Engadget has been testing and reviewing consumer tech since 2004. Our stories may include affiliate links; if you buy something through a link, we may earn a commission. Read more about how we evaluate products.

How HTC and Valve built the Vive

A VR headset four years in the making.

Long before the Vive was born, both software developer Valve and phone manufacturer HTC were separately looking into virtual reality.

In 2012, VR was beginning to creep back into the public imagination. It started in May of that year, when id Software's John Carmack demoed a modified Oculus Rift running Doom 3. The following month, he took the Rift to a wider audience at the E3 games convention. By August, Palmer Luckey launched the Oculus Kickstarter campaign, and it broke records. Almost overnight, the Rift went from an intriguing prototype to a truly exciting reality. But while all of this was happening, Valve was already at work on its own solution.

Valve, before HTC

Valve's early work on prototypes is fairly well documented. In 2012 it developed a system with a simple head-mounted display (HMD), a camera and some AprilTags to enable positional tracking. AprilTags are like larger, simpler QR codes and are commonly used for augmented reality, camera calibration and robotics (they're all over the place in Boston Dynamics' latest Atlas video). Valve wasn't being particularly secretive about this: While the Oculus Kickstarter campaign was grabbing headlines, the company was showing off its VR experiments to The New York Times.

A very early VR prototype (image credit: Stuart Isett / The New York Times).

After its tracking was up and running, there was another big problem to overcome: The images on the HMD still appeared blurry. As Valve experimented, the company realized that for gaming, a low-persistence display was a must. In this case, that meant lighting up a panel for one millisecond and then turning it off for nine milliseconds, in order to prevent ghosting. To prove its theory, it first created a "telescope" that let you look into another three-dimensional space; next it designed a custom board to output high-frame-rate, low-persistent images to off-the-shelf AMOLED displays.

These panels then went into a "big ugly headset" (Valve's Chet Faliszek's words, not mine), and testing continued. "We were looking for what we had hoped was out there, but didn't know if it existed," Faliszek said. The team at Valve fell in love with "room-scale" VR and the freedom of movement it brings. "We just worried about the commercial aspect, and the quality aspect. No one was going to wallpaper their room like that, and we didn't have an input solution that matched." Something else was required.

HTC, before Valve

In early 2013 HTC was a smartphone company, but it wanted to be more. "We knew that VR was very similar to the early days of smartphones," Daniel O'Brien, HTC's vice president of VR, explained. "This is a new medium, this is coming, we know it's coming. We need to get in on the forefront of it." That meant prototyping. Lots.

Claude Zellweger, the designer best known for his work on the One series of smartphones, was heading up these efforts. "I'd been tasked by [former CEO] Peter Chou to look at technologies that could take the company in a different direction secondary to the smartphone business and started the advanced concepts team."

The advanced concepts team was a small group that birthed both the periscope-like Re Camera and Re Grip wearable, but by far its biggest venture has been the Vive. Originally it was to be the Re Vive -- an apt title for a bold new product from a troubled smartphone company -- but the "Re" slowly drifted away from the company's marketing message. Peter Chou took over the team after stepping down as CEO and renamed it the HTC Future Development Lab.

HTC's Re Camera.

The team explored both augmented reality (think Microsoft HoloLens) and VR and decided to focus on the latter. But while Samsung seized the opportunity to pair an optical shell with its flagship phones, HTC quickly discounted the idea. "We thought about it from the ground up as a totally different product category that needs its own solutions," said Zellweger, who's now the company's Head of Design. "Out of the gate we never considered something that is glued together with a phone as a display." Instead, HTC approached the VR headset the same way it approaches phones: Get in early, and get in at the high end.

The culmination of this initial foray into virtual reality, Zellweger explained, "neatly coincided" with the meeting between Valve and HTC.

The Oculus rift

Valve's work up to 2013 had made real-time tracking in VR a viable proposition. But although it had worked out the fundamentals, it wasn't about to build its own headset. And why would it? The public had already voted with its wallet, funding Oculus to the tune of $2.4 million. In Jan. 2014 Valve announced that it would collaborate with Oculus on tracking to "drive PC VR forward." It also said it had no plans to release its own VR hardware, although it noted that "this could change" in the future.

It's clear that at some point Oculus and Valve's cooperative spirit fell apart. It could be that Oculus and Valve disagreed on what VR should be: The Rift and Vive certainly offer different experiences. But it's also been suggested that communication from Oculus ground to a halt in the months after the Facebook acquisition, which forced Valve to explore other paths. It's unlikely that anyone will go on the record to confirm that for years. All we know is that in early January, Luckey was reportedly calling Valve's tech "the best virtual reality demo in the world," and by late spring, HTC and Valve were meeting to hammer out a deal.

The exact details of that meeting aren't public. Zellweger paints it as a face-to-face between "Cher and Gabe," referring to HTC co-founder Cher Wang and Valve co-founder Gabe Newell. It obviously yielded positive results.

Together at last

As soon as the agreement was signed, work on the Developer Edition began. "The next week we went down to San Francisco [where Zellweger's design office is] to install a tag room down there," Faliszek recounted. "They had these designs going for what the headset would be like. It was so fast-moving." Zellweger recalls the rapid pace of those early days fondly. "We'd go off and iterate on a bunch of ideas. There was sort of a key moment where we presented our vision for the product to Valve, which at that point incorporated an early form of tracking ... everyone worked out it could be great."

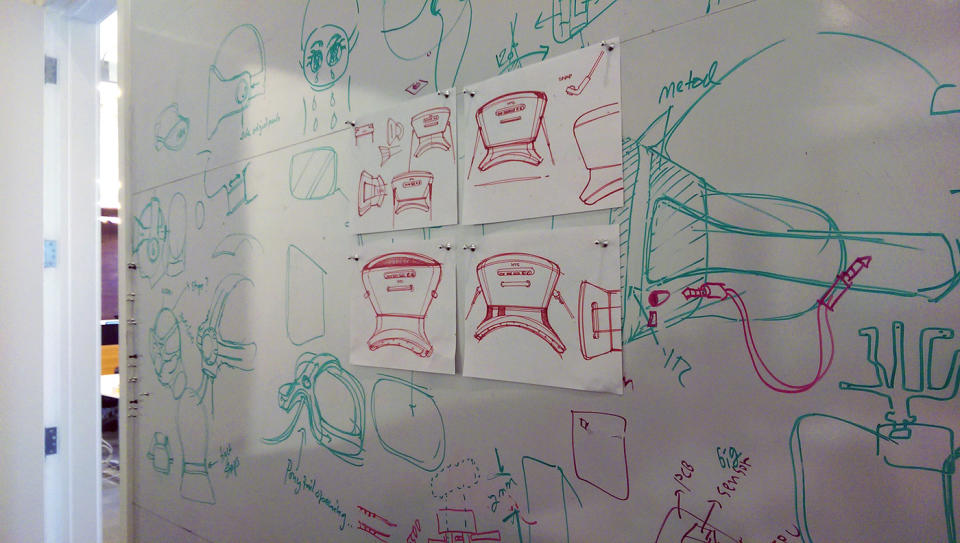

A whiteboard at HTC's design studio illustrates the company's prototyping process.

Although its public demonstrations were still rooted in the system developed in 2012, Valve had begun to move away from the impractical AprilTag-based system. A pair of alternate solutions emerged: dot tracking and laser tracking. Dot tracking works exactly as you'd imagine. Controllers and headsets are covered in dots, and a stationary camera uses machine vision to determine the position of those dots in real time. Then there's laser tracking, which puts sensors on the headset and controllers in place of dots and includes a discrete, laser-emitting base station.

Laser tracking offers the most accuracy, but to enable it at room scale puts severe constraints on the headset. To understand why, a quick science lesson is required. The base stations contain emitters that rotate rapidly to send a laser beam across the room and LEDs that flash 60 times each second. The headset has sensors to detect the invisible light show, and it determines its position and orientation based on the gaps in time between the laser and LEDs hitting each sensor. For that to work properly, you need a wide spread of sensors pointing in different directions.

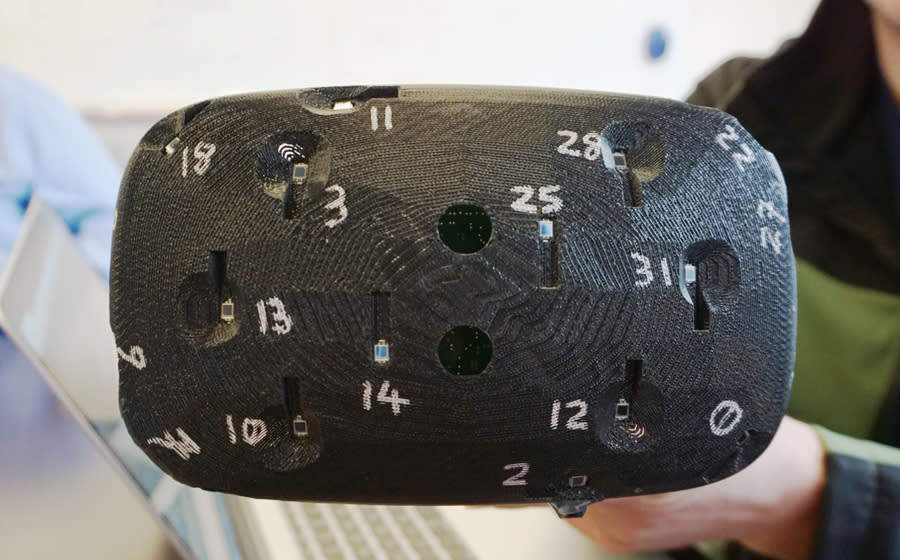

Knowing that laser tracking was a must, HTC approached the Developer Edition pragmatically. Valve knocked up a laser-tracking prototype. It worked, but it was rough and covered with exposed circuitry. Zellweger's team had to turn it into a product. Working off early sketches, they used 3D printing to determine where the sensors should be positioned, which then informed the rapidly evolving design. All through this process, prototypes were flying between Valve HQ, HTC's San Francisco office and its Taiwan-based engineering team.

"We had to make adjustments to the headset, but we couldn't make any compromises with tracking."

O'Brien explained that the "tracking had to be perfect, and we had to make adjustments to the headset, but we couldn't make any compromises with tracking." The function-over-form principle that Valve and HTC followed is perfectly illustrated by looking at the early-prototype headset pictured above. It's a 3D-printed model that exists only to test the positioning of the sensors. Although there's no real design to speak of, the shape of the headset is there.

The controller issue

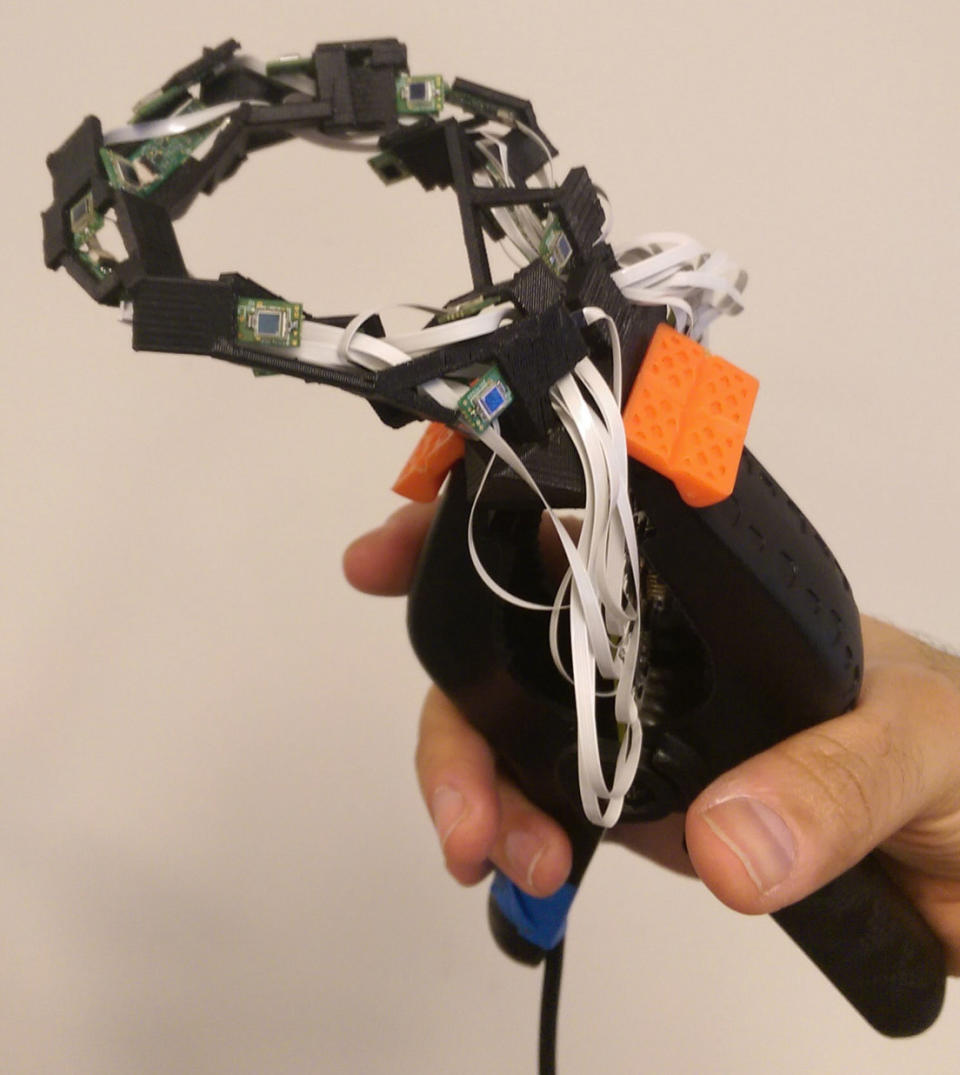

Two early attempts at a VR controller.

Valve's early work on VR controllers was primitive, to say the least. The first (that's been made public) simply attached what looked like an oversized Dungeons & Dragons die to the top of a Steam Controller. The original attempts at a laser-tracked system followed a similar path, grafting some antenna-like sensors onto a regular game controller. But the team swiftly realized they needed something different.

"This is the one time in our lives when we can make a clean start," explained Faliszek. "We said, 'You know what, we're not going to have X, A, B, Y. We're going to say no. We're going to make something specifically for the thing we're making it for.'" What Valve and HTC landed on was a mashup of two existing products. The Vive controllers have the same basic form of Sony's PlayStation Move, introduced in 2010, but add the precise input of the trackpad from Valve's Steam controller as well as laser-tracking sensors.

For a first-gen product, the controllers offer an elegant solution. But they weren't always so dainty. The initial prototype was a bunch of circuitry attached to a pair of spring clamps, which served as a test-bed for the laser-tracking system. It swiftly evolved into the controller first shown to the public, now referred to as the "sombrero" because of its solid tracking disc.

The sombrero doesn't have many buttons, which was apparently the source of a lot of initial complaints from developers. "The first thing they'd say is, 'There aren't enough buttons,'" Faliszek recalled. "By the second week they'd be like, 'Oh, I don't need all those buttons, in fact I'm probably not going to use all these.'" Many common tasks previously assigned a unique button are now being handled by gestures. Faliszek gave the examples of replacing the "press I for inventory" trope with simply reaching behind you for a backpack or eschewing the "lean" command by physically leaning to one side to look around an obstacle.

Developers

Less than six months after HTC and Valve started working together, they were ready to share their vision with others. On Oct. 20th, 2014, a select group of developers were invited to Valve's Bellevue, Washington, offices to try out Vive. "We made them sign NDAs [nondisclosure agreements] just to look at the actual NDA," Faliszek laughed. "It confused everybody, but they came." Who wouldn't?

Developers were adamant that HTC and Valve shouldn't "splinter" the community.

They gathered a lot of feedback from that initial meeting. Developers were adamant that HTC and Valve shouldn't splinter the community. No choice between 180-degree tracking and 360-degree tracking. No bundled controllers or unbundled controllers. One product. One specification. "We'd been thinking similarly along the way," Faliszek said. "It was really an affirmation of that."

The first developer kits rolled out in Dec. 2014. Known posthumously as the "-v1," they were handmade, hand-delivered and set up personally by Valve employees. In the following weeks, HTC's production line kicked in, and the first factory-made units started finding their way to more developers.

As a smartphone manufacturer, HTC knows more than a few things about products breaking cover early. But the Vive didn't. "Over 20 companies were involved, and no one leaked," O'Brien explained. Why? Faliszek attributes it to camaraderie among developers. There were only so many people with the kits, and Valve arranged a private forum where everybody could share their work and help one another out.

One strength of this community was that developers would apparently call one another out on their mistakes. "Normally when a developer shows another developer something they say, 'Hey that's great,' rather than, 'Hey no you're screwing up here, you have to fix this, this is wrong,' but that's what they were doing."

Going public

With developers on board, the aggressive pace of the Vive project continued. HTC and Valve decided on MWC 2015 for its grand reveal. A second showcase two weeks later at GDC 2015 focused on games. By every account, the launch was a complete success. Even journalists who had tried dozens of VR experiences before Vive were impressed by the room-scale demos and the accurate head and controller tracking. The plan was then set in stone. Exactly one year in, preorders were to go live, with the final consumer edition to be unveiled at MWC and game demos at GDC. Now they had to make the thing.

Engadget editor James Trew models the first Vive Developer Edition at MWC 2015.

What followed was exactly what had come before: iteration. That led to the Pre developer edition, which was made public in January and is almost identical to the consumer version. At first glance, not much has changed. But on closer look, almost nothing is the same. The final edition is considerably smaller and lighter than the original, and the strap has been completely redesigned. These modifications combine to push the center of gravity closer to the face, which is important, as it means the headset is more stable when you're moving around. The sensors have also been covered up, and the lens-adjustment and strap-tightness mechanisms have been refined. Finally, the cables on the original were thick and protrusive; now they're thinner and ... still pretty protrusive. They're less in your way when you move around, but you still know they're there.

Aside from comfort, two additional features have made their way to the headset over the past year: a front-facing camera and a microphone. The front-facing camera is part of Chaperone, a system announced in January that's meant to keep you safe and in touch with the real world. With the press of a button, the Vive can display real-world images on top of the virtual world you're inside. This was always part of the plan -- we were told as much back in January -- and O'Brien said the original developer kit nearly had a pair of cameras on the front (you can see the place where they were supposed to be added in our first hands-on), but "it didn't work, so we just introduced it at a later point when it did."

The consumer edition of the Vive, complete with controllers and base stations.

The same is true of the microphone, which you can use to answer calls while inside the headset. The Pre developer edition actually has a microphone inside. But because HTC hadn't worked out the software yet, it was omitted from the announcement and revealed alongside pricing in late February.

Aftercare

Faliszek, O'Brien and Zellweger all claim that developing the Vive was trouble-free. Given the tight time scale here -- less than two years since Valve and HTC first started working together -- it's clear it's been a pretty smooth ride. Headsets, controllers and base stations are flying off the factory line. All that's left now is to sell them.

The Vive launch commercial.

Assuming the Vive is a success (HTC doesn't break out sales numbers, but it's sold through its entire stock for April), how long until customers need to replace their headset with the "Vive 2"? A console might last eight years, a top-of-the-range gaming PC might stay relevant for five years, a smartphone just two. Neither HTC nor Valve want to divulge their future plans. But they do believe the Vive has legs.

The companies could have made a better VR headset -- there's no doubting that. The resolution on its two 1,200 x 1,080 panels (one for each eye) could have been increased, for one. But the bottleneck isn't the headset; it's the PC that's powering it. The GPU requirements are already high, calling for an AMD Radeon R9 290 or an NVIDIA GeForce GTX 970. These are cards that, even years after their release, still cost about the same as a PlayStation or Xbox. "The idea was to pick something that's super high-end so in a year there'll be enough people that have the graphics cards to run this," explained Faliszek.

A Vive 2 -- or whatever the sequel will be called -- has to happen. "At some point you're going to want to increase resolution," Faliszek admitted. "We'll definitely learn more. We'll find out what's interesting. But you can't [release a new headset] lightly." Once PC graphics cards are capable of pushing the required 90 frames per second to a higher-resolution panel, it's likely we'll see a new Vive. But that doesn't mean that early adopters will be left behind.

"We've made it very clear," O'Brien asserted. "Once the consumer edition is out, there'll be the Pre, the v1 developer kit, and the -v1s. We've designed a system that will be backwards compatible and we will definitely maintain that." Faliszek continued, "When we release this, these are living things. This hardware is going to keep updating, we're going to keep taking care of it. It's not like, release it and forget about it."