How the Great Depression Still Shapes the Way Americans Eat

From fortified foods to nutrition labels, the legacy of an early financial crisis lives on in kitchens across the United States.

It’s difficult to imagine that modern Americans, at the zenith of an era of self-styled gastronomy and rampant food waste, could have much in common with their Depression-era forebears who subsisted (barely) on utilitarian liver loaves and creamed lima beans. But trendy excess notwithstanding, the legacy of the 1929 financial crisis lives on: From the way that ingredients and produce wend their paths to American kitchens year-round, to the tone taken by public intellectuals and elected officials about food consumption and diet.

The nation’s hunger and habits during the Great Depression are of particular interest to Jane Ziegelman and Andrew Coe, whose book A Square Meal offers a culinary history of an era not known for culinary glamour. The pair not only trace what Americans ate—when they were fortunate enough to secure food—but also the divergent philosophies that guided government strategy in the battle against widespread hunger. One enduring, easily caricatured figure of the crisis is former President Herbert Hoover, a self-made tycoon who knew deprivation as an orphan in Iowa and whose rise to the White House was hastened by his heroic work to alleviate hunger in Europe following the First World War. “He was the great humanitarian,” Coe told me recently over breakfast. “He had the skills, he had the knowledge, he’d done it before. Everything was there.”

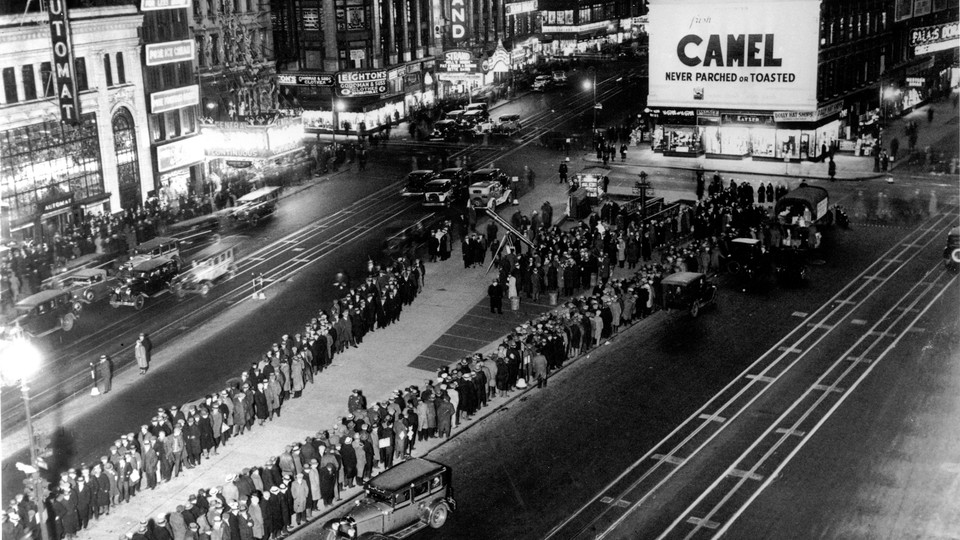

Hoover had come to power in the waning hours of the Roaring ’20s, which were reduced to a yawp on Black Tuesday, less than a year into his term. Though he had helped facilitate the feeding of much of post-war Europe, when faced with the prospect of growing hunger in the United States, Hoover staunchly opposed direct governmental relief in favor of of preserving the national credo of self-sufficiency. Hoover held fast to his optimism, hosting lavish White House dinners to project confidence and repeating the claim that “no one is actually starving.” But by 1931, the country’s slip was showing. Droughts and floods devastated American agriculture, unemployment was on its way to 25 percent, and breadlines in New York City were dispensing 85,000 meals a day. Hoover, who had won election in 1928 by one of the larger electoral margins in U.S. history, lost by an even more lopsided one to Franklin Roosevelt in 1932.

Despite establishing the U.S. welfare system, Roosevelt also expressed ambivalence about allocating government money for hunger relief. “[W]hile the immediate responsibility rests with local, public and private charity, in so far as these are inadequate the States must carry on the burden, and whenever the States themselves are unable adequately to do so the Federal Government owes the positive duty of stepping into the breach,” he said on the campaign trail, days before the election.

That intervention eventually took the form of the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA), a forerunner to the Works Progress Administration, which was founded in 1933. But even the assistance of FERA came with its share of difficulties and paternalism: In order to receive help, state and local governments were required to establish relief offices and to help fund them, all while facing invasive audits and routine inspections. And these material efforts were buttressed by government outreach to U.S. homemakers. Building on decades of groundwork, agents of the Bureau of Home Economics—a female-dominated branch of the USDA—were duly empowered (and funded) to insinuate themselves within communities to convince and instruct households on how to efficiently prepare adequately nutritious meals on tiny budgets. Millions tuned in to hear Aunt Sammy, the USDA-devised matronly companion to Uncle Sam, who offered recipes on the radio featuring foodstuffs being distributed by the government. “As FERA prepared to distribute five million pounds of beans,” Ziegelman and Coe write, “Aunt Sammy took to the airwaves briefing homemakers on legume nutrition.”

According to Ziegelman, the Great Depression set the division between 19th-century food culture and the beginning of modern food culture. “The government takes this very active role in deciding what Americans are going to eat and it’s the beginning of a sort of nutrition consciousness.” she says. “It’s when we begin to think about food groups in terms of food groups and vitamins and minerals and evaluating food on that basis. It’s the beginning of when we look at the sides of our cereal boxes and see how many grams of sugar and how much fiber and make our decisions based on those calculations.”

In that sense, it’s not hard to draw a parallel between government’s exhortations then and, First Lady Michelle Obama’s current initiatives to dot the national culinary landscape with a few more wholesome vistas. But while more recent efforts to change American dietary patterns have revolved around suggestions such as swapping potato chips with kale chips, the direness of the Depression reduced public campaigns about food to humbler aims—providing basic sustenance and battling vitamin deficiencies—which were austerely championed by Eleanor Roosevelt. “In home economics, Eleanor found a way of thinking about food that was consistent with her values,” write Ziegelman and Coe. “Built on self-denial, scientific cookery not only dismissed pleasure as nonessential but also treated it as an impediment to healthy eating.”

Accordingly, ethnic foods with their (supposedly) hunger-triggering spices were vilified and considered “stimulants” along the lines of caffeine and so, in their stead came prune puddings, canned-meat stews, and dairy-heavy vegetable casseroles featuring America’s first fortified foods. And, though diminished by decades of culinary evolution, there are still vestiges of this old way of eating at tables across America. “Some of the wacky creations—the Jell-O salads, the cans of celery soup mixed with tuna fish and mashed potatoes—that’s maybe not happening here [in New York], but I think that’s very much alive more toward the middle of the country,” Ziegelman explained. (Indeed, in this month’s Atlantic cover story, President Barack Obama tells Ta-Nehisi Coates about coming across the familiar sight of “the same Jell-O mold that my grandmother served” when he enters the homes of white farmers and trade unionists.)

Beyond the science-driven fare and nutritionism of the Depression diet, American foodways were also reshaped by government projects that slowly pushed the United States toward recovery. “Before the Depression, America was not very well connected by roads and rails,” Coe explains. The New Deal-mandated creation of infrastructure—which also included power lines and electricity—would pull rural farm areas into larger food systems and eventually help deliver refrigerators to the masses. While canning and pickling and seasonal, farm-to-table meals may have recently come crashing back into vogue in the United States, it was these labor-intensive methods from which many households were seeking reprieve. “Farmers could now sell their produce at the nearest regional center where it would be distributed all across the country and, at the same time, they could now get out-of-season foods, canned foods, frozen foods, or fresh oranges from Florida or California all around the year,” says Coe.

Though it may seem like boom times for haute eating, there are resemblances, both subtle and obvious, between modern-day America and its Depression-era analogue. As Ziegelman explains, parents are still trying to sneak vegetables into their children’s food while the reign of nutrition bars and protein shakes might appear to be the souped-up descendents of the technology-enabled, basic-by-design fare of the 1930s. More urgently, hunger has returned. “As of 2014, the most recent year on record, 14 percent of all American households are not food secure,” Ned Resnikoff noted in The Atlantic back in July‚ a three-point bump from pre-Great Recession levels. “That’s approximately 17.4 million homes across the United States, populated with more than 48 million hungry people.” The relative inexpensiveness of food in the United States, which has long softened the blow of stagnant wages, may fall out of reach once again. And given how proposed spending cuts could be meted out by President-elect Trump and his administration, those numbers of hungry Americans seem destined to go up.