A Critique of the Garbage Can Model for Decision Making by Peace Bamidele

Concept Explanation

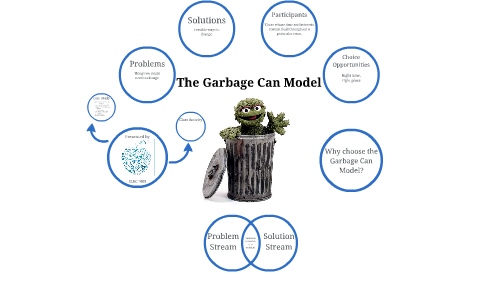

Kingdon introduces the garbage can model as an alternative to the rational model. Originally developed by Cohen, March, and Olsen (1972), the model presents the concept of “organized anarchies” where problems are not defined from the start and a logical approach to decision-making is lacking. With three characteristics including problematic preferences, unclear technologies, and fluid participation, the model sees decision-making as an environment where goals are not set beforehand, where participants are unclear about how to approach tasks, relying mostly on trial and error, and where participation of members in the organization is unequal. (Kingdon, 1984, 83-85)

Despite the seeming “chaotic” nature of the model, it has proven to be successful, hence, Kingdon revises the model to explain agenda-setting in governance. Mirroring the three characteristics of organized anarchies, Kingdon presents the multiple streams of problems, policies, and politics that interact to influence the agenda. Each of these “develops and operates independent of one another.” According to Kingdon, their greatest effect on agenda-setting occurs when they are “coupled” at critical times during what he termed “policy windows.” (1984, 86-88)

Critique

The garbage can model fails to answer the question of efficiency in decision making. It is not effective because there is no clear definition of what needs to be done and how; there are lots of moving parts with no direction. Because problems are not defined from the start, many important problems are swept under the rug.

Also, participants in the model wait endlessly for a “policy window” before key decisions can be made. Because of this, time is wasted, and interest in key issues wanes regardless of how important problems are. Even when policy windows do open, for example, with a “focusing event,” there is no guarantee that the two other streams will be ready: a solution (policy) may not be available and the “powers that be” (politics) may not be willing or equipped to act.

Finally, waiting for problems to find solutions and vice versa, a core feature of the model, suggests a lack of proactiveness; the model does not account for the need to investigate and prioritize problems that are important and urgent.

Strengths

A strength of this model is that it is more relatable than other models. In the world of decision making where knowledge is limited and all answers are not readily available, the model provides comfort to decision makers that they do not have to know it all before they get started. It is a more realistic approach to agenda-setting since many problems in governance are often “characterized by ambiguity, uncertainty, and political symbolism.” Hence, this model is well-suited in addressing multiple problems when information is limited.

I find this true in my experience. As former principal of 46 schools, I had to address multiple issues that emerged amongst students, staff, parents, and the community, while staying consistent with state and federal policies. A rational approach to addressing these issues would have been futile since I had limited resources (time and information) required to decide. The garbage can model came in handy for me in addressing the plethora of issues that I faced. Political leaders confront tougher challenges than I did, with voluminous and complex data that they are expected to sift through before deciding. In these situations, this model creates room for flexibility in problem solving by relying on solutions that can come from anywhere while eliminating the need to be overly comprehensive and rational.

Improvement

If Kingdon sought my advice on how to improve the model, I would suggest that he considers including defining problems beforehand. As stated earlier, when there is uncertainty about goals, key players may lose interest and important problems are left unattended to. Including problem definition in the model is a strategic way to make the model more efficient. This better harnesses people’s competencies and better coordinates activities in the direction of solving problems. Even when capacity is limited and all information is not immediately available, participants should still leverage available data to ensure that problems are defined, and plans are developed. These will galvanize the collective capacities of all stakeholders involved in solving problems.

References

1. Kingdon, J.A. 1984. Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies. New York: Longman Press.

2. University of Alaska System. (n.d.). The Garbage Can Model. Retrieved September 20, 2023, from https://faculty.cbpp.uaa.alaska.edu/afgjp/PADM606/Garbage%20Can%20Model%20Examples.pdf