In the art of Giuseppe Arcimboldo, the world of trees, fruit, vegetables and animals returns our curious gaze. Something sentient peers from the knotted bark of winter trees, the glassy orbs of fish, the cavernous mouth of an enraged beast. We collect and classify, observe and draw the forms of the natural world as if it were a helpless, unresisting set of phenomena, but Arcimboldo seems to believe that a power in the world stares back.

A gigantic stuffed elephant seal looms in the dark marble vestibule of the Natural History Museum in Vienna. It is a true monster, a prodigy of nature. This specimen was shot in the Falklands a century ago, but the mentality that finds it fascinating is far older. Just across Maria Theresien Platz in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Arcimboldo's 16th-century painting Water (one of his portraits of the elements) conveys the same wonder at the strangeness of life as provoked by that monster seal. A pearl earring dangles from Water's clam-shell ear. His mouth is a shark's maw, his nose the face of a moray eel, his hair fringed by bright red coral. He wears a crab for a breastplate and an octopus on his shoulder, an eel coiled about his throat and an echinoid crown. He is made up of 62 separate watery species, accurately observed yet combined without regard for scale or anatomical relationship - a turtle and frog among the crustaceans on his chest, a seal the same size as a neighbouring starfish.

This bizarre way of creating heads from an assemblage of natural objects has made Arcimboldo a modern icon. The surrealist movement in particular recognised him as a forerunner: his inclusion in the 1937 exhibition Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism at New York's Museum of Modern Art popularised a forgotten artist. Surrealist works such as Salvador Dalí's Portrait of Frau Isabella Styler-Tas, in which a woman is found in a mountain, or René Magritte's The Rape, which transposes a female torso on to a face, pay him explicit homage. How did a 16th-century painter come to be so modern? The answer lies in the shadowy undergrowth of the scientific revolution.

The history of scientific discovery is so often told as one of linear progress, the ascent of reason, that it's startling to realise how much of European science began in the bizarre ritualistic courts of the Renaissance, where curiosity was nurtured by rulers who supported the first modern scientists alongside alchemists, cabalists and hermetic philosophers. Perhaps the true father of science is the 13th-century Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II, "Stupor mundi" - wonder of the world - who conducted his own experiments including, it was said, sealing a man in a barrel and stationing observers to see if his soul rose up when he died. In Renaissance central Europe, Frederick's successors as rulers of the Holy Roman Empire sponsored conjurers and freaks, but also the great astronomers Tycho Brahe and Johannes Kepler, who produced the Rudolphine Tables, a new set of calculations of the positions of the planets named after their patron, the Habsburg Emperor Rudolph II. The art of Arcimboldo also comes from this time and place - he was employed by Rudolph and his father, Maximilian II.

He was born in 1526 in Milan, the city where Leonardo da Vinci had conducted most of his experiments and whose artists learned still-life painting from the bread, fish and glasses of water in The Last Supper. Leonardo had been dead seven years when Arcimboldo was born, but the Milanese nobleman Francesco Melzi inherited his notebooks and brought them home to Lombardy. Arcimboldo was fixated on his famous predecessor, and he aimed to turn himself into the Habsburgs' Leonardo. He must have heard stories about Leonardo's science, because he even claimed to have discovered a way to cross rivers where there were no bridges, which was one of the older man's stunts.

In so far as any of Arcimboldo's early works in Milan can be identified, they are unimpressive. But just as Leonardo had left Florence to shine at the court of Milan, Arcimboldo left Milan for the court of Vienna. Court artists tended to come from elsewhere. Having foreign artists on the payroll made a ruler feel cosmopolitan. In the 1560s, this minor artist from Milan relaunched himself at the court of Maximilian II as the ingenious Arcimboldo, designer of fantastic costumes and settings for tournaments, and inventor of bizarre heads.

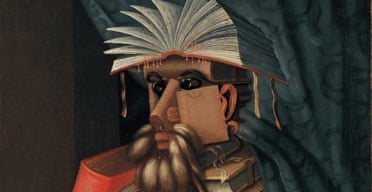

The heads made up of diverse objects were his real claim to fame, then as now. When you stand in front of his painting of a man made of books, you can imagine the delight at court in the artist's sharp wit. The Librarian has an open book on his head as a hat; his eyes are key rings, referring to his fussy custodianship of precious volumes; his beard is a set of feathers to deal with all that library dust; and the rest of him is formed by a staggering heap of books. Most brilliantly, his arm is a big white-bound volume with paper bookmarks for fingers. It's a dazzling performance: the ingenuity of Arcimboldo's paintings could be enjoyed as an outrageous game. In fact, The Librarian would have been recognised by its first audience as a cruel portrait of Wolfgang Lazius, court historiographer to Maximilian and a passionate book collector. There's a hardness to this painting and a seriousness, too: its courtly game is really a Hamlet-like questioning of reality. What is an individual? Is a book collector any more than the sum of his books?

Drawings by Arcimboldo suggest this was, for him, a real and pressing anxiety. The most troubled examples of his art that survive are the most intimate. In his self-portrait Man of Paper, you don't immediately notice what it is, then you see the curls and coils of thin paper that constitute his ruff, his robes and his unsmiling, bearded face. He is as ruthless with his own identity as with that of the bibliophile. Gloomiest of all in its sense of the fragile fiction of power, and most reminiscent of Shakespeare's tragedies, is his drawing of the coronation of the young Rudolph II at Regensburg in 1575. The ancient crown of the Holy Roman emperors is much too big for Rudolph's head, and he wears it with fearful unease.

Rudolph was to prove as tragic as Arcimboldo's portrait suggests - a depressive who buried himself in his art collection and scientific-magical interests, and let his empire descend into chaos. He moved the capital to Prague, to where Arcimboldo followed for a while, designing fantastical costumes for the tournaments Rudolph held to forget his cares. The emperor was a knowledgable collector whose tastes make the Kunsthistorisches Museum home to one of the great European art collections: near the Arcimboldo show, you can see the fabulous erotic scenes from Greek myth by Correggio and a self-portrait by Parmigianino, another of Rudolph's favourites.

This portrait brings us to the mysterious interweaving of art, science and the occult in Renaissance Europe out of which Arcimboldo's paintings grew. The 16th-century art chronicler Giorgio Vasari claimed Parmigianino was a student of alchemy: his self-portrait has an occult quality in the way it depicts the convex mirror into which the artist stares to take his image; the distortions of the glass stretch and contort the artist and the room. It is as if he is trapping himself in a mirror for all eternity. The picture is round like the mirror it depicts - that is, it doesn't look through art as if art were a window, but loses its way in the artistic process. Such eccentric turns are everywhere in 16th-century art, as precious mannerists rejected the reasonableness of earlier Renaissance painting in favour of fantasies and hobby-horses. In Florence, the studio of Francesco I de' Medici is a little room shaped like a treasure chest and decorated with scenes of metallurgy, pearl fishing and other technical subjects. It is a place to meditate on the marvels of nature and the intricacies of art; a place not to find scientific facts, but to revel in myths and fables. You could call this the mannerist style in science as well as art. The Habsburgs and other central European courts expressed this mannerist curiosity above all through their convoluted collections.

One of the earliest surviving items from these is a "shaker box" of green moss containing replica snails, insects and tortoises that move when the box is shaken. Another survivor is a wax portrait of Rudolph II, while a painting records a "Nile horse" - a stuffed hippopotamus - he had in his cabinet of curiosities. It must have been as awesome as the elephant seal you can still see in Vienna. Rudolph's collections made explicit the belief of the Renaissance that everything in nature is linked by resemblance and correspondence. According to this cosmology, the sublunar world is strictly hierarchical, with stones at the bottom and above them, in ascending order, plants, animals, human beings and angels. By the right use of talismans and charms, practitioners of "natural magic" believed, you might ascend to a higher link in the chain of being. This cosmology, rather than anything like modern classifications, shaped the early museums and survives in Arcimboldo's art. In his portraits of the four elements, Earth swarms with brown soil-hued beasts that crawl on the ground; Air is a squawking assembly of birds; Fire is made of heat-forged metals, fireworks, guns and cannon, a "firestone" and a blazing candle, its hair a bright bonfire. None makes sense in modern schemes of classification - the head of Water mingles vertebrates and invertebrates without any sense that they are different.

Arcimboldo's composite heads are archetypal objects from a cabinet of curiosities. Heads made of shells survive from such collections. These paintings hung with wax objects and stuffed beasts in the emperor's curious chamber. Arcimboldo was one of the first artists accurately to observe nature since ancient times, when Greek artists were famous for the verisimilitude of paintings that have long since vanished. His several sets of heads of the four seasons are meticulous, at their best almost miraculous, perceptions of nature. Eighty flora have been identified in the head of Spring, including dog rose and columbine, strawberries and spinach leaves, jasmine and nettles. In the most beautiful version of this composition, now owned by the Louvre, petals give the young man a fresh pink complexion, cabbage leaves wrinkle his shoulder, and nettles entwine his chest, all painted with a precision worthy of a scientific illustrator.

Yet heads composed of fruit and flowers, however accurately studied, would just be a gimmick if they did not possess something deeper. There is a formidable power in these seasons and elements. They are more than their parts; they are not mere optical tricks, but characters or personae. They are a bit frightening, for there is at their core a life force that verges on the demonic.

Arcimboldo's nature is superabundant. Even in abeyance, it is rich and full: in deepest midwinter, it is busy. His Winter is a twisted, gnarled tree stump, and yet, far from being denuded of leaves and life, it is encrusted with parasitic growth: ivy proliferates in the woody roots of its hair, its white lips are tree fungi, two lemons hang on a sprig. Veins bulge from its bark. In Spring, this old man is replaced by a young face pink and green with lewd vitality. The uninhibited brightness of the young world is almost painful - and this becomes still more unsettling in the face of Summer, whose ripe fruits form a mad, wild grin. Summer's laughing cherry eyes are heartless, unthinking, sublimely potent. The softer profile of Autumn seems wiser, savouring grapes and grains.

The year is a living creature that metamorphoses from one form to another through its abundant cycle. Each of these seasonal beings is alive and, more than that, conscious. These are nature gods, and they come from a place far more primitive than the classical sources studied by Renaissance humanists. Their supernatural charge has more to do with the harvest ballads and carnival masks of the peasants whose rites the emperor might observe on hunting trips than with his court librarian's ransackings of the Latin authors.

In the years that Kepler worked as court mathematician in Prague, he was distracted by a problem: he had to try to save his mother from being burned after she had been accused of witchcraft. Demons were real in Renaissance Europe. At the highest courtly level, Faustian magicians conversed with them: John Dee and Giordano Bruno, who frequented Rudolph II's court, were masters of elite magic, and Bruno was to be burned for it. Outside such circles, hundreds of women were killed in 16th-century Germany for supposedly consorting with devils. Arcimboldo's paintings evoke a demonic nature, in a world that believed in such forces.

Of all his cunning substitutions of natural forms for human anatomy - the elephant's ear that becomes the ear of Earth, the broken branch that is Winter's nose - by far the most brilliant and disconcerting are his many ways of giving nature eyes. The eye of Water is that of a sunfish: vast, round, glittering and dark. The eye of Winter is a knotty hole that leads deep into the tree's depths. Petals make Spring's eye. All these are windows on some sentient consciousness. This is why the paintings fascinate us - not because they are ingenious, but because they are uncanny. At the heart of their power is the conviction that unnamed beings look back out of the trees and fields, that the world watches, with a smile or grimace.

The very accuracy and objectivity with which Arcimboldo depicts fruit or fish anticipates a colder, deader sensibility. As natural history generated ever greater knowledge, the art of depiction became more clinical - until, by the 19th century, there were no more demons in the woods. In his monstrous, godlike heads, an ancient agrarian worship of nature has its last sinister fling.

In his final years, Arcimboldo, ennobled by Rudolph II, retired to Milan. Amazing his fellow artists with his title of Count Palatine of the Holy Roman Empire, he worked on a great painting to send to Prague: a portrait of Rudolph as the Etruscan rustic god Vertumnus. All Arcimboldo's other heads are portrayed in profile, but this potent natural deity faces us full-on. His berry eyes are surmounted by pea-pod brows, his nose is a pear, he has a horse-chestnut beard. He embodies the abundance the emperor brings to his lands. But I think he is, more than anything, the face an exhausted peasant might glimpse at the end of a long day's harvesting, peering back out of the misty sunset woods.

A sword from the Habsburg collections hangs behind glass in the Kunsthistorisches Museum. It has a blade of steel and a pommel of bright red coral, a substance that possessed magical, talismanic powers. Coral offered protection, hence its use in a weapon. It is hard for us to take such ideas seriously, but look from this treasure into the eyes of Arcimboldo's creations, and just for a moment the magic circuit is remade, the chain of being electric with possibility, the coral re-enchanted. Arcimboldo is at the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, until June 29. Details: khm.at