Alfa’s original 33 Stradale had a rough ride from race car to design star

History and legacy are powerful marketing tools for automakers. A familiar name or look creates a connection to something people remember, hopefully with fondness, and legitimizes new products as part of a lineage. That link is particularly explicit when it comes to Alfa Romeo’s recent 33 Stradale revival, a direct homage to the elegant ’60s supercar. It’s a lovely revival (you can read our design breakdown here) but when historical figures and events are drummed up in service of telling a story, the need for a clean, simple narrative can come at the expense of important context and nuance. The full story of the 33 Stradale deserves telling.

To be clear, Alfa Romeo takes its heritage seriously. The press release accompanying the new 33 Stradale accurately cites all relevant dates and figures. However, things are rarely clear-cut and straightforward when us Italians are involved.

Born from racing

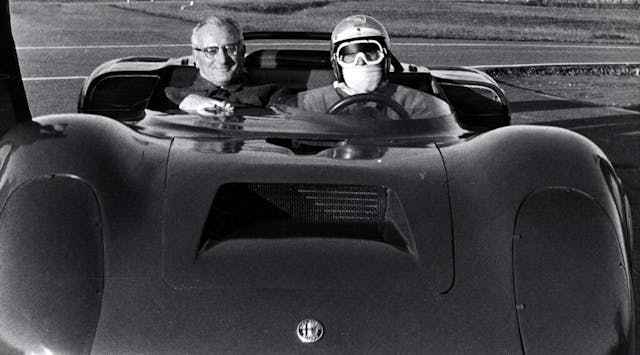

The origins of the “33” project date back to 1964. It was the first competitive race season for the Giulia TZ, and the little 1600-cc cars did well, though Alfa Romeo engineers knew they wouldn’t remain competitive for much longer. At the same time, Alfa Romeo was enjoying a period of relative financial stability, which encouraged its management to pursue a more ambitious racing program. Thus, inspired by the Porsche 904 GTS he saw winning the ’64 Targa Florio, Alfa designer Giuseppe Busso began working on a mid-engine 2.0-liter sports prototype.

Busso’s new racer shared next to nothing with production Alfa models. Nonetheless, it was assigned a “105” project code, as would a simple derivative of the Giulia sedan. Soon enough, Alfa’s engineers referred to the project “105.33.” The final two digits ultimately stuck.

The 33’s technical layout wasn’t revolutionary, but its unique chassis design was. The front suspension and steering box were attached to a large magnesium casting bolted to a middle section composed of three aluminum tubes about eight inches in diameter. These contained the rubber fuel tank and were arranged in an asymmetrical “H” pattern. Two cast magnesium braces connecting the aluminum tubes to the cross member holding the engine and rear suspensions completed the structure at the rear.

The first prototype ran in early January 1966, but Giuseppe Busso would not get much time to revel in the accomplishment. Days later, under orders from Alfa Romeo’s president Giuseppe Luraghi, the company’s experimental department begrudgingly handed over the “33” project to Autodelta.

Founded in 1963 by Carlo Chiti and Ludovico Chizzola, Autodelta began as the independent company responsible for assembling Giulia TZs on Alfa Romeo’s behalf. Between 1964 and 1966, Autodelta was gradually absorbed under Alfa’s direct control to become its in-house racing department.

Bumps in the road, Scaglione vs. Chiti

When Autodelta took over the 33’s development, the car was a long way from top of class. Its complex chassis required numerous modifications to withstand the stresses of competition, necessitating extra bracing that nearly negated its weight advantage over a more traditional structure. Still, Chiti had no choice. Ditching Busso’s brainchild right away would have strained his relations with Alfa Romeo’s engineers, already none too happy to have relinquished motorsport activities to Autodelta.

Work on the 33 road car (Stradale) began in late 1966, before the racing car’s development was completed. The chassis’ design remained largely the same as the competition version, except for the middle section that was built from steel instead of aluminum and made 100 mm (3.93 inches) longer to increase cabin space. Only slightly detuned for road use, the 1995-cc V-8 engine produced 230 hp at 8800 rpm, transmitted to the rear wheels via a six-speed manual transmission.

To design the 33 Stradale’s body, Carlo Chiti sought the services of Franco Scaglione, with whom he had worked previously on the short-lived ATS 2500 GT. A deal was struck in December 1966, and Scaglione’s drawings were on president Luraghi’s desk the following January.

Things soon got more complicated.

Years later, Scaglione would remember the construction of the 33 Stradale prototype at Autodelta as “the worst period of his life.” Accustomed to working with Turin’s finest craftsmen, Scaglione had a hard time dealing with Autodelta, a racing outfit ill-equipped to handle the creation of a road-going automobile from scratch. The situation led to intense clashes between Chiti (who was more invested in Autodelta’s motorsport activities than anything else) and Scaglione’s uncompromising drive for aesthetic perfection.

High complexity, low volume

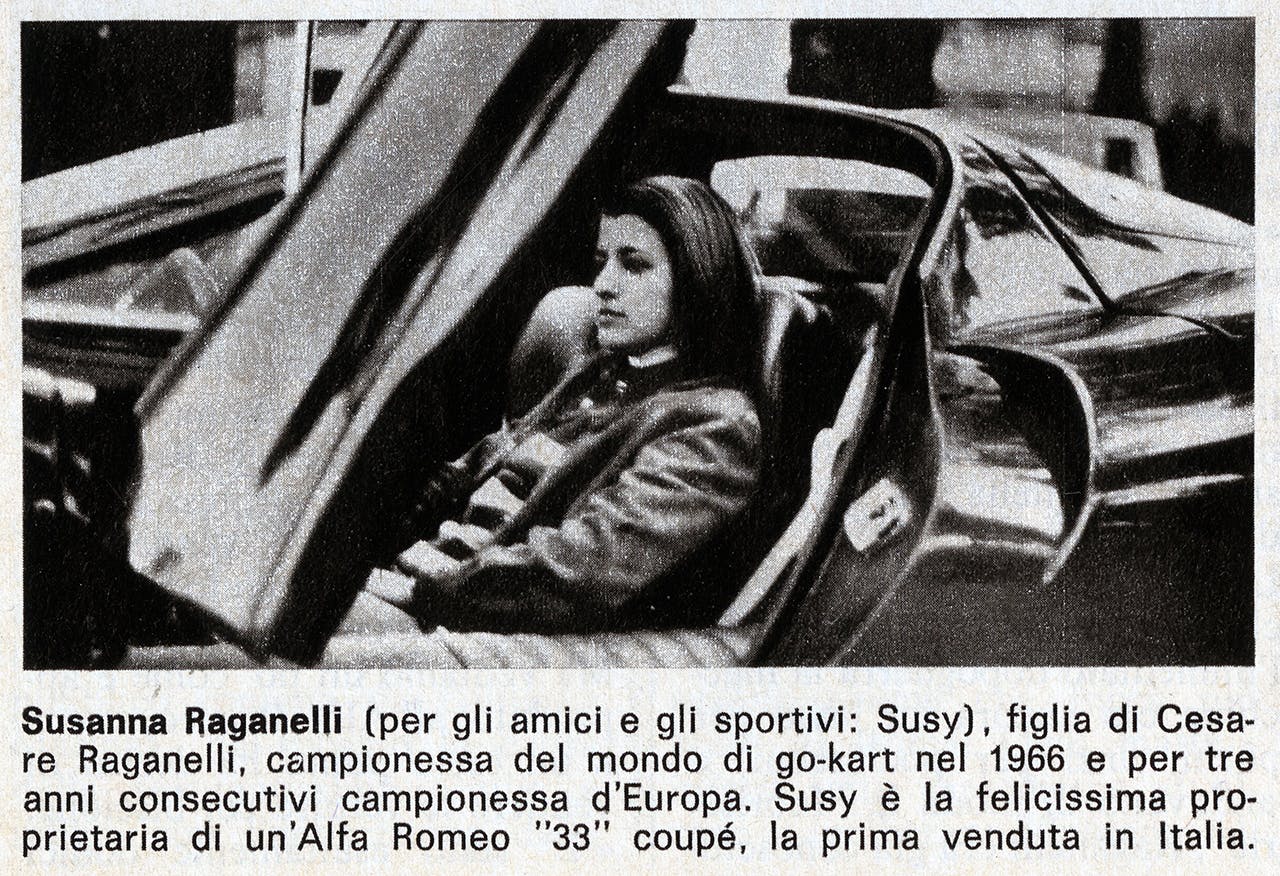

Still, despite numerous setbacks, the 33 Stradale prototype debuted at Monza on August 30, 1967. With a list price around 20 percent higher than the Lamborghini Miura, the 33 Stradale was a hard sell at $17,000. (That’s $156,600 in 2023.)

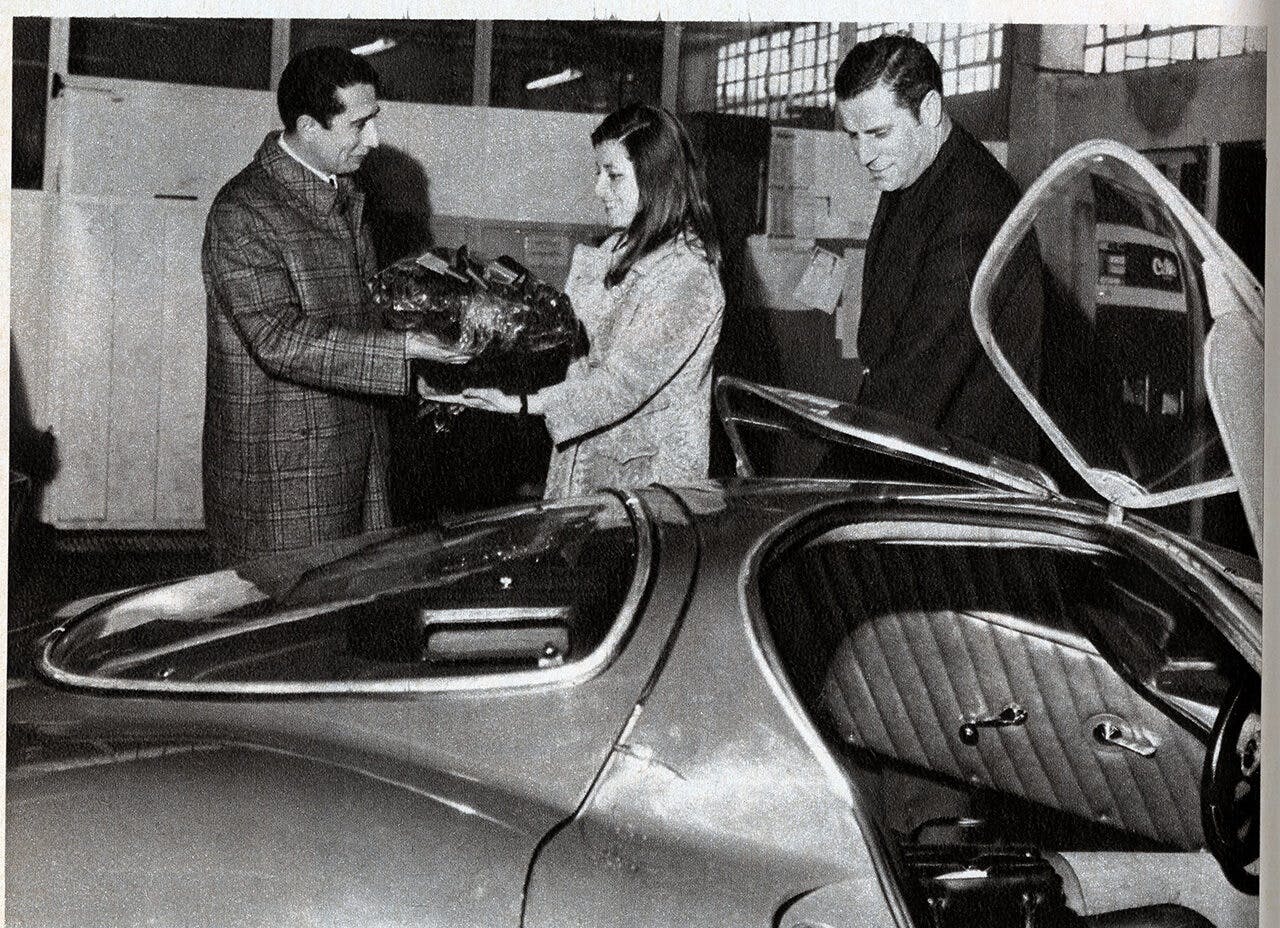

Making the cars proved even thornier. In October of 1967, against Scaglione’s advice, Autodelta entrusted manufacture of the 33 Stradale to the coachbuilder Marazzi. Seeing as the firm lacked the necessary know-how and expertise for a complex build such as this, production never took off and ended in 1969 after just 18 cars.

That total volume includes two pre-production prototypes, one of which belongs to Alfa Romeo’s heritage collection. These are instantly recognizable by their four headlights, which couldn’t be homologated. (The lower pair sat too close to the ground for a road car.) That run of 18 also includes five Stradale chassis that Alfa Romeo loaned to Italy’s most preeminent design houses of the era, so they could be turned into show cars. That leaves us with just 11 “production” vehicles, each slightly different from the others due to the nature of artisanal production process as well as individual customer preferences.

Still inspiring

Today, the 33 Stradale is the undisputed star of the Alfa Romeo museum collection. Yet, much as it happened with Van Gogh’s art, the fame and reverence the car currently enjoys came much later. Much more important to Alfa Romeo in 1967 was the go-ahead to begin construction of a brand-new factory in Southern Italy planned to produce 250,000 cars per year. A handful of supercars was, in comparison, a lark.

Over time, affection for the 33 Stradale swelled, a car that through years of savvy marketing has wed Alfa Romeo fans to its memory. It’s become a symbol, a bright red talisman whose spell can still seduce shrewd auto executives with plans for another Alfa Romeo “renaissance.” For this reason alone, the original 33 Stradale should be counted among the most important Alfas ever created.

***

Matteo Licata received his degree in Transportation Design from Turin’s IED (Istituto Europeo di Design) in 2006. He worked as an automobile designer for about a decade, including a stint in the then-Fiat Group’s Turin design studio, during which his proposal for the interior of the 2010–20 Alfa Romeo Giulietta was selected for production. He next joined Changan’s European design studio in Turin and then EDAG in Barcelona, Spain. Licata currently teaches automobile design history to the Transportation Design bachelor students of IAAD (Istituto di Arte Applicata e Design) in Turin.

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

My pulse quickens every time I see photos of a 33 Stradale!

Great, Informative piece- Love the Alfa background stories!

Beautiful car. Love the story behind it.