German artist Neo Rauch on ‘punching back’ at critics as he holds second solo exhibition in Hong Kong

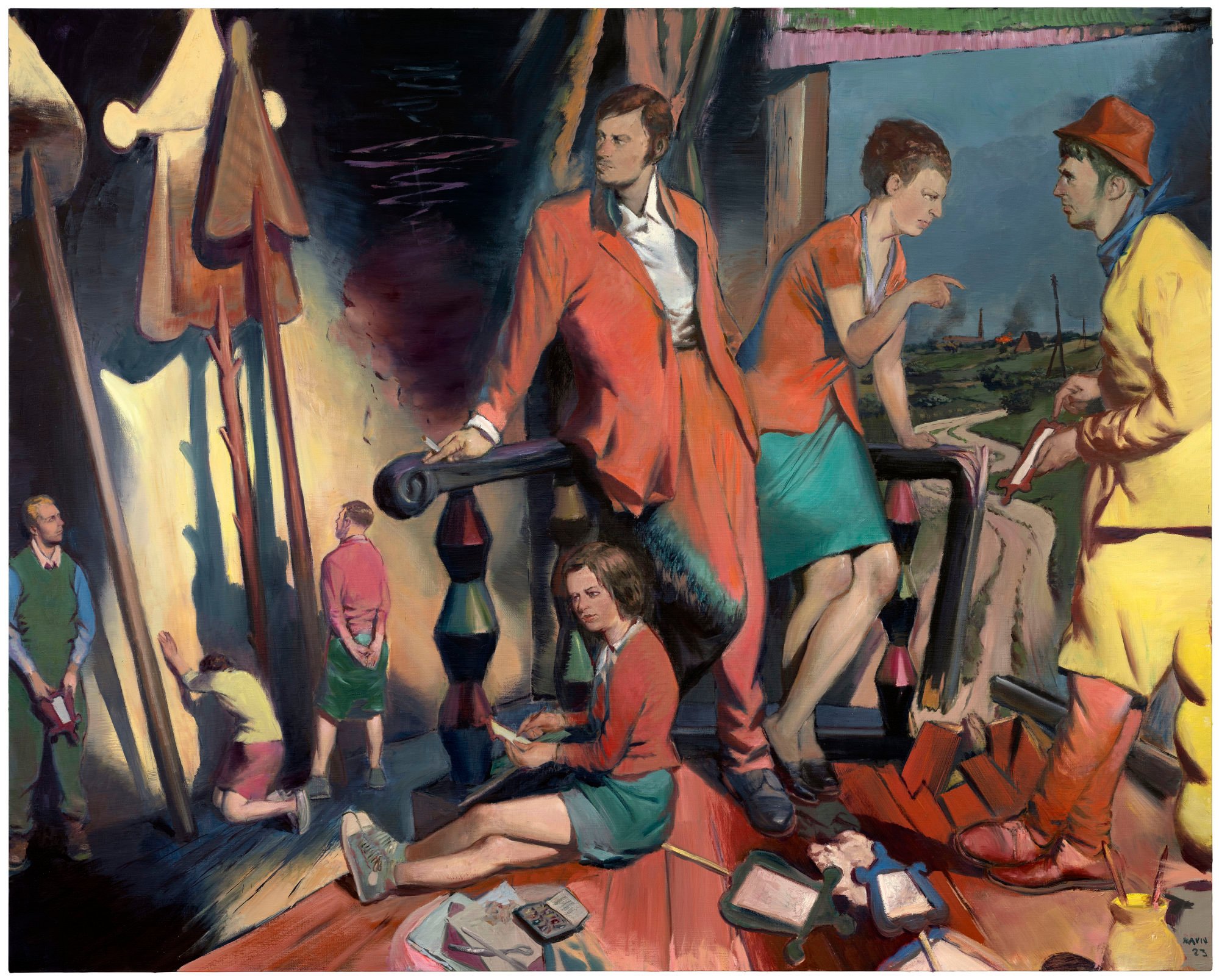

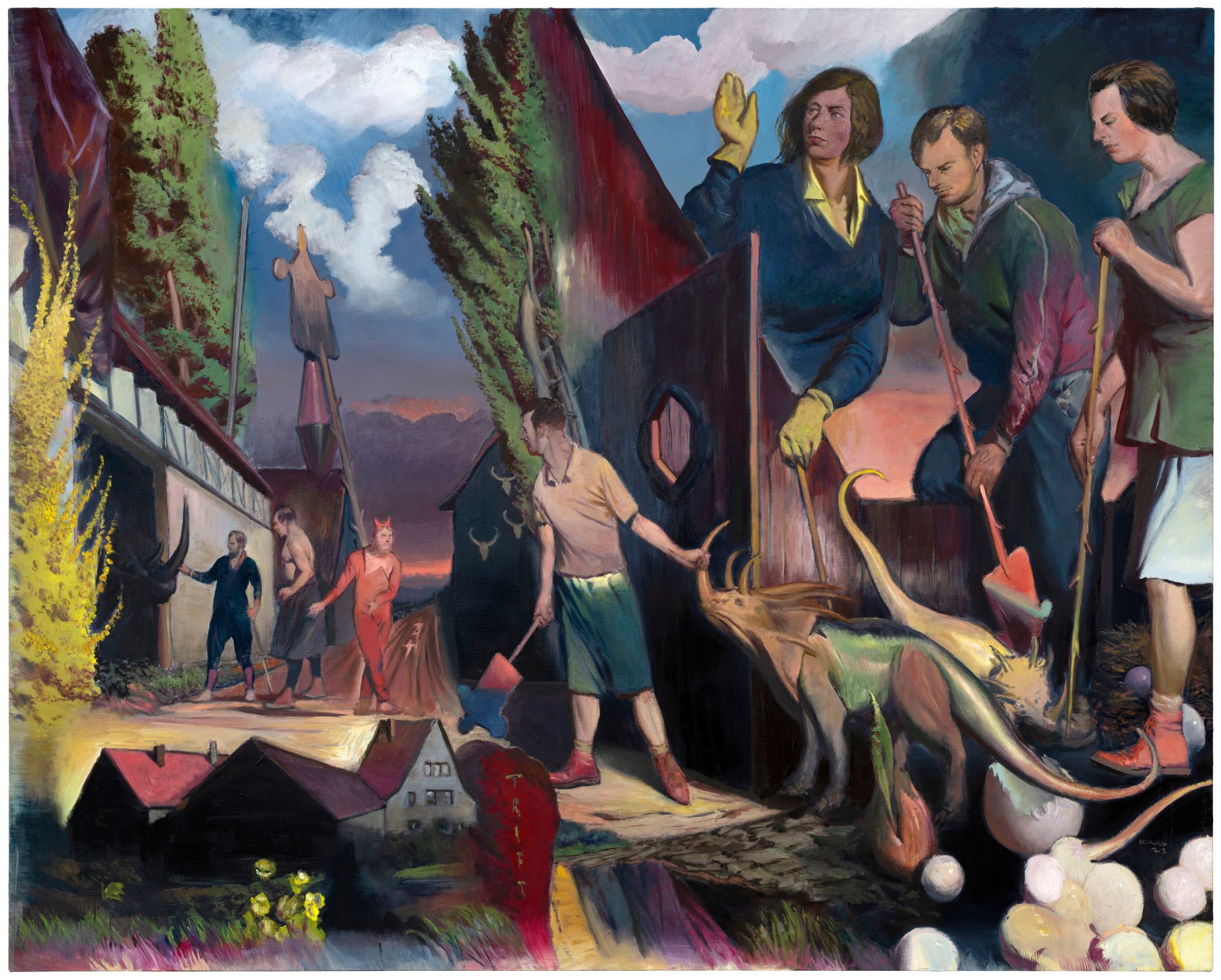

- Neo Rauch is back in Hong Kong with his unique brand of figurative painting, showing his troubling landscapes across 15 paintings at David Zwirner

- He talks about his spat with art historian Wolfgang Ullrich, previous run-ins with critics and journalists, and gaining control of his paintings’ characters

In March 2019, the German artist Neo Rauch opened his first solo show in Asia at David Zwirner’s Hong Kong gallery. In English, it was called “Propaganda”; the Chinese title was translated as “publicity”.

From a distance, Rauch’s work always looks quaint. Then you move closer and observe the mutilations, the claws, the grotesque instruments, the approaching storms. The viewer is chilled and intrigued by a sense of impending disaster.

Four years later – during which the world has seen many very real disasters – Rauch once more has a show at David Zwirner in Hong Kong.

In German, it’s called “Feldzeichen”. In English, the translation is “Field Signs”, which suggests something agricultural – “the farmer and his potatoes,” as he puts it one morning in the gallery – although the original reference is to the ancient banners carried by Roman troops to mark their conquered territories.

Rauch enjoys double meanings but he doesn’t spell them out. Every one of the 15 paintings in the show has an untranslated German title.

In some of the new works, the old Roman standards are held aloft and abandoned in corners; they loom large and they shrink. His is a world of huge insects, tiny individuals, multi-horned beasts and glinting blades, as if his compatriots, the brothers Grimm and Heinrich Hoffmann (writer of Der Struwwelpeter), had joined forces to create a dark, social-realist fairy tale.

He says these troubling landscapes spring from his subconscious, which seems likely because 28 days after he was born in 1960 in Leipzig, in what was then East Germany, his parents were killed in a train crash. If your childhood begins with such a shadow, your psyche probably recognises ultimate terror can happen within a heartbeat.

Hong Kong show spotlights comic strip Old Master Q’s supporting characters

Making art is a compulsion. In a 2016 documentary about him, Comrades and Companions, he describes how the characters in his work “accost me or mock me – they simply don’t let me sleep”.

In addition to such mental torture, when he’s working he has to wear gloves, so thick they might belong to a deep-sea diver, to protect him from his allergy to turpentine.

A few weeks after that interview, the ever-hovering storm broke. Out of the blue, he became involved in a major spat with German art historian Wolfgang Ullrich.

On May 21, 2019, the newspaper Die Zeit published an essay by Ullrich that accused Rauch of shifting to the right politically, especially in his refusal to depict contemporary society or to declare himself a fan of political correctness. (Rauch sees himself as someone who tends the dying flame of figurative painting, which he’d learned in East Germany while the Western art world leapt upon other forms of artistic expression.)

The following month, Rauch sent Die Zeit a photo of a work he’d finished of a man – generally thought to be Ullrich – defecating onto a paintbrush that he intended to apply to a canvas on which there was a Hitler-like figure. This surreal response attracted considerably more attention than the original article.

Rauch had seemed a pleasantly intense, somewhat introverted individual in that 2019 interview so one might assume it was the subconscious – or the turpentine – at work and regret had kicked in later. But no.

“At first, I wanted to write a letter, but Rosa said, ‘No, paint a picture,’” he says, referring to his wife, the painter Rosa Loy, a commanding woman who dismissed the Post’s photographer at the previous interview before a single photo was taken. The gallery had warned he wouldn’t talk about the episode but he perks up at the mention.

“It’s always the same if you punch back,” he continues. “You feel better. I wouldn’t show my enemies the other cheek. I’ve done this twice before, reacting to journalists’ insults. The first time, someone described my painting as childish, harmless stuff, so I painted one called Harmless.”

Harmlos (2002), which depicted a rampaging giant, was sold by David Zwirner at Frieze the same year. As the asking price had been US$1 million, in that instance revenge was sweet.

“And the second one was… what was the second one?” While he’s trying to process that memory, he adds about the one he sent to Die Zeit, “It’s a great painting, I’m very proud about this painting. For example, the ear of this ridiculous guy is so well done.” Does he mean the art critic’s ear? “This person is not an art critic,” he says. “He’s an activist with a political agenda.”

Ullrich went on to write a book, Becoming an Enemy, about the East-West conflict in art; the painting Rauch sent Die Zeit was sold at a charity auction for €750,000 (US$820,000). Rauch, despite feeling better, put up a notice in his studio saying “Never answer a critic”. But what about the effect on his subsequent work?

The very exhibition title suggests a man staking a claim to his own land. It has a curious work called Die Beladung (“The Loading”) that depicts a gigantic figure in thick gloves placing rucksacks on men’s backs. Is he burdening them? Provisioning them, like troops, for some unknown purpose? With Rauch, it’s difficult to know, but that looming gloved figure has authority.

Has he now gained control of his characters? “It might be,” he says, with a smile. “I’m too close to see this clearly.”

In Der goldene Weg (“The Golden Way”), with its bright border like a medieval painting, a young girl lifts a standard and walks into the distance, bringing the viewer along with her, into Rauch’s uncontemporary world.

18 captivating artworks on 4 islands reveal another side of Hong Kong life

“Always with the beginning of a new painting, you have to pretend to be innocent,” Rauch says. He likes to explain that his process occurs in an “almost trance-like state”, but looking at Trift (“Pasture”), in which another gloved figure dominates – with a paintbrush? a stick? – the brutish creatures below, you begin to wonder if it’s quite unwitting.

“What was the name of that second painting,” he murmurs once more to himself.

“Neo Rauch: Field Signs”, David Zwirner, 5-6/F, H Queen’s, 80 Queen’s Road Central, Central, Tue-Sat, 11am-7pm. Until February 24, 2024.