Art changed for ever in August 1914. We will soon be hearing a lot about the first world war as we hit the centenary of its start: the folly that led a peaceful world to destruction, the devastating descent into the quagmire of the trenches, the horrors of gas and barbed wire. The impact on art is less likely to fill anniversary commemorations.

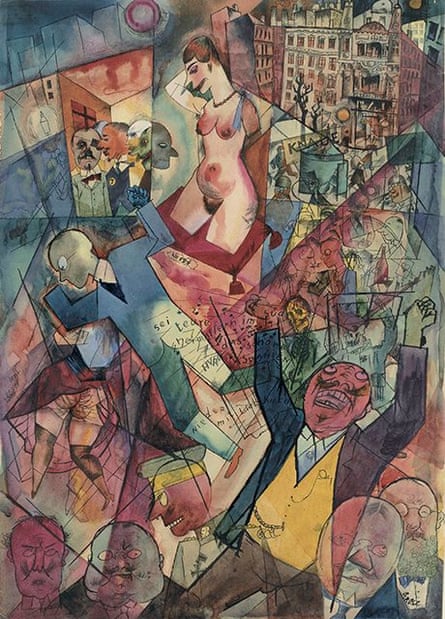

A remarkable exhibition at the Richard Nagy gallery on Old Bond Street, London, George Grosz's Berlin: Prostitutes, Politicians, Profiteers, reveals how brutalising and yet horribly energising that artistic impact was. Wounded veterans, maimed and disfigured, mingle with prostitutes, fat-cat capitalists, wicked old generals and decadent bohemians in Grosz's radically disillusioned art.

Born Georg Ehrenfried Gross in 1893, he anglicised his name as a protest against German nationalism in the first world war, in which he briefly served. His friend Helmut Herzfeld became, in similar fashion, John Heartfield. Both were turned into Marxist revolutionaries by the monstrosity of the war. Grosz was arrested in 1919 for participating in the Spartacist revolt led by Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht.

One quick way to see how the first world war changed art is to compare two of the most renowned works of the 20th century. The Dance by Henri Matisse was painted in the prosperous years before the war, in 1909-10. It is a thrilling, liberating, sensual masterpiece – yet deeply civilised, even in its primitivism.

By contrast, in 1917 Marcel Duchamp exhibited a urinal in an art gallery. This "readymade" called Fountain contemptuously urinates on the great tradition of western art. It reduces civilisation to a public toilet. It is no coincidence that it was first exhibited while so-called civilised nations were sacrificing their youth on the killing fields of the first world war.

Grosz and Duchamp were both, in their way, dadaists. This nihilistic art movement started in Zurich in 1916. It spat on war-torn Europe's claim to be civilised. Its angriest wing was Berlin dada. Cut-up newspapers and grotesque caricatures were hurled by the young Berlin dadaists at a social order they saw as murderous and cynical.

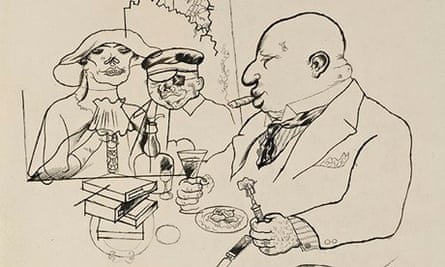

Grosz made some furious collages. But as his drawings at the Richard Nagy gallery attest, he was a hugely gifted draughtsman.

He can express his dada rage and hilarity in pen and paint alone. His pictures mash up the world of Berlin during and just after the first world war into a dazzling, comic, terrifying frenzy of flesh and faces.

The works here add up to a unique portrait of a city on the edge of revolution, as Berlin succumbs to the bitterness of defeat in 1918. You know, looking at these transfixing pictures of a great but tragic city, that nothing will ever be the same again. Not for Germany, not for the world, not for art.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion