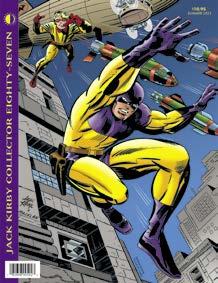

$10.95 SUMMER 2023

JACK

Sandman& Sandy COLLECTOR EIGHTY-SEVEN 1 8 2 6 5 8 0 0 5 0 2 3

TM & © DC Comics.

KIRBY

LAW & ORDER!

JACK FAQs 4

Mark Evanier’s 2022 Kirby Tribute Panel, featuring Frank Miller, Jeremy Kirby, Bruce Simon, Rand Hoppe, and Steve Saffel

COP OUT 17

Sgt. Muldoon: Villain or Hero?

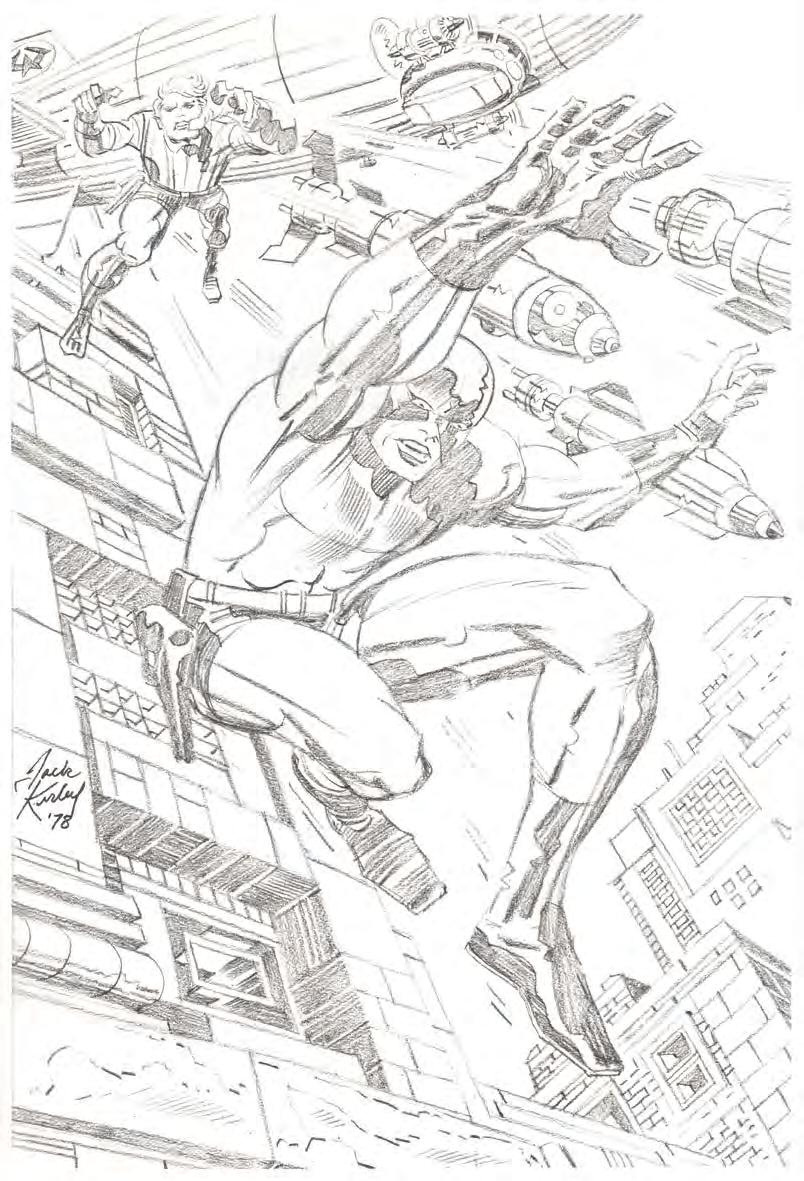

GALLERY 20 Kirby’s super cops

INCIDENTAL ICONOGRAPHY 28

Sean Kleefeld accuses Ronan of fluctuating design

HOT DOCS 30

Kirby’s days in and out of court

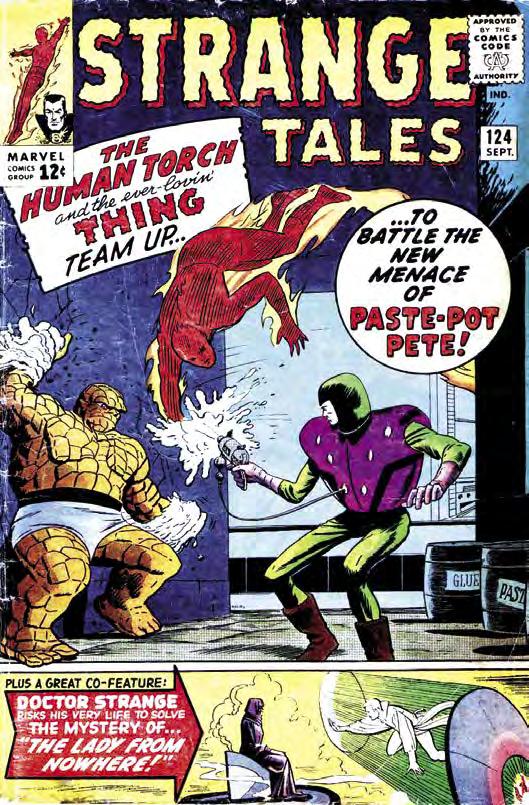

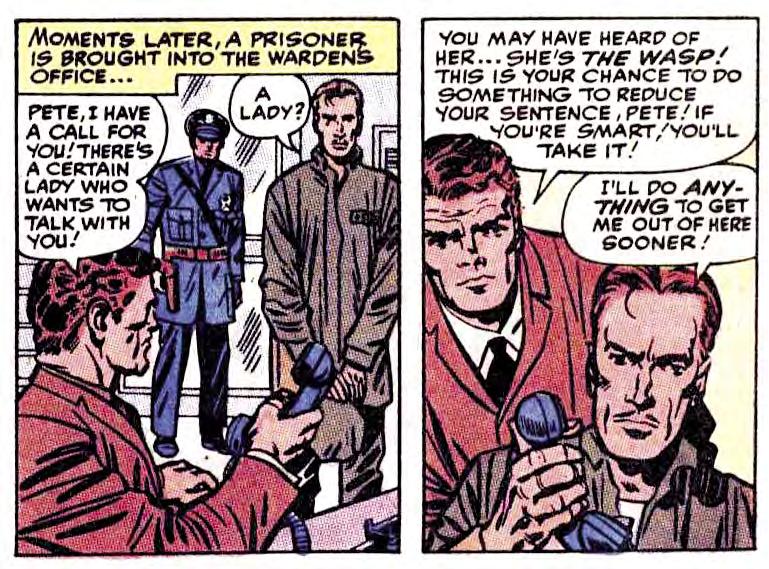

BAD MAN-AGEMENT 32 who redesigned Paste-Pot Pete?

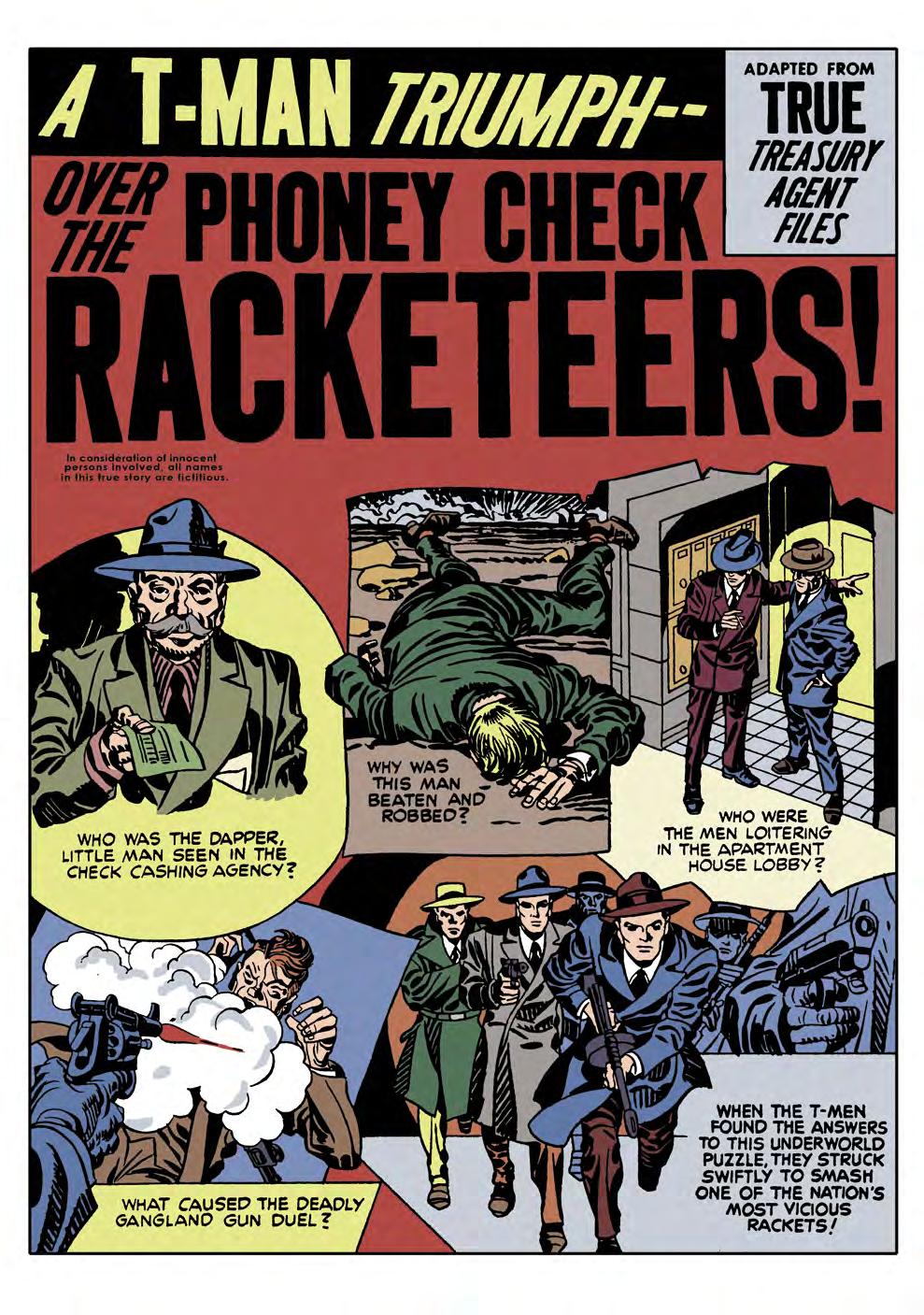

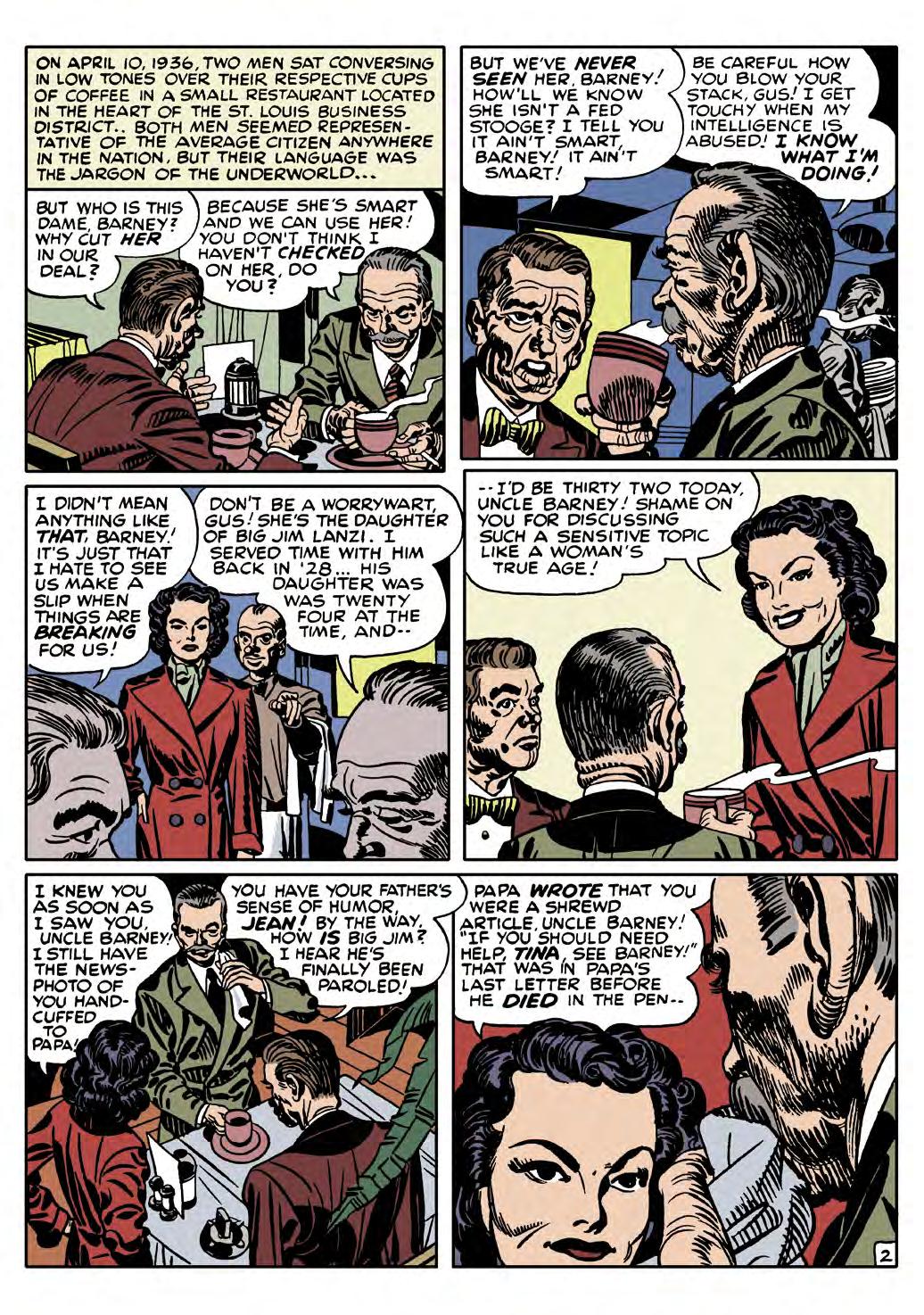

FOUNDATIONS 37 a never-reprinted crime story

INNERVIEW 52

Joe Simon speaks...

INNERVIEW 58 ...as does Jack Kirby!

KIRBY KINETICS 63 order and chaos in Kirby’s work

KIRBY OBSCURA 66 more 1950s treasures

TRAIL JUSTICE 68 the Silver Kid and the Black Rider

COLLECTOR COMMENTS 78

Front cover inks: MIKE MACHLAN

Front cover colors: TOM ZIUKO

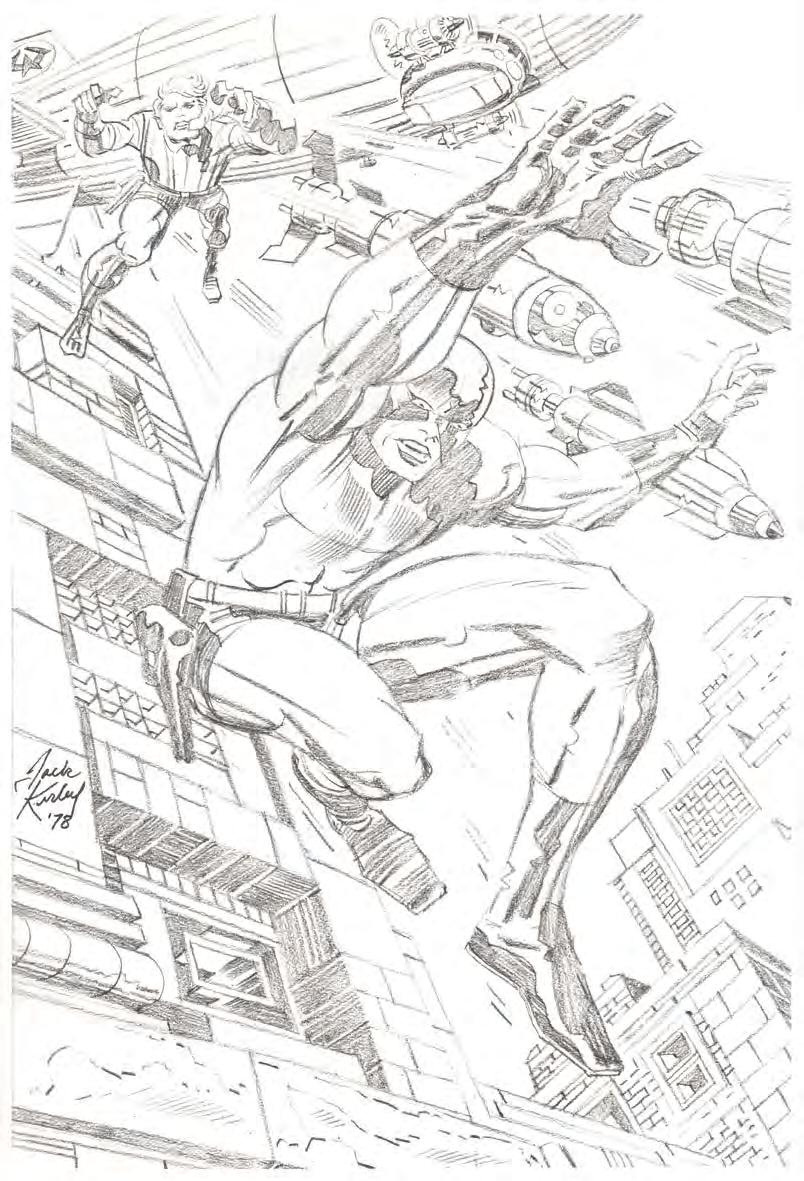

[right] Sandman and Sandy (sans mask), drawn for the 1978 Kirby Masterworks portfolio. Sadly, this issue’s cover inker Mike Machlan passed away earlier this year.

COPYRIGHTS: Boy Commandos, Challengers of the Unknown, Darkseid, Dingbats of Danger Street, Funky Flashman, Guardian, Houseroy, I Doomed The World, In The Days of the Mob, Izaya, Kalibak, Lightray, New Gods, OMAC, Orion, Sandman, Sandy, Superman, Terrible Turpin, Terry Dean, Terry Mullins, The Magic Hammer TM & © DC Comics • Black Rider, Cap’n Barracuda, Captain America, Doctor Strange, Dr. Doom, Fiery Mask, Galactus, Hulk, Human Torch, Invisible Girl, Mr. Fantastic, Nick Fury, Paste-Pot Pete, Roderick Kane, Ronan, Sandman, Sentinels, Sgt. Muldoon, Silver Surfer, Spider-Man, Steve Rogers, The Terrible Time Machine, Thing, Thor, Trapster, Vision, Wilhelm Van Vile, Wizard TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc. • The Black Hole TM & © Disney • Boys’ Ranch, Bullseye, Fighting American, Jail, Justice Traps the Guilty, My Date, Police Trap, Speedboy, Stuntman TM & © Joe Simon & Jack Kirby Estates • Captain Victory, Cyclone Burk, Galaxy Green, Satan’s Six, Sky Masters, Surf Hunter, Wonder Warriors TM & © Jack Kirby Estate • Blue Bolt, Johnny Reb & Billy Yank, Silver Kid TM & © the respective owner • Captain 3-D TM & © Harvey Comics

Don’t STEAL our Digital Editions!

THE ISSUE #87, SUMMER 2023 The Jack Kirby Collector, Vol. 29, No. 87, Summer 2023. Published quarterly (by law?) by and © TwoMorrows Publishing, 10407 Bedfordtown Drive, Raleigh, NC 27614, USA. 919-449-0344. John Morrow, Editor/Publisher. Single issues: $15 postpaid US ($19 elsewhere). Four-issue subscriptions: $53 Economy US, $78 International, $19 Digital. Editorial package © TwoMorrows Publishing, a division of TwoMorrows Inc. All characters are trademarks of their respective companies. All Kirby artwork is © Jack Kirby Estate unless otherwise noted. All editorial matter is © the respective authors. Views expressed here are those of the respective authors, and not necessarily those of TwoMorrows Publishing or the Jack Kirby Estate. First printing. PRINTED IN CHINA. ISSN 1932-6912 1 Collector C’mon citizen, DO THE RIGHT THING! A Mom & Pop publisher like us needs every sale just to survive! DON’T DOWNLOAD OR READ ILLEGAL COPIES ONLINE! Buy affordable, legal downloads only at www.twomorrows.com or through our Apple and Google Apps! & DON’T SHARE THEM WITH FRIENDS OR POST THEM ONLINE. Help us keep producing great publications like this one!

OPENING

SHOT 2

Contents

Mark Evanier

JACK F.A.Q.s

A column answering Frequently Asked Questions about Kirby

2022 Kirby Tribute Panel

Held at Comic-Con International: San Diego on July 24, 2022

Featuring moderator Mark Evanier, Frank Miller, Jeremy Kirby, Bruce Simon, Rand Hoppe, and Steve Saffel.

Transcribed by Karl Heitmueller Jr., and copyedited by Mark Evanier and John Morrow.

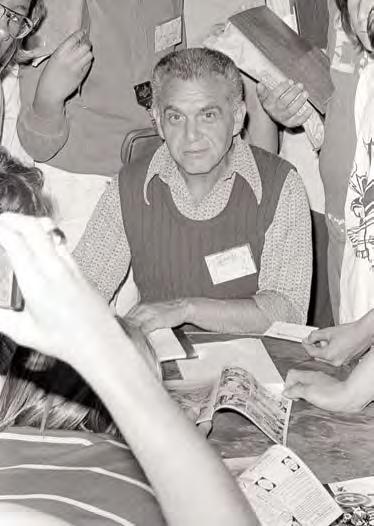

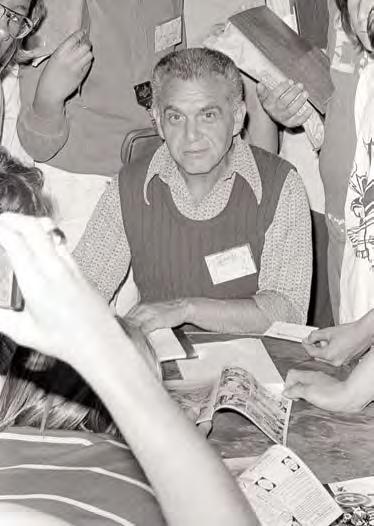

[above] Jack being mobbed by fans at a mid-1970s San Diego Comic-Con. All photos on this page are by Shel Dorf.

[top] Just for fun, here’s Mark Evanier from another early 1970s San Diego con. You haven’t changed a bit, Mark! (Can anyone out there send us images of each year’s San Diego Con badge, to help identify exact dates of these con photos in the future?)

[right] Nelson Bridwell, also mid-1970s.

[below] A very happy Hulk illo. The “H-5” designation implies that this might be an animation concept drawing for a potential Hulk cartoon—maybe for Ruby-Spears? (Or maybe it’s just a sketch for a sick friend who had trouble getting the child-safe lid off their prescription bottle...)

[next page, top] The 2022 panelists (l to r). Back row: Mark Evanier, Frank Miller, Steve Saffel. Front row: Jeremy Kirby, Bruce Simon, Rand Hoppe.

MARK EVANIER: Good morning, it’s Sunday, isn’t it? Wow. Well, it’s lovely to see one third or one half of all your familiar faces out there. This is the panel I look forward to most at the convention. Does anybody here not know that I’m Mark Evanier? Okay, thanks. (moderate applause) Either a lot or nothing, please. (laughter) I look forward to this panel because, first of all, I spend much of every convention talking about Jack Kirby. I spend much of my life talking about Jack Kirby. I hope each and every one of you, at some point in your life, meets someone who is so special, and is so important to so many people’s lives, that you could spend the rest of your life talking about them and have people say, “You mean you actually knew him, you actually met him?” I told a couple stories before about the reactions I got when people learned that I knew Jack Kirby, and they’re all 100% positive except for the production department at DC Comics, (laughter) and Mort Weisinger. (crowd murmurs) I met Mort Weisinger on his last day as the editor of Superman; literally the last day. A man named Nelson Bridwell introduced me to him, and Mort Weisinger remembered my name vaguely, and I said to him, “I had a lot of letters printed in your comics, and you and I had a brief correspondence, and you almost bought my first script.” And he said, “I wish I’d been able to,” you know, because what else can you say in those cases? And he said, “Are you working in comics now?” And I said, “Yes, I’m an assistant to Jack Kirby,” and the reaction was kinda like, (grunts and growls)… it’s hard to describe it, but it was not a positive reaction. Mort Weisinger had said, “Jack Kirby will work for DC over my dead body,” and that was pretty much what had happened. (laughter) He shook my hand again, and he walked out. He was there to sign off on the last issue of Superman to go to press that he had anything to do with, and he left DC after forty years that day. A couple of years later, I ran into Nelson Bridwell at a convention, and he mentioned that meeting to me. I said, “I’m surprised you remember that,” and he said, “Remember? I’ll never forget it. Seeing that man leave was the happiest day of my life!”

(laughter)

Anyway, we’re going to talk about Jack for a while here. We’re also going to talk about a fellow named Steve Sherman, whom some of us were also privileged to have in our lives. I’ve asked my friend, Bruce Simon… I’ve known Bruce longer than anyone in this room.

BRUCE SIMON: Since 1968.

EVANIER: Yeah, Bruce was a member of our old comic book club, and he was a good friend of Steve’s for a long time. Bruce has his own wonderful work he’s done as a cartoonist, but we’re not going to have time to talk about that today; we’re gonna talk about Steve. We also have on the panel Jeremy Kirby, Jack’s grandson. (applause) Isn’t it great that he’s on here carrying on the legend, the tradition? I get so sick of the word “legend,” I think it’s an overused word, it’s becoming so meaningless. You know, Paul Bunyan was a legend, Johnny Appleseed was a legend. These people did not exist, but they were legends. And I’m going to get him to talk a little bit about the reactions he gets when people find out who he’s related to. We also have—Frank Miller will show up when Frank Miller shows up. Oh, there’s Frank Miller! (Frank walks in, applause) Thank you my friend, have a seat here. Let me finish introducing other people. The gentleman in the hat

4

down there is the, uh, what’s your title? I always forget your title.

RAND HOPPE: I could go for Executive Director.

EVANIER: Executive Director of the Jack Kirby Museum and Research Center, Rand Hoppe. (applause) And the other end, this is my good friend Steve Saffel. Steve has worked over the years for most of the publishers in the business, and was heavily involved in representing Joe Simon on those Titan books that collected Simon & Kirby material. He was a good friend of Joe’s, somebody who helped Joe a lot, and Steve and I used to visit Joe together, and just extract comic book history from him. He’s another person who has the brag of, “Hey, I knew Joe Simon,” that was a very important thing.

STEVE SAFFEL: The thing with Joe, it was a little bit like Tuesdays with Morrie, but all comics. (laughter)

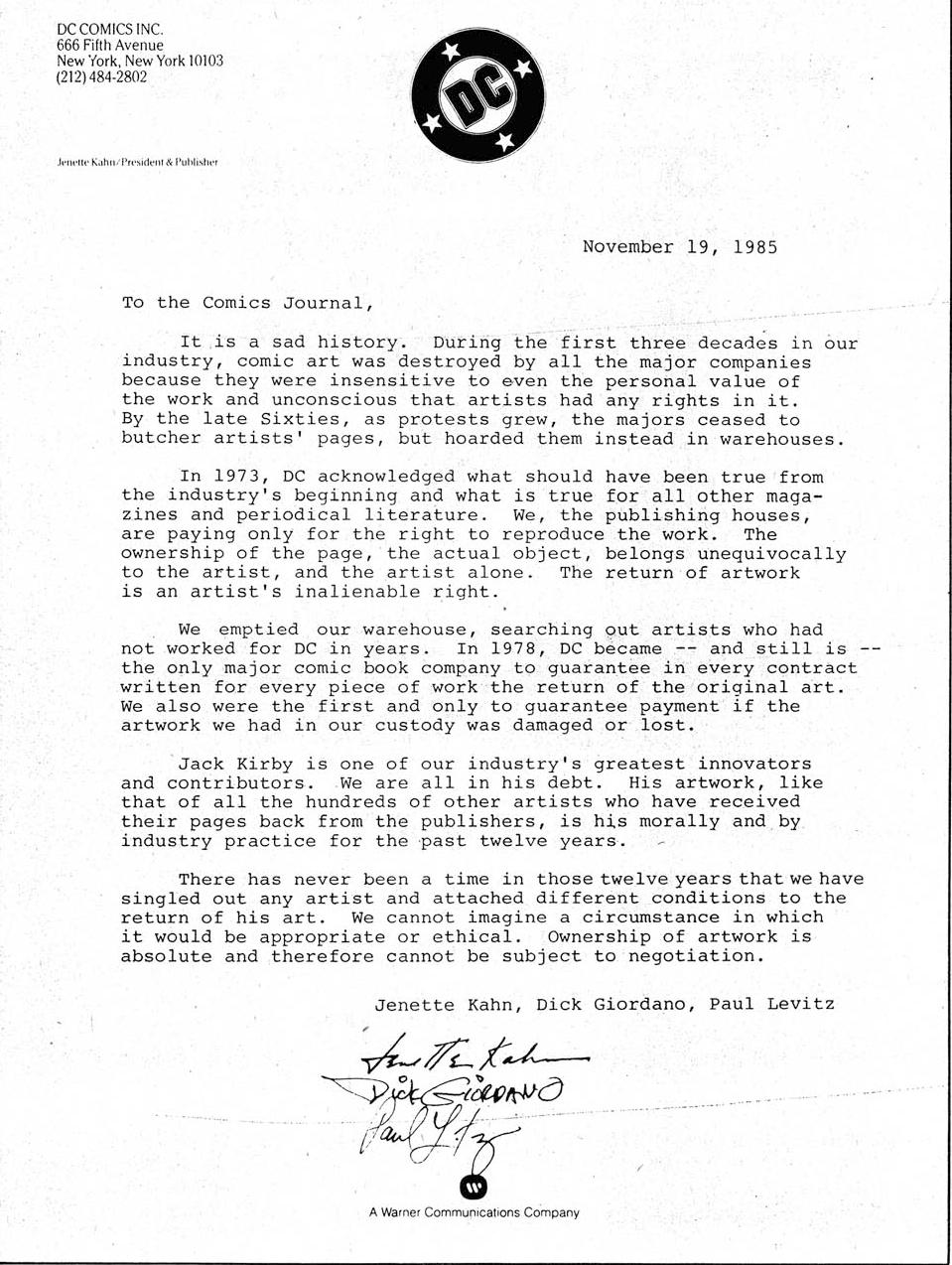

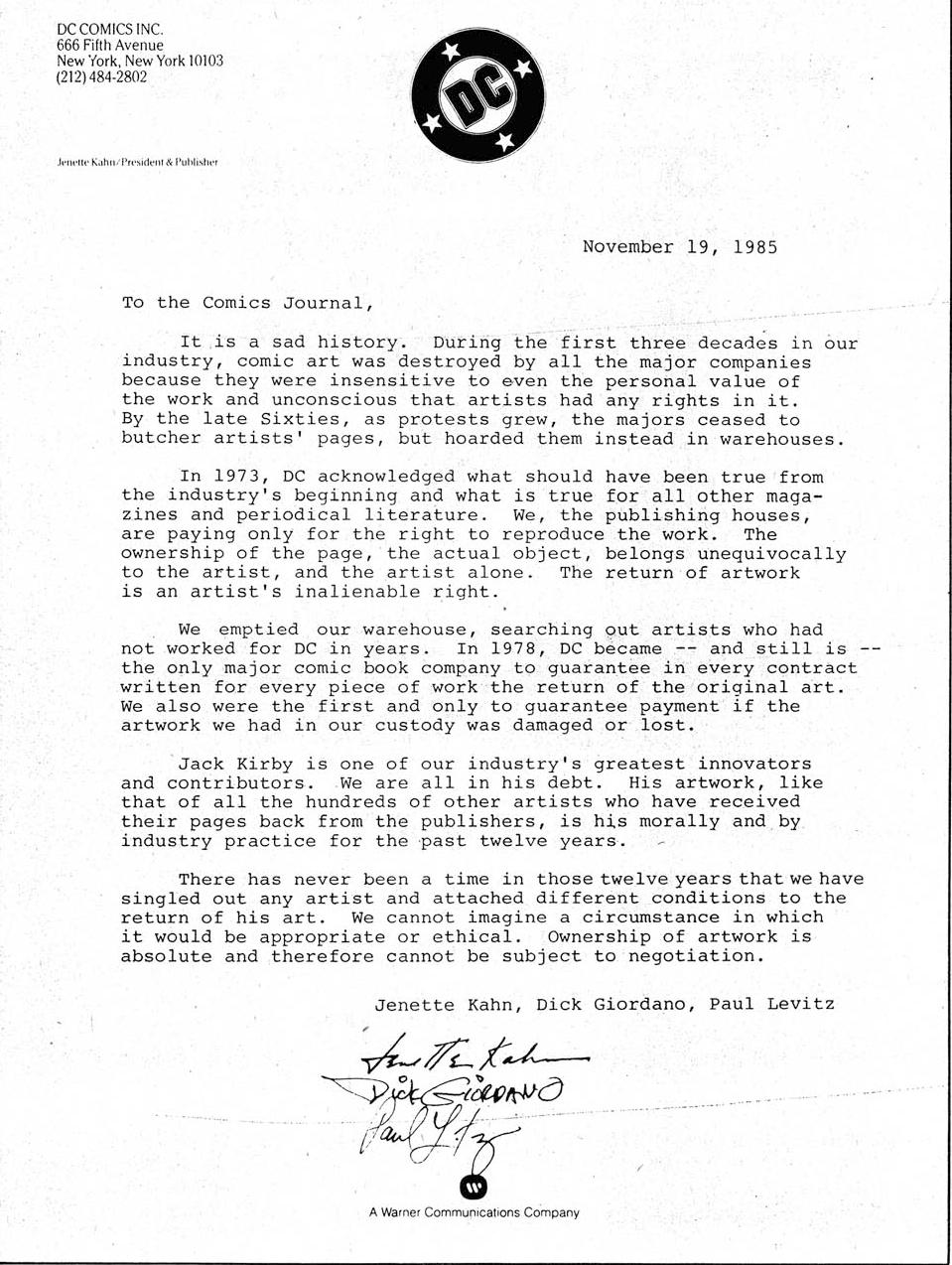

EVANIER: Joe was an amazing guy, if you ever got to see him talk. Now, I always start this with a little history lesson. Frank, don’t listen to this, because you’re in it. I want to take you all back to a

moment that I’m sure you’ve heard about, when Jack was fighting to get his original art back from Marvel. It was a very ugly thing, way uglier than it had to be. There was only one possible outcome: they had to give back to him whatever they had, but they dragged their feet, and they stalled, and they tried to get him to sign papers, and they tried to get him to relinquish rights that they claimed they already owned, and “We’d like for you to sign again that we own them”—it was very ugly. At one point, the main argument that Marvel was using to justify holding onto all this artwork—which they were returning to other people—was that it was industry custom. And you know you’re on shaky legal ground when you can’t produce a single piece of paper, and you have to say, “It’s an industry custom.” Marvel would not have accepted you doing work for them without a piece of paper signing away the rights, but it was industry custom that you already had, and “industry custom” didn’t cut it as far as lawyers were concerned, but it was all they had.

Now, Frank here, you all know what Frank’s done for comics, it’s an amazing track record. If he’d quit halfway through it, you’d still be praising his work, and he had a lot of clout in the business. He still has a lot of clout in the business, but he had a lot of clout, and people can use their clout for themselves, to enrich themselves, to further their lives, or they can use it to help other people out. Frank chose to use his clout to help Jack out a lot—at one point on a radio show in L.A. that laid out the case against Marvel very brilliantly, I thought Frank was wonderful on that. Then he went to the people at DC Comics, Jenette Kahn and Dick Giordano, and he got them to release a statement. When this panel is transcribed and printed in The Jack Kirby Collector, I hope this page is facing a reprint of that statement on the opposite page. [Taa-dahh! – editor] It was DC Comics declaring essentially that the way they’d always done business with artists had always been wrong; that “industry custom” was not to keep all the artwork. They knocked all the legs out from underneath Marvel’s principal argument, and essentially undermined all the things that previous managements at DC had claimed. I just stared at that letter when I first saw it, aghast. I could not have believed that DC lawyers would let them do that. It caused a lot of internal problems; remember that DC Comics owned MAD Magazine, and

5

Bill Gaines was still claiming that under industry custom, he owned all the artwork. But nevertheless, they did this, and I called up Dick Giordano and said, “I can’t believe you guys did that,” and he said, “Well, Frank asked us to.” And he didn’t have to tell me which Frank it was. And Frank, who could’ve used his clout to get more money out of DC…

FRANK MILLER: I did that, too! (laughter)

EVANIER: I not only respected Frank for the work he put on paper, I respected the hell out of him for what he did on behalf of Jack Kirby. And I would like you all to thank Frank Miller. (sustained applause)

Frank, do you remember that? Was it Jenette you went to first?

MILLER: It was Jenette I pretty much always went to, because she was someone from outside the world of comics, who was looking at them with fresh eyes, and was very much interested in the talent. And she in many ways ushered in what we called the British Invasion, with the leading figure of that being Alan Moore, but then Dave Gibbons and Brian Bolland and a number of others—which, you know, that was like the first British Invasion, and then Neil Gaiman has been a British Invasion all his own. So she was always looking for ways to brighten up DC’s position. She transformed the offices themselves. They were like a pop art celebration all of a sudden, instead of being dreary old offices. Physically, they just looked, like they had Zip-a-Tone wallpaper and such, and so you’d walk in and you felt like you were in a place that produced really cool material. But when I went, I was invited over to her office, for instance, to meet with her when I was doing Daredevil at Marvel, and I just started rambling to her about this crazy idea I had for a book called Ronin, and she changed a number of things about DC policy in order for us to work it out.

EVANIER: And she changed DC’s policy to get Jack back working for them, and to get some money off the Kenner toys of Darkseid and Orion and Mister Miracle. You know, the toys which the previous regime at DC had said would never happen because the characters were not licensable. “Why would anybody do toys of your New Gods stuff when we can sell Superman and Batman?”

MILLER: Yeah. And I’ve got to say that of all Jack’s material—and this is just my personal feeling; that when I grew up, believe me, as a Marvel fanatic, in awe of Galactus, and all of the Kirby and Ditko

6

From February 17, 1986, taken during the Hour 25 radio show on Pacifica Radio (KPFK-FM 90.7 in Los Angeles) featuring (l to r) Steve Gerber, Kirby, Mark Evanier, and Frank Miller, discussing Kirby’s original art battle with Marvel Comics.

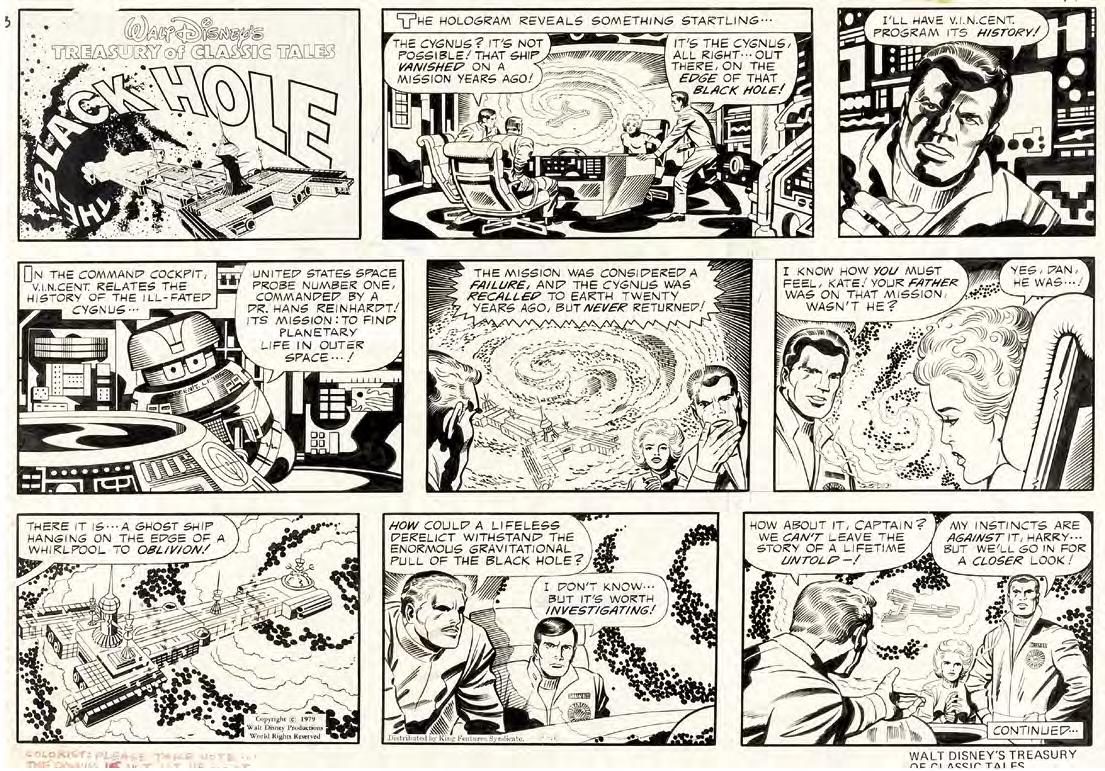

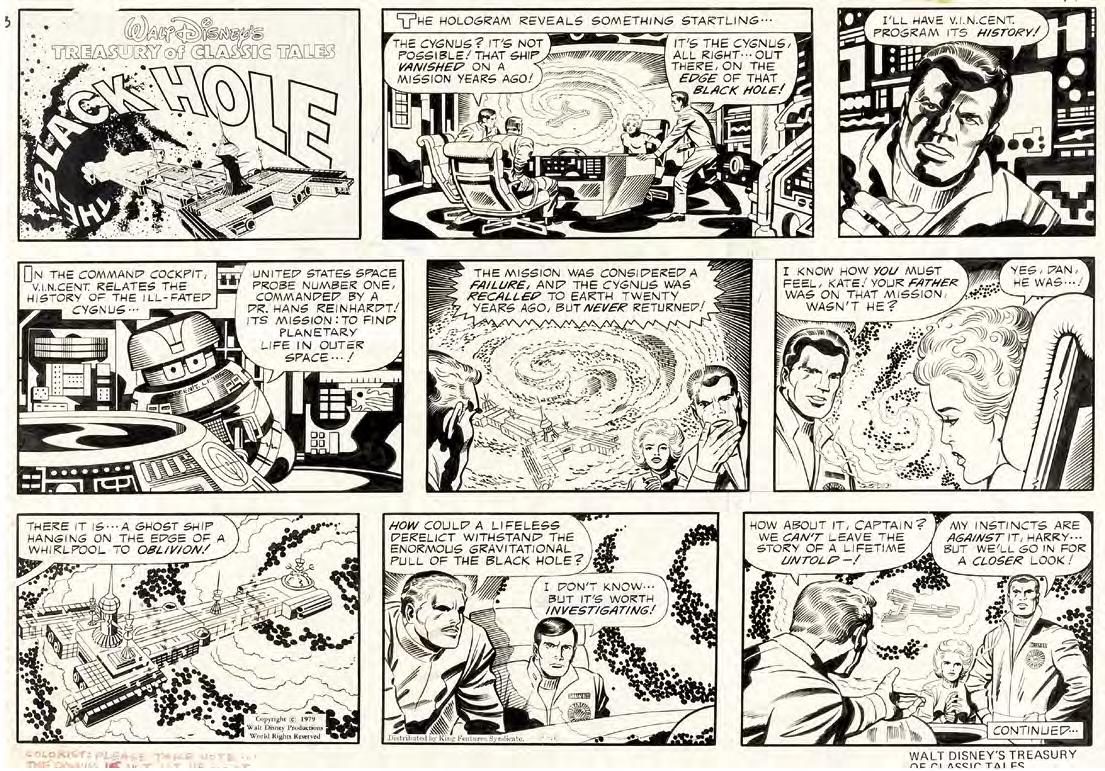

[above] September 16, 1979 Black Hole strip, based on the Disney film. Script and layouts by Carl Fallberg, inks and facial fixes by Mike Royer.

MILLER: Well, it’s the same way I couldn’t leave Will Eisner’s name off it. I felt that this was a big comic book movie and that it should celebrate that. I’m not gonna do that without Jack’s name on it.

EVANIER: Anyway, I’ve got thirteen minutes left to talk about Steve Sherman here. You don’t have to stay for this if you want to go.

MILLER: Ahh, I’ll hang out. I’ve got nowhere else to go. (laughter, applause)

EVANIER: Bruce, you and I are going to do a lot of this here. We had a comic book club in Los Angeles for a couple of years. We met at a place called Palms Recreation Center, 2950 Overland Avenue. Why do I remember this stuff? (laughter) I was the president, Rob Gluckson was the vice-president, Rob Solomon, Mike Rotblatt, Bruce Schweiger, we had a whole bunch of people there. This is where I met Bruce, and we became good friends, and I met this guy, Steve Sherman, and his brother Gary, who were largely inseparable for a long time.

SIMON: Totally inseparable.

EVANIER: In August of 1970, I think it was August, Steve picked me up at my house, and Bruce and Gary and Steve and I came down to the first San Diego convention together.

SIMON: Three hundred sweaty boys in a basement at the U.S. Grant

Hotel. (laughter)

EVANIER: Or, in other words, this room!

MILLER: That sounds really illegal. (laughter)

EVANIER: Let’s see if we can tell people what was wonderful about Steve.

SIMON: Wow. Steve had qualities that a lot of the other members of the comic book club did not have. He could drive a car… (laughter)

EVANIER: He knew when to shut up… (laughter)

SIMON: He needed to know when to speak, because he was a very quiet guy. His father, Eli, was an electrician, so consequently, Steve was the only one of us who knew how to run things. He could run a camera, he could figure out how to do color separations, he could MacGyver his way in and out of things, where the rest of us were like, (in nerd voice) “Oh, what’s going on with Doctor Doom?” So, as a practical matter—he was a few years older than the majority of the club members—he showed us what it was like to be a competent, nice, good guy. And he loved comics, and he loved working with Jack, and he also loved the world of special effects and puppetry, and that’s what he made his life’s work with his business partner and friend, Greg Williams. They opened a studio in North Hollywood called Puppet Studio, where they created creatures for a lot of movies that you’ve seen, I’m sure. Men in Black, all those little creatures running around. They worked on the Disney remake of Mighty Joe Young, working those gigantic hands coming in to grab people. They also did hundreds of television commercials. If any of you are old enough to remember O.G. Readmore, the ABC weekend specials; Mark wrote all of those, and Steve and Greg manipulated the O.G. Readmore puppet with an array of celebrities every week, which was hilarious…

EVANIER: Yeah,

1515

Sample Headline

Sgt. Muldoon: Villain or Hero— You Decide!

Everything is quiet, until—that voice pierces the air!

Funky Flashman has entered the room. TJKC #75 (Kirby & Lee: Stuf’ Said!) is an amazing, firsthand document of Marvel’s 1960s alchemy—and beyond. Rest easy, Stan and Jack, your history now belongs to the ages.

One mystery: In the summer of 1971, why did Kirby theorize Funky Flashman? The satire of Stan Lee in Mister Miracle #6 has fascinated fans for years. What would compel a forward-thinking visionary like Kirby

by Richard Kolkman

by Richard Kolkman

to look backward for inspiration? Sean Kleefeld (TJKC #62, page 44) raises the question: “I’m sure Jack’s anger and frustration with Lee hadn’t subsided, but why choose this moment to mock him?”

The answer begins when we look at Kirby’s appearances in Marvel comics. Kirby made five self-portrait appearances in Marvel comics in the 1960s/1970. The first two, Fantastic Four #10 (Jan. 1963) and Fantastic Four Annual #3 (1965) are scripted by Lee, and Kirby’s features are occluded or obscured in some way. He’s either turned away, shielded by his arm, or in the shadows. Kirby manages to appear and not appear! This was no accident.

Kirby appears next in Fantastic Four Special #5 (Nov. 1967). “This Is A Plot?”—Kirby scripts this, and the unpublished version of “The Monster” intended for Chamber of Darkness #4 (April 1970, see TJKC #13), in which Kirby and Lee appear at the end as unmasked warlocks. Kirby’s final appearance is his mute self-portrait for Marvelmania (inked by Royer) in 1969. The remaining few, assorted cameos of Kirby appeared in Not Brand Echh #11–12 and SubMariner #19.

Kirby left Marvel for National (DC Comics) in March 1970. (Let Kirby be free—and find himself!) The first “Funky” mention at Marvel, as Kirby leaves, comes at the end of June 1970’s Bullpen Bulletins page: “Who says mighty Marvel’s not taking over the whole funky world?” (Street date: March 1970)

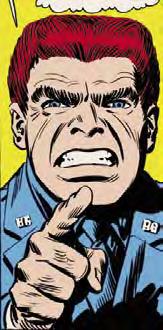

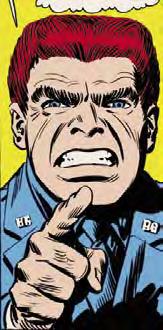

As always, the times they were a’changing. In Captain America #139 (July 1971), we are introduced to Sgt. Muldoon. Fashioned by Stan Lee and John Romita to be Steve Rogers’ C.O. (while Cap works undercover for the police), Muldoon is clearly based upon Kirby—affectionately, down to the gruff exterior and chewed cigar. Kirby has always been associated with anger. The Thing, Kirby’s metaphoric self-portrait, is appropriately named: Benjamin (Kirby’s father), J. (Jacob), Grimm (means “anger” in German). (Note: this issue also features the debut of Leila—Sam Wilson’s dynamite doll sweet sister! Kirby features Leila in Roz’s Valentines’ Day Sketchbook—but not the Human Torch!)

Just before Muldoon appears, “The Badge and the Betrayal” (Captain America #139) features a swipe of Kirby’s Cap and Bucky from Captain America #105. This story, featuring a Kirby-

17

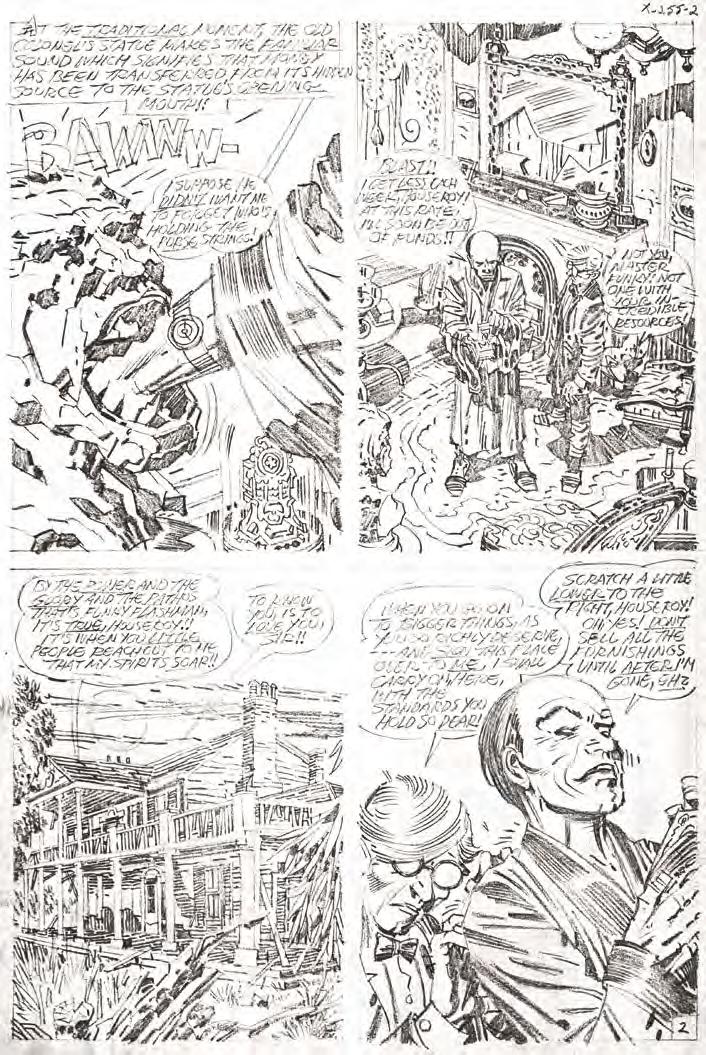

cop OUT

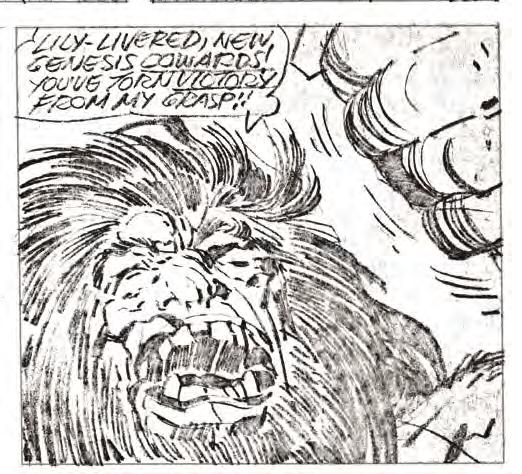

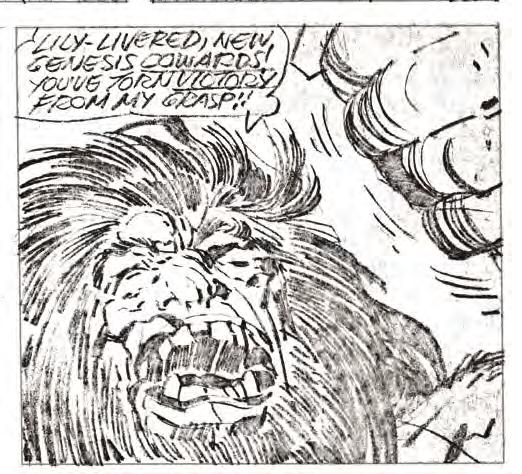

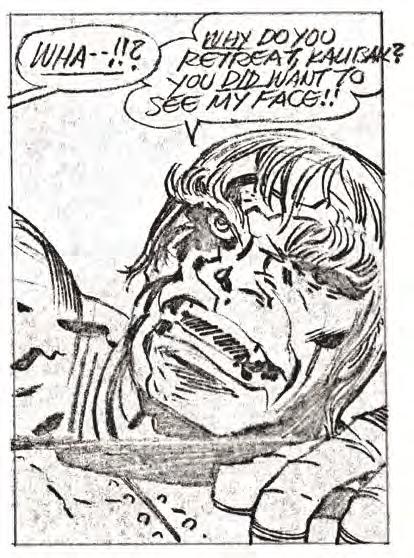

[below] Pencils from Mister Miracle #6 (Feb. 1972). If Stan was going to parody Jack as Sgt. Muldoon in Captain America #139 (July 1971, right), Jack would up the ante with Funky Flashman.

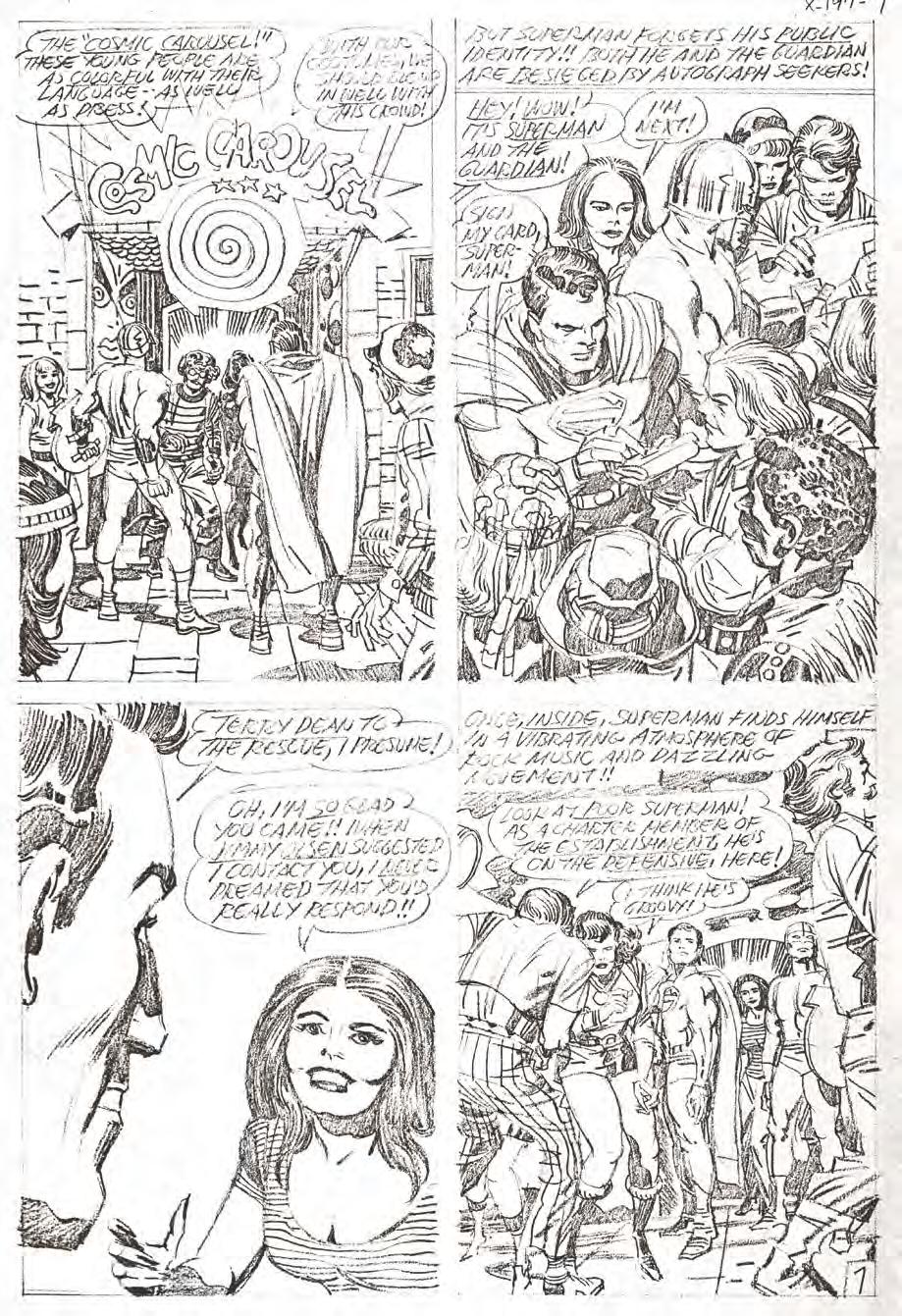

Gallery SUPER COPS

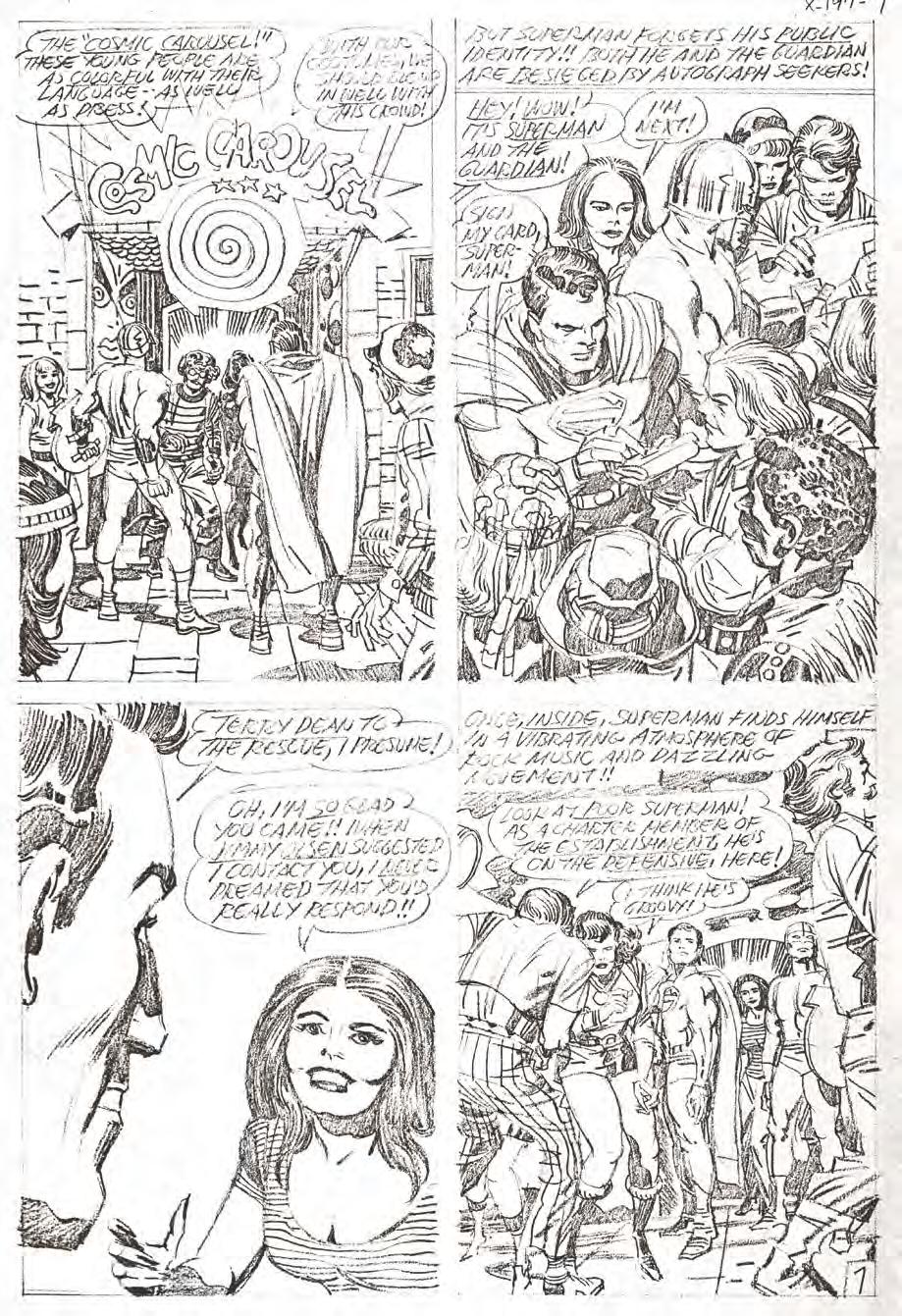

[right] Jimmy Olsen

#144, page 7 (Dec. 1971)

Solid pencils from this weird part of Kirby’s Jimmy Olsen storyline where cloned police officer Jim Harper’s alter ego as the Guardian vanishes from the series without warning. Panel 4 is interesting in that we see Kirby’s use of flash lines, even on a small scale, where they surround Terry Dean and give the largely static panel more life. That Kirby’s instincts were right is shown by the published page, where we see inker Colletta has taken one of those shortcuts he’s often maligned for—and not only blacked out the flash lines, but the whole door, losing Terry Dean altogether. Strangely, in other parts of the panel, Colletta added solid blacks where Kirby had light spots, and lost blacks that Kirby included.

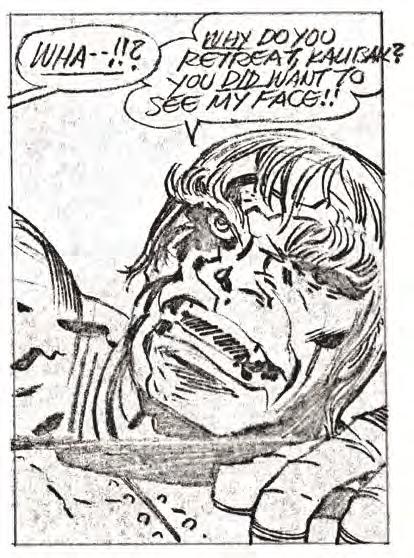

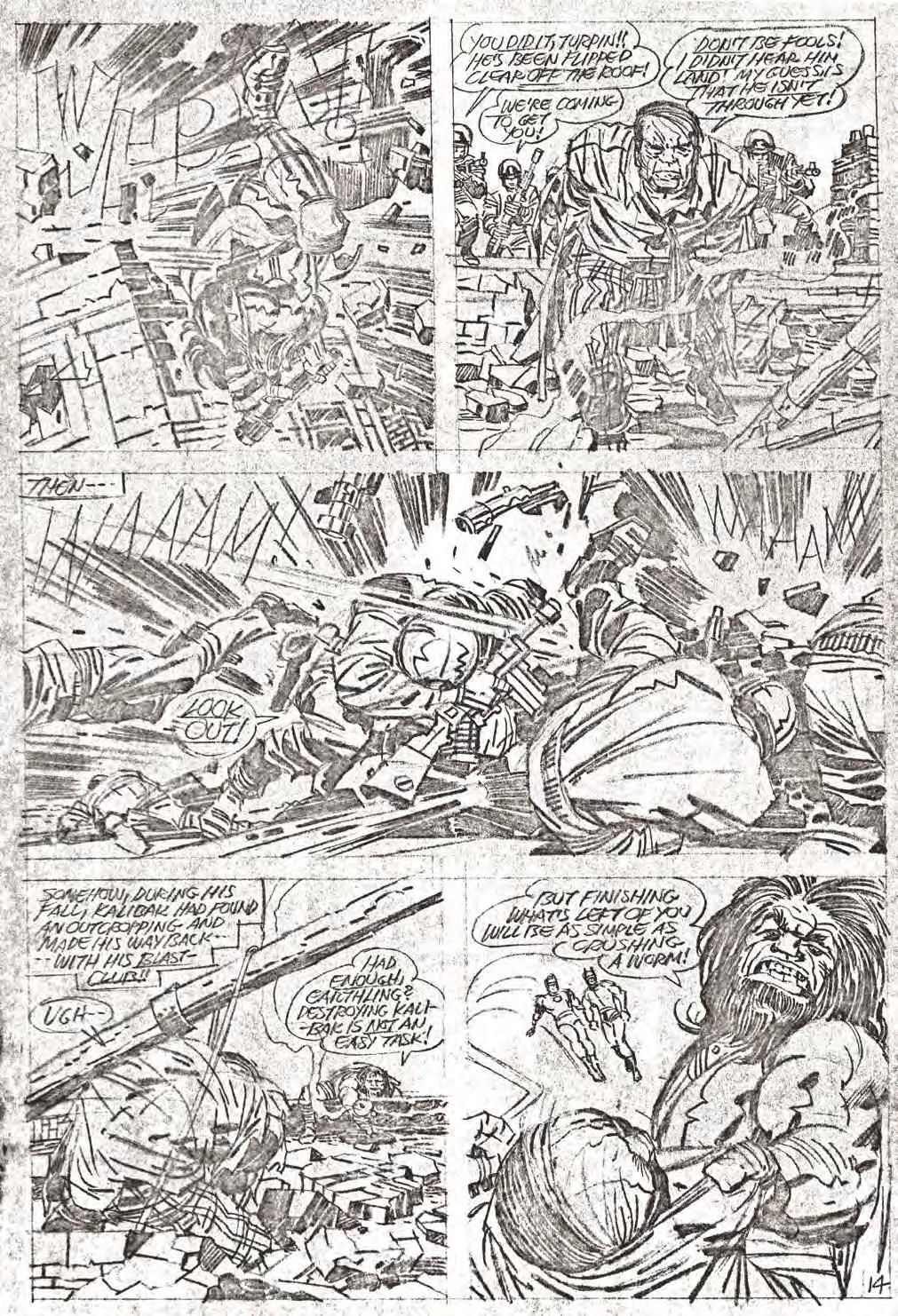

[next page] New Gods

#8, page 14 (May 1972)

A perfect example of Kirby as the master of power and tension. As well as the shattered but powerful figurework and the explosive flash lines, even minor details add to the overwhelming atmosphere. In panel 2, the rising, curling smoke and broken pipe subliminally add tension in the way a coiled snake does. In panel 4, not only is there the battered figure of Sgt. Dan Turpin—the focus the reader sees— but the broken pole and dislodged wire subtly continue the tension. A note about the inked version: in panel 1, Kirby has Kalibak’s foot in front of the “Whom!” (a sound effect saying “Whom!”?), but letterer Royer covered the foot with the letters. Does it make a difference?

20

Drawing law and order in Kirby’s work, with commentary by Shane Foley

21

Twice-told Kirby covers,

Incidental Iconography

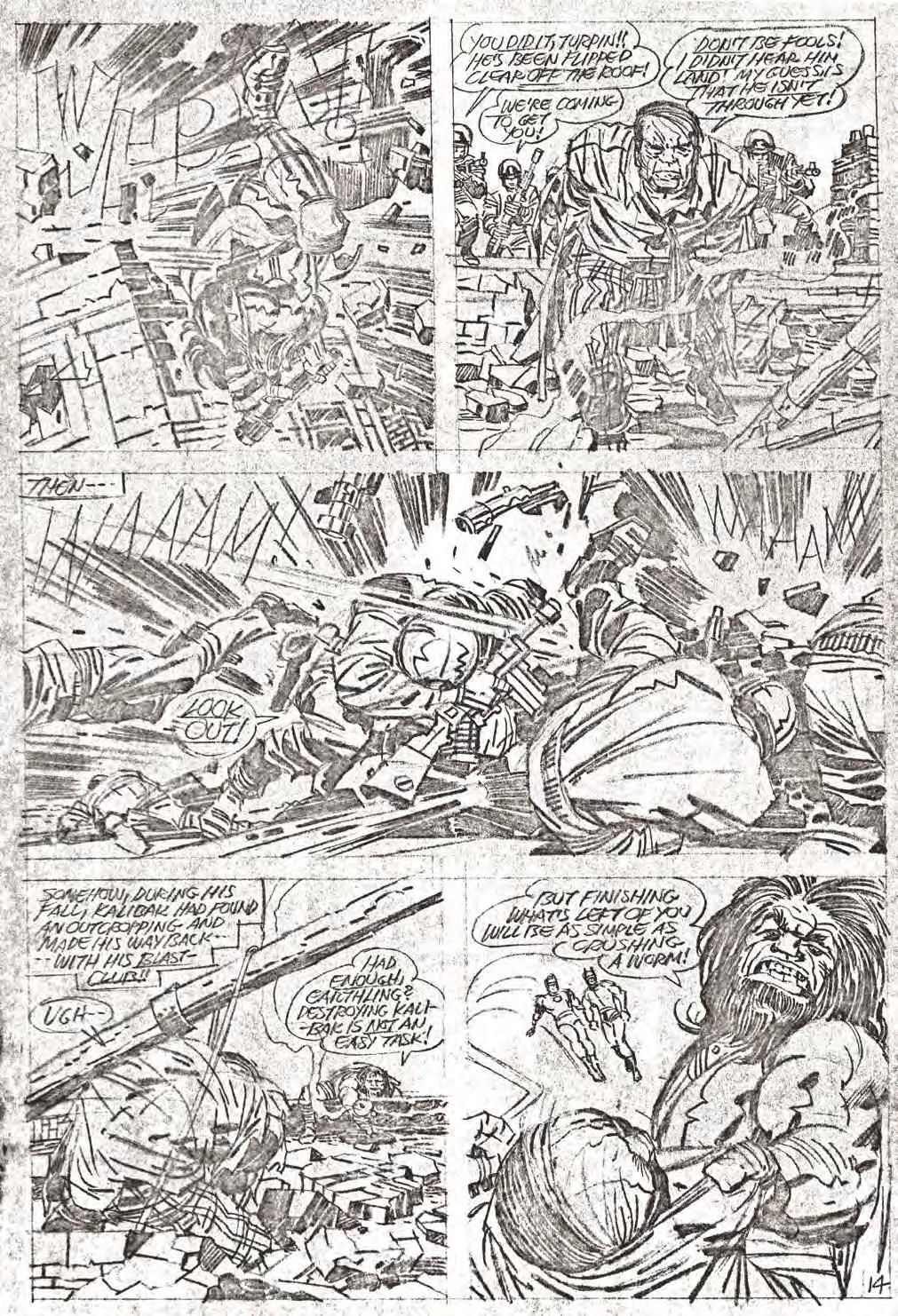

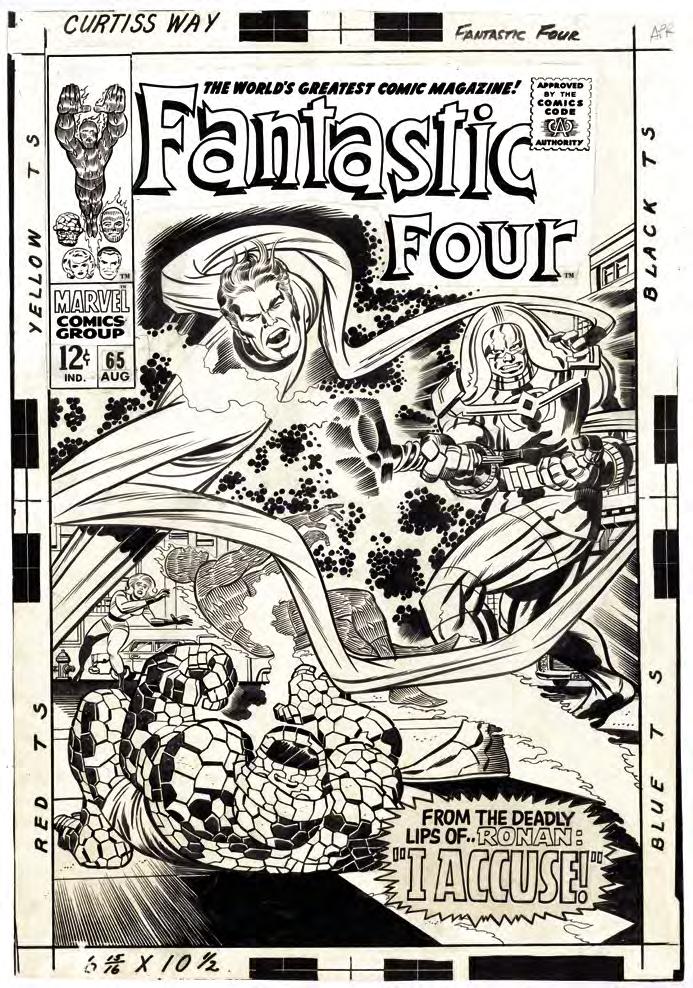

Decades before Judge Dredd gained prominence as the embodiment of judge, jury, and executioner, that role had been taken up by Ronan the Accuser. And even though Jack only drew him

the character’s design, and dials it back as the issue rolls on. Ronan first appeared in Fantastic Four #65. The team had defeated an “all but forgotten” Kree Sentry in the previous issue, and so the Supreme Intelligence dispatched Ronan to deal with them so that everyone in the galaxy would be taught “that none may destroy a Sentry of the supreme Kree race!”

Although Ronan is featured prominently on the cover , the first drawing of Ronan is likely his appearance on page 5 of the story. (Recall that covers at this time were usually drawn after the story artwork had been completed.) Though drawn relatively small, it is clear that Jack opted to make Ronan pretty heavily armored. His arms and legs have a banding on them indicative of how Jack often drew flexible armor, and his headpiece is a helmet that almost completely covers his head, and anchors over his shoulders in such a way that prevents anyone from either snapping his neck or choking him. (Although this also limits the range of motion—Jack never draws him turning his head left or right, and only minimally up and down. Ronan is always shown moving at his torso to look anywhere that isn’t directly in front of him, much like Michael Keaton does in the 1989 Batman movie.) There also appears to be some additional threetiered flexible armor at the back of Ronan’s neck piece, as well as a chevron design that circles around the edge. Neither of these continue around to the front, both ending at the top of the shoulder. In two panels, Jack does seem to have recognized the apparent discrepancy and drawn them in a way that implies a deliberate end to the design, but it does seem a little arbitrary to me—as if Jack designed the front and back of the character independently and couldn’t think of a satisfactory way to transition between them. The designs also get simplified as the story continues on, with the three tiers dropping back to two-and-a-half on page 11, and only two from page 17-onwards. The chevron, too, gets less complex towards the end of the issue.

Perhaps more noticeable, though, is the inconsistency in Ronan’s leg and arm armor. The leg-banding seen on page 5 drops to only two lines cutting across Ronan’s legs on the following page, and vanishes entirely on page 13 [right]. It does reappear on page 17, only to vanish again on the next page. The arm-banding seems more intentional in the design, but it also disappears and reappears seemingly at random. From the

...At Fame!

An ongoing analysis of Kirby’s visual shorthand, and how he inadvertently used it to develop his characters, by Sean Kleefeld

Oneshot... 28

Hot Docs N

Legal-(Dis)ease

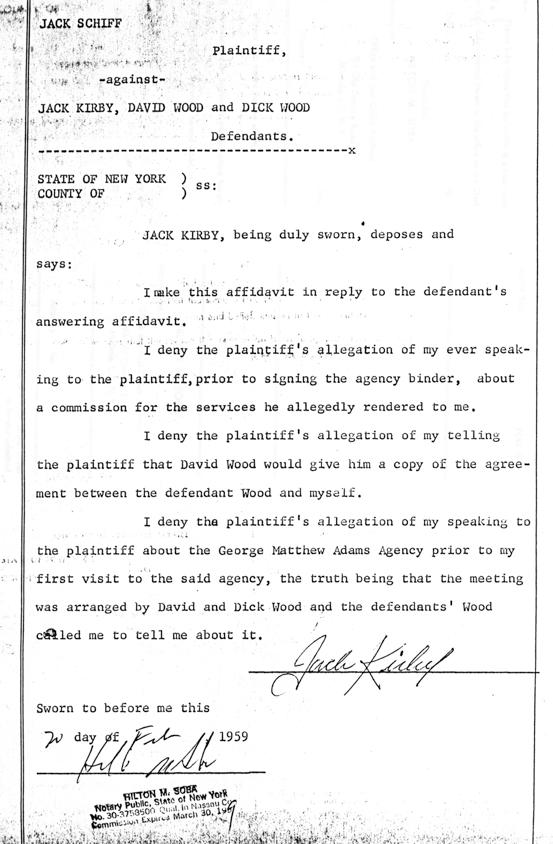

Kirby’s days in court (or close to it), presented by John Morrow

obody enjoys being involved in a legal dispute (well, other than highly paid attorneys), and that was especially true of Jack Kirby. He’d much rather sit at his drawing board and create all day, than have to be deposed in a legal matter. But with a career as lengthy as his, it was bound to happen—and indeed, did numerous times throughout his career.

Simon’s business expertise to keep him out of legal hot water. Jack’s February 10, 1958 agreement to produce the newspaper comic strip Sky Masters with Dick and Dave Wood was the start of an unpleasant episode for

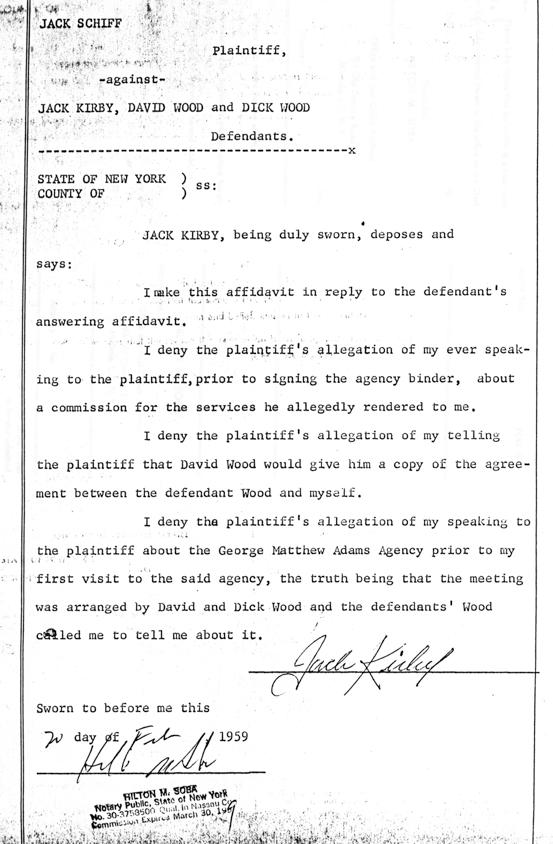

[right] Jack’s February 20, 1959 affidavit, outlining his defense against DC editor Jack Schiff in the Sky Masters lawsuit, which he eventually lost on December 3, 1959.

[next page] Kirby’s February 1, 1960 of what he earned from the first 15 months of the Sky Masters strip. Shown below is the September 17, 1958 strip, and the April 18, 1959 installment is atop the next page. Both were inked by Wally Wood.

His earliest legal skirmish was over Captain America’s similarity to Archie Comics’ own patriotic character The Shield in 1941. That was worked out with a meeting in Archie co-founder John Goldwater’s office, which involved Joe Simon, Kirby, and Timely Comics publisher Martin Goodman. The end result worked in Jack’s favor, as the compromise was to alter Cap’s shield to have a circular shape starting with issue #2, so it wouldn’t mimic the Shield’s chestplate. This opened up new creative possibilities for tossing it, which Kirby would use to its fullest in his 1960s work. Ironically, Goodman would soon intentionally shortchange Joe and Jack on their share of Captain America royalties, which led to the duo moving to DC Comics.

Another favorable outcome came from Simon & Kirby’s 1950s dispute with Crestwood Publications (also known as Feature Publications and Prize). Publishers Teddy Epstein and Mike Bleier refused to pay Joe and Jack when they repackaged an existing story for publication as new material. That dispute led to a review of Crestwood’s accounting records, which showed Joe and Jack were owed $130,000 in royalties by the company. Crestwood eventually paid them $10,000, and S&K even created an unproduced screenplay called “Fish In A Barrel” based on the kerfuffle.

After Joe and Jack parted ways after the collapse of their Mainline Comics company in 1956, Kirby certainly could’ve used

30

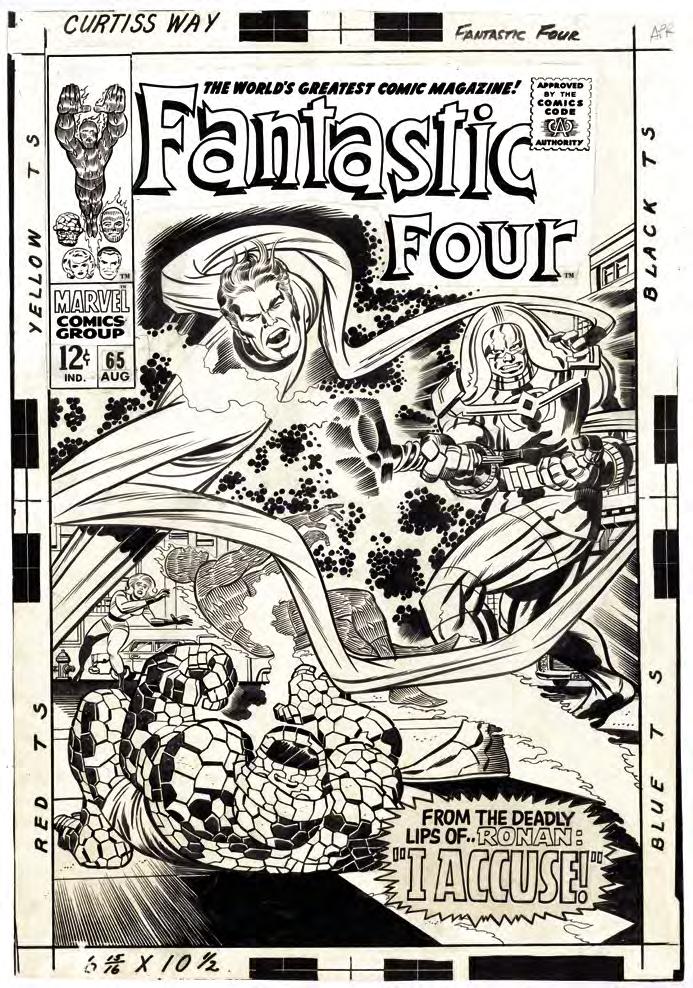

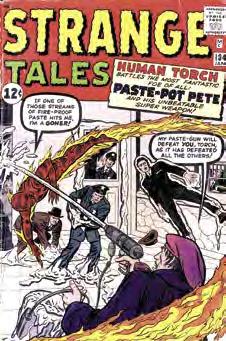

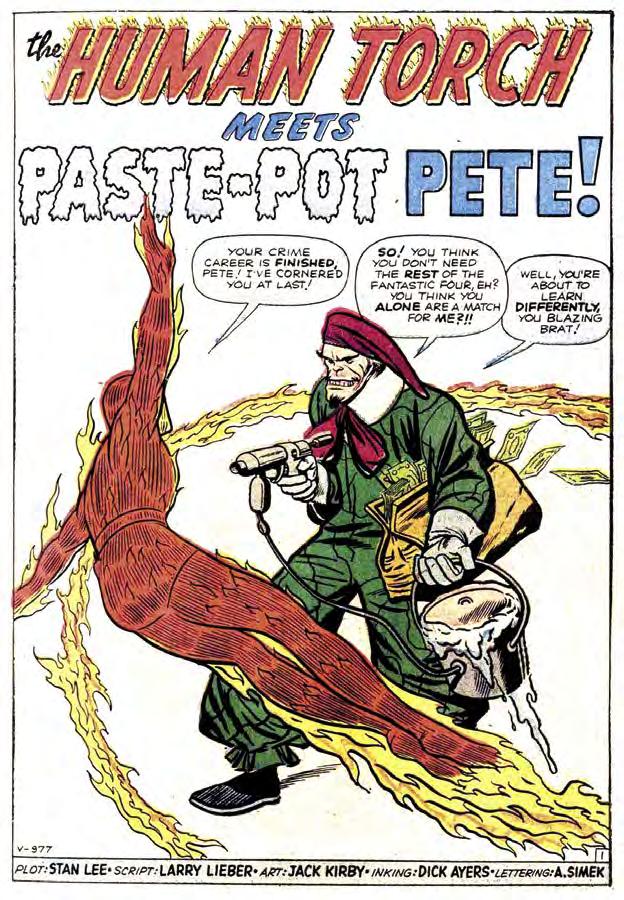

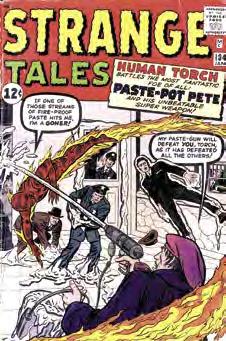

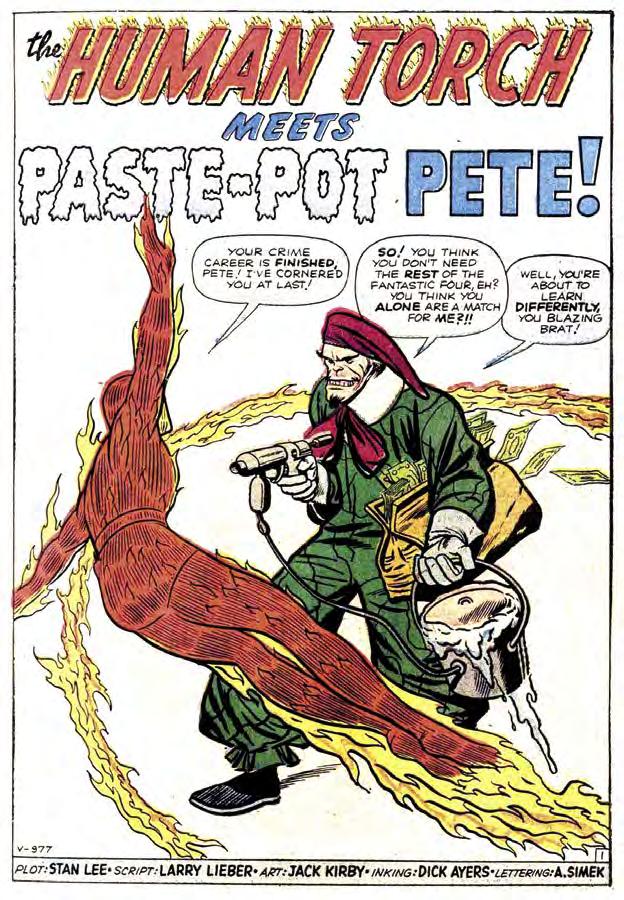

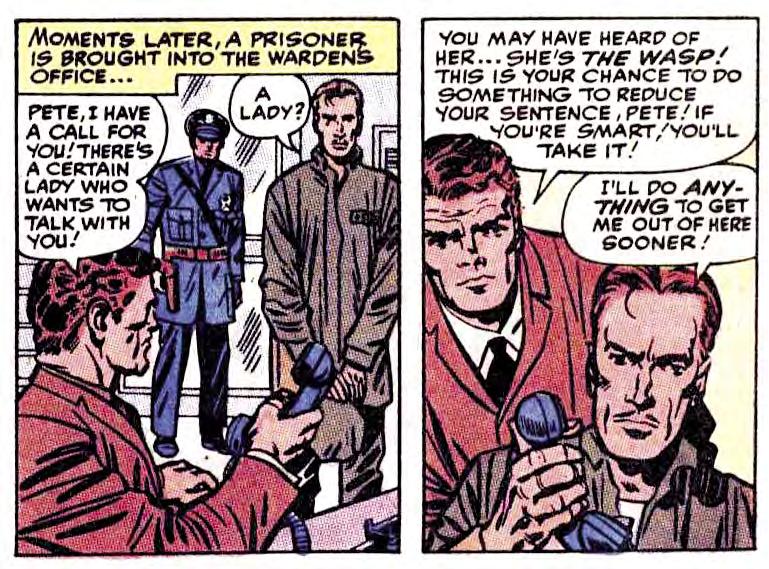

[below] Cover and splash page from Strange Tales #104 (Jan. 1963), where Paste-Pot Pete debuted.

[next page, left]

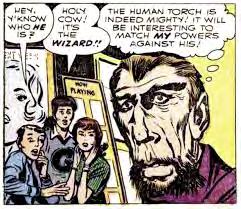

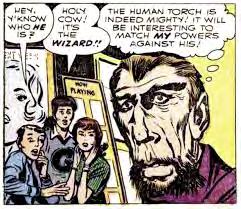

That’s definitely the Wizard (not Paste-Pot Pete) in this sequence from Avengers #6 (July 1964). Which begs the question: Did Jack draw the wrong character, or did Stan call him by the wrong name?

[next page, right]

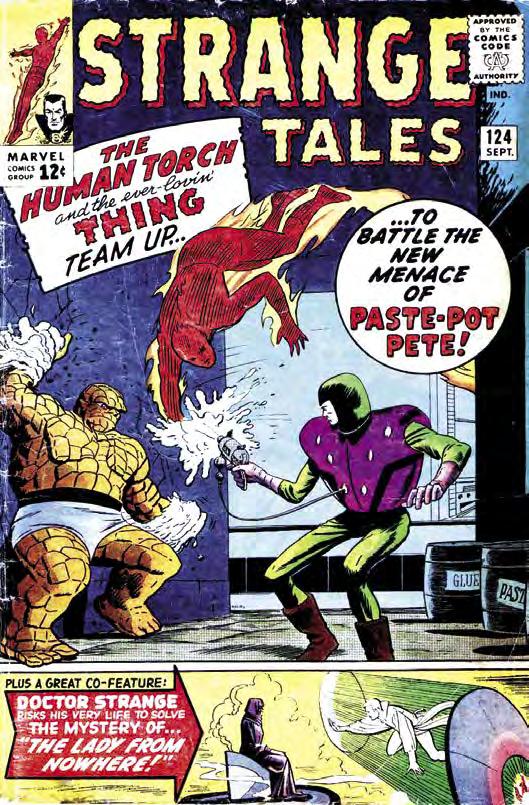

Dick Ayers depicts Pete’s upgraded design on the cover of Strange Tales #124 (Sept. 1964).

Over the course of his long career, Jack Kirby created a great many memorable creations. Some will probably long endure, but just as often as not, he created what I like to call his “wild hair” characters. These were semi-comical figures who seem to have emerged from some particularly bizarre cranny of his imagination. I’m thinking of such oddball ideas as the Human Top, Egghead, and Diablo.

by Will Murray

bad man-agement Who the Heck redesigned Paste-Pot Pete?

gripping the thin handle of your open hardware-store bucket with the dangerous super-sticky paste slopping over the rim. That’s what Jack Kirby designed back in the early days of Marvel’s resurgence, and that’s what Paste-Pot Pete attempted in his first foray. Although thwarted by the Torch—or was it the other way around?—the baggy-pantsed marauder soon graduated to grabbing an experimental US “delta-cosmic” missile in the hope of selling it to the Reds— that’s Communist Russia, not the Cincinnati ball club. The Torch foils this daring scheme, but Pete escapes capture. This gave him the distinction of being the first Human Torch foe to avoid prison. Obviously, he was being set up as a recurring opponent.

For unknown reasons, villains in the “Human Torch” strip running in Strange Tales between 1962 and 1965 more often than not were extreme caricatures who possessed unusual facial features and cranial constructions, and usually sported outlandish hirsute adornments. The Wizard was first and foremost, and Wilhelm Van Vile (the Painter of 1000 Perils), followed by Cap’n Barracuda [all above]. Come to think of it, the mustached Acrobat also belongs in this class of crooks. Some of these characters could almost be viewed as cousins—or at least guys who shared a common barber. One of the most peculiar––at least to my mind––was the early Human Torch foe who originally called himself Paste-Pot Pete.

I don’t know what Kirby was thinking back in 1962 when he designed this ridiculous character. For those who don’t know or may have forgotten, Paste-Pot Pete was an outlandish personality tricked out in some type of house painter’s coveralls, replete with exaggerated beret, elaborate ribbon bow tie, and weird chin whiskers, who carried around a pistol that fired a special formulation of powerful paste which was fed by a metal paint-pot Pete toted around.

I can’t imagine attempting to rob a bank with one hand on the grip of your paste pistol and the other

32

Readers with long memories might have wondered back in 1962 if Paste-Pot Pete wasn’t a fugitive from an unpublished issue of Fighting American. I still ask that question myself.

The Original Captain Sticky

A few issues later, Paste-Pot Pete returned, this time teaming up with the Torch’s main recurring foe, the Wizard, for a double rematch. It did not go well. Even though Pete had broken the Wizard out of jail, the scientist’s abrasive ego complicates and finally sabotages their plan to implicate Johnny Storm as a spy. This time, both malefactors ended up behind bars.

Ernie Hart, writing as H. E. Huntley, scripted this story from a Stan Lee plot. Dick Ayers soloed on the art. Kirby only drew the cover, which depicted the same clownish Paste-Pot Pete he originated.

The next time Pete is seen is approximately a year later in the pages of The Avengers #6, when the Avengers tackle another character who uses a powerful glue known as Adhesive X. This, of course, is Baron Zemo, the Nazi-era super-villain who was responsible for

instead, then neglected or didn’t care enough to have the character’s face corrected. Either villain was hypothetically capable of solving the Avengers’ sticky predicament.

This is another mystery of the Silver Age—one that will probably never be satisfactorily explained.

Bucky’s death and Captain America’s long icy suspended animation, and who found himself permanently wearing a hood because his head was splashed by his own unbreakable adhesive, which was a version of Superglue long before products like it and Gorilla Glue were invented. That’s Jack Kirby being ahead of his time as usual.

One could say that Baron Zemo is something of a more dramatic re-imagining of Paste-Pot Pete.

Anyway, when Captain America and Giant Man became unbreakably trapped by Adhesive X in Avengers #6, the imprisoned Paste-Pot Pete was released in order to formulate a super-dissolving solvent to release them. This wins Pete an early parole.

One of Kirby’s most famous goofs in the early Marvel days was the fact that he did not draw Paste-Pot Pete in that Avengers issue. Instead, he apparently depicted Pete’s former confederate, the Wizard, who also sported an unusual goatee and had a strikingly narrow face. But this character doesn’t exactly look like the Wizard, either. He’s much more handsome and his chin is clean-shaven. He does have a pencil-thin mustache—which neither the Wizard nor Paste-Pot Pete ever wore!

Although Kirby was infamous for making artistic mistakes (such as not drawing the correct number of buttons on Thor’s costume from panel to panel, and depicting a Skrull spaceship entirely differently from page to page as he did in Fantastic Four #2), since Kirby was as much a plotter of the stories as was Stan Lee––if not more so in many instances––it would not surprise me if it was Kirby’s idea that the Wizard provided the Avengers’ salvation and Lee decided as editor and scripter to make him Paste-Pot Pete

A New Glue Review

Having been paroled in Avengers #6, Pete returns a month later in the pages of Strange Tales #124, not reformed, but determined to resume his interrupted life of crime. Pete went back to being a solo act. Evidently, he had had enough of the ingrate Wizard during their brief felonious flirtation.

Stan Lee was back, now scripting solo. He, or perhaps vocal readers, recognized the ridiculousness of this Human Torch antagonist, and Lee did something about it. Deciding that he was seen by the public at large as clownish, Pete apparently shaved his goatish goatee and adopted a completely redesigned outfit with a much enlarged and improved reservoir for his miraculous paste, which he used to “paste” the Human Torch and the Thing in a credible way.

The redesign was so striking that you could hardly recognize the original Paste-Pot Pete under the black face-framing hood, bulky chest plate, and thick boots. The key to the redesign was that Pete now wore a rectangular contraption on his upper body, vaguely similar to Iron Man’s original chest plate, but much thicker and filled to capacity with his special paste solution. By plugging the feed hose from his new streamlined “paste jet pistol” into any one of several outlets in this bulletproof “vest,” this inventive villain could now access his paste solution from a less sloppy and evidently spillproof reservoir. His boots were also filled with paste, and the soles

33

Foundations

37

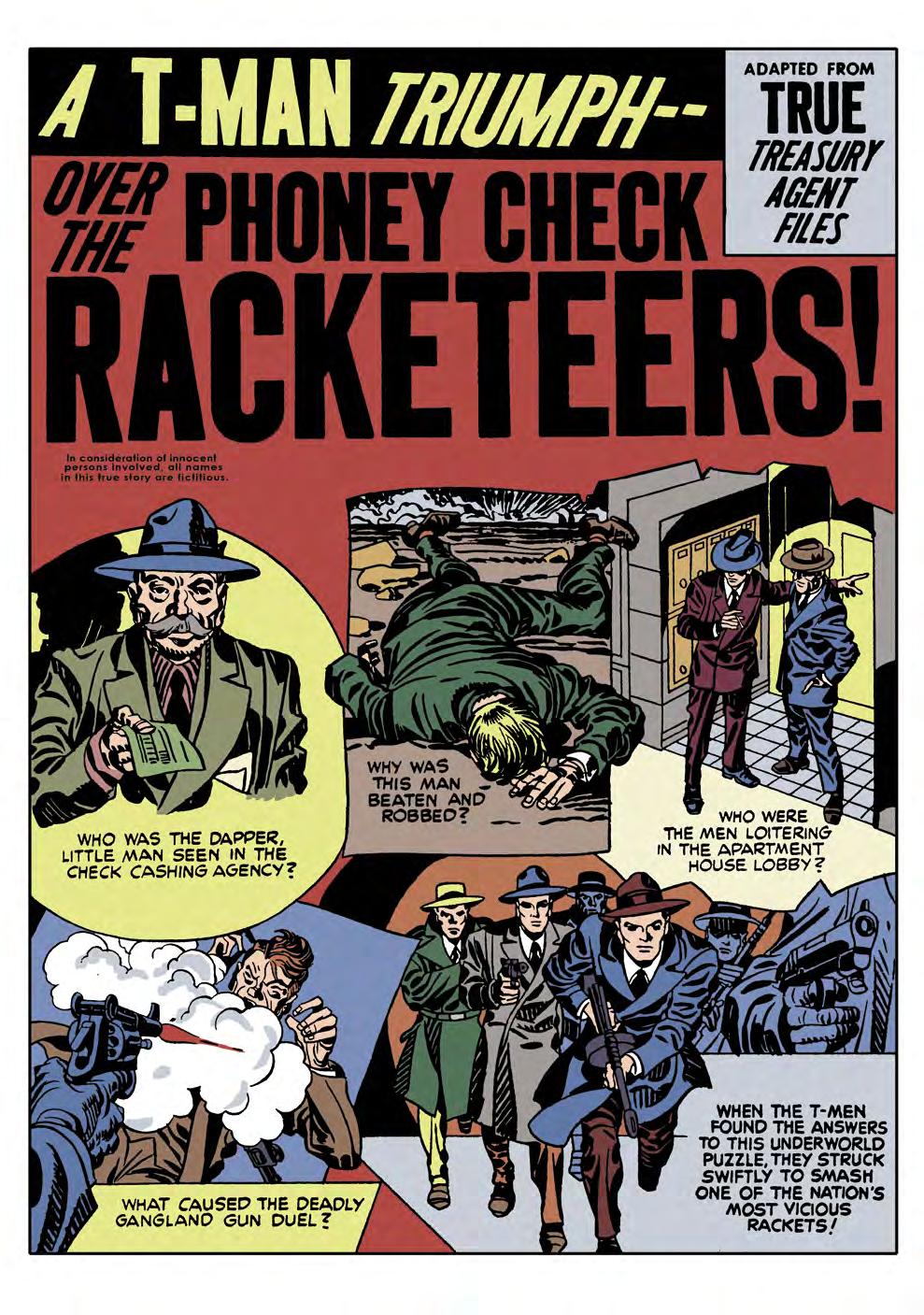

Here’s Simon & Kirby’s never-reprinted story “Phony Check Racketeers” from Justice Traps The Guilty #7 (Dec. 1948). Art restoration and color by Christopher Fama.

38

INNERVIEW

[below] Stuntman was a victim of the postwar comics glut Joe Simon discusses here, and back in TJKC #61, we published the first seven pages of the unpublished Stuntman #3 story “Terror Island” featuring the villain The Panda. To complete the story, we still need pages 8 and 14 (and higher if page 14 isn’t the last page of the story). We also need all the pages from the other unpublished Stuntman story “The Evil Sons Of M. LeBlanc.” Help us finally get these lost stories into print!

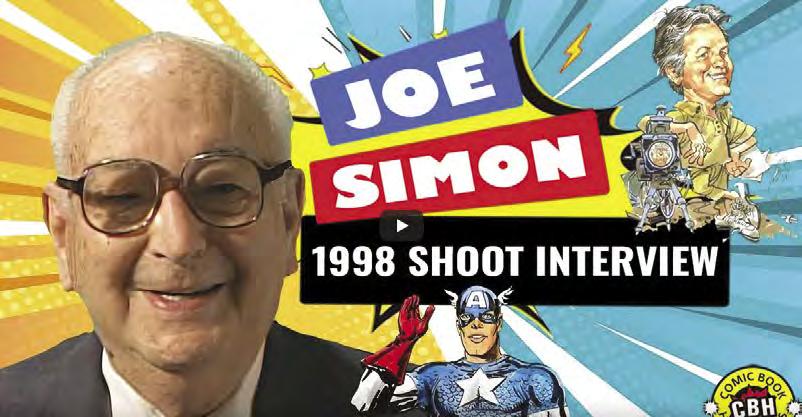

[See David’s actual video interview on YouTube at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BrJ8nynNIQ0]

DAVID ARMSTRONG: Where were you born?

JOE SIMON: In Rochester, New York, and I grew up in Rochester. I got my first job there when I was 18 years old, for the Hearst Newspapers, Rochester Journal American. Course they’re out of business now, ’cause

Hearst closed his chain of newspapers, one after the other, as I moved from one to the other. I stayed there for a year, and then Hearst closed them and finally I migrated to New York… ran out of newspapers.

ARMSTRONG: Did you have formal training in artwork?

SIMON: No, not really. I migrated from little junior classes in art galleries, local art classes and did sculptures out of Ivory Soap and paintings and so forth. Won some junior awards. They gave us lovely framed prints, which immediately disappeared from my household. I don’t have any recollection, any souvenirs of those days, but they were nice.

ARMSTRONG: So when you got to New York, what did you do? Do you remember when that was?

SIMON: I was 24 when I came to New York. [At] 18, 19—I was working for the newspapers about six years and then I ran out of them in Syracuse and came right to New York. I was getting some art jobs for McFadden Magazines and other… we used to call them flats. They weren’t slicks—they weren’t on slick paper and they weren’t on pulp—but they had very wide distribution. And we used to draw things like teaspoons and other little “spots,” as they called them.

ARMSTRONG: How’d you find out about the comic book business?

SIMON: Well, one of the Art Directors there was a friend of a person named Lloyd Jacquet who ran a company called Funnies, Incorporated. This was at the beginning of the whole comics business. And Funnies would supply art and editorial work for the publishers. Publishers, at that time, didn’t want to invest in their own departments, invest in editors and space, rent space and so forth. So they hired these little companies to prepare the work for them, prepare the insides of the comic books—people who supposedly had worked for the syndicates and knew something about art and story. So, I was sent to Lloyd Jacquet at Funnies, Incorporated and [they] had a little talk with Lloyd. He was an ex-colonel, he worked for a syndicate in New York. This syndicate supplied dailies and Sundays for the newspapers. So Lloyd went out on his own and he was supplying, among other clients, Timely Comics, which was owned by Martin Goodman and was the original Marvel Comics. My first assignment was just

52

conducted & transcribed by David Armstrong

to turn in stuff. You know, they didn’t give a script, they didn’t give me any direction, they said, “Whatever you turn in, if we sell it, we’ll pay you.” I did a western. They didn’t tell me how many pages, though this thing went about ten pages. Lloyd said, “We’ll pay you on publication.” That sounded great because newspapers, you know, publication was the next day. But, as I later learned, publication in comic books was like six months to a year after you did the job. I was new in New York and, you know, trying to get along—that was a problem there.

ARMSTRONG: A problem paying the rent.

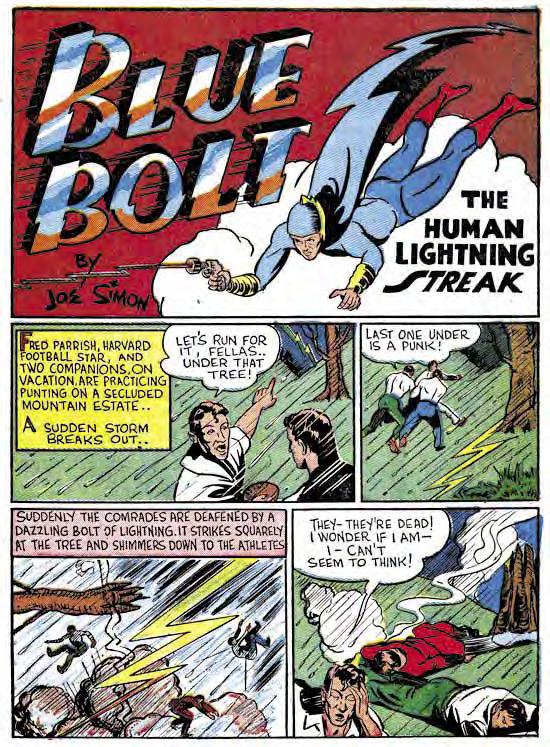

SIMON: Yeah, I had to pay the rent, sure. I lived in Haddon Hall, it was a rooming house, rooming apartment house near Columbia University. Anyway, I did the western. Fortunately, they sold it right away. I have never seen it since, but I know it was published. From [there], I got an assignment from Funnies and the assignment was for what is now Marvel Comics, Martin Goodman. He wanted a strip like the Human Torch—you know, a guy who sets himself on fire and goes out and raises hell. You know, it was okay. I did a strip for him called “The Fiery Mask” and that appeared, that was a late story in Daring Comics, 1940 I believe. Martin Goodman accepted it and published it. I was paid pretty quickly for that, because Martin had a successful operation going. Then, I did a couple more things for Funnies Incorporated. I did something called “Key Man,” which they bought and I never saw it published, but it was published. It wasn’t like today. If you do something for a company, they’ll send you a box of magazines. I never saw the stuff that was done then.

53

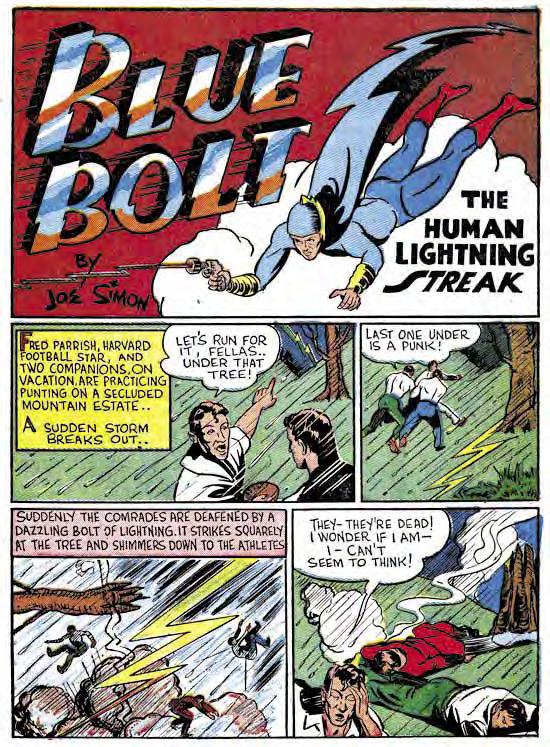

[above] Early Simon photo and illustrations. [right] Blue Bolt #1 and The Fiery Mask.

Kirby Interview, Part 1 INNERVIEW

JAMES VAN HISE: Why did you start doing the crime comics, the non-super-hero comics in the late ’40s, when things were shifting away from the super-hero for awhile?

JACK KIRBY: In the late ’40s, I think we had to [shift]. We were shifting away from the [super-hero] and we began doing Westerns… and I don’t remember if we did any crime comics or not. But we did a thing called Stuntman and Boy Explorers, Boys’ Ranch.

VAN HISE: Like the Headline comics, that was the late ’40s.

KIRBY: Yeah, they came after; after we went to Harvey Comics.

VAN HISE: At that time, did you just generally work for one publisher at a time? Or freelance?

KIRBY: No, we worked for one publisher at a time. When we left Harvey, we had time. We began to work for everybody else. Joe began doing promotional work for Nelson Rockefeller. I began to write a few things on my own. I began to work for DC.

VAN HISE: How did Black Magic come about?

KIRBY: Joe and I were still working together at that time. We worked for Mike Bleier and Teddy Epstein. We worked for Crestwood Publications at the time, and that’s where we did a lot of the comics. We worked for McFadden. We did some pseudo-Archie date comics and romance. They were publishers of romance magazines so I suggested that, what the heck, if we’re doing these date magazines, we might as well do the real thing. And of course romance did very well. Romance is a kind of staple of the people. Just like romance is a staple of any of the media: pictures, pulps, paperbacks.

VAN HISE: Would you contrast your romance comics with what followed as having a different slant?

KIRBY: Our job was to sell comics. The theme doesn’t matter. If you do the theme well, that’s what matters. At the time we worked for Crestwood, we were also competing with EC, which was a very, very good publishing company, and EC was doing very, very well. They had a lot of good men… Harvey Kurtzman, I don’t remember their entire staff, but they were doing a fine job. Of course, we were entering a very bad period, a very bad cycle. That was the time when this fellow, Frederic Wertham, was taking pot-shots at us, and the comic field didn’t have a code and it couldn’t defend itself, and a lot of publishers were finding it hard to capitalize their comics because they were losing sales because of all this bad publicity. And Joe and I began to have our own publishing venture at that time because it was a bad time. But not surprisingly, we put out some very good comics. And we broke even when we might just as easily have lost money. Our comics always sold. We just knew how to do it. We just knew comics.

VAN HISE: Which titles did that encompass?

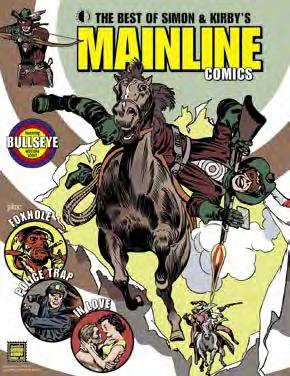

KIRBY: Comics called Win-APrize. We had Police Trap, Foxhole, which was a war comic; we didn’t have super-hero comics. Strangely enough, when we did our own comics, we didn’t have any super-heroes. That was the time actually preceding my split-up with Joe.

58

Conducted by James Van Hise for his article in Comics Feature #34 (1985) Thanks to James, and to Jim Van Heuklon for his assistance in facilitating this transcript

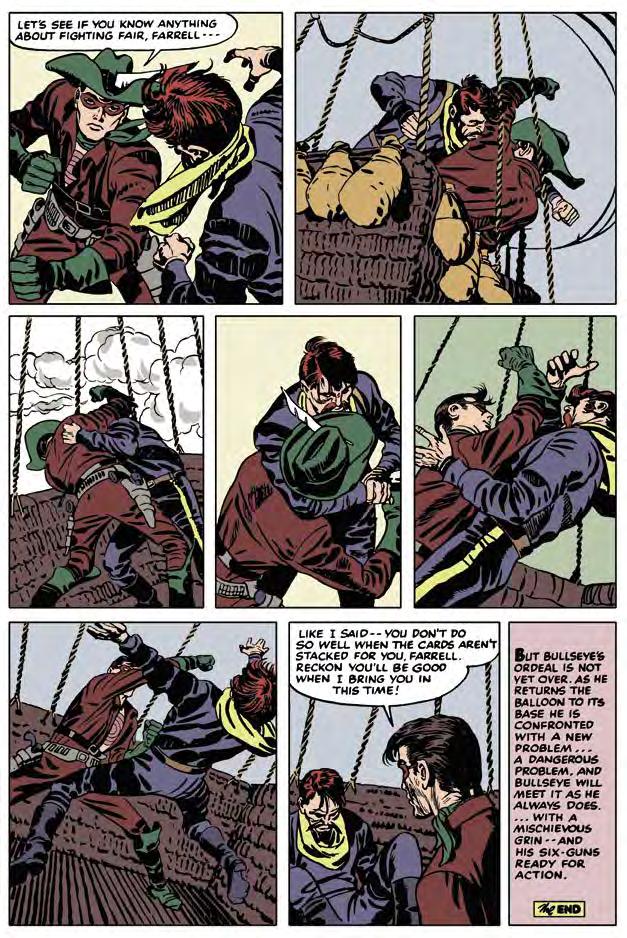

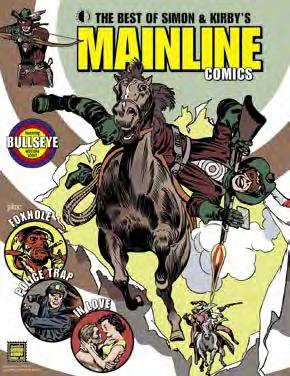

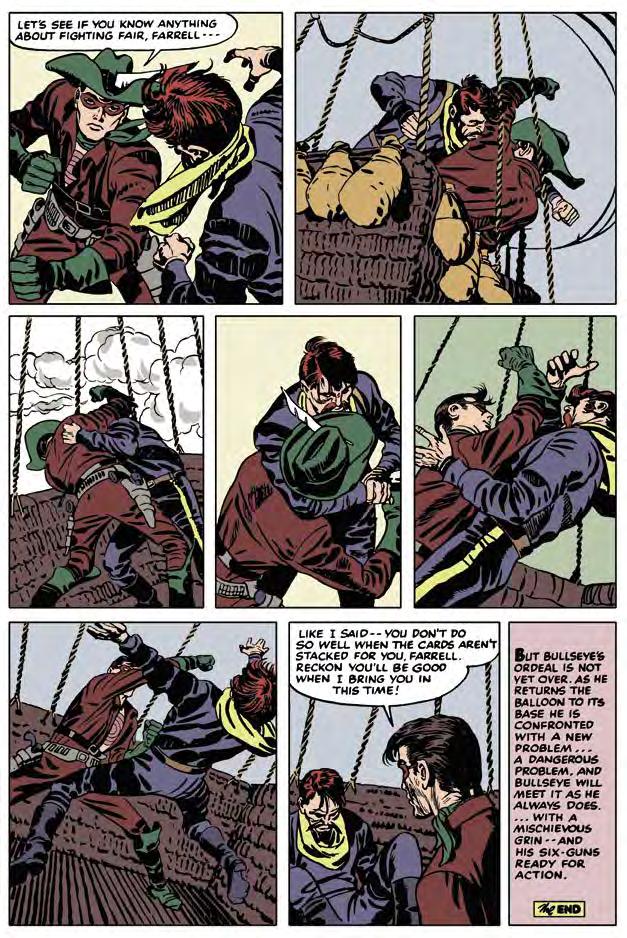

[below] An example of Chris Fama’s restored Bulls-Eye work from TwoMorrows’ new The Best of Simon & Kirby’s Mainline Comics book, out now. It includes a complete reprinting of all the Bulls-Eye stories, as well as all the other Mainline work that featured Joe and Jack’s art, along with select work by other artists, including Mort Meskin.

VAN HISE: You didn’t actually split up with him until, what, later in the ’50s?

KIRBY: Yes. I guess Joe himself may have been soured on the field; I couldn’t blame him. He had some opportunities in the promotional field, which he’s good at, because he was an ex-newspaper man himself. I myself was raised in comics. I’m an editorial man. Of course, I know every idea in the book. So comics was the medium I worked best in and I stuck to it. That’s why Joe went back to doing promotion at Nelson Rockefeller’s; I just went back to do comics. I went to Classics Illustrated where they were so finicky that they drove me crazy, because you had to be so accurate. With the people I had to represent, my goodness, if I had to draw Cleopatra or Ulysses S. Grant, I’d have to know every button, every part of the costume correct, and of course, that’s not my forte. My forte is telling a story. I don’t care whether Cleopatra’s clothes are accurate. I never drew an accurate tank in my life, until later on I began to experiment a little, just because it was fun. I didn’t care about accuracy. I was once criticized for not tying the shoelaces right on a character. He said, “Those shoelaces aren’t tied correctly,” and I said, “Those shoelaces aren’t going to sell the book.” That was my job. My job was selling the book. Whether the shoelaces were tied correctly or not, that book sold. I can’t remember a book that never sold. I sold well, and a lot of other people lost. I’m a good storyteller. I come from a background of storytelling. I do that very well. It doesn’t matter what the story is; if it’s a romance story, I can guarantee it’ll be a good one. Or if it’s a crime story, I can guarantee it’s going to be sincere. It’ll be about people who indulge in crime, not because of any light sense to play around with crime. I’m not interested in that. I’m interested in people. Why do they get caught up in crime? Or why they get caught up in romance—what happens with people when they enter these situations? If they happen to them, they could happen to me. What would happen to me if I was in that situation? Life to me is very real, and so are comic books.

VAN HISE: How did Captain 3-D come about?

KIRBY: That began with a guy named Busy Arnold. Busy Arnold was a publisher who had a company of his own and was the first one to come out with 3-D. And of course, it was a success. It was an instant success. So the Harvey people wanted Joe and me to do a 3-D comic for them, so we did Captain 3-D. And of course, working on a 3-D book is a heart-breaking experience—heart-breaking and back-breaking because the mechanicals involved are very intricate. I couldn’t see a

future in it because I could see 3-D as a toy. I could see putting out one 3-D book, or three, but I can’t see putting out 3-D books steadily. Because initially 3-D books are very hard to read. I gave them my opinion. I said, “This thing is a toy and it’s not going to last.” Besides, I don’t like to do them. They are very hard to do because each panel might require five or six cels. You might do a hand on one cel, you might do a face on another. And of course, we tried to get as much depth as you can. That’s the trick of it. And the more depth you got into the picture, the more realistic the effect. But in reading a 3-D magazine, you have to put all your faculties to work. 3-D work doesn’t pop out at you. You have to pop in. You’ve got to work yourself and of course, you’re not going to do that every month of the year.

59

[above] Unused cover for a proposed 1954 Prize Comic crime title. The public outcry against comics, and the newly-formed Comics Code, likely put an end to this project.

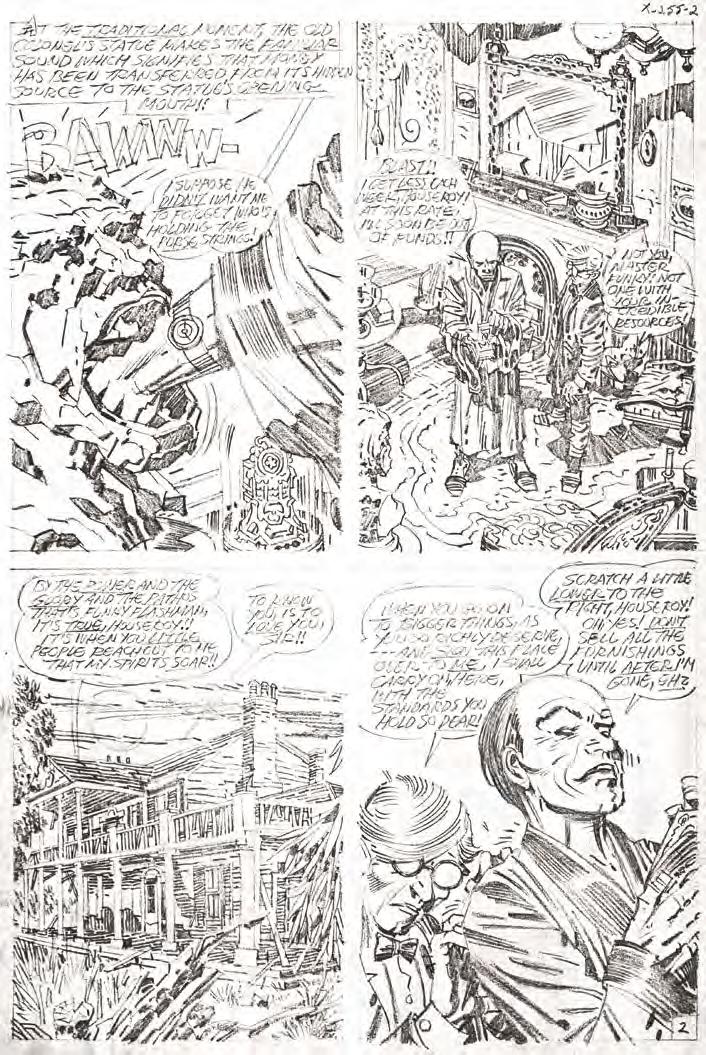

ORDER & CHAOS

Jack Kirby was a profoundly moral man. Coming from an Austrian Jewish background, he often used biblical themes in his stories to give them greater depth and resonance. One such story, done with Joe Simon for Boys’ Ranch #3, is “Mother Delilah.” The story opens in a saloon in a Western town called Four Massacres. We are introduced to a character named Virgil, who is described as “a dreamer and a poet.” He is clearly not someone who has a strong connection to reality, but his name reminds the reader of the Roman poet that had a profound impact on Western literature. In Dante’s Divine Comedy, Virgil appears as the author’s guide through hell and purgatory.

1 Those aspects of the world quickly appear in the person of Curly Yager, a ruffian leading a pack of gunslingers, whom upon entering the bar instantly begins to mock and abuse Virgil. The latter responds in a form of verse which is obviously prophetic. Virgil tells Yager that the mark of Cain is upon him and that he will die by gunfire. Here we have Kirby making Biblical as well as classical references.

2 On page three, we see another Biblically inspired character, the titular Delilah—owner of the bar—chastise Yager for his cruelty. When he turns on her violently, the bar’s bouncer intervenes and is shot by one of Yager’s thugs. Suddenly, Clay Duncan enters the fray and knocks the gunman out.

Duncan is the foreman of Boys’ Ranch, and the overseer of several adolescent boys. One of them, Angel, is a blond, long-haired orphan with a quick temper, and is even quicker with a gun. He is with Duncan during the altercation and speaks critically to Yager, who then makes fun of the boy’s long blond hair. Duncan decks Yager and runs him and his gang out of Delilah’s saloon. She is attracted to Duncan and invites him to dinner, but he politely refuses her advances. Feeling spurned, she decides to punish Duncan by getting close to Angel.

Duncan confronts Delilah about her designs, asking her to stay away from Angel, but she decides not to heed his warning. Angel is lonely and responds to Delilah’s attention, and agrees when she insists on cutting his hair. Like Samson, he is shorn of his golden locks. When he sees what she has done, he is humiliated and feels betrayed. She laughs at his pain and he runs from the house in shame, forgetting to take his guns. 3 Angel is then waylaid by Yager’s gang, beaten and mocked for his sudden impotence, while in the background like a Greek chorus, Virgil speaks the words, “Alas, Samson is betrayed. Delilah’s deed is done. Yet tragic fate still lies in wait with greater woe when sets the sun.”

Gradually, Angel’s hair grows back along with his confidence, and he decides to confront Yager in town. Unbeknownst to him, Angel is followed by Duncan and the other boys. A shootout ensues

63

1 2 3

Barry Forshaw

OBSCURA

A regular column focusing on Kirby’s least known work, by Barry

Forshaw

Barry Forshaw is the author of Crime Fiction: A Reader’s Guide and American Noir (available from Amazon) and the editor of Crime Time (www.crimetime. co.uk); he lives in London.

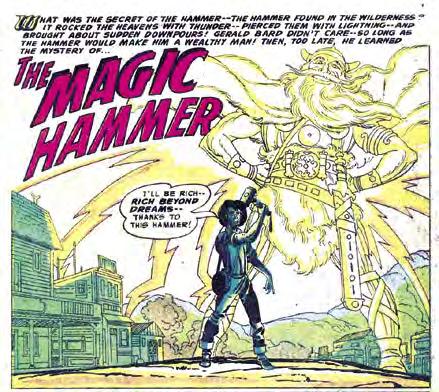

THOR BEFORE THOR

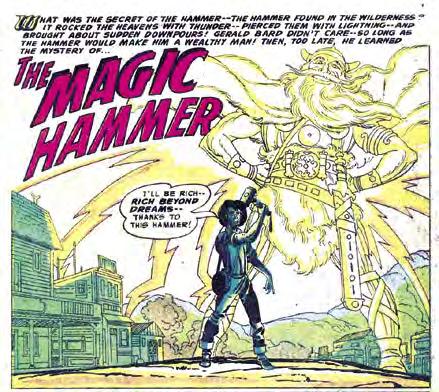

Hitchcock’s various interviews. And as all Kirby enthusiasts know, The King was apt to claim that he was the prime mover of everything in his work, downplaying, for instance, Stan Lee’s contributions. Nevertheless, it’s hard to look at an early piece such as “The Magic Hammer” from DC’s Tales of the Unexpected #16 (August 1957) without seeing it as a precursor of later ideas.

Per Alan Roman Walsh on Facebook:

“On the left a closeup of a Viking from The Adventures of Sir Lancelot Annual #2 (1958) with art by R.S. Embleton.

On the right, “The Mighty Thor” from Journey into Mystery #83 (August 1962) with art from Jack Kirby.” While it’s questionable whether Jack would’ve had any input into Thor’s coloring, the discs on his tunic are awfully coincidental.

There are pleasures accorded to adventurous Kirby enthusiasts who are prepared to look beyond his most popular work from the 1960s onwards—and these are pleasures that have often been noted in this column. What am I talking about? It’s the interest of spotting ideas and themes that Kirby’s amazing imagination came up with earlier in embryonic form which he would later develop more fully (and more famously). Of course, I realize that some of these ideas would be originating from the script writers he worked with, but Kirby famously took everything that came his way and transformed it with his own particular mindset. Examples would include the time travel story for Harvey Comics which he would expand into the Kamandi universe, with animals ruling a dystopian future. And what about this notion? A quartet arrives back from an ill-fated trip into the stratosphere that changes their lives (as the Fantastic Four grew out of the Challengers of the Unknown). There is, of course, a danger of attributing too many of the innovations to Kirby himself and not crediting his collaborators—it would be wrong to echo the syndrome one often found in the work of Alfred Hitchcock, in which the great director was happy for critics to regard his films as almost entirely his work, downplaying (or, more often, not even mentioning) the contributions of his screenwriters—I have the latter info from the horse’s mouth, speaking to Evan Hunter/Ed McBain about his work with Hitchcock on The Birds; he realized that all the things he’d done for the film would not be mentioned in

For a start, the splash panel [below] gives a pretty good indication of what’s going on, with a godlike, muscular Viking figure, fists on hips and wearing a horned helmet looking down on a skinny human character below him holding a hammer—yes, for DC, Jack was drawing an early version of Thor, the God of Thunder, before he turned him into a super-hero under the aegis of Stan Lee. In fact, the entire premise of the story is that the conman hero proves to have access to real power when he discovers Thor’s hammer, which can in fact create rain. But his hubris leads to an encounter with God himself, keen to reclaim his hammer. Two other things look forward to the later Marvel version of the hero: the presence of the mischievous Loki, here a dwarf-like character rather than the more normal-sized brother of the super-hero. But what makes “The Magic Hammer” particularly interesting is Kirby’s design for the hammer itself, which is virtually identical to the later version. The story is drawn in typically impressive Kirby style, and if there is a disappointment, it’s due to the Comics Code censorship of the day—clearly, the criminal protagonist needs a serious punishment at the end, and a few years earlier it would have been death. Here it’s a suggestion of madness, but only the barest suggestion—this character gets off easily after his encounter with Thor. And speaking of this, somebody should sometime put together a book of all these early iterations of ideas that Kirby was subsequently developed compared to the latter. Perhaps the editor of this magazine? Are you listening, Mr. Morrow?

WHERE ARE THE WEAPONS?

Censorship can have some strange effects—sometimes a world away from what the people who wielded the scissors intended. A classic case of this would be James Whale’s original film version of Frankenstein, in which Boris Karloff’s monster advances on a little girl to innocently throw her into a river, just as she has been just doing with flowers—but the cut version (the only one seen by cinema-goers for many years) removed the inadvertent killing and just had a shot of Karloff advancing on the little girl—creating all kinds of different thoughts in the viewer’s minds. When it comes to the Comics Code, however, the effects can often be equally odd. Take “The Terrible Time Machine” from Tales of Suspense #3 (Atlas/Marvel, May 1959). This is a classic example of a tale completely

66

Kirby’s Silver Kid Trail Justice

by Tom Morehouse

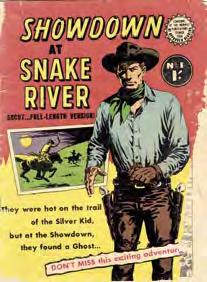

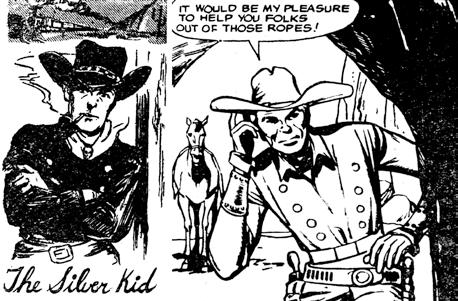

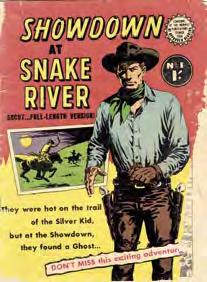

Back in TJKC #60, Rand Hoppe, Executive Director of the Jack Kirby Museum & Research Center, wrote about the rare Jack Kirby western story “Showdown at Snake River”, published only in Australia and Italy sometime in the early 1960s. Not being fluent in Italian, I had been seeking a copy of the Australian version, and I recently acquired one.

There’s some debate among Kirby experts as to the origin of this story. Its inker has been identified by Michael Vassallo as George Klein (inker of Fantastic Four #1) and its job (#0-254) visible in the Italian version, while similar to the Goodman/Lee/Atlas job numbers, is unknown to both Greg Gatlin’s atlastales.com and the Grand Comic Book Database. The most likely explanation is that this was created by Kirby for Atlas, but was rejected for some reason (see further on) and released only to the foreign market. That explanation is backed up somewhat by the fact that there is also a Jack Kirby drawn Black Rider story, “Guns Roar at Snake River”, that only appears in the Australian comics The Fast Gun #9 (1960) and Giant Western Gunfighters #4 (1962). [That story follows this article.]

Whatever the reason, my interest is not so much why it wasn’t published in the US, but rather what inspired Jack to create it. He was a prolific reader of pulps, and loved Hollywood movies, both of which I think played a part in the creation of this tale. The story centers around three men who are traveling to Snake River for different reasons, all of them typical Jack characters and all of them related in some fashion to the same individual, The Silver Kid. One is a dangerous criminal, Hank Kreeger, who is being escorted by the Sheriff to his date with the hangman; the second is a wannabe hot shot gunfighter named Whip McCall, who wants to make a name for himself; and the third is a nerdy-looking bank detective named Artemus Brady. All three are searching for a gunslinger who vanished sometime prior.

There’s also a rancher in Snake River named Jim Hutchinson, his granddaughter Stacey, and a ranch hand called Britt, who was fished out of the river by Jim but has no memory of how he ended up there, nor what his real name is. He is, in fact, The Silver Kid, an outlaw who supposedly pulled off a daring bank robbery before disappearing. Brady, McCall and Kreeger (whose men busted him loose) eventually figure out who “Britt” really is and go after him for their own reasons: Brady to retrieve the bank’s money; McCall to challenge and show he can outdraw The Silver Kid; and Kreeger, who actually robbed the bank in question, but was relieved of the stolen money by The Silver Kid, who planned on returning it.

The story is packed with classic Kirby fight scenes and gunfights, and in the end, the bank payroll is found, Kreeger and McCall both end up dying—Kreeger is thrown from his horse, and McCall is

shot by the Sheriff. Britt is exonerated (when Kreeger confesses as he’s dying, overheard by Brady and the Sheriff) and he and Stacey can begin a life together, leaving The Silver Kid behind forever. That last fact, in my opinion, puts to rest the notion some have posited that this was done as a daily newspaper strip. I can’t imagine anyone going to all the trouble of creating a strip and then having his character, as they say, “ride off into the sunset”!

Now, to the point of all this; what inspired Jack to write and draw this, and why wasn’t it published in the US? Let’s start with Kirby’s inspiration. As I mentioned, Jack was an avid reader of pulp magazines and, in fact, had quite a collection of them. In the early 1930s pulps, there was a drifting, heroic gunfighter named Solo Strant (an odd name for a pulp hero), who was also known by the more conventional nickname The Silver Kid because of the silver buttons on his black shirt, the silver conchos on his chaps, and the band of his black hat, his silver-butted Colts, and the small silver skull that adorns his hat’s neck strap. Author H.W. Ford wrote more than sixty Silver Kid stories between 1935 and 1950. At first they appeared regularly in Wild West Weekly and then eventually migrated over to the Columbia pulps Real

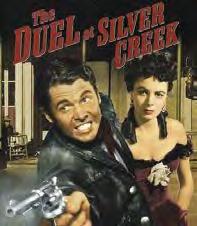

Western, Double Action Western, Western Action, and Complete Cow-Boy. Kirby’s protagonist Whip McCall resembles the pulp illustrations of this character with his classic western eight-button “Bib Shirt.” Jack was also a movie fan, and in 1949, Audie Murphy starred in a film (eerily similar to the title “Showdown at Snake River”) playing a gunslinging character named The Silver Kid. Murphy, the most highly decorated G.I. of World War II, was short in stature, but could hold his own in a fight. I’m pretty sure Kirby could identify with that, and while I can’t prove it, I’d be willing to bet Jack saw that film in which The Silver Kid ends up working on the side of law and order, gets the girl, and gives up gunfighting.

In “Showdown at Snake River”, Jack Kirby was writing the final chapter to the Silver Kid story. He was, in essence, wrapping up the two threads (pulps and the movie), conveniently never revealing “Britt”’s real name. What Kirby didn’t do much of was read competitors’ comic books, so he may not have known that there was a Silver Kid Western comic published by Stanley Morse in the mid-1950s. Stan Lee, on the other hand, was no doubt aware of it, as part of his job

(84-page FULL-COLOR magazine) $10.95 (Digital Edition) $4.99

https://twomorrows.com/index.php?main_page=product_info&cPath=98_57&products_id=1692

68

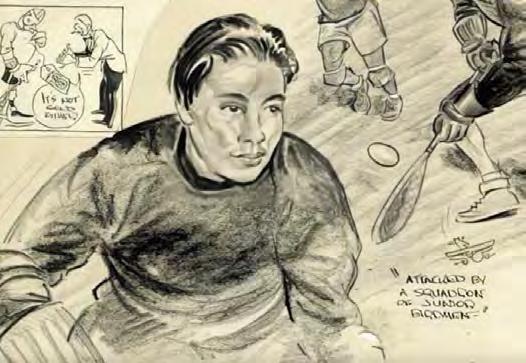

The Silver Kid of the pulps (left), and Jack’s version.

Britt Harmon.

IF YOU ENJOYED THIS PREVIEW, CLICK THE LINK TO ORDER THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DIGITAL FORMAT!

KIRBY COLLECTOR #87

LAW & ORDER! Kirby’s lawmen from the Newsboy Legion’s Jim Harper and “Terrible” Turpin, to Western gunfighters, and even future policemen like OMAC and Captain Victory! Also: how a Marvel cop led to the creation of Funky Flashman! Justice Traps The Guilty and Headline Comics! Plus MARK EVANIER moderating 2022’s Kirby Tribute Panel (with Sin City’s FRANK MILLER). MACHLAN cover inks.

by Richard Kolkman

by Richard Kolkman