The Hard Lessons of Amanda Bynes’s Comeback

The former teen star broke down in excruciatingly public fashion five years ago. Her return brings up pointed questions about the way society handles struggling celebrities.

In 2008, writing for The Atlantic about the slow-motion car crash and paparazzi dissection of Britney Spears’s apparent mental breakdown, David Samuels assessed the significance of the moment when the pop star shaved her head in full view of photographers in a Los Angeles hair salon in 2007. After that point, Samuels wrote:

Britney Spears departed the planet of normal bubblegum celebrity story lines and entered the heavenly realm of pop myth. America’s sweetheart had dramatically and publicly un-edited herself, removing the customary trappings and protections of celebrity to reveal the damaged psyche of a fractured person who was no longer able or willing to regulate her public behavior.

Spears, in other words, was literally broken down in the public eye, enabled in her self-exposure by a fleet of photographers who’d turned stalking into a highly lucrative, highly predatory industry. Embedded in their morbid routine of waiting for her, sometimes for 12 hours at a time, was the seeming inevitability of the biggest payday of all—the chance, as Samuels wrote, that “one day Britney will roll her car into a ditch or be taken away again strapped to a gurney.”

Amanda Bynes is four years younger than Britney Spears, and her public breakdown came around five years later. Apart from that, the two performers have eerily similar stories: Spears got her big break at the age of 11, when she was cast in the 1990s revival of Disney’s The Mickey Mouse Club, while Bynes joined Nickelodeon’s All That in 1996, when she was 10. Both women came of age as public figures. Raised in the glare of camera flashes like poultry chicks under heat lamps, both women found, by the age of 26, that they could no longer endure the scrutiny.

The difference with Bynes’s breakdown was that it involved Twitter. Spears’s, as Samuels documented in his story, coincided with and nurtured a festering golden age for paparazzi photographers and celebrity bloggers, sparked by the emergence of the internet and the calamitous drama in the lives of stars such as Lindsay Lohan and Paris Hilton. Before camera phones were ubiquitous, the photographers with the telephoto lenses were the only way into the intimate lives of these women, whether they were stopping at the gas station for cigarettes or being dropped off sobbing at the L.A. County Jail.

But Bynes, in a curious twist of fate, ended up being her own most persistent photographer. The paparazzi hounded her too, capturing her at the airport, wearing ratty nylon blond hair and with strange symbols etched into her arm, pretending to talk on a phone that she held clamped to her ear, just days before her hospitalization. And they were present when she stumbled out of Manhattan NYPD Central Booking in 2013, her eyes shrouded by fake bangs, like a kid in an ill-fitting Halloween wig. The most damning evidence of Bynes’s unraveling, though, came from Bynes herself, via social media, tracked in real time by her 3 million followers.

From 2013 to 2014, the formerly squeaky-clean tween star, once described by The New York Times in 2002 as “Lucille Ball, Carol Burnett, and Gilda Radner rolled into one 16-year-old package,” called a host of different celebrities “ugly.” She opined about her new nose job. She posted seminude pictures of herself wearing torn panty hose, and heavily filtered, vacant-eyed close-ups. She told Rihanna it was her own fault that Chris Brown had beaten her. She claimed that unflattering paparazzi pictures of herself walking around New York were actually photos of an imposter posing as her. She accused her father of sexually assaulting her. She then retracted those claims, stating that the microchip in her head had made her make them, but that her father was the one who put the microchip there.

It’s these tweets, Bynes said in an interview with Paper magazine this week, her first substantial profile in almost a decade, that she most regrets. “I’m really ashamed and embarrassed with the things I said,” Bynes told the writer, Abby Schreiber. “I can’t turn back time but if I could, I would. And I’m so sorry to whoever I hurt and whoever I lied about because it truly eats away at me. It makes me feel so horrible and sick to my stomach and sad.” She adds, “Everything I worked my whole life to achieve, I kind of ruined it all through Twitter.” She quickly notes that it’s not Twitter’s fault; it’s hers.

But it’s not quite so simple. Bynes’s breakdown, like Spears’s, became a chaotic, addictive sideshow. And gossip bloggers and news sites profited from the public disintegration of a vulnerable young woman who, since the age of 7, had been extremely exposed. Four years later, Bynes is reckoning frankly and openly with how she behaved in that moment. Is anyone else doing the same?

The Paper profile is revealing in a handful of ways. First, there are the photographs, the medium through which Bynes’s decline was so visibly and persistently chronicled. In the cover photo, the fashion student and aspiring designer is dressed conservatively, in a checked blazer and jeans. Bynes seems cautious in most of the images, as she did a year ago in her first broadcast interview since her hospitalization, a strange and uncomfortable video in which the YouTube personality Diana Madison asked Bynes to rank other former child stars in order from “hot” to “not.” She smiles in only one of the Paper photos, as a stylist adjusts an elaborately beaded blouse underneath her hair. Bynes looks almost like her pre-2010 self there: animated, wholesome, and at ease.

To the question of what exactly happened to her, Bynes swats away the armchair diagnoses from online authorities that she suffered from some kind of psychotic break or mental-health disorder, stating instead that she had been smoking marijuana since the age of 16, and that abusing Adderall for weight-loss purposes precipitated her breakdown. On the set of the movie Hall Pass in 2010, she recalls, “I remember chewing on a bunch of them and literally being scatterbrained and not being able to focus on my lines or memorize them for that matter.” She was replaced in the role by Alexandra Daddario—the first sign of trouble in Bynes’s career.

What also seems apparent, though, is that Bynes’s entire life on-screen left her with a kind of body dysmorphia that drugs made worse. Seeing herself dressed as a boy in the 2006 movie She’s the Man, she tells Schreiber, sent her into “a deep depression” for more than four months. A screening for Easy A, her last film appearance, prompted a drug-induced fit of self-loathing. “I literally couldn’t stand my appearance in that movie and I didn’t like my performance,” she says. “I was absolutely convinced I needed to stop acting after seeing it.” She announced that she was retiring from acting on—where else?—Twitter, only to retract the claim shortly after.

It was at this point, in 2010, that Bynes began the process of dismantling the public facade that years of TV shows and teen movies and red carpets had built. If Spears’s head-shaving moment forced America to see what the weirdness of child stardom and a life of being physically dissected really look like, Bynes’s Twitter account did the same thing. Her unfiltered thoughts were dark, jarring, comically absurd. She constantly assessed people by whether they were pretty enough, young enough, still hot. She disparaged public figures from Miley Cyrus to Barack and Michelle Obama as being “ugly.” To Jenny McCarthy, she wrote, “I’m 27, u look 80 compared to me!”

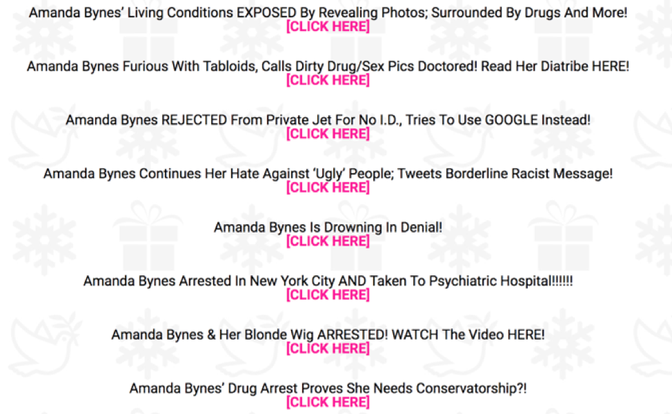

The response from bloggers and news sites at the time was to treat Bynes’s outbursts as a good joke, just like her increasingly strange appearance. “If a picture is worth a thousand words, then any recent snapshot of Amanda Bynes would just say ‘WTF’ 1,000 times,” an E! post from 2013 compiling “her biggest Twitter feuds” reads. The gossip blogger Perez Hilton, who documented Bynes’s misadventures relentlessly, similarly rounded up her “most bizarre yet entertaining tweets.” He also posted a list of recent headlines on his site relating to Bynes, which illustrates the kind of obsessive scrutiny that Bynes faced at the tail end of her acting career.

Bynes, in her Paper profile, apologizes wholeheartedly. She takes ownership for making decisions that led to behavior that she says is entirely out of character for her. Having been sober for almost four years, she wants people to learn from her experiences. “Everybody is different, obviously,” she says, “but for me, the mixture of marijuana and whatever other drugs and sometimes drinking really messed up my brain. It really made me a completely different person. I actually am a nice person. I would never feel, say, or do any of the things that I did and said to the people I hurt on Twitter.”

Spears’s decline coincided with the era of Peak Paparazzi; Bynes’s coincided with Twitter’s emergence as a self-publishing platform. And while contemporary celebrities are decidedly savvy about employing their social-media presences for optimum self-promotion, stars in 2010—particularly fragile stars—hadn’t figured out how to navigate the thorny question of how much to share online. Bynes, The Washington Post’s Caitlin Dewey wrote in 2014, was tapping into an old tradition of autobiographizing with her Twitter account, writing and rewriting her posts to try to best define the self that she felt like presenting. With Bynes, Dewey wrote, “the erraticism and oversharing come with no guarantee she’ll be okay—which is, perhaps, why more than 3 million people are reading.”

It could also be the reason the responses to Bynes’s first teetering steps toward a return to public life have been so warm. “This is the comeback we’ve been rooting for,” one viral tweet read. “Pictures of Amanda Bynes shouldn’t have such an emotional impact on me but here I am,” the figure skater Adam Rippon tweeted. On the Reddit board r/blogsnark, users praised Bynes’s honesty and how “healthy and happy” she seems to be. “I’m ecstatic that she’s doing well!” one commenter wrote. “Growing up as a child performer can be rough, but seeing her turn it around is wonderful.”

The positivity that Bynes’s Paper profile has been met with is a sign of the genuine hope that people can recover from addiction and mental-health issues. It hints at how much Bynes’s film and TV performances still mean to many of her fans. But it also seems to signal a recognition that she wasn’t treated fairly in the first place as a woman undergoing a profound breakdown in the public eye. At the height of Bynes’s fragmentation, she seemed to agonize over the self she was presenting, constantly deleting and posting thoughts and pictures to try to control how she was seen. But what she was inadvertently providing was more content to be carved up for consumption by onlookers relishing the spectacle and bloggers exploiting it for clicks.

Since 2008, and 2014, many writers and commentators have honed their sense of empathy when it comes to recognizing celebrities in crisis, enabled by figures, such as Bynes, who speak frankly about what happened to them. In this moment, popular culture is starting to revisit how women have historically been treated in the media, starting with Monica Lewinsky. Bynes’s tentative steps toward a comeback present an opportunity for the same kind of introspection.