The Masterpiece No One Wanted to Save

Censored and then forgotten, Anatoly Kuznetsov’s Babi Yar, about the Nazi occupation of Kyiv, is again painfully relevant.

“There is no possible way of responding to Belsen and Buchenwald,” Lionel Trilling wrote in 1948. “The activity of mind fails before the incommunicability of man’s suffering.” The crimes of both the Nazi and Soviet regimes in the 1930s and ’40s defied all precedents of analysis and feeling. No ism could account for them; no wisdom could make them bearable. Though inside the stream of history, they seemed to belong to a realm of occult, pure evil. Today we’re drowning in art and scholarship about Europe’s terrible 20th century, but for contemporaries of the events, there was no language.

This silence—fear, shame, denial, simple inarticulateness—was broken soon after the war by the emergence of a new prose genre: the literature of witness. If the crimes could not be comprehended, they could at least be told—by victims and survivors, in subjective first-person voices, all the more authoritative for their lack of rhetorical flourishes and theological frames: Primo Levi’s Survival in Auschwitz and its sequel, The Reawakening ; Anne Frank’s diary; Elie Wiesel’s Night ; Charlotte Delbo’s trilogy, Auschwitz and After ; Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago; and, in the 1990s, I Will Bear Witness, the Dresden diaries of the German Jewish scholar Victor Klemperer. These and a few other books now comprise a European canon of the worst that human beings have done and suffered.

That Babi Yar, by the Russian Ukrainian writer Anatoly Kuznetsov, never joined the list is a strange omission with a story of its own. The book’s subject, the Nazi occupation of Kyiv, and its literary qualities make Babi Yar every bit the peer of the canonical works of witness. Its fraught journey to publication half a century ago, and now to a reissue (with an introduction by Masha Gessen) amid the Russian assault on Ukraine, only adds to its power as enduring testimony. The book’s very typography carries the scars of its struggle to tell the truth.

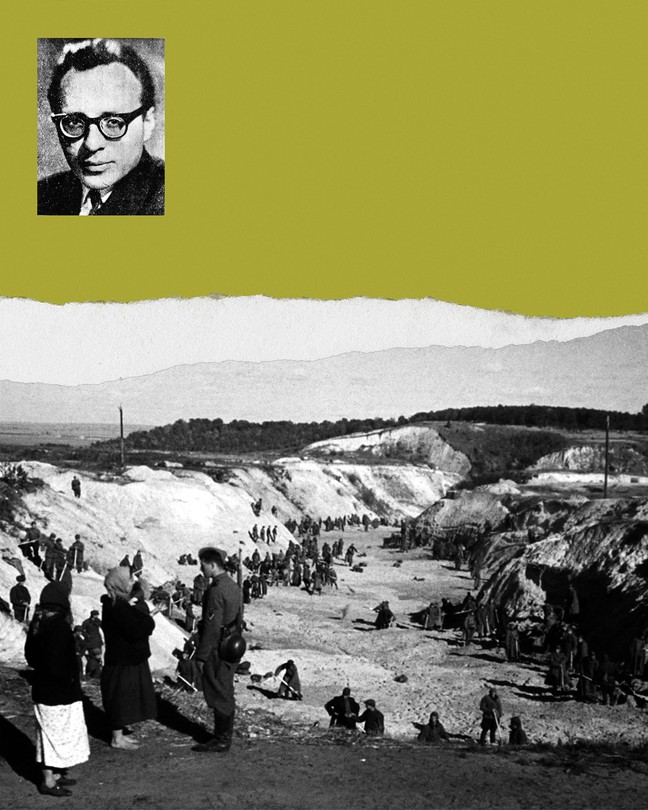

Born in 1929, Kuznetsov lived on the outskirts of Kyiv with his Ukrainian schoolteacher mother and his grandparents (his Russian father, a policeman, abandoned the family) in a simple house with a garden. Close by, amid woods and cemeteries, was a long, steep ravine, called Babyn Yar by Ukrainian locals, where Kuznetsov and his friends played in the stream that trickled along the bottom. He was 12 when the Germans arrived, in September 1941. On September 28, they ordered Kyiv’s Jews to report to the rail station near Babyn Yar the next day—the rumor was that the Jews would be deported to Palestine. At home, the boy and his grandfather heard the steady rattle of machine-gun fire from the ravine. For two days the shooting never let up, and it continued sporadically for the next two years as the ravine became the grave of more than 100,000 people—first Jews, then Roma, Soviet prisoners of war, Ukrainian nationalists, and anyone unlucky enough to be taken there—until the Red Army drove the Nazis out of Kyiv in November 1943.

Around the time of the city’s liberation, Kuznetsov, now 14, began writing down everything he’d seen and heard during the occupation and war. “I had no idea why I was doing it,” he later wrote; “it seemed to me to be something I had to do, so that nothing should be forgotten.” When his mother found the notebook, she wept and urged him to one day turn it into a book.

Kuznetsov came of age with an abiding antipathy toward the Soviet regime, but he was willing to make compromises to succeed as a writer. In the 1950s, he joined the Communist Party and moved to Moscow; in 1960, he became a member of the Writers’ Union. His fiction was hugely popular, and he accepted heavy censorship as the price of fame. All the while, with his childhood notebook in hand, he was gathering official documents and Kyiv inhabitants’ personal memories for a novel about the Nazi occupation. On a visit to his hometown, he interviewed a woman named Dina Pronicheva, who had been one of just a few survivors to crawl out of the mountain of nearly 34,000 Jewish corpses in Babyn Yar, victims of those first two days of shooting, the largest single execution of the Holocaust. Kuznetsov located other witnesses too—prisoners of war, slave laborers.

But as he worked on the novel, he found himself stymied by the familiar Soviet rules of socialist realism (“what ought to have happened”), which required a stark contrast between Nazi villains and Soviet saviors. The result rendered “the truth of real life, which cried out from every line written in my child’s notebook … trite, flat, false and finally dishonest.” Kuznetsov had seen up close two regimes whose monstrous deeds and lies converged, and too many desperate or merely cruel Ukrainians doing unforgivable things. He threw out the ideological stylebook and began to write as though he had to answer for every word.

In 1967, at the end of a brief liberalizing “thaw” between the reigns of Stalin and Brezhnev, and after party censors cut a quarter of Kuznetsov’s manuscript, Babi Yar: A Document in the Form of a Novel was published in Moscow. The subtitle is misleading. The first sentence announces: “This book contains nothing but the truth.” And yet so much of the truth had been excised (above all, the “anti-Soviet stuff”) that Kuznetsov tried to withdraw it, in vain. Its revelations nonetheless caused a sensation in the U.S.S.R. and beyond.

Knowing that the original manuscript’s discovery could get him arrested, he photographed its pages and then buried it in the ground. After the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, in 1968, Kuznetsov resolved to abandon his country at any price. The next year, he agreed to inform on other Soviet writers and in exchange won permission for a visit to England on the pretext of researching a novel about Lenin. In London, Kuznetsov gave his KGB minder the slip and, with the rolls of 35-mm film sewn into the lining of his jacket, presented himself to a Russian-speaking Daily Telegraph journalist as a defector.

In 1970, the complete version of Babi Yar was published in English, with the censored parts restored in boldface and even more anti-Soviet passages, written between 1967 and 1969, added in square brackets. This typography allowed readers to trace in minute detail the Soviet erasure of history, along with Kuznetsov’s development from personal memoirist to historical witness. The author’s name on the English edition was now A. Anatoli. “I’m making an absolutely desperate effort to turn myself into another person,” he explained to the CBS interviewer Morley Safer, gazing down morosely through Coke-bottle glasses, as if the effort was already doomed. In the freedom of the West, Kuznetsov published no new work; perhaps he needed the repressive Soviet atmosphere for inspiration. A nonperson in the Soviet Union after his defection, he never became well known in the West, and died of a heart attack in London in 1979 at age 49.

Babi Yar enjoyed brief fame, but soon descended into obscurity. It is little discussed in Russia and Ukraine, perhaps because it delivers unwelcome truths about both countries. The book is fiercely candid about Soviet crimes and Red Army failures during the “Great Patriotic War”; it’s also clear-eyed about the extent of Ukrainian collaboration, even as it vividly evokes Ukrainian suffering.

More than half a century after Babi Yar’s first appearance, it’s impossible to read the book without replacing German artillery with Russian missiles, the ravine in Kyiv with the mass graves in Bucha and Izyum. We learn that German troops shit on the floors of houses they’d occupied, just as Russian troops have done. Some Ukrainians, we now know, have become refugees twice in 80 years. Jewish survivors of 1941 were killed during Russian attacks in 2022. Painfully relevant again, Babi Yar might at last find the wide readership it deserves.

In the literature of witness, what makes Babi Yar both distinctive and elusive is the ambiguity of the situation it depicts. Where other Holocaust memoirs are set in concentration camps that enclose victims and killers, Babi Yar focuses on ordinary people in an occupied city, most of them neither Germans nor Jews, some complicit in evil, some avoiding or resisting it, all trying to survive the horror. The Nazi mass murder of Jews for which Babyn Yar and Babi Yar are known is described in only 20 pages, near the start of the book. This description from inside the ravine, based on Kuznetsov’s interviews with Dina Pronicheva, is unbearably specific:

The Ukrainian policemen up above were apparently tired after a hard day’s work, too lazy to shovel the earth in properly, and once they had scattered a little in they dropped their shovels and went away. Dina’s eyes were full of sand. It was pitch dark and there was the heavy smell of flesh from the mass of fresh corpses.

The censors’ cuts elided the participation of Ukrainians in the crime. As for the final detail, also cut, perhaps it was too much for Soviet sensibilities.

Between shootings, exhumations, air raids, and acts of cannibalism, some of the most powerful moments are small ones, featuring the everyday characters who are the book’s main concern. The narrator’s Ukrainian grandfather, a poor laborer, hates the Soviets. Memories of Stalin’s murderous famine of 1932–33 are still vivid. In quotations butchered by censors in 1967, the old man initially welcomes the arrival of the Nazis: “And those people who have got used to working with their tongues and licking Stalin’s arse—the Germans will get rid of them in no time. Praise the Lord, we have survived Thy ordeal, that Bolshevik plague! ” When Kyiv’s Jews are ordered to assemble—right after a series of tremendous explosions and fires in the city, which some of the population blames on Jews but which are in fact a departing act of sabotage by the Soviet secret police—the boy starts thinking like his grandfather. “Let ’em go off to their Palestine. They’ve grown fat enough here! This is the Ukraine; look how they’ve multiplied and spread out all over the place like fleas. And Shurka Matso—he’s a lousy Jew too, crafty and dangerous. How many of my books has he pinched! ”

Shurka Matso is one of the boy’s best friends. Nothing in this hellish tale is more disturbing than a 12-year-old’s sudden transformation into a Jew hater. Kuznetsov’s fidelity to his narrator’s point of view won’t let him soften the brutality of this betrayal. On the morning of September 29, the boy—who is forever dashing off to join a crowd of looters, check out a rumor, or try to sell limp cigarettes in the market—wakes up early to go watch the procession of Kyiv’s Jews toward the tram station not far from the ravine. He notices how beaten-down they look, carrying bundles tied with string and wearing necklaces of onions. These people are too poor, too old, too young, and too sick to have been evacuated. He has a change of heart:

How can such a thing happen? I wondered, immediately dropping completely my anti-Semitism of the previous day. No, this is cruel, it’s not fair, and I’m so sorry for Shurka Matso; why should he suddenly be driven out like a dog? What if he did pinch my books; that was because he forgets things. And how many times did I hit him without good reason?

A few pages later, when the shooting starts and the “deportations” turn out to be mass executions, the narrator’s mother and grandmother decide to hide a 14-year-old escapee from Babyn Yar. But before they can reach him, a neighbor woman gives him up to the Ukrainian police. For every act of courage and decency, there are far more of barbarism, and moments of mercy are rare. The narrator watches the boy being taken back to the ravine by a German soldier in a horse cart: “The soldier moved the hay aside to make the boy more comfortable. He put his rifle down on the straw, and the boy lay on his side resting on his elbow. He eyed me with his big brown eyes quite calmly and indifferently.”

These observations, so exact and free of sentiment, have the unadorned power of a child’s moral awakening. Telling the story through the eyes of the young Kuznetsov, which is not a narrative strategy but simply the truth, is a great advantage. Some passages read like a high-spirited adventure tale. Thanks to his age, the narrator can roam relatively unmolested around occupied Kyiv, scavenging for munitions or rotten potatoes (more than terror, the book’s strongest sensation is hunger), committing numerous “crimes,” and somehow escaping a Nazi bullet. Even his stint as an assistant to a buyer of old cart horses, who grinds the slaughtered animals into sausages for sale, is as fascinating as it is terrible. But these adventures end in flashes of insight, each harder to bear than the last.

Babi Yar reminds me in some ways of Huckleberry Finn. Just as Huck is able to see slavery with fewer illusions than the socialized grown-ups around him, the young narrator comes to realize that only luck separates him from the victims:

I don’t know whom to thank for my good luck: it’s nothing to do with people; there is no God, and fate, that’s just a pound of smoke. I am simply lucky.

It was purely a matter of luck that I arrived in this world not a Jew, not a gypsy, not old enough to be sent to work in Germany, that bombs and bullets missed me, that patrols didn’t catch me.

The emptiness and silence of this universe nearly suffocate him, but he’s also allowed a glimpse of solidarity with suffering. In the end he rejects all dictators, all ideologies, all better futures, all justified killings.

“No monument stands over Babi Yar,” begins Yevgeny Yevtushenko’s famous poem, written in 1961 after his friend Anatoly Kuznetsov brought him to Kyiv and showed him the ravine near his childhood home. The history of Babyn Yar is repeated erasure. First by the retreating Nazis, who tried to burn the human evidence of their crimes. Next by the victorious Soviets, whose ideology refused to recognize the Jewish essence of the Holocaust: They twice filled in the ravine to bury any memory of the vanished Jews, and later built the subway station, television center, and apartment blocks that are still there. Then the censors tried to sanitize Kuznetsov’s account into a tale of Soviet virtue. Vladimir Putin’s regime continues to lie about this history, exploiting the Holocaust to justify Russia’s latest imperial war as one of “denazification.” Ukrainians, fighting for survival under an assault that includes Russian propaganda, have never fully reckoned with the complexity of their own tortured past. Today the site of the ravine is an incoherent mess, a desultory patchwork of historical plaques and Holocaust kitsch.

The monument that stands over Babyn Yar is Babi Yar. In telling the truth, the book also exposes lies of the past and present. In looking with a child’s amazement at the worst of humanity, it achieves a humanism without slogans or illusions. The boy’s voice finally becomes that of the writer who lived through it all and found words for the unspeakable: “I wonder if we shall ever understand that the most precious thing in this world is a man’s life and his freedom? Or is there still more barbarism ahead? With these questions I think I shall bring this book to an end. I wish you peace. [And freedom.]”

This article appears in the March 2023 print edition with the headline “The Masterpiece No One Wanted to Save.”

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.