’s latest is a steamy retro embrace, and even R&B’s King of the Underworld, the Weeknd, toyed with Technicolor production on his 2020 set, After Hours. But Minogue’s

latest, which debuts November 6, is the most on the nose. Its title: DISCO.

“In for a penny, in for a pound,” she says of the title. “Let’s just say what it is.”

It makes sense that the genre is seeing a revival in this god-awful year. Disco—born on Valentine’s Day 1970 in New York City—was pure fantasy, a strobe-lit, sex-fueled response to the late-’60s uproar and civil unrest. The four-on-the-floor beats invited revelers into a new decade, one in which the dance floors never cleared and the parties never stopped. Incorporating salsa, pop, funk, and soul, it promised not just inclusion but liberation under the mirror ball. As long as you were down to hustle, pump, and duck, it was all groovy, baby. Now, at the dawn of another new decade, with enough crises and death to make the ’60s feel almost quaint, the prospect of beaming into an alternate existence—imagined or MDMA-induced—is irresistible. “It’s three minutes of escapism and euphoria,” Minogue says of disco. “People need that.”

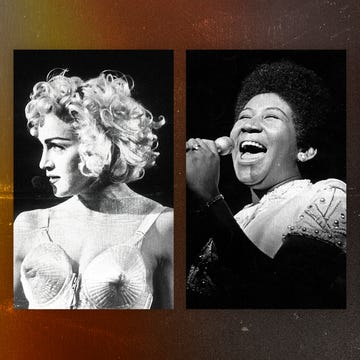

Minogue was two years old at the time of disco’s inception, but the Aussie was the foremost architect of its second coming. She scored her first hit in 1987 with a cover of “The Loco-Motion,”which topped the charts all over the world. Her self-titled debut LP arrived a year later and was effectively the birth of what people eventually called nu-disco. The resurgence burbled through-out the mainstream in the late 1990s and early aughts with releases from Jamiroquai (“Canned Heat”), Madonna (Confessions on a Dance Floor), and Daft Punk (“One More Time”). Even U2 wanted to flirt: “Lemon,” from the band’s 1993 record, Zooropa, is bathed in ’70s nostalgia. Minogue followed her debut with five albums in eight years, collaborated with fellow Aussie Nick Cave, and starred in films opposite Jean-Claude Van Damme, Pauly Shore, and Stephen Baldwin.

DISCO is as much an ode to the 6:00 a.m. set as it is a musical mission statement for the star, one of the biggest-selling female artists in history, with just as many honorifics as awards. The album is a return to everything she’s ever done well in song: gooey melodies, sheeny production, spellbinding reverie. In meetings with her creative team and cowriters, which began in person last fall before moving online as London went into coronavirus lockdown, Minogue says she kept everyone on track by routinely pulling up videos of Earth, Wind & Fire. She knew they were onto something when her longtime collaborator Biff Stannard called her in tears after finishing the sparkling lead single, “Say Something.” It was the first week of mandated quarantine, and London was eerily silent. “We were barely breathing,” she says of the pervasive feeling—but the track cut through.Hearing his reaction “made me cry,” she says. “Not just out of sadness, but that hope within the sadness. It’s that sweet spot of tears on the dance floor.”

Minogue’s twinkling plea for unity and togetherness did the same for me. The song became my soundtrack to a summer spent at home, blaring in the kitchen, the backyard, or the liv-ing room fashioned into a workout studio. It lined the make-believe concerts of my mind, drumming up anticipation for the crowds that will (hopefully) gather in 2021 and, more than once, despair from missing the throngs of people of years past. It prompts the existential question the entire genre faces as it resurfaces: What is dance music without a dance floor? Disco was born in the club, and when it returned in the early 2000s, it did so as the large-scale festival exploded in America. (DaftPunk’s 2006 Coachella set is widely considered the best show the event has ever seen.) But, at least for the time being, any revelry is currently confined to quarantine bubbles and at-home stereos. The clubs are closed, the event calendars cleared. It’s an oddity Minogue acknowledges. “It’s a kitchen disco,” she says. “It’s your lounging disco. A virtual disco.”

Reality may be damned, in other words, but the daydream lives on.