New York artist Leon Golub wrote an essay about art in 1986. “Artists manage extraordinary balancing acts,” he wrote, “not merely of survival or brinkmanship but of analysis and raw nerve.”

That last phrase explains his entire career in two words. Now, they are the title of a sprawling exhibition called Leon Golub: Raw Nerve, which opens this week at The Met Breuer. Over 45 artworks from 1940 to 2004 show the darker side of politics. There are paintings of dictators, terrorism, interrogations and beheaded victims from the Vietnam war.

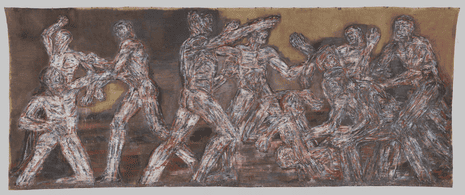

The exhibition starts with Golub’s masterpiece Gigantomachy II, a 25ft mural of nude men fighting, from 1966. “This artwork inspired the show,” said the curator, Kelly Baum. “It’s a mashup of 10 men in an endless struggle – it’s unclear who is hero, villain or why they’re fighting – but there is violence and destruction.”

It sets the theme for the exhibition; violence, destruction and war. It comes from an artist and activist who was a member of the anti-war group, Artists and Writers Protest Against the War in Vietnam, in New York. “Golub’s paintings were a response to the brutality he saw in the media,” said Baum. “As an activist, his paintings represent the violence he was opposed to.”

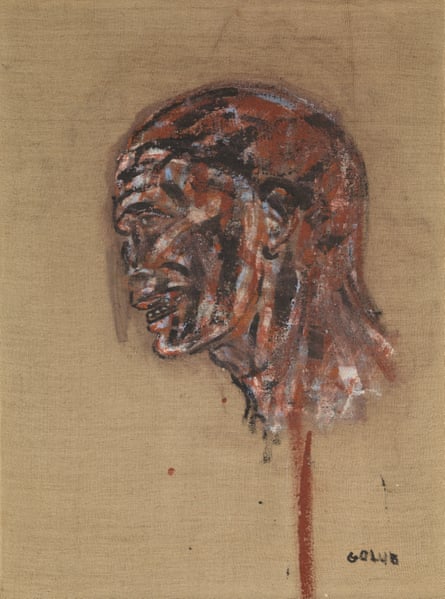

It’s easy to identify a Golub painting – often painted on unprimed canvas with thick brushstrokes in hues of terracotta, black and a muddy white. What helped him define his painting style was becoming part of the Monster Roster art collective in 1959, where artists were banded by “grotesque realism”, a figurative style that verged on the macabre. Most of the artists were mentored by Vera Berdich, a surrealist printmaker who taught at the Art Institute of Chicago, where Golub studied.

After spending several years living in Europe – from 1959 to 1964 – Golub returned to New York. Although he was always politically active, it wasn’t until 1970 that he merged his art with his activism in his Vietnam series. “He recognized the gap between being artist and an activist,” said Baum. “Golub redefined his art to bring art and politics together.”

That includes his horrific 1970 painting Vietnamese Head, which shows a beheaded man, presumably a victim of war. “It was an important transition painting, and it was then that he committed himself to representing acts of violence,” said Baum. “You can track his political commitments and concerns through his art.”

Golub began a series of political portraits that included Cuban leader Fidel Castro, former president Richard Nixon and Vietnamese leader Ho Chi Minh. “He painted, popes, mayors, generals, dictators and presidents who behaved badly,” said Baum. “He painted them all.”

The exhibition also features lesser-known characters, like Ernesto Geisel, the Brazilian general who led his country during the military dictatorship. “Golub represents him in many paintings over 15 years based on photos he saw in the media, from young to old,” said Baum.

Though Golub’s paintings were often controversial, that was precisely the point. “He wanted to get a rise out of people,” said Baum. “He used the word ‘contact’ a lot and he painted his characters to look back at you.”

But where would his paintings be without politics? They certainly wouldn’t have the same fire and fury. “Golub once said after the Vietnam war he had an artistic crisis,” said Baum, “because so much of his work was tied to the war and he wasn’t sure the direction his art should take after.”

In the 1980s, Golub looked to hidden government operations, terrorism and urban street violence for inspiration. Some paintings showed nudes being questioned by the police; others showed torture chambers and one man hanging from his feet being kicked by a soldier. But not all of them were so straightforward.

In 1986, Golub created Two Black Women and a White Man, which plays with power roles. “We don’t know who they are, but there is real force and power in these women,” said Baum. “The man is looking away from them with a creepy grin, and you’re left to imagine what’s happening.”

There are paintings of political interrogations and a series called Horsing Around, which followed misogynistic mercenaries as they sexually abuse women. The exhibition also includes Mr Amok, a painting from 1994, which shows a smiling, officer-like skull character. “It’s an allegorical representation of death,” said Baum, “he reimagines death as a biker who is prepared to unleash chaos to the world.”

Golub is an artist who takes us places we don’t always want to go, but shows us things we ultimately need to see. “His work is part-critical reflection and part-fearless audacity,” said Baum. “He was an artist, historian and an advocate for social justice – he wanted to suss out oppression wherever it existed and throw it all into his paintings.”