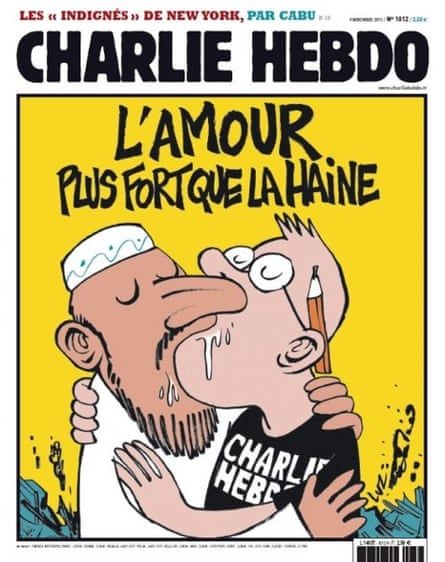

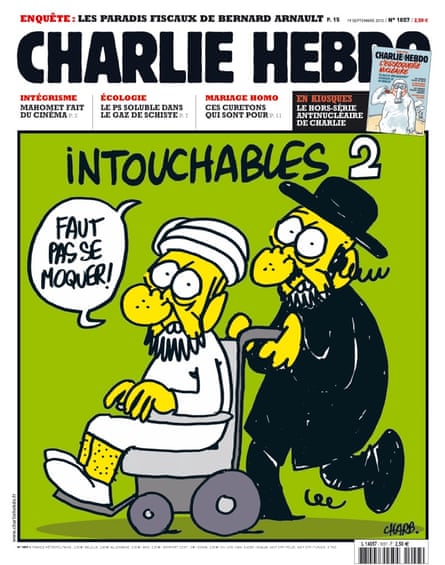

Satire and Islam do not sit well together, especially if the format is visual representation of the prophet Muhammad – and perhaps also the self-proclaimed caliph of Islamic State (Isis), now ruling swaths of Iraq and Syria, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.

Charlie Hebdo, the French magazine whose offices were attacked by gunmen in Paris on Wednesday, has published several controversial cartoons portraying the prophet, some in pornographic poses. Last October, it portrayed the jihadis of Isis as being opposed to Islam by displaying an image of a masked man cutting the throat of his kneeling, turbanned victim, who is saying: “I am the prophet, you brute.”

The killer replies: “Shut your mouth, you infidel.” The cartoon was captioned: “If Muhammad returned …”

Observant Muslims anywhere would be angered by such images. That is especially true of fundamentalist Salafis, who adhere to traditions laid down in 7th-century Arabia, or of the small minority who hold to the jihadi-takfiri world view espoused by Isis and al-Qaida. Their doctrines permit the killing of so-called apostates. But devout Sunni Muslims of all stripes avoid visual depictions of Muhammad or other prophets such as Moses or Abraham.

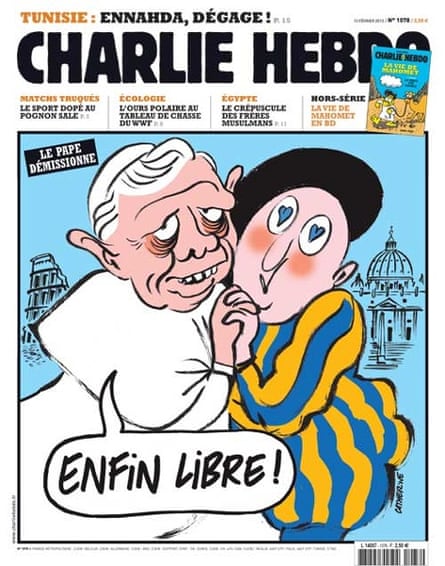

Islam is not unique. Judaism forbids the use of “graven images” and Christianity has at times frowned on visual representations of sacred figures, allowing only the cross to be depicted in churches.

The Qur’an does not explicitly forbid images of Muhammad, but several hadith (sayings and actions attributed to the prophet) prohibit Muslims from creating visual depictions of human figures. Traditionally, the concern has been that images may encourage idolatry, the scourge of the jahiliyya period of pre-Islamic Arabia.

The most common visual representation of the prophet Muhammad in Islamic art is by elaborate swirling Arabic calligraphy. The Qur’an is never illustrated.

The destruction by the Taliban in Afghanistan of statues of Buddha in Kandahar is a notorious example of the intolerance of images, part of the school of tawhid – usually translated as Islamic monotheism. Sunni disapproval of Shia Muslim shrines reflects this too. Shia are more flexible than Sunnis and display images of Husayn, the grandson of Muhammad.

The differences between the two main branches of Islam are often compared to those between Protestants and Catholics in the Christian world. Isis in Iraq has demolished shrines to Sunni or Sufi figures, while Shia mosques have also been destroyed – hence the Iraqi Shia militiamen and Iranian Revolutionary Guards protecting the revered Sayyida Zeinab shrine in the Syrian capital, Damascus.

In a cartoon published just before Wednesday’s killings, Charlie Hebdo portrayed Baghdadi, apparently based on a photograph of him preaching in a mosque after the capture of the Iraqi city of Mosul last June and his proclamation of a new caliphate. It sarcastically wished him “especially good health”.

In November 2010, the magazine’s office was hit by a firebomb and its website hacked after it announced plans for an edition with Muhammad as its chief editor, and the title page with a cartoon of him was posted on social media.