- Scientists have unearthed 28 previously undiscovered viruses, which were trapped in glacial ice from 15,000 years ago.

- The team collected the samples from the Guliya ice cap in Tibet, and published their work to the pre-print website, BioRxiv.

- As glacial ice and permafrost around the world continues to thaw, scientists are concerned that ancient pathogens and toxic chemicals may be released into the environment.

It's the stuff of a Stephen King novel.

Researchers from China and the U.S. embarked on a field trip to Tibet in 2015, and discovered 28 previously undiscovered virus groups—in a melting glacier. They recently detailed their findings in a paper posted to the non-peer reviewed pre-print website bioRxiv.

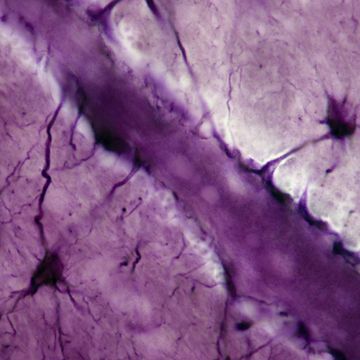

The researchers drilled a 164-foot hole into the glacier, gathered two ice core samples from the 15,000-year-old glacier, and then later identified them in a lab. In total, they identified 33 virus groups—28 of which were completely new to science.

From Tibet to the Arctic to Antarctica, glaciers and ice caps around the world are melting at alarming rates. Scientists are racing the clock and climate change to collect, identify, and catalogue the microbes found in ancient ice. Having a record of these bacteria, viruses, and fungi paints a sharper picture of our prehistoric past and could be valuable for use in studying future pathogens.

Meltwater from glaciers and ice caps could ferry harmful pathogens along streams, rivers, and other important waterways, potentially exposing humans to new microbes, the researchers report. But ice isn't the only thing that's melting. Thawing permafrost, a frozen layer of earth found in high latitudes and at elevation, creates its own unique set of challenges.

Gases like methane and carbon dioxide, which have been trapped in the long-frozen earth, are being released into the atmosphere at alarming rates. Permafrost houses twice as much carbon than what's currently found in the atmosphere, climate change scientist Sue Natali of the Woods Hole Research Center told the BBC.

In recent years, researchers have pulled samples of smallpox, Spanish flu, bubonic plague, and even anthrax from thawing permafrost. Scientists have also found harmful pollutants, such as mercury, trapped in the reservoirs beneath Alaskan permafrost.

And then there's the structural damages associated with the thawing permafrost. Swedish Nuclear Waste Management, a company that stores Sweden, Finland, and Canada's spent nuclear fuel atop permafrost, has joined other norther facilities to address future thawing. Any slumping or sagging could potentially jeopardize the structural integrity of the agency's nuclear waste containment system.

Countless other buildings and even Alaskan cemeteries (!) are in jeopardy of structural damage wrought by destabilized permafrost. In 2017, the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, a massive plant seed repository on the Norwegian island of Spitsbergen, flooded after the permafrost on which it was built began to sag.

While scientists have discovered a seemingly endless series of terrifying plagues, diseases, and chemicals in thawing permafrost and melting ice, there's a very, very thin silver lining. The great thaw has also revealed long-lost treasures from an earlier time.

In 2018, scientists discovered an ancient 18,000-year-old doggo (okay, it's probably a wolf) trapped in permafrost just outside of the Siberian capital, Yakutsk. It still had a lush, velvety coat. Researchers have also unearthed mammoths, more wolves, and arctic mummies.

Correction: We've updated the article to clarify that Tibet is not in the Arctic. We apologize for the confusion.

Jennifer Leman is a science journalist and senior features editor at Popular Mechanics, Runner's World, and Bicycling. A graduate of the Science Communication Program at UC Santa Cruz, her work has appeared in The Atlantic, Scientific American, Science News and Nature. Her favorite stories illuminate Earth's many wonders and hazards.