Seattle’s Gum Wall: An Oral History

Ew.I’ve just descended into the vaguely medieval confluence of shadows and gray cobblestone in Post Alley when a voice nearby articulates why I’ve avoided this stretch of Pike Place Market for so long. Gum is everywhere—a polychromatic pox dots the ground and canvases brick facades. Slimy stalactites hang from pipes. Like any Seattle resident, I know what I’m stepping into. But apparently the tourist to my right isn’t prepared for this much tackiness. Upon discovering it, she expels some Alexis Rose–like disgust, then kicks a heel back to see if her shoe has acquired an intractable passenger.

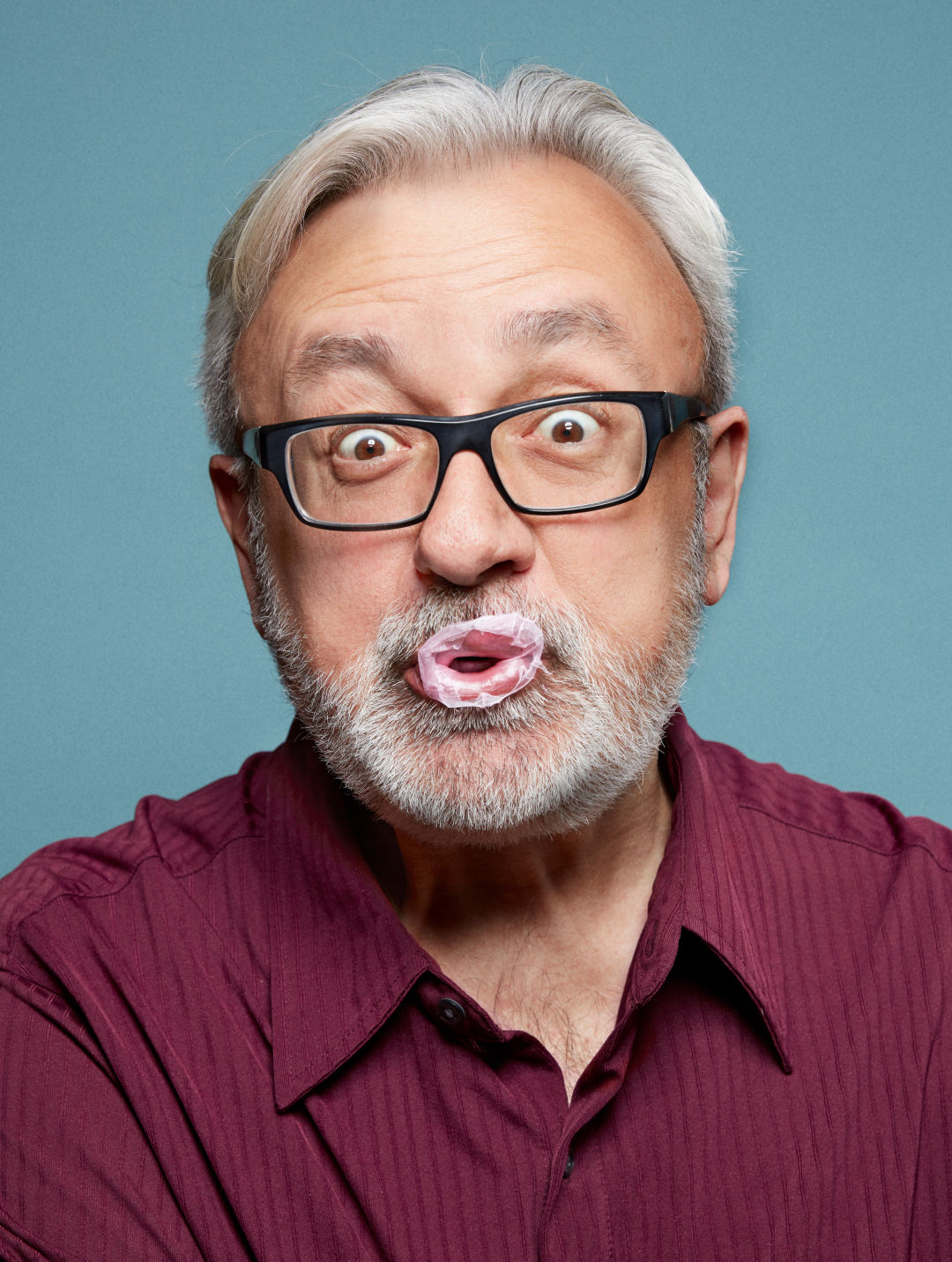

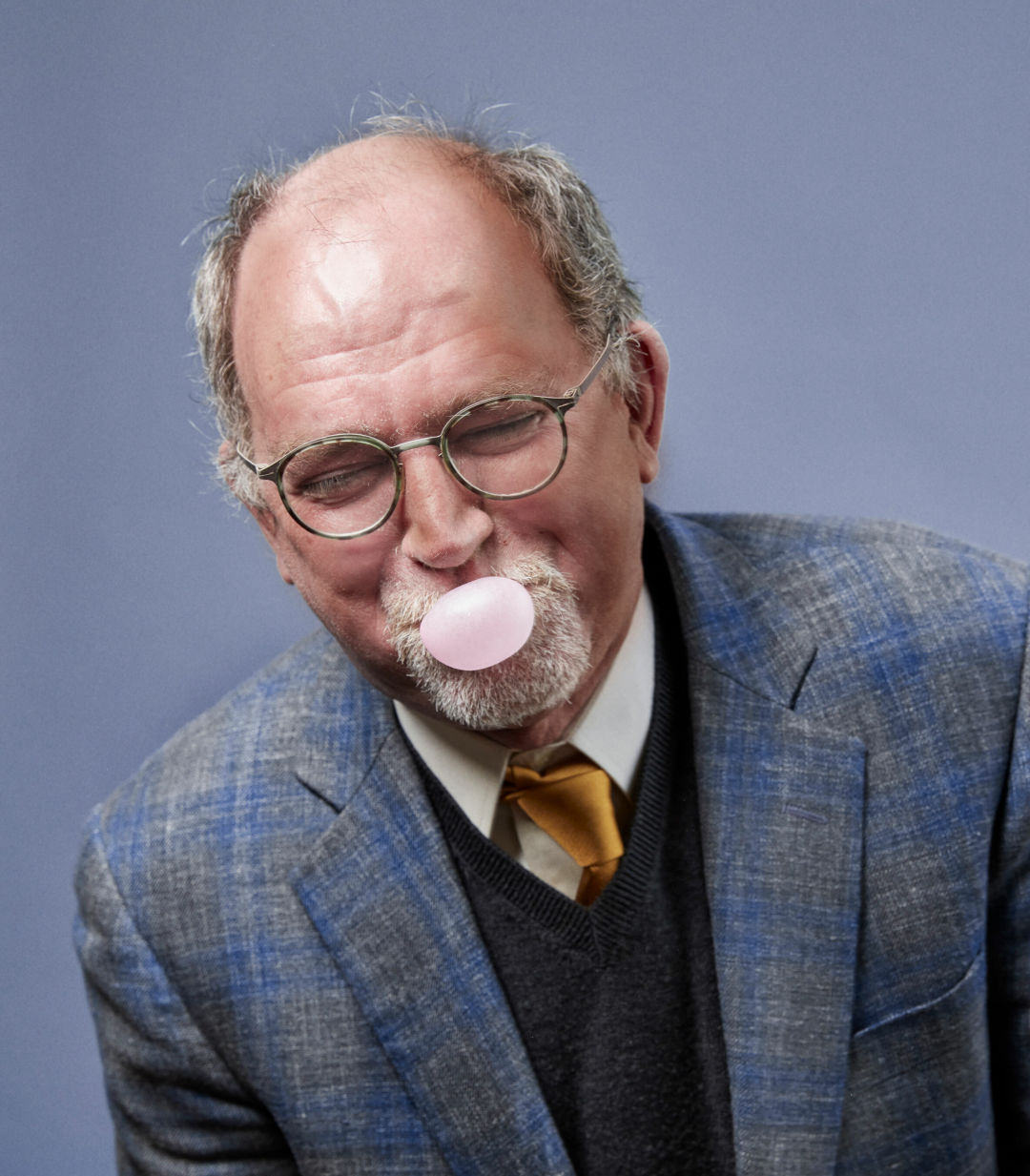

Most visitors don’t fixate on their footwear in this particular passageway. The alley’s rainbow-colored walls serve as coveted photo backdrops. Clout chasers love to pose in front of them with tilted heads, puffed cheeks, and ballooning bubbles. Or with gum pulled like strings of mozzarella. Or with fully extended tongues that appear to be, but aren’t actually, licking the lumps off the wall. There’s a reason the Seattle Selfie Museum set up shop next to the influencer magnet, and veritable city landmark, known today as the Gum Wall.

Grunge famously took off here in the early 1990s, but a different flavor of griminess quietly surfaced in Seattle around the same time. While Nirvana’s Nevermind had been years in the making before its release, the Gum Wall’s emergence was as spontaneous as the improv sketches in the adjacent Market Theater. Chewed-up wads spread across that stretch of Post Alley; visitors tucked graduation cards and wedding photos and Jesus portraiture behind the sticky globs. Some embraced it as living art. Others just thought it was gross. Pike Place Market management ordered multiple takedowns shortly after its genesis.

Many locals try to steer clear of it. But, in the three decades since its arrival, the Gum Wall has nevertheless persisted as a beloved, weird, and somewhat mysterious representation of our city. Those side-eyeing the Dubble Bubble affixed to every conceivable surface in the alley may not know the long, strange history spawned from a tiny alcove of Unexpected Productions. Time only adds to its mythology.

Let this be the one story that sticks.

The Cast

Mary Bacarella

Former volunteer with Unexpected Productions who later joined the Pike Place Market Preservation and Development Authority (PDA). She’s now its executive director.

Photographs courtesy the subjects.

Rooted in Spontaneity

In May of 1991, an itinerant improv group, Unexpected Productions, settled into a permanent home at the Market Theater. Its competitive comic showdowns, Theatresports, had developed a rabid following during stints at the Group and Intiman theaters, often drawing more than 400 spectators.

Randy Dixon: We were looking for a home. The Market at the time was looking for stuff other than restaurants to draw people in at night. Around ’91, we moved into the Market Theater.

Mary Bacarella: No more garbage can in the back of my car full of props.

Randy Dixon: Surprisingly quickly, the audience followed us. We actually thought it was going to take a while. I can’t remember the exact reason why we kept them outside, but prior to the show, we would line people up the alley.

Mary Bacarella: That’s how the Gum Wall started.

Randy Dixon: There are lots of myths and rumors and lies about how it started. … The actual original Gum Wall was the brick wall between our door of the theater and what is now the entrance to the elevator lobby. I don’t know what it is, 10 feet, 12 feet.

Mary Bacarella: I would say within the first year or so we saw it happening, right away.

Randy Dixon: Originally, whoever started it, they would put pennies on the wall. They would take gum, put the gum on the wall, and then press a penny into the gum. So it was actually a penny wall. And it just kind of took off.

Blowing Up

As the gum spread up Post Alley, it initially drew the ire of Pike Place Market management.

Randy Dixon: We would get letters saying how disgusting it was.

Mary Bacarella: We have a letter from John [Turnbull] saying, “please clean up your wall of gum.”

John Turnbull: It used to be a line, waist high, and there was gum, gum, gum, thumbprint, penny, in each of ’em. And then someone came by and took all the pennies. But people started climbing up the gutter pipes and everything else [to attach gum to the wall].

Emily Crawford: There were these periodic cleanings because tenants in the alley were not happy with gum on their wall.

Randy Dixon: We were out there with our paint scrapers and whatnot.

John Turnbull: The bricks are really tough to scrape, as Randy knows.

Mary Bacarella: None of this hazmat suit, like in the later years. I don’t even know if we had gloves on. Did we clean it twice or three times?

Randy Dixon: It was at least twice I think.

John Turnbull: And then you just forgot it.

Mary Bacarella: My understanding was, at some point, someone from the Market came to us and said, “It’s as quirky as the rest of the Market. You can leave it up.”

The oddity manifested in photos tacked behind wads, gooey stick figures, and some more ambitious art.

John Turnbull: One day I was walking out the door of our office, and I looked up, and there were two people dressed sort of like—one was like a French mime with a black-and-white striped shirt and a little red beret, and there was a woman with a little rolled skirt on. And she had an artist’s palette, with different colors of gum on it.

They hung an empty gold frame on a brick wall at the back of the Bistro. He had a stick or something. And he’d say, hmm, “I need some green”.… And she’d pick up a piece of green, chew it, and give it to him. And then he—I hope he had gloves on—he’d pat it up on the [wall]. He made this whole little landscape drawing. It was just a little bit of performance art, no stage.

Randy Dixon: I would walk down that alley, and there’d be people getting their wedding pictures taken in front of the Gum Wall.

Mary Bacarella: If you walk through the Market, you hear people going, “Where’s the Gum Wall, I think it’s down here. I think the Gum Wall’s down here.”

Randy Dixon: Bret Boone, who was the second baseman for the Seattle Mariners for a number of years, he and his family were taking Christmas pictures for their Christmas card or whatever. Like, Bret Boone, you can get pictures taken anywhere, and you’re doing the Gum Wall? [Boone could not be reached to confirm this decision.] That’s when it started kind of snowballing…oh, this is bigger. People know more about it.

Mary Bacarella: Different stores will sell gum, so you can pick some up and chew it and put it on the wall.

Aika Takayanagi: We have Dubble Bubble, we have Hubba Bubba, we have Nerds.... The gumball machine’s the crazy one.

Randy Dixon: I did a show a number of years ago, and I put a speaker in the window, facing out into the alley, and then I invited people to come in to be interviewed and talk to me about why the Gum Wall was on their list of things to do in Seattle. And more times than not, they’re like, “Boy, it’s much bigger than I thought”—people from Australia, from Japan, from all over Europe.

Mary Bacarella: Even the people that might have thought it wasn’t—and we still get this in the Market—that think it might not be sanitary or something they might not enjoy, they do find it fascinating. You can’t not find the Gum Wall fascinating.

Randy Dixon: When we were displaced and moved to Intiman [in 2011]…there wasn’t a lot of traffic, which seemed to give people more permission. It seemed like it doubled in size in a few months just because nobody was around to sort of police it.

John Turnbull: And then it disappeared.

Intermission

“I don’t know if you know this, but Washington was the state with the first reported case of Covid-19, and between you and me, I blame the Market Theater Gum Wall.”

Improv or Imitation?

The narrower Bubble Gum Alley in San Luis Obispo, California, also has a murky past, but most agree disorderly locals started it in the middle of the twentieth century, long before the Gum Wall took shape in Seattle. It’s not any more well-kempt; the alley’s only been cleaned twice since the ’70s.

“In Seattle there is a wall of gum. It is gross. It is beautiful.”

Body Double, Please

Though the Gum Wall appears in the 2009 romantic drama Love Happens, star Jennifer Aniston reportedly missed the Seattle shoot for “scheduling” reasons. Riiiiiight.

“It’s like removing the Blarney Stone.”

From top: Featureflash Photo Agency, melissamn, Lev Radin, s_buckley / shutterstock.com

A Heated Cleanup

After more than 20 years of DIY cleanings, Pike Place Market management hired a contractor to deploy a more industrial method in 2015. Over 130 hours, workers used pressure washing to extract a literal ton (2,350 pounds) of gum from Post Alley—enough to fill 94 five-gallon buckets.

Emily Crawford: It was hands down one of the craziest experiences of my life. We knew that we would get media attention for it, especially because [a full cleaning] had never been done. But nobody saw the tidal wave of interest that came through. No one saw that coming.

John Turnbull: It went viral.

Mary Bacarella: It was on the front page of The New York Times.

John Turnbull: We had a new hire who had just started with marketing. And that was his very first job, to just write this half-page press release, “We’re going to be removing the gum off the Gum Wall.” So his first day on the job, he got like 20 million impressions.

Kelly Foster: I way underbid, because I made assumptions on what it would take to remove the gum, and my assumptions were not good. Part of the problem was, there were areas of the wall that were as, oh, gosh, as thick as I would say, at least 10 inches, if not a whole foot thick.

Image: Alberto Cruz / Flickr CC

Emily Crawford: There was gum on both sides—the ceiling, the floor. It had become more of a tunnel than a wall.

Kelly Foster: So we had some equipment that worked really good for [sidewalk] gum removal. It’s a steam machine, and it’s primarily designed to clean and degrease institutional or industrial kitchens. We do work with Swedish [Health Services]. And once a year, we detail-clean their kitchens, where we get behind the grills and the hoods and all this kind of stuff and use a steam machine that just melts the grease off. It’s very, very hot. But it didn’t work as well when you had 10 inches thick of gum.

Emily Crawford: It had gotten out of hand. It was at a point where the PDA couldn’t just continue to let the tunnel grow.

Kelly Foster: You would hit it with this steam machine, and it would kind of drill a hole in it, and then just slowly reform back to the shape that it was in before you hit it. So it required my team to dig at it literally with rakes and pull it off the wall with the steam machine. As you’re pressure washing, you could smell the Juicy Fruit, or you’d get a deal of Spearmint gum or something—you would have some strong smells. One of the guys, he’s vowed to never eat gum ever again in his life.

Emily Crawford: My assignment was to make this palatable because we knew people were either going to be like, “Thank God,” or be really pissed.

Kelly Foster: We had to barricade the area off while the staff was working. Once they were done, as soon as we took those barricades off, they rushed the wall like it was Black Friday at Walmart. And everybody just started putting gum up.

As workers cleared different sections of the alley, locals affixed wads to the walls. One group showed support for France after terrorist attacks in Paris.

Egan Orion: Back then, our flash mob community was constantly looking for a way to connect with what was going on in society. This was totally different than most of the things we'd done before. I’m sure that our peace sign with the Eiffel Tower in the middle of it was covered up pretty quick.

Image: Courtesy Egan Orion

Others weren’t so harmonious.

Kelly Foster: We had a couple instances where people got really mad. They were quite upset about the fact that we were cleaning it. One guy broke through the barricade line and kicked some of the equipment that was resting on the ground, and kicked over the steam machine. The PDA security staff told them, you gotta leave, and escorted them right away, but there was some concern there.

Emily Crawford: Seattle is not a straight and narrow, tidy city. People who were upset about it were like, “Why are you trying to take away the quirkiness that makes this place so cool?”

Kelly Foster: It was a lot of labor. I think it cost me about $10,000 to clean it. And I think we billed the customer like $10,500.

Emily Crawford: We knew it was going to come back.

A Legacy to Chew On

Cascadian Building Maintenance would perform similar cleanings in the following years but hasn’t returned since the start of the pandemic. While a virtual gum wall to support local workers popped up during the Covid shutdown, only the real one remains. Its legend continues to grow.

Randy Dixon: I’ll be in the alley, and you hear walking tours going by. And they always say this thing about like, “Oh, they didn’t allow gum in the theater. Anyone who was chewing gum had to spit out their gum, so in a protest, people started putting the gum on the wall.” Nothing about the pennies. I’m just kind of like, what? How do you police gum in the theater? That’s the most common [myth] I hear.

Mary Bacarella: Everybody’s got an opinion. Most people seem to go, it’s the Gum Wall. It’s in the Market. It’s ours. And then there are the ones that just don’t like it. It’s too messy. It’s unsanitary.

Emily Crawford: Having my office window off of the alley, where the Gum Wall was, my daily experience of the Gum Wall was a shrieking, smelly, loud, stinky, disgusting mess. I never got to open my window. God forbid. God forbid.

Egan Orion: The Gum Wall is a really bizarre piece of our local history. In a way, it’s sort of disgusting and iconic, all at the same time. And I think we just wanted to be a part of it.

Mary Bacarella: As long as I’m here, we’re having a Gum Wall.

Randy Dixon: It’s a great piece of living public art in Seattle. And it’s ever changing. Doing improvisational theater, which is a collaborative art form, the notion is that the Gum Wall is the ultimate artistic statement about that notion of collaboration, in that nobody can take credit and go, “I started the Gum Wall.” It’s a bunch of people.

All day long, if you stand there and watch people, every time somebody puts up a new piece of gum, it’s a new piece of art.