The Dark Matter of America's Foremost Musical Satirist

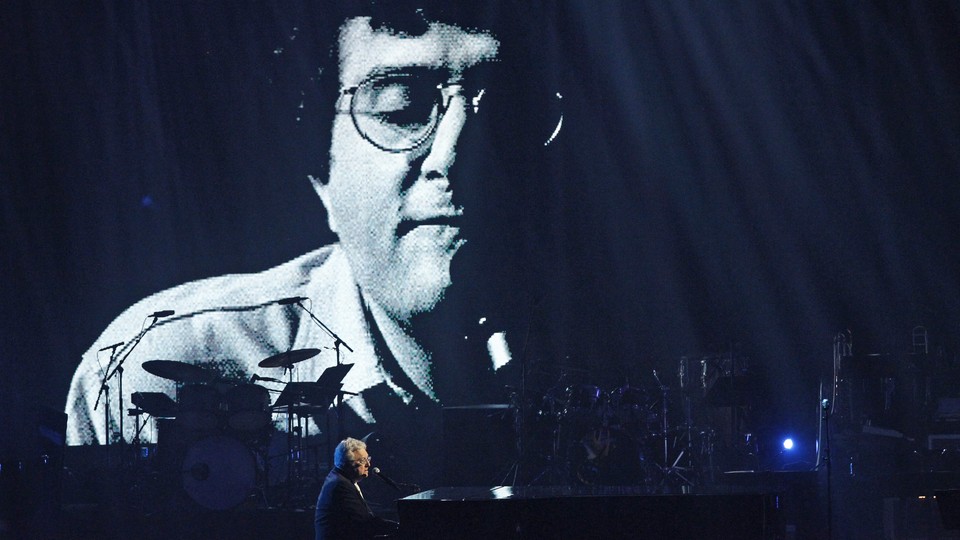

Randy Newman has done as much as any songwriter to anticipate the tragicomic place where the country finds itself. And his best work may still be ahead.

To the question, “Do you know the work of Randy Newman,” the answer is too often, “The guy who did the Toy Story soundtrack? ‘You’ve got a friend in me …’ that’s him, right?”

And okay, sure. He composed soundtracks to the whole Toy Story series, among other well-loved films: Ragtime, The Natural, Parenthood, Awakenings, The Paper, Maverick, A Bug’s Life, Meet the Parents, Seabiscuit, Monsters University, and more. But summing him up like that is a bit like saying, “F. Scott Fitzgerald. Wasn’t he a screenwriter?”

Because while Newman is a talented and sought-after soundtrack composer, he is also a solo artist with a catalog as original as any in popular music. It stretches back to 1968. Yet even most folks who can hum his biggest commercial hits, “Short People,” “Mama Told Me Not to Come” (popularized by Three Dog Night), and “I Love L.A.,” fail to grasp how he would be regarded in a more just and discerning world. For Randy Newman is the foremost musical satirist of his generation––and the characters he has created and themes he has explored over his career show as nuanced a grasp of America’s dark currents and humanity’s crooked timber as any songwriter has managed. In fact, there may be no one in the American songbook whose work did more to anticipate the tragicomic place the United States finds itself in today.

His latest solo album, Dark Matter, added to that corpus when it dropped earlier this month. To grasp its worthy continuities and its single disappointment, I must first take you back.

The eponymous debut album that Randy Newman released in 1968 was a portent of all that followed. Its 11 tracks might be described as rock or pop except that they were backed by a full orchestra. Poignant songs about romantic longing, like “Love Story (You and Me)” and “Living Without You,” were juxtaposed with character-driven vignettes like “So Long Dad,” darkly irreverent commentaries on the human condition like “I Think He’s Hiding” (Newman’s response to Nietzsche’s claim that “God is dead”), and “The Beehive State,” a quirky tune of ambiguous meaning set on the floor of Congress. In time all those modes would be refined, all those subjects explored.

The songwriter’s second album, 12 Songs, established his willingness to create the darkest of unreliable narrators to plumb subjects as fraught as men who prey on women, as in “Suzanne,” and America’s long history of racist minstrelsy and stereotyping. His approach carried risks as surely as Vladimir Nabokov’s decision to channel Humbert Humbert in Lolita and Norman Lear’s creation of Archie Bunker for All in the Family. Newman benefitted from coming up in an era when critics protectively explained nuanced art to mass audiences rather than trying to stoke umbrage. Here is Rolling Stone’s Bruce Grimes in a five-star review of the album:

Randy's concern with stereotyping led him to include "Underneath the Harlem Moon," the only song on the album he didn't write. Composed in the Twenties, every line contains some of the most blatant racial typing ever set down in song: "They just live for dancin'/They're never blue for long/It's no sin to laugh or grin/That's why darkies were born." Newman follows this cut with his own contemporary parallel, "Yellow Man."

After performing these songs at the Lion's Share, Randy said, "I was afraid I might be misunderstood and someone would jump on stage and beat hell out of me." Randy Newman's songs are not heavy-handed, and his humor is rarely direct.

He comes at you from corners.

This oblique approach bore fruit on his next album. Its title track, an anti-slavery song, might have been ignored as heavy-handed or predictable if the liberal songwriter had taken a straightforward approach. Instead, Newman captured the horrors of enslavement anew with “Sail Away.” The listener only gradually comes to see that the narrator waxing poetic about the wonders of America is actually duplicitously coaxing Africans aboard a slave ship, falsely promising that once they cross the ocean, they’ll just “sing about Jesus and drink wine all day––it’s great to be an American.”

And the B-side of the album was just as cutting. Its first song is still relevant to anyone pondering the Strangelovian strains of American jingoism. He titled it “Political Science”:

No one likes us, I don't know why

We may not be perfect, but heaven knows we try

But all around even our old friends put us down

Let's drop the big one and see what happensWe give them money, but are they grateful?

No, they're spiteful and they're hateful

They don't respect us, so let's surprise them

We'll drop the big one and pulverize themAsia's crowded, Europe's too old

Africa's far too hot and Canada's too cold

South America stole our name

Let's drop the big one there'll be no one left to blame usWe'll save Australia, don't want to hurt no kangaroo

We'll build an all American amusement park there

They've got surfing, tooBoom goes London, boom Paris

More room for you and more room for me

And every city the whole world round

Will just be another American townOh, how peaceful it'll be, we'll set everybody free

You'll have Japanese kimonos, baby

There'll be Italian shoes for me

They all hate us anyhow, so let's drop the big one now

After all that, it felt like a relief to arrive at a song about the Cuyahoga River fire of 1969, when an oil slick on the polluted Cleveland waterway caught fire, inspiring lyrics that deserve immortality: “Well the Lord can make you tumble / And the Lord can make you turn / The Lord can make you overflow / But the Lord can’t make you burn.”

(Not that he lets the Lord off either.)

Rolling Stone’s list of the 500 best albums of all time includes the songwriter’s next effort, Good Old Boys. “This album is no simple character study, but a composite survey of the roots and institutionalization of Southern bigotry in the 20th century,” Winston Cook-Wilson observed in Pitchfork––“in other words, the diciest and most formidable project Randy Newman had (and has) ever attempted.” It opens with “Rednecks,” where a “good old boy” narrator recalls watching a segregationist governor on a late-night program:

Last night I saw Lester Maddox on a TV show

With some smart ass New York Jew

And the Jew laughed at Lester Maddox

And the audience laughed at Lester Maddox too

Well he may be a fool but he's our fool

If they think they're better than him they're wrong

So I went to the park and I took some paper along

And that's where I made this song

What followed might’ve compared to “Southern Man,” Neil Young’s jeremiad against racism south of the Mason Dixon line, with Newman marshaling a character to skewer his own prejudice rather than scolding, “when will you pay him back?”

But unlike Young, Newman wasn’t content to let smug Northern liberals off the hook, even by omission. Thus a turn toward the end of the song when the redneck narrator pivots to an observation laden with that worst epithet: “Down here we're too ignorant to realize / That the North has set the nigger free / Yes he's free to be put in a cage in Harlem in New York City / And he's free to be put in a cage in the South-Side of Chicago /And the West-Side /And he's free to be put in a cage in Hough in Cleveland / And he's free to be put in a cage in East St. Louis / And he's free to be put in a cage in Fillmore in San Francisco / And he's free to be put in a cage in Roxbury in Boston.”

If every last listener was uncomfortable, Newman felt he’d done his job. The song may be the most uncompromising instance, among white songwriters, of putting artistic vision before commercial concerns: Here is the first track of an album that risked offending anti-racists who misunderstood its intentions; could hardly have done more to alienate the white South; and closed by taking added shots at a literal list of Northern cities where an upcoming artist with a small following would want to perform.

As if to confound listeners even more, Newman revisited his Southern man on later tracks, showing that he was neither a misanthrope nor a one-note polemicist, for “Birmingham,” “Marie,” and “Mr. President, Have Pity on the Working Man” were as humanizing in their portrayal of their subjects as “Rednecks” was scathing and unsparing. Never has cynicism been packaged with so much sentiment. Says Mike Powell, “Newman can get an orchestra to pull tears from you like a pickpocket. His sleight-of-hand is to bring out a monster and make you see the human underneath.”

Rounding out the concept album, Good Old Boys also included perhaps the most beautiful song that Newman ever wrote, “Louisiana 1927,” and two songs distilling the populist Louisiana governor Huey P. Long, “Every Man a King” and “Kingfish.”

Quoth the latter song, told from Long’s perspective:

I'm a cracker

And you are too

But don't I take good care of youWho built the highway to Baton Rouge?

Who put up the hospital and built you schools?

Who looks after shit-kickers like you?

The Kingfish doWho gave a party at the Roosevelt Hotel?

And invited the whole north half of the state down there for free

The people in the city

Had their eyes bugging out

Cause everyone of you

Looked just like me

(Before Twitter, populists actually delivered spoils to their supporters rather than expecting them to stay loyal based on no more than occasional demagogic missives.)

Now let’s skip ahead to 1979. The album is Born Again, the song, “It’s Money That I Love,” a straightforward if exaggerated portrayal of an ethos you’ll no doubt recognize:

I don't love the mountains / I don't love the sea

I don't love Jesus / He never done a thing for me

I ain't pretty like my sister / Or smart like my dad

Or good like my mamaIt's money that I love

It's money that I loveThey say that's money / Can't buy love in this world

But it'll get you a half-pound of cocaine / And a 19-year-old girl

And a great big long limousine / On a hot September night

Now that may not be love but it is all right

A few years later, he released Trouble in Paradise, an album best known for “I Love L.A.” The song would play at the Great Western Forum during Lakers games when I was a kid, in spite of those inevitable Newman twists that distinguished it from boosterism:

From the South Bay to the Valley

From the West Side to the East Side

Everybody's very happy

'Cause the sun is shining all the time

Looks like another perfect dayI love L.A. (we love it)

I love L.A. (we love it)

We love itLook at that mountain

Look at those trees

Look at that bum over there, man

He's down on his knees

Look at these women

There ain't nothing like 'em nowhere

While Trouble in Paradise touches on everything from apartheid to the changing demographics of Long Beach as experienced by a white old-timer who doesn’t much like his new neighbors, its best tracks, by my lights, capture the particular entitlement of wealthy Southern Californians so adeptly that I’m still marveling. The self-indicting portrait of the narrator in “Take Me Back” is deliciously subtle. And here’s a bit of “My Life Is Good,” an upbeat song that zeroes in on the essence of a character nearly anyone associated with a private school in a wealthy area has met:

The other afternoon my wife and I

Took a little ride into Beverly Hills

Went to the private school our oldest child attends

Many famous people send their children there

This teacher says to us "We have a problem here

This child just will not do a thing I tell him to.

And he's such a big old thing. He hurts the other children.

All the games they play, he plays so rough..."Hold it teacher / Wait a minute

Maybe my ears are clogged or somethin'

Maybe I'm not understanding the English language

Dear, you don't seem to realize:My life is good

My life is good, you old bag

So many Newman characters, for all their different milieus, share an abiding disregard for the effect that their actions and attitudes have on those around them. That theme is exaggerated for effect on a track from the 1988 album Land of Dreams:

I ran out on my children / And I ran out on my wife

Gonna run out on you too baby / I done it all my life

Everybody cried the night I left / Well almost everybody did

My little boy just hung his head / I put my arm put my arm around his little shoulder / And this is what I said:"Sonny I just want you to hurt like I do

I just want you to hurt like I do

I just want you to hurt like I do

Honest I do honest I do, honest I do"

The same character carried his disregard for his family over to his attitudes toward the public:

If I had one wish / One dream I knew would come true

I'd want to speak to all the people of the world

I'd get up there, I'd get up there on that platform

First I'd sing a song or two (you know I would)

Then I'll tell you what I'd doI'd talk to the people and I'd say

"It's a rough rough world, it's a tough tough world

And things don't always go the way we plan

But there's one thing we all have in common

And it's something everyone can understand

All over the world sing alongI just want you to hurt like I do ...

Honest I do, honest I do, honest I do”

Then, every so often, amid the awful characters and biting satire on Newman albums, the unreliable narrators are sent off on break, and Newman does deeply earnest with the best of them. In relief, the gut-punch quality of the songs are accentuated.

That last linked song is from Harps and Angels, a 2008 release that was, one senses, supposed to mark the conclusion of a low-point in American politics. “Just a few words in defense of our country,” a circumspect Newman began, “… whose time at the top could be coming to an end. Now, we don't want their love. And respect at this point's pretty much out of the question. But in times like these we sure could use a friend.”

The defense of the country turns out to be a widely ranging history of bygone powers far less defensible. The indictment includes a critique of War on Terror excesses.

Newman leaves us with this observation:

The end of an empire

Is messy at best

And this empire's ending

Like all the rest

Like the Spanish Armada

Adrift on the sea

We're adrift in the land of the brave

And the home of the free

When I listened to that song I started worrying, because it sounded a bit like a culmination. I thought there was a chance that Newman wouldn’t make another album. Almost a decade passed without one. And that brings us up to the present year.

My hope that there would be a new Randy Newman album was reinvigorated months ago when, without warning, a new single appeared online. Its title: “Putin.” So political events had drawn the master satirist back to the piano! The song is told from the perspectives of a chorus of sycophants and the Russian leader himself, as in this scene, inspired by Putin’s geopolitical incursions into Crimea and its coastline:

He and his ex-wife Lyudmila are riding along the shore of the beautiful new Russian Black Sea

Let's listen in, a great man is speaking:

“We fought a war for this?

I'm almost ashamed

The Mediterranean

Now there's a resort worth fighting for”

“Putin” made me want a new Randy Newman album like I want a new season of The Wire; like I want Brian Wilson and Paul McCartney to collaborate writing songs for an HBO alt-history series about Brian joining Paul, John, and George in a supergroup circa 1969; like I want lost chapters of Don Quixote to be discovered in Salamanca.

And I kept imagining what the song after “Putin” might be.

Here was a songwriter who had excelled at commenting on politics; on Southern white populism; on “America First” jingoism; on nuclear war; on characters who love nothing more than money; on entitled men who prey on women, betray wives, chase women, and narcissistically crave public attention. What would the greatest musical satirist of his generation, who approaches nearly every subject obliquely, say about Donald Trump, a figure more ripe than any other for his dark humor and tragicomedy?

The new album, Dark Matter, is a delight. Its title track is a meditation on the relationship between science and religion in Newman’s inimitable style. And as it turned out, the song after “Putin,” “Lost Without You,” is one of those earnest Newman gut-punches: A widow speaks to his deceased wife, recounting the last time she saw their adult children and the instructions she gave about what to do when she’s gone:

Hush up, children

Let me breathe

I've been listening to you all your life

Are they hungry, are they sick?

What is it they need?

Now it's your turn to listen to me

I was young when we met

And afraid of the world

Now it's he who's afraid

And I'm leaving

Make sure he sleeps in his bed at night

Don't let him sleep in that chair

If he holds out his hand to you, hold it tight

If that makes you uncomfortable

Or if it embarrasses you

I don't care.

A Trump song never did come––and I got over it. Maybe this moment is too new to capture. In fact, I began to think, maybe Randy Newman has already given us everything there is to say about Trump and Trumpism in bits and pieces over the years. But then I listened to his recent interview with Marc Maron. Of course the president came up. And the songwriter mentioned that he might have found a way to write about the man––that a song with an oblique approach was rattling around in his head.

And okay, sure, I know there are concerts to perform to promote his new album; more films to score; Grammys to win; and golden years to enjoy; but I can’t help thinking that Newman could conceivably still have his best album in him. So if a single titled “Ivanka” drops one day, I’ll drop everything to listen. And if that appears on a final concept album? I’d say, “The country turns its lonely eyes to who? Randy Newman.”