Bruce Nauman at HangarBicocca

The Mice Race. Resistance and Social Media Society. A Finissage Review

Curated by Roberta Tenconi and Vincente Todolì with Andrea Lissoni, Nicholas Serota, Leontine Coelewij, Martijn van Nieuwenhuyzen and Katy Wan and titled Neon Corridors Rooms, the show at HangarBicocca displays a carefully selected number of pieces by the artist Bruce Nauman who, over the years, has worked extensively on the subjects aforementioned in the show’s title. Since the early days of the artist’s career in the late ’60s, much has been written about his work, in a consistent and still growing number of publications. Nauman’s work indeed still often offers opportunities for further analysis, and the study of his oeuvre still gives room to critics to rethink categories, subjects of art, and ultimately to shed light on the world around us.

This review is to be considered a continuation of the review The Imprisoned Cowboy, which I wrote on the occasion of Bruce Nauman show’s Contrapposto Studies at Punta della Dogana, curated by Carlos Basualdo and Caroline Bourgeois. In that text, I thematically juxtaposed the subject of the cowboy—a classic subject for American artists—and the figure of the slave—more connected to European tradition—as paradigms for freedom and imprisonment. I analyzed constructive and compositional choices and, together with direct and indirect referencing, suggested some thoughts about relevant topics in today’s artistic research.

Bruce Nauman, Dream Passage with Four Corridors, 1984 (detail), Exhibition view, Pirelli HangarBicocca, Milan, 2022,

© 2022 Bruce Nauman / SIAE. Courtesy the artist; Sperone Westwater, New York, and Pirelli HangarBicocca, Milan. Photo Agostino Osio

Once entered inside the main exhibition space of Pirelli HangarBicocca—a huge industrial space in the north periphery of Milano—the first piece my attention is drawn to is Dream Passage with Four Corridors, 1984. It’s a relatively big installation positioned just right in front of the entrance, slightly on the left side. It consists of a cross-shaped, white-painted, corridor structure, with a small room at the center. Each corridor is tiny, about 3 meters high, and 4 meters long, and only two of them lead to the room in the center. The whole structure glows from the many fluorescent yellow and red lights installed at the top. Entering the corridor, and upon reaching the center, you realize the tiny small room at the end center of the structure is not accessible. That’s because it’s fully occupied by 2 square wooden tables and 2 chairs. One table/chair pair sits on the floor and the other one is installed upside down, coming from the ceiling. The lightning is intense once inside the structure, and together with the mirrored composition of the furniture elements, it evokes feelings of displacement and disorientation. Walking inside the first corridor/room, I’m not the only one perplexed—a lady peeps inside the mirrored room from the corridor on the left, puzzled and confused.

Bruce Nauman, Dream Passage with Four Corridors, 1984 (detail). Installation view at Pirelli HangarBicocca Milan, 2022.

© 2022 Bruce Nauman / SIAE. Courtesy the artist; Sperone Westwater, New York, and Pirelli HangarBicocca, Milan

Photo Agostino Osio

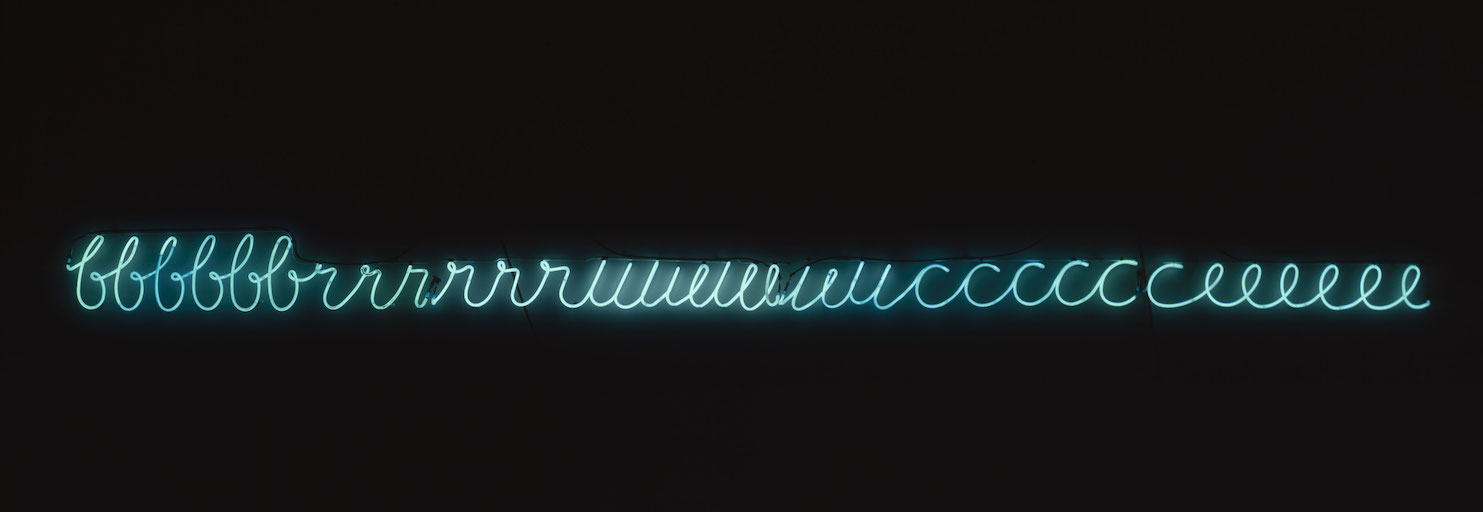

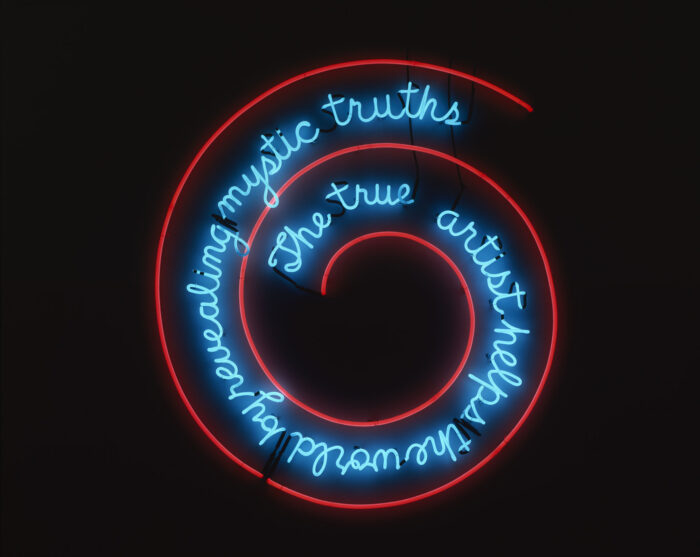

Once I walk out the installation, I walk to the neon light installed on the entrance wall. The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truths (window or wall sign), 1967. A neon tube light that spirals on the wall, from the center to the outside featuring the words from the title, hand-scripted in sort of elementary student calligraphy, and with a red underline. The structure of this image, even in its simplicity, carries a sense of vertigo and a weird sense of strength. This is probably one the most iconic works of the last century, and for this reason I cannot take its presence lightly. I ask myself, if it is here to contribute to the actual reading of the show, or if it’s just there as a valuable token.

Bruce Nauman, The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truths (Window or Wall Sign), 1967. Kunstmuseum Basel. © 2022 Bruce Nauman / SIAE. Courtesy Sperone Westwater, New York

Nearby, a wall structure about 4 meters tall faces another identical one about 40 centimeters away. At the top, green neons glow inside the white space. Even if the space is tiny, the piece is accessible. I don’t really feel like entering the narrow space it offers. Before me, a lady tries, but immediately escapes. I overcome my initial discomfort and pass through it. After me, another visitor tries as well. I observe him. He goes inside, and stops in the middle. He smiles toward the entrance. His partner is outside taking a picture. The couple seem to enjoy the moment of physical discomfort that Nauman offers them.

Many have done the same in the previous weeks. They have walked in and someone else has taken a picture, saved it on cloud, or posted it on the internet. With these dazzling and oppressive spaces, Nauman intended to stress the relation between the work and the viewer. But the photographic image is for obvious reasons oblivious of this intensity, and the social media propagation is even more distant.

I don’t think it is a mistake to report what the visitors do with the work and how they react. The pieces in the show are specifically conceived to stress these aspects, so it is definitely a matter of interest and needs to be reviewed. For the same reason, I think the show should be visited during opening hours and the opening should be avoided. It’s easy to imagine how hard it can be to maintain presence and awareness of your cognitive and bodily reactions during an opening reception.

My visit continues to Kassel Corridor: Elliptical Space, 1972. The idea of 2 facing walls is further explored this time into a narrow and curved space. I resist the idea of walking inside and I only gaze inside the structure. My eye follows the acceleration of the space and I feel the slight effect of vertigo, derived from the curved form and the consequent acceleration of the light’s chiaroscuro on the walls.

Bruce Nauman, Kassel Corridor: Elliptical Space, 1972

Installation view at Pirelli HangarBicocca Milan, 2022. © 2022 Bruce Nauman / SIAE

Courtesy the artist; Sperone Westwater, New York, and Pirelli HangarBicocca, Milan.

Photo Agostino Osio

After this piece, I walk to a little monitor, screening Walk with Contrapposto, 1968 and I enter the little space that hosts Get Out of My Mind, Get Out of This Room, 1968. It’s a small room, with low ceilings, and a light bulb that hangs from the roof. Two loudspeakers hidden behind the walls, play a recorded voice that repeats obsessively the sentence in the work’s title. With different tones and speed, all stressed and somehow exaggerated, it’s sometimes creepy and sometimes ridiculous. Visitors tend to come inside and leave quickly.

I think this work is really good: it has a very intense psychological quality, and at the same time it relates to the abstract tradition of the black square. The size of the room is also able to create a moment of strange intimacy within the cold and monolithic space of the HangarBicocca. In my opinion, the Hangar is a very difficult space to exhibit art. It has no natural light, and it has no articulation. It’s too high and too big for anything smaller than an airplane to be considered in relation to it, and it’s black. It’s almost a cosmic space, which does not provide enough visual coordinates for the works to organize into space. The only works that don’t feel totally lost here are video or light works. For this reason, I think the recent Steve McQueen show was nicely installed. Similarly to Nauman’s Corridors, Fontana’s spaces looked quite good, and I think most of the regular visitors of the Hangar remember Philippe Parreno’s show as one of their favorites.

After staying for a long time in the small space, I leave. I took some pictures of the show, just to remember the allocation of the pieces. I notice that these pieces are really hard to photograph. They’re somehow disproportionate and empty. From the outside, they mostly look like a temporary construction in a building site, made of drywall and wood. They don’t look interesting and it’s impossible to convey the body relation you develop with them and the sense of vertigo. It seems pretty useless to photograph them, but still visitors seem to enjoy taking selfies while trapped in Nauman’s green corridor.

Displacement and vertigo are definitely the main feelings that these works provoke in me, together with a sense of physical compression and inability to move freely. In Corridor Installation with Mirror, San José Installation (Double Wedge Corridor with Mirror), 1970, two convergent white corridors form a sort of triangular shape, when at the end a full-height mirror slightly turned on the right, reflecting only the other—identical—corridor. The structure is simple and the effect immediate. Somehow when entering into this narrow corridor you disappear.

Bruce Nauman, Corridor Installation with Mirror–San Jose Installation (Double Wedge Corridor with Mirror), 1970 (detail). Installation view at Pirelli HangarBicocca Milan. © 2022 Bruce Nauman / SIAE. Courtesy the artist; Sperone Westwater, New York, and Pirelli HangarBicocca, Milan. Photo Agostino Osio

These experiences are literal as much as they’re unavoidable. However, exhibiting a certain number of experiential, walk-thru pieces, can easily lead to some sort of “theme park” effect. Also we need to consider that vertigo is the main cognitive component of many forms of naive entertainment, like: the carousel, the rollercoaster, and the house of mirrors. Nauman intentionally explored this aspect with his work. But this problem also has to be framed in the context of the current art exhibition. Art institutions, as organizations, have to deal with many concerns, and they’re asked to relate to complex topics like power, class, race, society, and also—in my opinion—should respond to their means of production.

We live in a decade where western society is still reluctant to admit to the side effects of its agency. Art also has desirable effects and undesirable side effects when exhibited. In this show, vertigo is one of the first immediate effects the viewer can experience. But fruition today is not only just physical, and social media propagation generates a first wave of side effects—sometimes desirable, and maybe sometimes not so. Many artists today are clearly thinking in terms of social media virality. More visibility means often more visitors for the museum. And it is again the paradigm of the theme park that comes into play. A space for the collection of desires and the intensification of mass presence and economic transactions. Occasionally transforming an exhibition space into a theme park can be a good choice for an artist. But what if this transformation becomes permanent and museums turn into carousels? Can mystic truths still be revealed in this scenario? I believe Bruce Nauman’s work paradoxically works with the alphabet of the theme park (mirrors, corridors, vertigo) and on the contrary resists this process. The deliberate absence of compositional beauty, the poverty of the materials, its pure cognitive quality, and the stress it exerts on the body, make these works resistant to social media propagation, as their features cannot be fully expressed with images and indeed social media can’t really be a recipient for them.

On the side, in similar shape and manufacture—still made of wood and painted white—there is Funnel Piece (Francois Lambert Installation), 1971. This corridor structure is scaled up but not too big. Just enough so you lose perception of what’s surrounding you. You can move inside the corridor, and the light and the shape convey a sense of compression and again, vertigo.

Many of these works belong to the Panza Collection, interestingly. The collector did foresee the potential of minimal and conceptual art to meet the future needs of museums and exhibition spaces, which needed to be able to build, destroy, and rebuild many shows every year. The enthusiasm of the 1970s neo-avant-gardes for installation has been shared lately for artists in the early 2000s, and is always present when artists want to engage the viewer.

Bruce Nauman, Kassel Corridor: Elliptical Space, 1972 (detail) Installation view at Pirelli HangarBicocca Milan, 2022. © 2022 Bruce Nauman / SIAE. Courtesy the artist; Sperone Westwater, New York, and Pirelli HangarBicocca, Milan. Photo Agostino Osio

Still, after decades of installations, questions of pertinence need to be asked. We cannot be oblivious of the post-show anymore. What happens when the work is dismantled? Are we producing trash? What’s the impact of the show? Or in other words, is it necessary? Could the artist and the museum conjure the same visual, emotional, and aesthetic effect with lesser ecological impact? Mostly we still don’t think about it, but we need to start asking.

The economy and the simplicity of Nauman’s works is, in my opinion, very acceptable. We’re far from the grandiose, too frequent nonsense installations we see at the Venice Biennale. In his works, there is a sense of resistance to the excesses of the mass society and indeed the intention to develop a more intimate and one-to-one relation with the viewer is clear. The economy of means is evident, and there is mostly a sense of necessity of presence for the pieces that have been shipped around the globe.

In Wall with Two Fans, 1970, the structure is even simpler. Air blows from ventilators on opposite sides of two short walls. On one side we feel the breeze, on the other we don’t. Displacement is also at the center of the following installation: Going Around the Corner PIece with Live and Taped Monitors, 1970. It is a multi corridor installation, with 2 dead ends, 2 monitors on the floor, and 2 live cameras.

I remember the first time I saw this piece, years ago. I got really confused trying to understand which camera was showing what. I felt the presence of the surveillance camera, and the frustration of not seeing myself in the video. The circuit in fact is delayed and one of the two videos is a pre-registred tape. Nauman’s simplicity is always apparent and his works often cause a sense of puzzlement mixed with frustration. From that day, many years have passed and the feeling of frustration has left me, making room for a sense of alienation. I’m so used to seeing my image on screens, intentionally, unintentionally, in real time, delayed, that this piece no longer triggers much of a reaction.

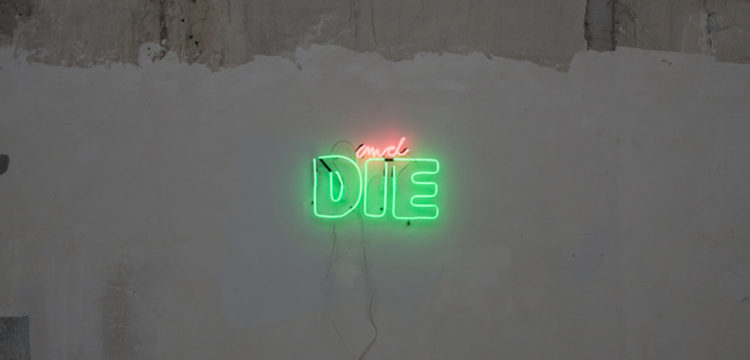

It’s interesting to continue to the neon wall titled One Hundred Live and Die, 1984. In my opinion, it’s one of Bruce Nauman’s best light pieces. It features an incredible number of neon lights organized in four columns along with small sentences of a verb associated with the word “live” or the word “die.” The installation is a remarkably complicated construction of overlapping colored neons mounted on a huge plinth. It’s almost like a small Times Square: fast, colorful, overwhelming and commanding. It comments on how much communication can take over the body and control it, even if today we might not feel this as an issue, as we have totally integrated this function into our lives, and now we ask our smartphones to tell us when we have to Sleep and Live, or Shit and Die.

I then walk inside Left or Standing, Standing or Left Standing, (1971/1999). A monitor with a brief poem introduces us into a triangular corridor that leads to a trapezoidal space filled with yellow light. It’s hard to describe the subtle feeling that the light gives when combined with the crooked perspective of the triangular corridors. The space inside is just empty, and I exit on a corridor that mirrors the entrance. Enigmatically, a corridor built in the same triangular shape and an identical monitor wrap around the installation. Nauman again takes us inside a some sort of spatial loop, using the basic vocabulary of mirroring to produce vertigo through repetition.

Bruce Nauman, Left or Standing, Standing or Left Standing, 1971/1999, © 2022 Bruce Nauman / SIAE.

Courtesy Sperone Westwater, New York

I continue toward Double Cage Steel Piece, 1974. Two big concentric metal grid volumes are open for the visitor to enter. I see smiling visitors entering the piece. The visual effect of these corridors is peculiar when, from the outside, you observe people on the inside. First, it’s hard to determine in which of the concentric cages the person is. Secondly, it gives you a strange sense of power, to observe someone submitting voluntarily to the containment structure. I recall the experience of being arrested, when I was in my 20s. The feeling was not good, so I prefer to stay outside and observe.

The intelligent combination with the neon entitled Hanged Man, 1985, makes me think that imprisonment can have many different effects. HangarBicocca’s visitors experience a consensual and temporary imprisonment—like it was for many of us during the pandemic years. But for many, imprisonment means real violence and tragedy. In the end life is a common ground that stands beyond the limitations of culture and social structures, and makes us similar in perception, in our body, and in our relation to death.

For the latter part of the show I consider worth mentioning in this compendium the piece Three Dead-End Adjacent Tunnels, Not Connected, which somehow explores the same idea of Double Cage Steel Piece. The work is made of casted metal, large about three meters and lifted from the floor just about thirty centimeters. Somehow it reminds me of the Pentagon. The structure is rigid and not functional. It doesn’t display the efficiency of the panopticon but more an allegorical quality of the architecture, frequent in buildings where power is held and exerted.

The scale of the piece makes it very clear. We just have been treated like rats in this labyrinth of corridors that the artist has orchestrated for us. The same is valid for Model for Tunnels: Half Square, Half Triangle, and Half Circle with Double False Perspective, 1981, a sculpture made with plaster, iron and wood and to be considered as a model for a complex network of corridors.

Finally, for this section of the show, I’d like to mention Untitled (Model for Trench, Shaft, and Tunnel), 1978. This sculpture is different in quality, color and material from the previous ones. It still resembles a model for an architecture, but this suspended structure is less a prison and more a path of ascension. It has more of an abstract and allegorical quality, and the three circular shapes represent something like a path toward liberation. The glass fiber also has more to do with the light, than the heavy physicality of plaster and metal of the previous two. I believe this allegorical approach is fundamental to Bruce Nauman’s work, and even if it can appear sometimes minimalist at first sight, it relates instead to the late medieval period and early Renaissance. As for classical artists, the use of geometry is mostly made to convey hidden meanings, and are open to a more speculative reading.

Bruce Nauman, Neons Corridors Rooms, exhibition view at Pirelli HangarBicocca, Milan, 2022. © 2022 Bruce Nauman / SIAE

Courtesy the artist; Sperone Westwater, New York, and Pirelli HangarBicocca, Milan. Photo Agostino Osio

Concerning this show, I think these are the pieces that contributed more to elaborate relations between theme park entertainment and the experience of vertigo as a producer of cognitive displacement. Also, in my opinion, these are the pieces of the show that challenge more the current standards of fruition of mass scale exhibitions.

The show is not over though, and actually continues in the HangarBicocca’s area named Cubo, where we can find Mapping the Studio II with color shift, flip, flop, & flip flop (Fat Chance John Cage). I personally think this video has been discussed ad infinitum and, in the context of this presentation, only makes the show a bit redundant.

Finally, once out in the outdoor space, you have to pass through the beautiful installation of Raw Materials, 2004. An impressive collection of twenty one recordings and audio works spanning all artist’s career, densely installed one after the other. The walk through is confusing, surprising, and definitely stimulates the senses, as the audios are repetitive, absurd, and loud. Again, Nauman discourages the desire to reorganize your experience logically and leaves you with a sense of puzzlement mixed with amusement, nicely wrapping up the show, with a last ride in the HangarBicocca’s ferris wheel.