One day is enough, Mrs Dalloway teaches us; one day contains everything. That was especially true for On Kawara, the Japanese-born American artist who turned each day into a monument. Day after day, for half a century, Kawara took his paintbrushes and, with the greatest economy possible, depicted nothing but the date on which he painted. May 11, 1969. December 3, 1978. August 13, 1995. Each one is a memorial, and a memento mori.

On Kawara: Silence, a quietly rapturous exhibition that opens this weekend at the Solomon R Guggenheim Museum in New York, showcases the career of an artist who used minimal means for maximum effect. The artist died last year while preparing this show – instantly transforming his sequential paintings from an open-ended feat to a closed structure – and I had expected, when the show was announced, that Kawara’s insistently spare art would feel funereal in the Guggenheim’s grand spiral. I was wrong; it is a joy. Like each of his date paintings, the exhibition is somehow awesome and modest at once. It reckons with the grandest questions of being and time, and yet feels lived in, comfortable, and winningly unpretentious. It brings cosmic time down to human scale, and then makes an individual life feel as broad as the universe.

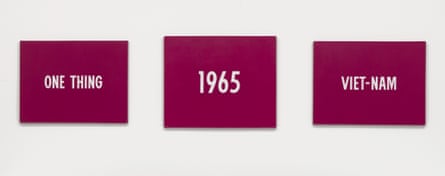

Kawara, who emigrated to the United States in 1964, made nearly 3,000 date paintings. He completed the first on 4 January 1966; on 12 January 2013, the latest date included here, he painted two. Each painting in the Today series was finished the day it was begun; if Kawara didn’t complete the work by midnight, he destroyed it. Each date is written in a typeface of his own devising, and in the language spoken where he found himself that day. (On 24 March 1976, in a German-speaking country, Kawara painted a supremely elegant umlaut.) If that language did not use the Roman alphabet, he wrote the date in Esperanto. Each painting is one of eight standard sizes, as small as a sheet of A4 paper or as large as 3.5 square meters, and uses one of three background colours: dark grey, blue, or sometimes red.

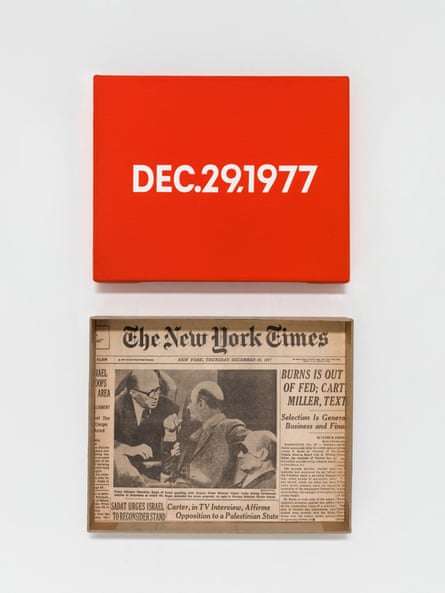

For many of the date paintings, Kawara designed cardboard containers – lined with a newspaper published on the day. Rarely seen, these boxes are presented here alongside the paintings, and they reinscribe the abstract date into the rumble of history, politics, and daily life. On 1 January 1970, Kawara completed a date painting, and we learn from the newspaper he glued into the box that the weather in New York was fair and cold, with a high temperature of 32F. On 20 January 1970, Kawara completed a date painting; President Nixon named a supreme court justice. On 26 January that year, Kawara completed a date painting; the Knicks beat the Celtics. The box for the painting of 2 February 1970, features dozens of obituaries. Bella Bergoffen, of Brooklyn. Giuseppe Lepore. Jennie Kaplowitz. Estelle Kohn. Kawara painted the dates of their deaths, and eulogised them.

Everyday or epic? Cosmic or mundane? Kawara’s date paintings are both – a perpetual abstraction, but also a system of self-portraits; a calendar, but also a diary; dates, but also days. It’s that indeterminacy, that constant oscillation between the quotidian and the universal, that gives his reticent art such force.

And then there is the blunt, underappreciated fact that for all his conceptual rigor, Kawara was a painter. The artist’s lack of “progress” throughout his career – the dates change, but the style remains the same for five decades – can be deceptive here; Kawara cared deeply about composition and craft, in a way that sets him well apart from other artists we lump under the umbrella of conceptualism. He mixed his own paint each day for the background colours, and they vary somewhat. The backgrounds were painted in multiple coats, the dates painstakingly lettered in the composition’s center. Each date painting took hours – hours, day after day, for 48 years. I think of Kawara in his studio in the East Village, or his hotel in Stuttgart or São Paulo, hunched over a desk or a table (he did not use an easel), and, with the meticulousness of a calligrapher, painting: April 18, 1972. January 13, 1978. June 9, 1982. May 31, 2000. They may be impassive, but there is nothing mechanical about them.

I have some reservations about the presentation of this show, which has been curated by Jeffrey Weiss, the museum’s senior curator. For this most chronological of artists, the spiraling ramp of the Guggenheim could have been transformed into a timeline: one life, one career, from beginning to end. Weiss, who collaborated with the artist on this presentation before Kawara’s death, hasn’t played it that way. The first two ramps are devoted to a single run of date paintings from 1970. But the top ramp has a single painting from every year from 1966 to 2014 – running down, not up, the spiral. Major date paintings, like the giant one Kawara completed upon the Apollo moon landing of 21 July 1969, are separated from the rest. And there are only 150 of them on view – which is a lot, yes, but also a lot less than 3,000.

Nevertheless, Kawara’s date paintings look fantastic in Frank Lloyd Wright’s often inhospitable temple. The show insists on the painterliness of his paintings – the careful arrangement of shapes on canvas, no two ever the same, over five decades – and not just their philosophical heft. And Weiss’s satisfyingly unponderous presentation shows Kawara as an artist with not just one but a number of daily practices.

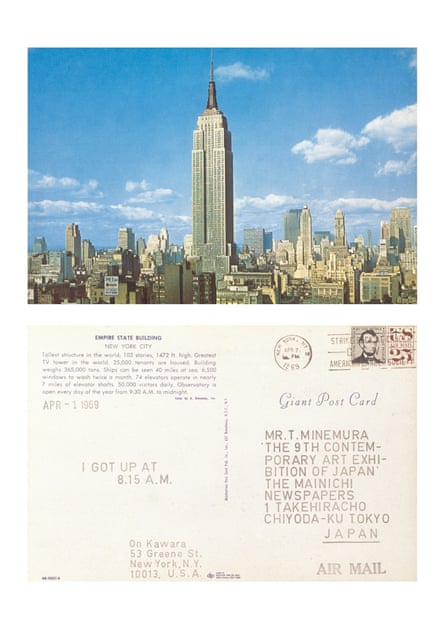

On most days from 1968 to 1979, he would send a postcard to friends and other arts professionals, stamped with the time he awoke. The 1,500 postcards here, depicting mundane sites like Yankee Stadium and the Eiffel Tower, prove he was a late riser. “I got up at 10:55am,” he announces on 15 September 1968, from Mexico City. The next day, 10:46am. One postcard depicts the Guggenheim itself, which Kawara sent to the art historian Lucy Lippard on 31 January 1970. “I got up at 6:15pm,” it reads – though he still had time to complete a date painting before midnight.

Another series notes all the people Kawara spoke to on every day from 1968 to 1979, typewritten and bound in binders. They serve as a reminder that Kawara, despite his reputation, was no recluse. The names include many of the noted artists of the period, including Robert Ryman, Daniel Buren, Sol LeWitt, and Hanne Darboven – but also otherwise unknown waiters and flight attendants and passersby, recorded the very same way. Kawara also photocopied maps and traced his daily peregrinations around New York, or his endless travel – in the pre-EasyJet era, he was constantly hopping from Berlin to Tokyo to Mexico City. For 30 years, from 1970 to 2000, he sent almost 900 telegrams with a single phrase: I am still alive.

So for many days of Kawara’s life we have not only a painting he made, but also an NSA-worthy record of the time he woke, the people he met, what he read, and where he went. And yet despite all of that information, offered in this moving and generous exhibition, he remains unknowable. There are no interviews, and essentially no photographs of him after his youth. He steadfastly refused to provide any biographical detail to scholars. He skipped attending his own exhibitions. We do not even know the exact dates of his birth and death. All we know is that he was born in 1932 and died in 2014 – and that On Kawara lived 29,771 days.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion