Ecoscenarios Combined - FOSSweb

Ecoscenarios Combined - FOSSweb

Ecoscenarios Combined - FOSSweb

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Ecoscenario: Arctic National Wildlife Refuge<br />

4/16/03 3:07 PM<br />

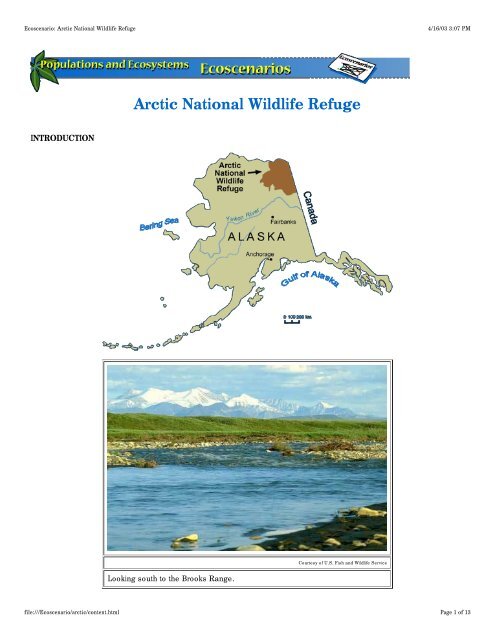

Arctic National Wildlife Refuge<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

Courtesy of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service<br />

Looking south to the Brooks Range.<br />

file:///Ecoscenario/arctic/content.html<br />

Page 1 of 13

Ecoscenario: Arctic National Wildlife Refuge<br />

4/16/03 3:07 PM<br />

The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge in the northeast corner of Alaska is one of the most pristine, undisturbed places<br />

on Earth. It covers 7,700,000 hectares (19 million acres). To the south is the rugged Brooks Range and to the north,<br />

the icy Arctic Ocean. The 600,000-hectare (1.5 million-acre) coastal plain is the most productive part of the refuge<br />

and the area used most by wildlife. This area is dominated by an ecosystem known as middle arctic tundra. The<br />

treeless landscape is flat and covered with low-growing plants.<br />

The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge is sometimes called America's Serengeti because of the number of animals that<br />

live here. Huge herds of caribou, as well as polar bears and musk ox, roam this vast plain. The Gwich'in<br />

Athabascan Indians have depended on these animal resources for over 12,000 years.<br />

Courtesy of Jon Nickles, U.S. Fish and<br />

Wildlife Service<br />

A caribou makes its way<br />

across the marshy arctic<br />

tundra.<br />

Courtesy of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service<br />

The coastal plain of the Arctic National Wildlife<br />

Refuge is pitted with ponds during the short<br />

summer.<br />

Two conservationists, National Park Service planner George Collins and biologist Lowell Sumner, recognized the<br />

unique nature of this ecosystem and began efforts to protect it in 1952. Federal protection started in 1960 with the<br />

establishment of the Arctic National Wildlife Range. In 1980, the U.S. Congress passed the Alaska Lands Act,<br />

renamed the area the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, and doubled the size of the protected area. The refuge is the<br />

largest designated wilderness in the National Wildlife Refuge System. It is administered by the U.S. Fish and<br />

Wildlife Service in the Department of the Interior.<br />

Congress created the refuge to protect the wildlife and habitats of this ecosystem for the benefit of people now and<br />

in the future. The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge and two parks in neighboring Canada have been proposed to form<br />

an international park. Many of the refuge's wildlife species are protected by international treaties.<br />

ABIOTIC DATA<br />

Frost, snowfall, and freezing conditions shape the tundra landscape in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. The<br />

extreme cold creates a layer of permanently frozen soil called permafrost. In May when the snow melts, the surface<br />

soil becomes waterlogged because water can't drain through the permafrost. The region becomes saturated with<br />

standing water and flowing streams.<br />

file:///Ecoscenario/arctic/content.html<br />

Page 2 of 13

Ecoscenario: Arctic National Wildlife Refuge<br />

4/16/03 3:07 PM<br />

Because the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge is so far north, entirely above the Arctic Circle, the growing season is<br />

short, only 50–60 days. During summer the Sun never dips below the horizon, but its long, slanting rays do little to<br />

heat up the air. Temperatures range from 2 to12°C (36 to 54°F). During winter the Sun never rises above the<br />

horizon. The noon sky looks like predawn. In winter, the temperature averages –34°C (–30°F).<br />

There is little precipitation in winter or summer. Yearly precipitation, including snow, is only 15–25 centimeters (6–<br />

10 inches). Wind is a major factor in this area and can blow up to 160 kilometers per hour (100 miles per hour).<br />

file:///Ecoscenario/arctic/content.html<br />

Page 3 of 13

Ecoscenario: Arctic National Wildlife Refuge<br />

4/16/03 3:07 PM<br />

Courtesy of ConocoPhillips Alaska, Inc.<br />

Snow still covers the windswept tundra in spring.<br />

Snow can benefit plants and animals because of its insulating qualities. Snow shelters plants and animals from the<br />

strong winds and protects the ground from disturbance. Small mammals, such as lemmings, make tunnels beneath<br />

the snow and avoid detection by predators.<br />

Courtesy of Environment Canada, Yukon<br />

Snow that falls in the winter often melts during May.<br />

The ground has two layers, an active layer and a permafrost layer. The top active layer is made of dead and partially<br />

decayed plant material. It is very wet because the water cannot drain through the permafrost below. The active layer<br />

is not considered true soil, because the plant material decomposes too slowly. The depth of the active layer<br />

changes through the season from 0 to 45.5 centimeters (0 to 18 inches). Below the active layer is permafrost, made<br />

file:///Ecoscenario/arctic/content.html<br />

Page 4 of 13

Ecoscenario: Arctic National Wildlife Refuge<br />

4/16/03 3:07 PM<br />

up of gravel, frozen groundwater, and finer material. Permafrost never thaws.<br />

BIOTIC DATA<br />

Biotic diversity in arctic tundra is generally low, food webs are simple, and populations usually have large<br />

fluctuations in size due to changing abiotic conditions. Plants and animals reproduce quickly in the short summer<br />

season.<br />

Because of the permafrost, plants in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge do not have deep roots. Only hardy plants<br />

that grow close to the ground can endure the effects of wind and cold temperatures. Grasses and sedges form in<br />

protective clumps called tussocks, and shrubs like willow and Labrador tea tend to be small species, under 1 meter<br />

(3 feet) tall. Because of the short growing season, many plants rely on asexual reproduction, such as cloning or<br />

budding, instead of flowering and forming seeds.<br />

Courtesy of ConocoPhillips Alaska, Inc.<br />

Sedges form tussocks on the tundra.<br />

Annual productivity, or the amount of energy provided by the producers in this ecosystem, is low. High metabolic<br />

rates of some herbivores burn most of the calories that are provided by the producers. Because there is a limited<br />

amount of energy to go around, food webs are relatively simple.<br />

Important producers in the tundra are moss, reindeer lichen, cotton grass, sedges, and willows. Tundra plants are<br />

adapted to grow in this harsh environment. Plants are low and tough, and leaves are small with a thick epidermis to<br />

file:///Ecoscenario/arctic/content.html<br />

Page 5 of 13

Ecoscenario: Arctic National Wildlife Refuge<br />

4/16/03 3:07 PM<br />

slow transpiration. Vegetation is dark green to red. This allows plants to absorb more of the limited solar radiation.<br />

Courtesy of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service<br />

Caribou give birth on the coastal plain during summer, most within Area 1002.<br />

Reindeer lichen is two different organisms living together in a symbiotic relationship. A photosynthetic alga lives<br />

inside a protective, structural fungus. This lichen has a treelike form and forms hummocks on the soil. Lichen<br />

serves as the major food of the caribou, especially during the winter. Caribou use a front antler tine and hooves to<br />

scrape snow cover away from lichen.<br />

Musk ox, polar bears, and caribou roam the coastal plain. They breed there in the summer where there is abundant,<br />

nutritious food and few predators. Standing water on the summer tundra is an excellent breeding ground for<br />

mosquitoes and black flies. Swarms of these insects are attracted to caribou herds and are such a nuisance that<br />

the caribou find it difficult to feed. Coastal breezes provide the caribou with some relief from mosquitoes and black<br />

flies.<br />

Courtesy of Environment Canada, Yukon<br />

How does temperature affect mosquitoes that bother the<br />

caribou?<br />

file:///Ecoscenario/arctic/content.html<br />

Page 6 of 13

Ecoscenario: Arctic National Wildlife Refuge<br />

4/16/03 3:07 PM<br />

Other animals found on the tundra include arctic foxes, snowshoe hares, lemmings, snow geese, and snowy owls.<br />

Many species of migratory birds nest on the marshy tundra during the short summer, leaving in fall to spend winter<br />

in warmer areas.<br />

Animals living on the tundra have adaptations to keep them warm. Weasels, rabbits, hares, and musk ox have two<br />

layers of hair, a soft, short layer close to the skin and a coarser, longer layer of guard hairs. Both layers work to<br />

keep warm air near the body and cold air and snow away. Some animals also have small ears, short legs, and<br />

short tails, which help reduce heat loss.<br />

Caribou have long, dense winter coats with hollow hairs for effective insulation. Both males and females have<br />

antlers, which are covered with velvet and fed by many blood vessels as they grow. Large concave hooves help<br />

caribou paw through the snow to reach buried lichens. Their broad hooves act like snowshoes and help them cross<br />

snow in winter and walk through soft, boggy pools in summer.<br />

Courtesy of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service<br />

The huge Porcupine Herd migrating across the tundra of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.<br />

Caribou migrate in huge herds from their wintering grounds in the Brooks Range taiga to calving grounds on the<br />

coastal plain over 640 kilometers (400 miles) away. They return yearly to the same calving grounds because there<br />

are few predators and high-quality food is abundant. Calving occurs during a 10 days in late May to early June. At<br />

this time, cows and calves are most vulnerable to predators and sensitive to any disturbances.<br />

Musk ox have roamed in the arctic since the Ice Age. They are well adapted for living on the tundra. To keep warm,<br />

they have a long, shaggy coat of guard hairs with shorter underfur that is extremely soft and fine. It can protect the<br />

musk ox in temperatures as low as –73ºC (–100ºF). The underfur, or wool (called qiviut), is shed in summer and<br />

collected by Alaskan natives to make woolen clothing.<br />

Musk ox travel in herds of 20–30 animals. When attacked by wolves, the larger adults form a circle with their horns<br />

facing outward. Young musk ox are protected in the middle of this circle. Extremely efficient at processing food,<br />

they need only one-sixth the food a similar-sized cow would use. In seasons when food is especially poor, they<br />

may wander into the wolves' range in search of food.<br />

file:///Ecoscenario/arctic/content.html<br />

Page 7 of 13

Ecoscenario: Arctic National Wildlife Refuge<br />

4/16/03 3:07 PM<br />

Courtesy of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service<br />

Musk ox huddle together for protection from<br />

predators and cold weather.<br />

Courtesy of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service<br />

Snow geese and other migratory birds nest in the<br />

Arctic National Wildlife Refuge during the short<br />

summer.<br />

Small rodents, like snowshoe hares and lemmings, are common on the tundra. Their populations are closely linked<br />

to their food supply and predator population. During summers when food is abundant, litters are larger and the<br />

populations grow. Larger populations of rodents support larger populations of predators, such as lynx and snowy<br />

owls.<br />

Many animals on the tundra have two color phases, one for summer and one for winter. Snowshoe hares and arctic<br />

foxes have heavier winter fur that is white and helps to camouflage them in snow. This fur is shed in summer to<br />

reveal darker fur. Some birds that remain in the arctic year-round, such as the willow ptarmigan, have white plumage<br />

in winter and darker plumage in summer.<br />

Wolves, foxes, and weasels are predators found on the tundra. A wolf pack will kill 11–14 caribou annually, usually<br />

during migration or in winter. Wolves will also attack musk ox, but they live out of the wolves' range most of the<br />

year. Arctic foxes are well adapted to live in the cold and do not need to hibernate in winter. They hunt small<br />

rodents and feed on abandoned kills of other predators.<br />

Polar bears are found in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, but spend most of their life on the ice flows in the Arctic<br />

Ocean. They feed primarily on seals, but will also eat fish, seaweed, grass, birds, and occasionally caribou. They<br />

return to the coastal plain in winter to hibernate. They spend so much of their life in the water and on the ice that<br />

they are considered to be marine mammals, like sea otters. They have thick, white fur that protects them from the<br />

icy water and camouflages them on snow and in the water. Wide paws and coarse fur on the soles of their feet give<br />

them traction on ice.<br />

ISSUES<br />

A long-standing issue in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge is whether the coastal plain should be developed for oil<br />

drilling. Other areas in Alaska, such as Prudhoe Bay, have already experienced oil drilling. Petroleum scientists<br />

have examined part of the refuge, called Area 1002, and predict that oil is there. When the U.S. Congress<br />

established the Arctic National Wildlife Range in 1960, they made provisions to authorize future oil development in<br />

the northern part. People have been debating the issue of oil and gas drilling in Area 1002 for almost 40 years.<br />

file:///Ecoscenario/arctic/content.html<br />

Page 8 of 13

Ecoscenario: Arctic National Wildlife Refuge<br />

4/16/03 3:07 PM<br />

Courtesy of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service<br />

A developed oil field might look like this one in<br />

Prudhoe Bay, Alaska.<br />

The process of drilling for oil<br />

Oil, like other fossil fuels, comes from decayed and pressurized plant material that has been buried and partially<br />

fossilized. Deep beneath the surface and permafrost, oil moves through rocks with microscopic holes (porous rock)<br />

until it comes in contact with nonporous rock. It collects at the contact of these two types of rock. The first step in<br />

drilling for oil is determining if a location has the kinds of rocks that are associated with oil deposits. Scientists can<br />

tell about buried rock by drilling cores of the rock or by tracing sound waves as they travel through different rock<br />

types (seismic surveying). Next, oil wells are built, tapping into the deposit. The high pressures underground force<br />

the oil up the well, where it can be collected. A pipeline transports this crude oil to a refinery. Here the crude oil is<br />

refined to oil that can be used to generate electricity or lubricate machines. In the arctic, oil development in isolated<br />

areas involves building roads, drilling platforms, pipelines, refineries, and housing facilities for workers.<br />

Courtesy of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service<br />

During seismic exploration activities in<br />

March 1985, vehicles compacted the snow<br />

and damaged underlying plants.<br />

Courtesy of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service<br />

Fifteen years later, scars from the<br />

seismic exploration activities can<br />

still be seen.<br />

file:///Ecoscenario/arctic/content.html<br />

Page 9 of 13

Ecoscenario: Arctic National Wildlife Refuge<br />

4/16/03 3:07 PM<br />

THE DEBATE<br />

Before making decisions that affect an ecosystem, it is important to gather information from a variety of sources.<br />

Below are the views of several individuals or groups that have an interest in the future of the Arctic National Wildlife<br />

Refuge. After each quote the hyperlink goes to the original source of the quote. Refer to these sites for more<br />

information.<br />

Use the information provided to decide where you stand on this debate.<br />

DEBATE: Should oil drilling be allowed in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge?<br />

People who support drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge<br />

Benjamin P. Nageak of the Inupiat people and former mayor of North Slope Borough, Alaska, on Arctic National<br />

Wildlife Refuge development<br />

"I fully understand the fears of many people that the presence of the oil industry on the coastal plains will disrupt<br />

the wildlife. They fear that industry activity will destroy a part of this earth that should be preserved.<br />

In 1969, when oil was first discovered on our lands, those fears were foremost in our minds as we fought for selfdetermination<br />

in order to be able to protect our resources. Since then, we have had over twenty years of working<br />

with the oil industry here. We enacted strict regulations to protect our land and the oil companies have consistently<br />

met the standards we imposed.<br />

"ANWR holds resources that can be extracted safely with care and concern for the entire ecosystem it<br />

encompasses. The Inupiat people, working through the North Slope Borough, will act in the same careful, caring<br />

and cautious manner we always have when dealing with our lands and the seas."<br />

http://www.anwr.org/people/nageak.html<br />

R. Dobie Langenkamp, National Energy-Environment Law and Policy Institute (NELPI), University of Tulsa,<br />

Oklahoma<br />

"30 years of experience in the existing North Slope oil fields, 80 miles west of ANWR, show no detrimental effects<br />

on caribou. In fact the Central Arctic caribou herd, which uses that area, has tripled in size since oil development<br />

began in the early 1970's."<br />

http://www.anwr.org/anwrtest/FP98/caribou.htm<br />

Mortimer B. Zuckerman, editor in chief, U.S. News & World Report<br />

"Here are some of the new developments: Directional or slant drilling makes it possible to drill numerous wells from<br />

a single small production pad, resulting in a footprint so small as to have virtually no impact on wildlife. Even if<br />

enormous reserves were discovered, only a fraction of the 1.5 million acres would be affected. There's more. During<br />

winter, when no caribou are present, ice roads, ice airstrips, and ice platforms would replace gravel, so that in<br />

spring, when the ice melts, the drilling during the harsh winter would have left virtually no footprint."<br />

http://www.anwr.org/features/conundrum.htm<br />

Lon Sonsalla, mayor, City of Kaktovik, Alaska, the only community located within the coastal plain of the Arctic<br />

National Wildlife Refuge<br />

"The most important thing is the future for the people out here. Declining revenues in the North Slope Borough have<br />

affected everybody who lives here. We're looking forward to the future and we are not sure what the future would be<br />

like without ANWR."<br />

http://www.anwr.org/features/whotocall.htm<br />

Survey results of residents of Kaktovik, Alaska<br />

78% of residents surveyed thought the coastal plain of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge should be open to oil and<br />

gas exploration.<br />

75% were satisfied with the environmental practices of the oil industry on the North Slope.<br />

71% felt the quality of life in Kaktovik will diminish if oil development ceases.<br />

http://www.kaktovik.com/anwr_survey.htm<br />

file:///Ecoscenario/arctic/content.html<br />

Page 10 of 13

Ecoscenario: Arctic National Wildlife Refuge<br />

4/16/03 3:07 PM<br />

Courtesy of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service<br />

This is one way the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge Area 1002 could be developed.<br />

People who oppose drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge<br />

Roger Kaye (wilderness specialist/pilot) and Jim Kurth (Arctic National Wildlife Refuge manager, 1995 to 2000), 6th<br />

World Wilderness Congress, Bangalore, India, October 1998<br />

"Lowell Sumner compared the Refuge to a national monument most Americans will never see. But by just knowing<br />

it is there, they have a tangible entity to which they can attach national values they hold dear and believe should be<br />

enduring. The Arctic Refuge serves a similar function for natural values...So we stand committed to the<br />

promise— the promise made by the past generation to all future generations—that this remnant landscape will be<br />

passed on undiminished, that its values will endure."<br />

http://alaska.fws.gov/nwr/arctic/indiacon.html<br />

Faith Gemmill of the Gwich'in Indian Nation<br />

" The birthplace of the Porcupine River Caribou Herd is considered Sacred. In 1988, when we heard of the proposed<br />

oil development, we gathered for the first time in over a hundred years in Arctic Village. Everyone spoke resolutely<br />

about how important the caribou are to our culture. At the end of the gathering, we spoke with one voice, one mind<br />

and one heart with a renewed commitment to protect our way of life for future generations."<br />

http://www.alaska.net/~gwichin/background.html<br />

Member of the Gwich'in community<br />

"The oil companies say there is over 27 billion barrels of oil under Area 1002, but only a small portion of that can<br />

actually be recovered."<br />

USGS report, Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, 1002 Area, Petroleum Assessment, 1998, Including Economic<br />

Analysis<br />

"Recoverable oil within the ANWR 1002 area is estimated to be between 4.3 and 11.8 billion barrels, with a mean<br />

value of 7.7 billion barrels."<br />

file:///Ecoscenario/arctic/content.html<br />

Page 11 of 13

Ecoscenario: Arctic National Wildlife Refuge<br />

4/16/03 3:07 PM<br />

http://geology.cr.usgs.gov/pub/fact-sheets/fs-0028-01/fs-0028-01.htm<br />

Norma Kassi, Gwich'in activist and Caribou Commons Project speaker<br />

"The relationship between the Gwich'in and the caribou is not one of convenience; it is one of necessity. A healthy<br />

Porcupine Caribou Herd is necessary for the continued survival of Gwich'in culture."<br />

http://www.cariboucommons.com/issue/issue.html<br />

Tanana Chiefs Conference, Inc., board of directors, Resolution No. 90-2, March 1990<br />

" Protect Porcupine Herd—Its Ecosystem and the Gwitch'in Way of Life<br />

"NOW THEREFORE BE IT RESOLVED: That the Tanana Chiefs Conference Board of Directors urges the U.S.<br />

Congress and President to recognize the rights of our Gwitch'in people to continue to live their way of life by<br />

prohibiting development in the calving and post-calving grounds of the Porcupine Caribou Herd; and<br />

"BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED: That the 1002 area of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge be made Wilderness to<br />

achieve this end."<br />

http://arcticcircle.uconn.edu/ANWR/tanana.html<br />

What has happened in this debate?<br />

In 1980 President Jimmy Carter signed the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act. This act expanded the<br />

refuge to its present size of 7,700,000 hectares (19 million acres). The Alaska Lands Acts left Area 1002 open for<br />

possible oil development upon the approval of Congress.<br />

The United States and Canada agreed in 1987 that they both have the responsibility of overseeing Porcupine<br />

Caribou Herd habitat within the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.<br />

A 1996 congressional study was conducted to assess the oil and gas potential of Area 1002. At that time it was<br />

concluded that the low price for oil did not make it profitable to open up the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge for<br />

drilling. The debate was reopened in 2001 after oil prices had risen and drilling in the refuge would be profitable.<br />

Government officials disagree about oil drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. They could decide either to<br />

make it a permanent reserve or to open it for drilling.<br />

The debate continues as Congress prepares to act on this issue. As the time draws near for Congress to act,<br />

supporters for both sides of the issue work to sway public opinion.<br />

Questions<br />

Which side of this debate do you support?<br />

What scientific evidence supports your position?<br />

After looking at the evidence, did you change your position? Please explain why.<br />

WEB LINKS<br />

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Official Arctic National Wildlife Refuge - http://www.r7.fws.gov/nwr/arctic/arctic.html<br />

Arctic National Wildlife Refuge - http://www.anwr.org/<br />

Arctic National Wildlife Refuge: A Special Report - http://arcticcircle.uconn.edu/ANWR/<br />

Benjamin P. Nageak of the Inupiat people and former mayor of North Slope Borough, Alaska, on Arctic National<br />

Wildlife development - http://www.anwr.org/people/nageak.html<br />

City of Kaktovik, Alaska, ANWR Survey - http://www.kaktovik.com/anwr_survey.htm<br />

file:///Ecoscenario/arctic/content.html<br />

Page 12 of 13

Ecoscenario: Arctic National Wildlife Refuge<br />

4/16/03 3:07 PM<br />

Congressional Research Service, CRS Issue Brief for Congress: The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, September<br />

1996 - http://cnie.org/NLE/CRSreports/Biodiversity/biodv-14.cfm<br />

Congressional Research Service, CRS Issue Brief for Congress: The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge: The Next<br />

Chapter, August 2001 - http://cnie.org/NLE/CRSreports/Natural/nrgen-23.cfm<br />

Faith Gemmill of the Gwich'in Indian Nation - http://www.alaska.net/~gwichin/background.html<br />

George N. Ahamaogk, North Slope Borough mayor - http://www.anwr.org/features/ahmaogak-speech.htm<br />

Gwich'in Steering Committee - http://www.alaska.net/~gwichin/index.html<br />

Lon Sonsalla, mayor, City of Kaktovik, Alaska - http://www.anwr.org/features/whotocall.htm<br />

Michael Grunwald, Washington Post staff writer, Some Facts Clear in the War of Spin over Arctic Refuge,<br />

Wednesday, March 6, 2002 - http://www.washingtonpost.com/ac2/wp-dyn/A44300-2002Mar5?language=printer<br />

Mortimer B. Zuckerman, editor in chief, U.S. News & World Report -<br />

http://www.anwr.org/features/conundrum.htm<br />

Norma Kassi, Gwich'in activist and Caribou Commons Project speaker - http://www.cariboucommons.com/issue/<br />

issue.html<br />

Northern Alaska Environmental Center, Alaska's Arctic -<br />

http://northern.org/artman/publish/arctic.shtml<br />

R. Dobie Langenkamp, National Energy-Environment Law and Policy Institute (NELPI), University of Tulsa,<br />

Oklahoma - http://www.anwr.org/anwrtest/FP98/caribou.htm<br />

Roger Kaye and Jim Kurth, The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge: The Evolving Meaning of a Symbolic Landscape -<br />

http://alaska.fws.gov/nwr/arctic/indiacon.html<br />

Taiga Net, Porcupine Caribou Herd - http://www.taiga.net/caribou/pch/<br />

Tanana Chiefs Conference, Inc., board of directors, Resolution No. 90-2, March 1990 - http://arcticcircle.uconn.edu/<br />

ANWR/tanana.html<br />

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, news release, Secretary Babbitt on USGS Assessment of Oil Reserves under<br />

Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, May 1998 - http://darwin.eeb.uconn.edu/Documents/fws-980517.html<br />

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, news release, Secretary of the Interior Bruce Babbitt on New Legislation by Senator<br />

Frank Murkowski to Permit Oil Exploration in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, March 2000 - http://news.fws.gov/<br />

NewsReleases/R9/A11C3D39-AC20-11D4-A179009027B6B5D3.html<br />

USGS report, Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, 1002 Area, Petroleum Assessment, 1998, Including Economic<br />

Analysis - http://geology.cr.usgs.gov/pub/fact-sheets/fs-0028-01/fs-0028-01.htm<br />

file:///Ecoscenario/arctic/content.html<br />

Page 13 of 13

Ecoscenario: Cimarron National Grasslands<br />

4/16/03 3:09 PM<br />

Cimarron National Grassland<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

Cimarron National Grassland is located in the southwest corner of Kansas. This grassland covers 44,500 hectacres<br />

(110,000 acres) in Morton and Stevens counties. The Cimarron River runs through the middle of Cimarron National<br />

Grassland. The Santa Fe Trail, an 1800s route from Missouri to Santa Fe, New Mexico, passes through the<br />

Cimarron National Grassland.<br />

Courtesy of U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service<br />

The Santa Fe Trail was an important<br />

trade route between Missouri and New<br />

Mexico.<br />

The southwestern portion of the vast grassland of the central United States and Canada is classified as a<br />

shortgrass prairie. It was home to huge herds of grazing bison. Native Americans of the Great Plains depended on<br />

the bison for survival. They were nomadic and followed and hunted the great herds. Pronghorn antelope and elk also<br />

grazed across the prairie. The shortgrass prairie also provides excellent habitat for black-tailed prairie dogs,<br />

lesser<br />

prairie chickens, and black-footed ferrets.<br />

file:///Ecoscenario/cimarron/content.html<br />

Page 1 of 12

Ecoscenario: Cimarron National Grasslands<br />

4/16/03 3:09 PM<br />

As settlers began moving west, the grassland was converted to grazing lands for cattle. Over 100 years ago, the<br />

land of Cimarron National Grassland was a cattle ranch known as Point of Rocks Ranch, operated by the Beaty<br />

brothers. This was the first permanent settlement in the area. Around 1885, homesteaders began to settle in this<br />

area as well. The rolling grassland was turned into a sea of wheat and other grains.<br />

Years of cattle grazing and farming, followed by a drought, degraded the soils and made them unproductive. By the<br />

1930s many acres were barren. The strong winds that blow across the prairie swept up the loose soil, creating huge<br />

dust and sand storms. This area was part of the Dust Bowl, an area that covered parts of Kansas, Oklahoma, and<br />

Texas, named for the great dust storms. Morton County, where part of Cimarron National Grassland is, was one of<br />

the most devastated areas.<br />

Courtesy of U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service<br />

Green area northwest of Elkhart, Kansas, is land in the Cimarron<br />

National Grassland.<br />

The U.S. government wanted to stabilize the soil so the land could be used again for agriculture. Healthy<br />

grasslands reduce soil erosion and water runoff and provide a dependable supply of summer forage for livestock and<br />

wildlife. The U.S. Congress approved the Bankhead-Jones Farm Tenant Act in 1937, allowing the government to buy<br />

some of this unproductive land with loose soil. The land was first administered by the U.S. Soil Conservation<br />

Service and in 1954 was turned over to the U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service. The former Point of<br />

Rocks Ranch became Cimarron National Grassland in 1960. It is the largest tract of public land in Kansas.<br />

Cimarron National Grassland is now a mixed-grass and shortgrass prairie. Riparian plant communities occur along<br />

the Cimarron River. Pronghorn antelope, bison, white-tailed deer, and cattle graze the land. This section of Kansas<br />

is at the heart of a major bird migration route. The surrounding land is primiarly agricultural, so Cimarron National<br />

Grassland serves as an important wintering island for birds.<br />

ABIOTIC DATA<br />

The climate of Cimarron National Grassland is semiarid, with warm summers and cold, dry winters. Winds blow<br />

across the grasslands, which makes the soil even drier. The growing and grazing season in this ecosystem is<br />

between April and September.<br />

file:///Ecoscenario/cimarron/content.html<br />

Page 2 of 12

Ecoscenario: Cimarron National Grasslands<br />

4/16/03 3:09 PM<br />

Cimarron National Grassland receives only around 25 centimeters (10 inches) of precipitation annually. Winds blow<br />

across the prairie at speeds up to 24 kilometers per hour (15 miles per hour). Moving air increases the rate of<br />

evaporation, causing plants to use water more quickly.<br />

About one-third of the annual rainfall occurs in the summer months of July and August.<br />

More precipitation falls during the summer than winter. Summer temperatures average 25°C (77°F); winter<br />

temperatures average 3°C (37°F). Precipitation can fall as rain or snow.<br />

file:///Ecoscenario/cimarron/content.html<br />

Page 3 of 12

Ecoscenario: Cimarron National Grasslands<br />

4/16/03 3:09 PM<br />

Hot summers and cold winters are typical for Cimarron National Grassland.<br />

Grass fires are an essential part of grassland ecosystems. Fire quickly breaks down organic material and returns<br />

minerals to the soil. Fires start naturally from lightning strikes. They quickly burn through dead grass and forbs and<br />

are spread by high prairie winds. Native Americans understood the importance of grass fires and often set them.<br />

They used them to clear lands and drive bison herds to areas where they were easier to kill. Until homesteaders<br />

actively fought the fires to protect buildings and crops, grass fires annually swept across the prairie.<br />

BIOTIC DATA<br />

Cimarron National Grassland is a shortgrass prairie grassland. The landscape is dominated by wide expanses of<br />

grass-covered prairie. Some of the dominant grasses are blue grama, side-oats grama, and buffalo grass. Side-oats<br />

grama is the tallest, growing 0.3–1 meters (1–3.5 feet) tall. It makes excellent nesting material for birds and small<br />

rodents and the seeds and leaves are good forage. Blue grama is a little bit shorter, growing 0.3–0.6 meters (1–2<br />

feet) tall. It is also good forage and nesting material. Buffalo grass is shortest, only 10–30 centimeters (4–12<br />

inches) tall. It spreads across the ground with creeping runners called stolons. While buffalo grass is a poor forage<br />

and nesting material for birds and small mammals, it is important food for pronghorn antelope, bison, cattle, and<br />

other grazing animals. The root systems of prairie grasses grow deeply into the soil. The deep roots survive fires<br />

that destroy the exposed top.<br />

Other range plants found growing among the grass at Cimarron are western ragweed, common sunflower,<br />

prickly<br />

pear cactus, sagebrush, and western buckwheat. A few trees dot the landscape, such as the cottonwood tree,<br />

Osage orange, and eastern red cedar. Trees are usually found growing along stream banks, near water wells, or<br />

near ponds. Most sapling trees in the open grassland burn before they can grow large enough to withstand a grass<br />

fire.<br />

file:///Ecoscenario/cimarron/content.html<br />

Page 4 of 12

Ecoscenario: Cimarron National Grasslands<br />

4/16/03 3:09 PM<br />

Some of the birds found at Cimarron are western meadowlark, horned lark, ferruginous hawk, golden eagle, and the<br />

lesser prairie chicken. The larks and lesser prairie chickens depend on the seeds produced by the grasses and<br />

other range plants. Prairie chickens were once extremely abundant in Cimarron, but their numbers have declined<br />

since the 1800s. Their decline is primarily the result of habitat loss, as land was cleared for agriculture. The use of<br />

herbicides and increased periods of drought have further reduced their habitat.<br />

Prairie dog towns were once common on the shortgrass prairie. Black-tailed prairie dogs live in a network of<br />

underground tunnels and chambers. Multiple entrances help ventilate the town and provide escape routes from<br />

predators and grass fires. A large prairie dog town may cover thousands of acres. In the late 1800s it is estimated<br />

that 280 million hectares (700 million acres) of the Great Plains was covered by prairie dog towns. Today 90–95%<br />

have been lost to agriculture or human development. There are only about 610,000 hectares (1.5 million acres) of<br />

prairie dog towns today. Their burrows are also home to black-footed ferrets, whose primary food source is prairie<br />

dogs. As the prairie dog towns declined, so did the populations of ferrets.<br />

Ranchers see prairie dogs as pests. Prairie dog towns make rangeland unusable by cattle. Few plants grow in<br />

prairie dog towns, and the ground is filled with holes that cattle may step in and injure themselves. Ranchers and<br />

recreational hunters often kill prairie dogs. When traps or baits are used, these also kill the black-footed ferrets. The<br />

reduced numbers of prairie dogs in a town means that there is less food for the ferrets.<br />

Courtesy of Nebraska Game and Wildlife Commission<br />

Black-footed ferrets once lived<br />

throughout the Great Plains.<br />

Black-footed ferrets are a rare sight.<br />

Courtesy of LuRay Parker, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service<br />

The black-footed ferret is the rarest mammal in North America. The Endangered Species Act protects endangered<br />

file:///Ecoscenario/cimarron/content.html<br />

Page 5 of 12

Ecoscenario: Cimarron National Grasslands<br />

4/16/03 3:09 PM<br />

animals like the black-footed ferret by outlawing hunting of the animals and conserving important habitat.<br />

Black-footed ferrets are making a slow comeback through captive breeding programs.<br />

The black-footed ferret was thought to be extinct in the wild until a population was discovered in Wyoming in 1981.<br />

Today, captive breeding programs at zoos around the United States are helping the ferret make a comeback. In<br />

1991, some black-footed ferrets were released into the wild in Wyoming, Montana, and South Dakota. Small<br />

populations of ferrets, about 220 animals, can be found in these states.<br />

The shortgrass praire is also home to plains pocket gophers. They live underground, but not in elaborate tunnels<br />

like prairie dogs. Pocket gophers have fur-lined cheek pouches where they carry grass seeds they collect. Prairie<br />

rattlesnakes, active year round, may search all these burrows and tunnels for food.<br />

The swift fox and black-tailed jackrabbit are small mammals found in Cimarron National Grassland. The swift fox,<br />

sometimes called a kit fox, is an omnivore. It can run 40 kilometers per hour (25 miles per hour) over small<br />

distances. The black-tailed jackrabbit is actually a hare. It lives in social groups of 25–30 and is active at night.<br />

Jackrabbits do not live in burrows. Both the swift fox and jackrabbit rely on speed and quick direction changes to<br />

escape predators.<br />

file:///Ecoscenario/cimarron/content.html<br />

Page 6 of 12

Ecoscenario: Cimarron National Grasslands<br />

4/16/03 3:09 PM<br />

Courtesy of Doug Canfield,<br />

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service<br />

Courtesy of Jack Dykinga, U.S. Department of Agriculture<br />

Art Explosion<br />

Black-tailed prairie dog Pronghorn antelope American bison<br />

The American bison, the largest land animal in North America, has roamed the prairie since prehistoric times.It has<br />

been estimated that 30–200 million bison roamed the Great Plains in the 1700s and 1800s. With the westward<br />

expansion, bison were slaughtered for meat and hides. By 1885 there were only 500 bison left. They were at the<br />

brink of extinction, but in protected areas like Cimarron National Grassland they have recovered. There are now<br />

more than 65,000 bison.<br />

The grassland is also home to elk and pronghorn antelope. Pronghorns are extremely fast runners, able to maintain<br />

speeds of 110 kilometers per hour (70 miles per hour) for up to 4 minutes. A more usual cruising speed for them is<br />

50 kilometers per hour (30 miles per hour).<br />

ISSUES<br />

One issue in Cimarron National Grassland is how to deal with rangeland fires. Some people view fire as beneficial to<br />

the ecosystem, and believe it is a tool for management. Others feel fire is dangerous, and should be put out<br />

quickly.<br />

Fire ecosystems like Cimarron National Grassland<br />

Many ecosystems are adapted to fire. Natural fires caused by lightning help shape the grassland landscape. Fires<br />

move across the prairie quickly, burning dead grass, but not getting hot enough to damage the root system. Sapling<br />

trees trying to get a foothold in the grassland are destroyed in grass fires. Few animals are lost, as most can flee<br />

the fires. Grass quickly grows back, and animals return to a renewed, lush grassland.<br />

Fires affect animals in various ways. Most are able to outrun the fires, but a few slower animals may have trouble<br />

escaping a fast-moving fire. Fire also destroys the cover small mammals use to hide from predators. Animals that<br />

can fly or run from the immediate danger of the fire may benefit. Once the animals disperse from the burned area,<br />

their numbers are less concentrated. Disease cannot spread as easily, so there are fewer deaths due to illness.<br />

Burrowing animals, like prairie dogs and pocket gophers, or species that live near water, like amphibians, may be<br />

unaffected by fire.<br />

Many species of birds, such as the bobolink, western meadowlark, and grasshopper sparrow, thrive in the open<br />

grassland meadows with no woody vegetation. They avoid areas that have been recently burned, but return when<br />

grasses regrow.<br />

file:///Ecoscenario/cimarron/content.html<br />

Page 7 of 12

Ecoscenario: Cimarron National Grasslands<br />

4/16/03 3:09 PM<br />

Courtesy of University of Nebraska Cooperative Extension<br />

Fires are now set in grasslands as part of<br />

management practices.<br />

Courtesy of University of Nebraska Cooperative Extension<br />

Prescribed grass fires are closely monitored to<br />

prevent uncontrolled burning.<br />

Fire policy<br />

Historically, the western United States was covered with huge areas of grassland. Native Americans used fire to<br />

stimulate grass growth and to herd bison. Early settlers used fire to clear land for agriculture. But after lands were<br />

cleared, fires were suppressed to protect crops and structures. Fire destroyed food sources and habitat for animals,<br />

which the public thought would be bad for the ecosystem. In 1935, the U.S. Forest Service set a goal of making<br />

sure all fires were out by 10 a.m. the following day. This disruption to the natural recycling of nutrients may have<br />

been one of the contributors to the depletion of the soil in the 1930s Dust Bowl.<br />

The suppression of fire also allows dead grasses and debris to build up. Woody trees and shrubs start to invade<br />

grasslands. This sets the stage for larger and hotter fires. Hot, intense fires destroy root systems and sterilize the<br />

soil. It may take many years for grasses to regrow and wildlife to return following an intensely hot fire.<br />

As the importance of fire was better understood, a policy called "back to nature" or "let it burn" was adopted by the<br />

U.S. Forest Service and the National Park Service. In this policy, forest and grassland fires were permitted to burn<br />

themselves out. Many Americans criticized this policy after one-third of Yellowstone National Park burned 1988.<br />

The park was allowed to burn for 4 months. The only firefighting efforts were to protect buildings and structures in<br />

the park.<br />

Better understanding of the grassland ecosystem has taught the U.S. Forest Service the importance of fire.<br />

Prescribed burning, planned and controlled, has increased over the last 40 years. This means that park managers<br />

set small, controllable fires. These fires reduce the buildup of fire fuel like dead plants. With this fuel gone, larger<br />

fires cannot spread as easily, and burn out more quickly. Prescribed burns can also help control non-native plant<br />

species and return vital nutrients to the soil.<br />

The fires that occur in Cimarron National Grassland are called stand-replacement fires. The fire kills only the aboveground<br />

parts of the plants. Introduced plant species with shallow root systems, not adapted to grasslands, are<br />

destroyed. These controlled fires also keep down the growth of woody plants. Without fires, trees and shrubs would<br />

slowly begin to appear on the prairie, and slowly convert it to woodland.<br />

In 2000, many wildfires burned out of control across the United States. These fires destroyed over 2.5 million<br />

hectares (6.3 million acres), mostly in Idaho and Montana. While it may seem that there are more wildfires burning<br />

in the United States than ever before, there are actually many fewer than in 1850. Overgrazing and fire suppression<br />

have led to dense thickets of trees and shrubs in some areas, which differ from the open forests and grasslands<br />

found before 1900.<br />

file:///Ecoscenario/cimarron/content.html<br />

Page 8 of 12

Ecoscenario: Cimarron National Grasslands<br />

4/16/03 3:09 PM<br />

Art Explosion<br />

Art Explosion<br />

Many ecosystems are adapted to fire.<br />

Fires move quickly across an open grassland. The fire<br />

does not get hot enough to destroy roots of native<br />

grasses.<br />

One of the keys to restoring an area like Cimarron National Grassland is returning the area to its natural cycle of<br />

burning. The National Forest Service plans burns well in advance. Prescribed fires in spring 2001 ranged from 2 to<br />

200 hectares (5 to 500 acres), and covered a total of 884 hectares (2185 acres). The most common size was an<br />

area of 130 hectares (320 acres).<br />

All fires in Cimarron National Grassland are regulated. Visitors cannot build open fires. To cook food or to stay<br />

warm, park visitors must use charcoal fires or gas stoves.<br />

Courtesy of George Vanover, U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service<br />

A prescribed burn is carefully set to reduce the amount of<br />

fuel in an ecosystem.<br />

THE DEBATE<br />

Before making decisions that affect an ecosystem, it is important to gather information from a variety of sources.<br />

Below are the views of several individuals or groups that have an interest in the future of the Cimarron National<br />

Grassland. After each quote the hyperlink goes to the original source of the quote. Refer to these sites for more<br />

information.<br />

Use the information provided to decide where you stand on this debate.<br />

file:///Ecoscenario/cimarron/content.html<br />

Page 9 of 12

Ecoscenario: Cimarron National Grasslands<br />

4/16/03 3:09 PM<br />

DEBATE: Should fires be permitted to burn in natural areas like Cimarron National Grassland?<br />

People who support using prescribed fires to improve grassland<br />

Ross W. Gorte, specialist in natural resources policy, Environment and Natural Resources Policy Division, CRS<br />

Report for Congress, Forest Fires and Forest Health<br />

"Following the Yellowstone fires in 1988, however, the use of prescribed natural fire was halted. While one can<br />

question whether the prescriptions were sufficiently responsive to burning conditions (fuel moisture, precipitation,<br />

dry lightning, winds, etc.), the termination of prescribed natural fire policies may have been an overreaction to the<br />

public sentiment."<br />

http://www.cnie.org/nle/crsreports/forests/for-23.cfm<br />

U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Fire and Aviation Management<br />

"Fire has helped shape North America's wild areas for thousands of years—its presence is essential for the survival<br />

of many plants and animals. We've learned that the lack of periodic fire in many wild areas increases risks to<br />

society and the environment. Much of the danger of destructive fire can be reduced through the increased<br />

application of prescribed fire and the planned use of wildland fire."<br />

http://www.fs.fed.us/fire/fireuse/rxfire/ecology/index.html<br />

George Wuerthner, Smokey the Bear's Legacy on the West<br />

"No single human modification of the environment has had more pervasive and widespread negative consequences<br />

for the ecological integrity of North America than the suppression of fire. Fire suppression has destroyed the natural<br />

balance of the land more than overgrazing, logging, or the elimination of predators."<br />

http://www.fire-ecology.org/research/smokey_bear_legacy.htm<br />

U.S. Geological Survey Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center, Effects of Fire in the Northern Great Plains:<br />

Effects of Fire on Upland Grasses and Forbs<br />

"One of the simplest and least expensive practices to improve poor quality grassland is prescribed burning."<br />

http://www.npwrc.usgs.gov/resource/2000/FIRE/GRASFORB.HTM<br />

Douglas H. Johnson, U.S. Geological Survey Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center: Effects of Fire on Bird<br />

Populations in Mixed-Grass Prairie: A Proposed Conservation Strategy<br />

"Results presented here suggest a conservation strategy for the northern Great Plains involving prescribed burning.<br />

On large areas, such as wildlife refuges, only portions should be burned in any particular year, and these on a<br />

rotational basis. The same prescription would apply to smaller areas that can be considered as components in a<br />

landscape, such as waterfowl production areas. They should be burned periodically, but not all in the same year.<br />

That strategy will assure that in any given year habitats in a variety of successional stages will be available for a<br />

variety of breeding bird species.<br />

"Although true grassland birds suffer short-term habitat losses from a burn, they do require grassland, which in turn<br />

requires periodic fire for maintenance. Several of these species have suffered long-term population declines.<br />

Moreover, they typically do not attain high densities or reproduce successfully in habitats other than grassland, as<br />

do birds in the other two categories. Furthermore, these species generally have breeding distributions centered in<br />

the grasslands of the midcontinent."<br />

http://www.npwrc.usgs.gov/resource/1999/firebird/conserve.htm<br />

U.S. Forest Service ranger<br />

"Many plants are adapted to fire. Some plants have seeds that can only germinate after a fire, either because they<br />

need to be heated or because there is something in the smoke the triggers that response. Fires also kill shrubs and<br />

small trees that start to appear in grasslands in the absence of fire."<br />

U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Historic Fire Regimes<br />

http://www.fs.fed.us/r4/curlew/Caribou_main/Caribou/forest_plan/Deis/Chapter3/fire_management/<br />

chapter_3_fire_historic_fire_regimes.htm<br />

People who are opposed to using prescribed fires in grasslands<br />

Resident near a proposed burn area<br />

"Look at what happened near Lewiston, California, on July 2, 1999. Even when fire personnel are there to watch the<br />

file:///Ecoscenario/cimarron/content.html<br />

Page 10 of 12

Ecoscenario: Cimarron National Grasslands<br />

4/16/03 3:09 PM<br />

fire, it can get out of control. I can't afford to lose my wheat fields or my home to an out-of-control fire."<br />

Bureau of Land Management report, Procedures Not Followed in Escaped Prescribed Fire, BLM Investigative Team<br />

Concludes, July 26, 1999<br />

"The Lowden Ranch prescribed fire jumped over control lines and burned about 2,000 acres before being controlled<br />

five days after it started. It destroyed 23 residences, as well as other structures."<br />

http://www.fire.blm.gov/News/press.htm<br />

Christina Ward, staff writer, DisasterRelief.org<br />

"New Mexico's 'Cerro Grande' fire, as it was called, may have been one of the most controversial, sparking<br />

widespread debate about U.S. fire management policy.<br />

"The Cerro Grande fire began as a prescribed burn in Bandelier National Monument, set by the National Park<br />

Service on May 4, 2000. It was intended to clear away dry underbrush that might ignite a more dangerous blaze<br />

later in the season. The plan backfired.<br />

"More than 43,000 acres burned, and 25,000 people were forced to evacuate. The fire destroyed or damaged 115<br />

buildings at the Los Alamos National Laboratory, birthplace of the atomic bomb, and came very close to a building<br />

that contained radioactive tritium."<br />

http://www.disasterrelief.org/Disasters/010509losalamosyear/<br />

National Jewish Medical and Research Center, Acrid Smoke from Raging Wildfires Hazardous to Those with Lung,<br />

Heart Diseases<br />

"The winds that fan the flames of summertime wildfires also can distribute large plumes of thick smoke miles from<br />

the actual fire, causing lung and heart problems for those with chronic health problems.<br />

'People closest to the fires are most at risk. That's why individuals living and working in communities near wildfires<br />

are often evacuated,' explains Lisa Maier, M.D., a physician in the Division of Environmental and Occupational<br />

Health Sciences at National Jewish Medical and Research Center."<br />

http://www.nationaljewish.org/news/healthtips/wildfires.html<br />

Homeowner near Cimarron National Grassland<br />

"We moved to the prairie to get away from city pollution. When the prairie is on fire, it is as bad as a smog alert day<br />

in the city."<br />

NASA Earth Observatory, First global carbon monoxide (air pollution) measurements, April 30, 2000<br />

"Carbon monoxide is a gaseous by-product from the burning of fossil fuels, in industry and automobiles, as well as<br />

burning of forests and grasslands."<br />

http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/Newsroom/NewImages/images_topic.php3?topic=atmosphere&img_id=4894<br />

Questions<br />

Which side of this debate do you support?<br />

What scientific evidence supports your position?<br />

After looking at the evidence, did you change your position? Please explain why.<br />

WEB LINKS<br />

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Cimarron National Grassland - http://www.fs.fed.us/r2/psicc/cim/<br />

Bureau of Land Management report, Procedures Not Followed In Escaped Prescribed Fire, BLM Investigative Team<br />

Concludes, July 26, 1999 - http://www.fire.blm.gov/News/press.htm<br />

Christina Ward, staff writer, DisasterRelief.org - http://www.disasterrelief.org/Disasters/010509losalamosyear/<br />

Congressional Research Service, CRS Report for Congress, Forest Fire Protection -<br />

www.cnie.org/nle/crsreports/<br />

file:///Ecoscenario/cimarron/content.html<br />

Page 11 of 12

Ecoscenario: Cimarron National Grasslands<br />

4/16/03 3:09 PM<br />

forests/for-34.pdf (PDF format)<br />

Douglas H. Johnson, U.S. Geological Survey Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center, Effects of Fire on Bird<br />

Populations in Mixed-Grass Prairie: A Proposed Conservation Strategy - http://www.npwrc.usgs.gov/resource/1999/<br />

firebird/conserve.htm<br />

Flora and Fauna of the Great Plains - http://www.gpnc.org/floraof.htm<br />

George Wuerthner, Smokey the Bear's Legacy on the West - http://www.fire-ecology.org/research/<br />

smokey_bear_legacy.htm<br />

Kansas Department of Wildlife and Parks - http://www.kdwp.state.ks.us/<br />

NASA Earth Observatory, first global carbon monoxide (air pollution) measurements, April 30, 2000 -http://<br />

earthobservatory.nasa.gov/Newsroom/NewImages/images_topic.php3?topic=atmosphere&img_id=4894<br />

National Interagency Fire Center - http://www.nifc.gov/index.html<br />

National Jewish Medical and Research Center, Acrid Smoke from Raging Wildfires Hazardous to Those with Lung,<br />

Heart Diseases - http://www.nationaljewish.org/news/healthtips/wildfires.html<br />

Nebraska Cooperative Extension EC 98-148-A, Grassland Management with Prescribed Fire - http://<br />

www.ianr.unl.edu/pubs/range/ec148.htm<br />

Prairie Parcel Restoration - http://www-ed.fnal.gov/help/prairie/Prairie_Res/care_main.html<br />

Ross W. Gorte, CRS Report for Congress, Forest Fires and Forest Health - http://www.cnie.org/nle/crsreports/<br />

forests/for-23.cfm<br />

Santa Fe National Historic Trails - http://www.nps.gov/safe/fnl-sft/webvc/vchome2.htm<br />

Santa Fe National Historic Trails, Point of Rocks, Cimarron National Grassland, Kansas - http://www.nps.gov/safe/<br />

fnl-sft/photos/kspages/ptroxks.htm<br />

U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Fire and Aviation Management - http://www.fs.fed.us/fire/fireuse/<br />

rxfire/ecology/index.html<br />

U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Fire and Aviation Management, News and Information - http://<br />

www.fs.fed.us/fire/news_info/<br />

U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Historic Fire Regimes - http://www.fs.fed.us/r4/curlew/<br />

Caribou_main/Caribou/forest_plan/Deis/Chapter3/fire_management/<br />

chapter_3_fire_historic_fire_regimes.htm<br />

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Mountain-Prairie Region, Black-Footed Ferret Recovery: At the Crossroads, April<br />

1995 - http://mountain-prairie.fws.gov/feature/ferrets.html<br />

U.S. Geological Survey Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center, Effects of Fire in the Northern Great Plains;<br />

Effects of Fire on Upland Grasses and Forbs - http://www.npwrc.usgs.gov/resource/2000/FIRE/GRASFORB.HTM<br />

file:///Ecoscenario/cimarron/content.html<br />

Page 12 of 12

Ecoscenario: Delaware Water Gap National Recrational Area<br />

4/16/03 3:11 PM<br />

Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

The Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area is a 64.3-kilometer (40-mile) stretch of the middle Delaware<br />

River, bordering the states of New Jersey and Pennsylvania. The Delaware River is the largest free-flowing river in<br />

the eastern United States, one of the few remaining in North America. There are no dams to block this river as it<br />

winds between mountain ridges and down river valleys to the ocean. The Delaware River is in the center of a<br />

watershed that covers 21,789 square kilometers (13,539 square miles) of Delaware, New York, New Jersey, and<br />

Pennsylvania. The Delaware River originates in the Catskill Mountains of New York and flows into Delaware Bay<br />

between Delaware and New Jersey.<br />

file:///Ecoscenario/delgap/content.html<br />

Page 1 of 14

Ecoscenario: Delaware Water Gap National Recrational Area<br />

4/16/03 3:11 PM<br />

Courtesy of National Park Service<br />

The Delaware Water Gap is known for the steep slopes and cliffs on either<br />

side of the river.<br />

The Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area has always attracted people with its beauty and natural<br />

resources. The earliest known inhabitants in this region, the Lenni-Lenape Indians, made their home here before the<br />

arrival of European settlers.<br />

In early colonial times Dutch settlers mined the mountains for copper. The mountain ridges were sites for forts<br />

during the French-Indian War, and remnants of Revolutionary and Civil War cemetaries can still be found. Forty<br />

kilometers (25 miles) of the 3476-kilometer (2160-mile) Appalachian Trail runs along the ridge tops in the Delaware<br />

Water Gap National Recreation Area. In the late 19th century, the area was a popular resort and vacation area for<br />

tourists from Philadelphia and New York City. Later, the area was used in silent movies, and became the home of<br />

numerous family and youth summer camps.<br />

The Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area borders 64 kilometers (40 miles) of the Delaware River, and<br />

covers 28,000 hectares (69,000 acres) in New Jersey and Pennsylvania. This park was established on September<br />

1, 1965, for public recreational activities, to preserve scenic and scientific resources, and to protect the area around<br />

the proposed Tocks Island Dam and Reservoir. In 1978, part of the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area<br />

was designated a National Wild and Scenic River. After years of planning and public opposition, plans for the<br />

controversial dam and reservoir were abandoned in 1992. The recreation area focuses on outdoor activities such as<br />

boating, fishing, canoeing, and swimming.<br />

file:///Ecoscenario/delgap/content.html<br />

Page 2 of 14

Ecoscenario: Delaware Water Gap National Recrational Area<br />

4/16/03 3:11 PM<br />

Courtesy of National Park Service<br />

The Delaware Water Gap National<br />

Recreational Area is a popular spot for<br />

water sports, such as fishing.<br />

The Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area is within a day's drive of 60 million people. In 1994, there were<br />

4.37 million visitors to the Delaware Water Gap, compared to 3.4 million in Yellowstone National Park that same<br />

year.<br />

Courtesy of National Park Service<br />

Trails through riparian forest line the riverbanks.<br />

Courtesy of National Park Service<br />

Small streams throughout the watershed feed into<br />

the Delaware River.<br />

The Delaware River is one of the cleanest rivers in the United States. The Delaware Water Gap National Recreation<br />

Area is an example of a freshwater ecosystem. This aquatic ecosystem is bordered by a riparian (river) forest buffer.<br />

A riparian forest buffer is a band of trees, shrubs, and native vegetation that borders a stream or river. The buffer<br />

zone protects the waterway by trapping and filtering pollutants as the groundwater flows through the subsurface.<br />

Together, the river and the buffer zone make up the freshwater ecosystem.<br />

file:///Ecoscenario/delgap/content.html<br />

Page 3 of 14

Ecoscenario: Delaware Water Gap National Recrational Area<br />

4/16/03 3:11 PM<br />

ABIOTIC DATA<br />

Summers at Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area are warm and humid, and winters are cold. Average<br />

summer air temperatures range between 17 and 23°C (62 and 73°F). Water temperatures are similar, but drop a few<br />

degrees as the water tumbles through ravines. Thunderstorms and dense fog are common in the summer.<br />

Sometimes large volumes of cold water flow down the river when excess water is released from Cannonsville<br />

Reservoir on the West Fork of the Delaware River in New York. This causes the water temperature in the Delaware<br />

River to drop.<br />

The Delaware Water Gap has cold winters. Air temperatures range between -2°C and 2.5°C (28 and 36.5°F). Water<br />

temperature drops to freezing, and most of the river is covered in ice each winter. Snow and ice storms are<br />

common.<br />

file:///Ecoscenario/delgap/content.html<br />

Page 4 of 14

Ecoscenario: Delaware Water Gap National Recrational Area<br />

4/16/03 3:11 PM<br />

Mountain elevations in the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area range between 150 and 430 meters (500<br />

and 1500 feet). Delaware River water depth is measured in Montague, New Jersey. Normally, the water is 1.5–2<br />

meters (5–6 feet) deep, but during floods the water can reach 7.5 meters (25 feet) deep. Floods occur because of<br />

stormy weather or because water has been released from an upstream reservoir, like the Cannonsville Reservoir in<br />

New York.<br />

The water in the Delaware Water Gap is generally smooth and quick-flowing. There are a few small rapids, but most<br />

of the river is a series of shallow riffles and quiet pools. The river substrate is pebbles and cobbles deposited by<br />

ancient glaciers.<br />

BIOTIC DATA<br />

The river, streams, and ponds of the Delaware Water Gap are bordered by a riparian forest dominated by eastern<br />

hemlock. The hemlock forest is intermingled with other species of tress, such as white pine, sugar maple, birch,<br />

and oak. This thick canopy of trees shades the water and helps produce the cool water temperatures and low light<br />

levels preferred by brook trout. The hemlock trees are also important bird breeding habitat, especially for the<br />

Blackburnian warbler, winter wren, and other songbirds. In June, flame azaleas burst into bloom and cover sunny<br />

hillsides. In summer, berry vines supplement the diet of black bears and raccoons.<br />

Along the banks of streams and calm pools, narrow-leaf cattails grow. They provide shelter and protection for many<br />

small animals. Near the water you might find amphibians like slimy salamanders and American toads. Amphibians<br />

breathe through their skin, which must stay moist for this gas exchange to occur. In the pond shallows, great blue<br />

herons hunt, and mallard ducks dabble. Northern water shrews dive from the stream's edge into the water to look for<br />

insects and small fish.<br />

Beavers haul logs from the surrounding forest to the water to build their lodges and dams. Common map turtles<br />

bask on the partially submerged logs of beaver dams and lodges. Some abandoned beaver lodges may be occupied<br />

by minks that forage along the riverbank.<br />

file:///Ecoscenario/delgap/content.html<br />

Page 5 of 14

Ecoscenario: Delaware Water Gap National Recrational Area<br />

4/16/03 3:11 PM<br />

Courtesy of the National Park Service<br />

Tree diversity in the hemlock forests at the Delaware<br />

Water Gap National Recreation Area.<br />

Courtesy of the National Park Service<br />

Plant diversity in the hemlock forests at the<br />

Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area.<br />

The surface of a summer pond might be covered in small insects, mayflies, each only 2.5 centimeters (1.0 inches)<br />

or less in length. Mayflies spend most of their lives as nymphs, clinging to underwater plants and eating algae and<br />

detritus. When they molt and emerge as adults, they live only a few hours or days. The mayflies floating on the<br />

water are the adults that have already mated and laid their eggs.<br />

A closer look at the water and at the rocks in it reveals a film of blue-green algae. These cyanobacteria are<br />

important producers in a freshwater ecosystem. Blue-green algae are very sensitive to changes in water nutrient<br />

levels. For instance, an increase in nitrogen can cause algae to grow rapidly. This is called an algal bloom. When<br />

the massive population of algae dies, the decomposition process can consume all the oxygen in the water. Such<br />

blooms decrease the amount of oxygen available to other organisms in the water.<br />

Howard Evans, Gillette Entomology Club at<br />

Colorado State University<br />

An adult mayfly rests on a plant stem.<br />

The rocks, vegetation, and mud of the stream bottom are covered with organisms. Tiny crustaceans called scuds,<br />

only 5–20 mm (0.2–0.8 inches) long, swim through the vegetation. Aquatic snails scrape algae off submerged plant<br />

stems and rocks. Freshwater mussels live in the muddy stream bottom, and get their food by siphoning water and<br />

file:///Ecoscenario/delgap/content.html<br />

Page 6 of 14

Ecoscenario: Delaware Water Gap National Recrational Area<br />

4/16/03 3:11 PM<br />

mud and filtering out plankton, algae, and detritus. In the early summer, tiny black tadpoles, larvae of the American<br />

toad, and other amphibians feed on plankton and algae. Wolf spiders lurk in the vegetation, waiting to capture<br />

another meal.<br />

Courtesy of National Park Service<br />

A bald eagle on the lookout for a fish dinner.<br />

Gerard Lacz, Animals Animals<br />

Brook trout are prey to bald eagles, bears, and<br />

humans.<br />

Farther out in the water, where it is deeper and cooler, brook trout lurk in the shade of the hemlock tree. They live in<br />

the gravely riverbeds where the water is clear and cool. The brook trout is a major predator of bottom-dwelling<br />

invertebrates and land-dwelling insects that fall into the water. Channel catfish live and feed along the muddy<br />

bottoms of ponds and rivers. Smallmouth bass swim in deeper water, and catch larger prey like frogs and smaller<br />

fish. These fish are eaten by still larger animals, like bald eagles and black bears.<br />

Freshwater ecosystems, like that at the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area, have intermediate<br />

levels of primary productivity, as compared to other ecosystems.<br />

Annual productivity, or the amount of energy provided by the producers in this ecosystem, is intermediate, about<br />

2400 kilocalories/square meter/year of blue-green algae and plant material. The productivity in this ecosystem<br />

changes with abiotic conditions such as temperature, depth, and water quality.<br />

file:///Ecoscenario/delgap/content.html<br />

Page 7 of 14

Ecoscenario: Delaware Water Gap National Recrational Area<br />

4/16/03 3:11 PM<br />

ISSUES<br />

Although today the Delaware River is one of the cleanest rivers in the United States, pollution from industry and<br />

urbanization has taken its toll on this river since the 1700s. Early settlements along the river dumped raw sewage<br />

directly into the water, and thousands of people died every year from waterborne diseases. As industrialization<br />

increased in the watershed, it became a polluted disaster area. By the 1940s,chemical factory wastes and<br />

untreated human sewage had fouled the river so badly that no fish could survive in its oxygen-depleted waters.<br />

Many efforts were undertaken to clean up the Delaware River, with little impact. In 1962, the Delaware River Basin<br />

Comission was created and combined the efforts of New York, New Jersey, Delaware, and Pennsylvania. In 1972,<br />

the Commission received $1 billion in federal grants under the Water Pollution Control Act, and the river began its<br />

dramatic comeback.<br />

While the efforts and results of the Delaware River cleanup are a victory for clean waterways, the issue has not<br />

gone away. New and unforeseen threats are arising for the Delaware River and many other rivers in North America.<br />

Courtesy of National Park Service<br />

Invertebrates are indicators of stream health because they are the first organisms to<br />

be affected by pollutants. Data on the number of invertebrate species, such as those<br />

shown above, can be used to locate problem spots early.<br />

While the water in the Delaware River is clean, the years of industrial pollution have left a legacy in the river bottom.<br />

Pollutants such as PCBs, mercury, lead, DDT, and other pesticides remain in river-bottom detritus. Invertebrates,<br />

such as scuds and zooplankton, feed on detritus and ingest the pollutants. These pollutants work up the food chain<br />

and are concentrated in fish and the fishes predators: bald eagles, black bears, and humans.<br />

Other threats to the river are ongoing. During storms, pollution from the land in the watershed is washed into the<br />

river. This includes herbicides and pesticides, fertilizers, and mine tailings. The most damaging is what is called<br />

point-source pollution. These direct discharges come from sewage treatment plants, factories, chemical and power<br />

plants, paper mills, and refineries. Increased regulations for industry and agriculture increase the cost for those<br />

goods and services to consumers.<br />

file:///Ecoscenario/delgap/content.html<br />

Page 8 of 14

Ecoscenario: Delaware Water Gap National Recrational Area<br />

4/16/03 3:11 PM<br />

The Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area is in a part of Pennsylvania that experiences acid precipitation.<br />

This "acid rain" affects all the watersheds in this part of Pennsylvania.<br />

Acid rain<br />

In the 1960s, people began to notice changes in normally productive lakes. Populations of fish and other aquatic<br />

organisms were declining. Trees that bordered lakes and streams were dying. This was happening not only in the<br />

United States and Canada, but also in Europe, Asia, and Australia. All of the affected areas were downwind from<br />

industrial centers.<br />

Courtesy of U.S. Environmental Protection Agency<br />

Rainwater, naturally acidic, has a pH between 5 and<br />

5.6. Acid rain, pH 4, is ten times more acidic than<br />

rainwater.<br />

Scientists suggested that pollution from factories and automobiles is poisoning the water in lakes and streams.<br />

Factory and automobile pollution frequently contains sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxide gases. These gases rise into<br />

the air, where they dissolve in droplets of atmospheric water to form sulfuric acid and nitric acid. When this acid<br />

falls with rain, snow, sleet, hail, or fog, it is called acid precipitation.<br />

file:///Ecoscenario/delgap/content.html<br />

Page 9 of 14

Ecoscenario: Delaware Water Gap National Recrational Area<br />

4/16/03 3:11 PM<br />

Why is acid rain such a problem?<br />

An acid is a chemical that in a water solution tastes sour and reacts easily with many other substances. Lemon<br />

juice, vinegar, and hydrochloric acid are acids. Lemon juice and vinegar are dilute acids, and hydrochloric acid is<br />

strong. Acidity is a measurement of how many charged hydrogen ions are in a solution. This is called pH, and it is<br />

measured on a scale of 1 to 14. Solutions with a pH between 1 and 6.9 are acidic, and those between 7.1 and 14<br />

are basic. Liquids with a pH of 7, like pure water, are neutral. There is a tenfold difference between each number on<br />

the scale. So a solution with a pH close to 2, like lemon juice, is ten times more acidic than a solution with a pH 3.<br />

Rainwater is naturally a little bit acidic, pH 5–5.6. Normally, rainwater picks up some minerals as it flows through<br />

the ground to lakes and streams. The pH of a lake or stream depends in part on what rocks and minerals are in the<br />

watershed and the river bottom. Some rocks, like limestone, are basic and neutralize acids. Most healthy lakes and<br />

streams have a pH between 7 and 9.2.<br />

Courtesy of National Atmospheric Deposition Program<br />

This map shows the pH of rain that fell in the United States in 1994.<br />

Acid precipitation, or acid rain, officially has a pH less than 5.6. However, the pH of acid rain can be as low as that<br />

of lemon juice or vinegar. Acid rain may fall directly into a lake or stream, or flow there as runoff from the watershed.<br />

If the lake contains limestone bedrock, the acid is neutralized for a while. However, eventually all the neutralizing<br />

capacity, or buffer, in the bedrock is used up, and the pH of the lake or stream begins to drop. When it receives<br />

acid precipitation, the pH of a lake can drop from 9.2 to below 4.5 in less than 10 years.<br />

file:///Ecoscenario/delgap/content.html<br />

Page 10 of 14

Ecoscenario: Delaware Water Gap National Recrational Area<br />