Philip Castle shows me into his front room to see the naked woman on her knees next to the family piano. The plaster sculpture is battered and fragile and turning yellow with time, but I would recognise those nipples anywhere. This is one of the nude statues that serve as furniture – and serve up drinks from their breasts – in the sinister, darkly funny opening scenes of Stanley Kubrick’s 1971 film A Clockwork Orange. “There was me, that is Alex, and my three droogs, that is Pete, Georgie, and Dim, and we sat in the Korova Milkbar trying to make up our rassoodocks what to do with the evening.”

In Kubrick’s pessimistic parody of British youth culture, Malcolm McDowell’s futuristic ultraviolent mod antihero sets the scene in voiceover as the camera pans back from him and his bowler-hatted, white-codpieced droogs, taking in one obscene statue after another, just like this one I viddied with my own eyes, O my brothers, in Castle’s house.

The curators of Daydreaming with Stanley Kubrick, an exhibition of art inspired by Kubrick with work by Mat Collishaw, Michael Nyman, Jane and Louise Wilson and many more, were understandably desperate to borrow it. “But it’s much too fragile to move,” says Castle, who offered up his own work instead to Somerset House in London, including a new portrait of Kubrick.

The story of how Castle came to own an original prop from the Korova Milkbar is a glimpse of the intellectual precision that made Stanley Kubrick one of cinema’s greatest auteurs, a perfectionist who sought to sculpt every aspect of a film – even its publicity.

Castle is a poster and album cover artist whose glossy, sometimes lurid airbrush painting style you have seen even if you don’t know it. His work ranges from the teardrop seeping from David Bowie’s shoulder blade on the cover of Aladdin Sane in 1973(in his hall hangs a print signed by Bowie) to portraying Pulp for the cover of their 1994 album His’n’Hers. He also created the hilariously over the top 1950s-style sci-fi poster for Tim Burton’s Mars Attacks.

Yet Castle’s finest hour – and perhaps the reason Bowie, Pulp and Burton later wanted to work with him – came right at the start of his career. As a graduate from the Royal College of Art at the fag end of its era as the home of British pop painting, he placed an ad for his illustration work in the Evening Standard. He got a call from none other than Stanley Kubrick’s publicist, inviting Castle to the director’s home north of London to discuss a poster for Kubrick’s new film.

Kubrick by this time was the most revered English language filmmaker in the world, celebrated for Lolita, Dr Strangelove and 2001: A Space Odyssey. He’d been living in Britain since the early 1960s and worked almost entirely from home. “He did everything in the house”, remembers Castle. “The striking thing was that all the doors were locked. They were all closed tight. They were great dog lovers and were scared stiff the dogs would run out and disappear. There were signs on everything: “Keep the door closed.” I suppose they had so many people going through. It was just curious, something you wouldn’t expect.”

The director looped up his latest film and they watched it, with Castle taking notes and making sketches in a Basildon Bond notebook that he still has. Its blue-tinted pages are filled with sketches of bowler-hatted ultraviolence – Kubrick’s new film was an icily ironic vision of stylised mayhem and dehumanising punishment adapted from Anthony Burgess’s 1962 novel A Clockwork Orange.

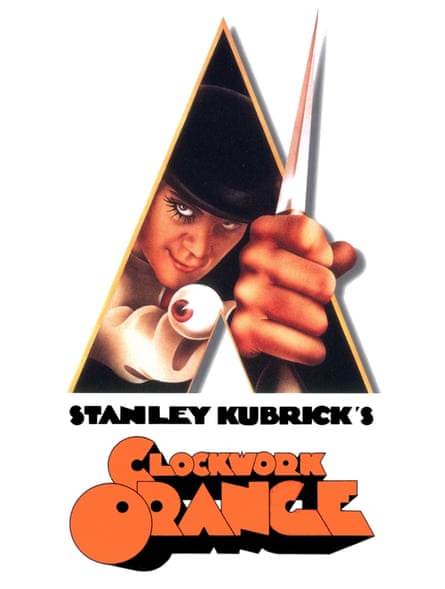

Castle’s little notebook shows, amazingly, that he came up with what is now seen as one of the classic film posters of all time practically then and there. One change was that he tried initially to fit his drawings of a vicious looking Malcolm McDowell wielding a glinting knife over a statue of a kneeling nude inside a giant letter A.

This becomes a pointed pyramid in the final version of the poster, which is painted in Castle’s hyper-pop hues against a white background with a slogan that pulls no punches: “Being the adventures of a young man whose principal interests are rape, ultraviolence and Beethoven.”

Eyes dominate the poster. As well as Alex’s staring deadly eye there is a floating eyeball alluding to his “treatment”, in which his eyes are pinned wide open as he is forced to watch violent films and Nazi propaganda. Yet what grabs you most is the shining blade that seems to leap forward in 3D. “It’s very pointy,” as Castle modestly puts it.

Kubrick wanted to shape every aspect of the film’s reception. “He had people going to the cinemas where it was going to be shown to make sure that the screens were clean,” remembers Castle. It was in the same spirit of absolute control that Kubrick sent his poster designer a statue from the Korova Milkbar so he could portray its dimensions correctly. On the decaying sculpture in Castle’s lounge rests a bowler hat. This too is an original prop from the film given to him so he could get the curve of its brim just right.

Art fills A Clockwork Orange. The sexist furniture in the Korova Milkbar is inspired by the art of Allen Jones. Kitsch nudes hang in the houses Alex and his droogs invade. He commits a murder using a marble sculpture of a penis. The visual world of the film is a grotesque homage to 1960s pop art and it is arguably the last great pop art masterpiece, an apocalyptic consummation of the consumer imagery of modern life that started with Richard Hamilton’s poster Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing? in 1956.

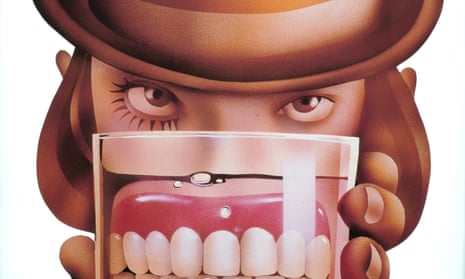

It was logical that a film so richly designed should also take art into the cinema lobby and on to the streets. Kubrick and his team published a mock newspaper, The Clockwork Times, for which Castle created some of his best works – lurid paintings of images from the film that dwell on its sex and violence. He has a photograph of his young family proudly posing under a huge billboard version of his poster on a London street. Yet the powerful publicity campaign in which he played such a central part backfired.

A Clockwork Orange was a hit but its reception was a real horror show. Tales of real-life “Clockwork Orange” gangs filled the British newspapers. Kubrick was accused of inspiring murder and his moral tale was accused of immorality. The director himself banned A Clockwork Orange from British screens. For a long time, until its rerelease in 2000, the sole image – apart from a few stills – that gave British film fans a sense of the style and menace of A Clockwork Orange was Castle’s potent poster.

He carried on working with Kubrick and the pair stayed friends, even after the director rejected his poster for Barry Lyndon in 1975 because it was too funny. Their closest collaboration was to come on the Vietnam war film Full Metal Jacket, for which Castle painted a helmet with a peace symbol and the scrawled words “BORN TO KILL”. Kubrick was interested in details such as how it would look in black and white in a single column of a local newspaper. Perhaps still scarred by the Clockwork Orange controversy, he also got Castle to try an alternative design for Asian markets because he was worried the US helmet “would get vandalised”.

Yet the artist’s memories of Stanley Kubrick are warm. One day the director phoned Castle out of the blue. What strange request would it be?

“He said: ‘Would you like to buy a puppy?’”

- Daydreaming With Stanley Kubrick is at Somerset House, London, until 24 August.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion