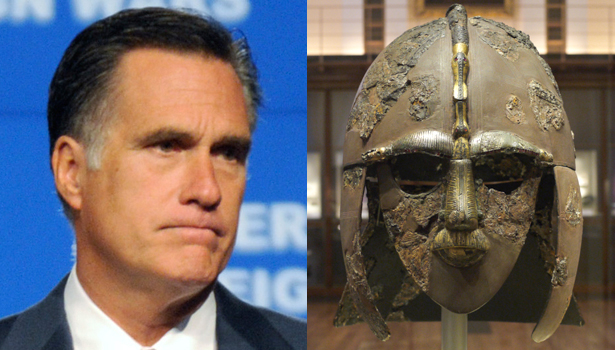

Sorry, Romney: Neither America Nor the U.K. Are 'Anglo-Saxon' Countries

The term is a long-abused misnomer for England, and fewer than 9 percent of Americans identify English ancestry anyway.

The term is a long-abused misnomer for England, and fewer than 9 percent of Americans identify English ancestry anyway.

When a Mitt Romney foreign policy adviser reportedly told London's Daily Telegraph, in advance of the candidate's trip to England, "We are part of an Anglo-Saxon heritage, and he feels that the special relationship is special ... The White House didn't fully appreciate the shared history we have," the comment sparked exactly the sort of campaign mini-controversy you might expect. Dogwhistles about Barack Obama's race and partial African heritage brought some of the 2008 campaign's ugliest moments, and "Anglo-Saxon heritage" could be interpreted as code for "white." The entirely foreseeable firestorm was followed by a similarly foreseeable Romney spokesperson's insistence that "If anyone said that, they weren't reflecting the views of Governor Romney or anyone inside the campaign."

It's worth forgoing the back-and-forth and pausing for a moment to take the comment at face value. Presumably, whoever said it wanted to highlight the "shared history" and cultural common ground between the United States and its former colonial master, which is tough to dispute. But you don't actually have to search out possible dogwhistles to find something wrong here: neither the U.S. nor the U.K. are really "Anglo-Saxon" countries. The term, often misused, actually describes two small Germanic tribes to which few Americans or Britons are directly linked. Don't look for Obama reelection strategist David Axelrod to tweet in umbrage over the mistake, but if you're the kind of person who votes on iron age historical accuracy, then read on.

The first person to apply the Anglo-Saxon label to Britain was a Benedictine monk named Bede, whose sweeping and long-definitive ethnography of eighth-century England was about as precise and scientific as you'd expect for the era. Bede's history declared that Britons descended from two Germanic tribes and one Dutch: the Angles, the Saxons, and the Jutes. But these migrants only started moving in after the Roman Empire's fifth century withdrawal, and anthropologists today do not seem to consider their impact as nearly so definitive as Bede did.

Anthropologists have disproven some of Bede's key claims, which long supported the idea that England is inherently Anglo-Saxon. Bede says entire German regions emptied onto the British isle, but today it looks like only perhaps 10,000 to 25,000 Angles and Saxons crossed over during the centuries of migration. These migrants settled in among the millions of people who were already there, ruling over parts of the island until the eleventh century Norman invasion.

The idea that Anglo-Saxon invaders defined or even significantly influenced British genetics has been "widely discredited," according to National Geographic, which quotes an archaeologist named David Miles. "Probably what we're dealing with is a majority of British people who were dominated politically by a new elite," Miles told the magazine. "They were swamped culturally but not genetically." It seems that Anglo-Saxons represented an elite minority, not the country in its entirety, and one that did not rule permanently.

Even their cultural influence declined with the 1066 conquest by Normandy, today a region of France. The new Norman rulers transformed England and ejected the old Anglo-Saxon elite, many of whom fled the country entirely. And so the Anglo-Saxon era ended, four or five centuries of rule that ended a thousand years ago and did not appear to make a lasting or substantial impact on British genes.

So, Anglo-Saxon is a bit of a misnomer, but even if we look past that and just accept the term as a colloquialism for the English people who were long ago ruled by Angle and Saxon lords, the idea that the U.S. and U.K. share an Anglo-Saxon identity still isn't really accurate. The 2001 U.K. census found that 85 percent of the country is ethnically "white British," which includes the Irish and Scottish whose forefathers were never under Anglo-Saxon rule.

And, though the United States began its history as an English-speaking colony of Britain, and has retained much of the English political and legal systems, it's not really an ethnic English country anymore. America's population has exploded by a factor of over 100 since declaring independence, much of that growth coming from slavery and immigration, neither of which drew heavily from England. In the 2000 U.S. census, only 8.7 percent of Americans identify their ancestry as English, which is ranked fourth behind German, Irish, and African-American.

It is true that Angle and Saxon raiders are a significant part of English history, just as British rule is part of American history. But nations and histories are bigger than their ruling classes. The Britons also ruled for a time over India, which though obviously different from America in many ways, also retains an English-style government and legal system, an English-style free market economy, the English language, and a close political alliance with its former master. But neither America nor India is anywhere near majority-English, as modern-day England does not appear to be ethnically Anglo-Saxon.

We don't really know what the Romney adviser meant when he referenced the "shared ... Anglo-Saxon heritage," if he even said it, but he wouldn't be the first person to overstate the influence of these long-gone Germanic tribes. On the off chance that anything productive comes out of this micro-scandal, maybe a slight corrective to the 1,200-year-old Anglo-Saxon misnomer will be one of them.