Reindeer hunter with bow and arrow (low, left) in the prehistoric Alta rock art. Photo: Per Storemyr

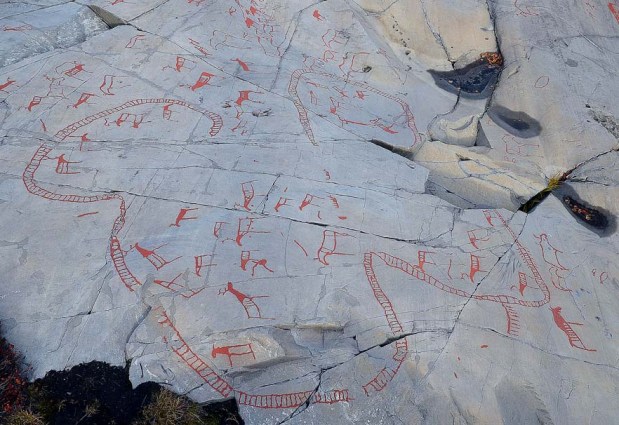

Earlier this week I attended a workshop on conservation of the prehistoric rock art at Alta in Northern Norway. This gave me the opportunity to take a closer look at the great Stone Age panels in the Hjemmeluft area, which is one of five major areas with rock art at the bottom of the extraordinarily scenic Alta Fjord (overview in Tansem & Johansen 2008). Discovered only some 50-60 years ago, the rock art at Alta became inscribed on the World Heritage List in 1985. It is the greatest concentration of rock art in the north of Europe, covering the period from the Stone Age to the Iron Age, or from c. 7000 to c. 2000 years ago. This is truly fascinating hunter-fisher-gatherer rock art, not least because many scenes may have their parallels in much younger, indigenous Sami practices and beliefs. Below is a collection of images and scenes – and landscapes – that particularly impressed me.

The rock art at Hjemmeluft consists of some 3000 images situated at both sides of a broad bay at which the World Heritage Rock Art Centre – Alta Museum is also located. The bay appears not only to have been a favoured place for making rock art in prehistory, but also for living. There are several habitation sites of nomadic people, many of which are contemporaneous with the rock art.

The Hjemmeluft rock art site as seen towards the north from Alta Museum. The rock art is located at both sides of the bay. Photo: Per Storemyr

The Hjemmeluft site has been open to the public for several decades and a wonderful system of raised pathways makes it an experience to enjoy the most important panels. Also, most of the rock art is very easy to see since it has been painted in red by conservators. Heavily disputed, such painting is a Scandinavian practice aimed at making the rock art accessible to the public. For many it may appear as vandalising the rock art, but it ought to be remembered that Scandinavian rock art is extremely prone to rapid lichen growth, which makes it very difficult to “read” the pictures. Thus, in addition to brushing away lichen and painting the rock art red, many sites at Alta, and generally in Norway, are regularly treated with pure alcohol to keep lichen away; after a few years lichen tend to die from alcohol abuse! But whether this practice will have any long-term, negative effect is not known.

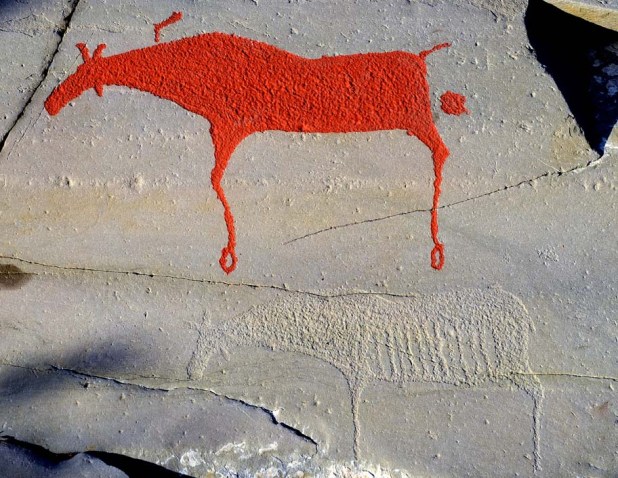

Anyway, take a look at the elks below. They are at least 6000 years old. Moss and lichen have been removed from the alcohol-treated bedrock, one elk is painted, the other not. When the sun is low, giving a raking light, it is easy to see the non-painted, pecked elk. But in the common, overcast Scandinavian weather the non-painted elk would have been extremely difficult to distinguish…

The Hjemmeluft site. More than 6000 year old, pecked elks; one has recently been painted in red, the other not. Over the last few years the rock surface has also been regularly treated with alcohol to keep lichen away. Photo: Per Storemyr

Eurasian elk (as opposed to the North American moose) is the largest member of the deer family and has been a favoured animal in hunting practices for thousands of years. Thus, it is no wonder that it takes such a prominent place in the Alta rock art.

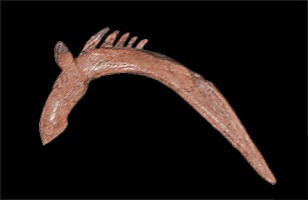

A c. 40 com long elk-headed pole made from bone from a 7500 year old burial site in Russian Karelia. Digitally enhanced photo of poster exhibited at Alta Museum.

Interestingly, elk is commonly depicted close to human figures often holding a stick or a kind of pole, almost looking like a boomerang. It is uncertain what type of object this really is, but it has tangible parallels, so-called “elk-headed poles” made from bone that have been found in Stone Age contexts in Russian Karelia. Did it have a practical function, for example as a weapon, or is it a ritual object – or both?

Elk and human connected with a so-called “elk-headed pole” in the Alta rock art. It is not known what the pole may represent. And what about the structure below the elk? Is it a pit so commonly used in elk hunting almost up till today? Photo: Per Storemyr

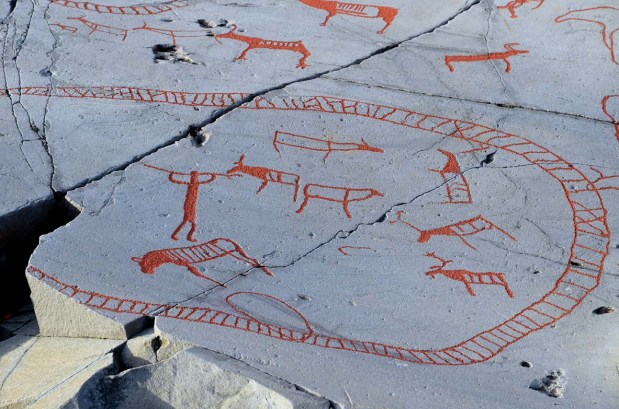

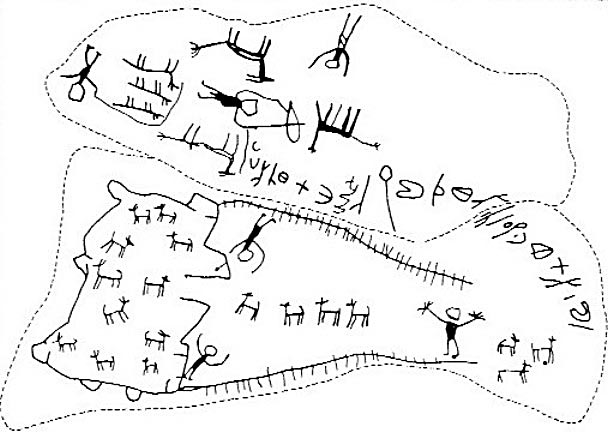

Reindeer is more prevalent than elk in the rock art up here in the far north. And since I’m working with ancient, permanent hunting structures in Egypt and Nubia, I certainly found it intriguing that there are several depictions of reindeer corrals at Alta. According to Knut Helskog (2011) the corrals are between 6000 and 7000 years old and depict real corrals just as they have been used until today for driving in and collecting reindeer to be slaughtered and perhaps also to separate animals to be used for transportation. It is, however, uncertain whether reindeer was domesticated e.g. to be used for transport using sledges at such a very early stage; some researchers (Sommerseth 2011) seem to imply that this happened only in the late Middle Ages (AD 13-1400). Moreover, as Helskog underlines, corrals in Stone Age rock art is something much more than a representation of real constructions; their depiction is certainly interwoven with rituals, myths and narratives that are difficult for us to comprehend.

Human with spear apparently killing reindeer within part of the large corral at the panel Bergbukten I at Alta. Beside the human is also an elk. Photo: Per Storemyr

There are similar depictions of hunting corrals and enclosures in rock art throughout the world. Examples that I’m familiar with include the famous “desert kites” in the Near East (Betts & Helms 1986, see also recent overview of real desert kites in Holzer et al. 2010). These were used for hunting large herds of gazelle since at least the Neolithic. Below is a depiction of such a hunt in Jordan which is about 2000 years old.

A rock art hunting scene from Jordan, c. 2000 years old. Gazelle is being driven along leading lines into the central corral. Such a construction is popularly called “desert kite”. Picture from the Megalithic portal, originally recorded by G.L. Harding (The Cairn of Hani, Antiquity 28, 1954: 165-7).

A different type of permanent hunting devices is found in Epipalaeolithic Egyptian rock art. Studied by Dirk Huyge (2009, page 8), these more than 8000 years old depictions most probably represent fish traps – of a form that have been used in fish hunting until today in different parts of the world.

Mushrooms? Penises? No, these are depictions of more than 7000 year old fish traps at el-Hosh in Upper Egypt. Arrows indicate the movement of fish to be trapped. Photo: Per Storemyr

So, how can we be so sure that the rock art at Alta dates back to the Stone Age? The key is the uplift of the land after the last ice age. Though still a matter of debate, it seems that the sea level at Alta some 7000 years ago was about 22-25 metres higher than today (Helskog 2011, Gjerde 2010). Also, it seems very likely that the rock art was made just above or even within the tidal zone since this would have been totally free of vegetation, especially lichen, just as today. Moreover, this zone is not covered by snow during the long arctic winter, implying that the pictures may have been accessible to prehistoric man year-round. But the perhaps most important reason for carving rock art in the tidal area is that it may have represented a liminal zone for prehistoric man; the transition between the heavens, this world and the underworld – a distinction that is also very prevalent in Sami religious concepts.

Rock art sites at the western part of Hjemmeluft. There are three visible levels as indicated by the light, lichen-free rock above the current shore line. These levels represent ancient shorelines that can be dated. Photo: Per Storemyr

Interestingly, in the contemporary tidal zone at Alta the glacier-scoured rock has a reddish-brown patina, quite different from the natural greenish-greyish colour of the Precambrian, metamorphic sandstone bedrock. The colour appears to be a result of oxidation of iron present in the bedrock, but only in the slightly alkaline zone with sea spray. Further up, moss and other vegetation render the surface of the bedrock too acid for such patina to form – and it also dissolves previously formed iron-rich patinas. Thus, it is very likely that the Stone Age rock art was pecked cutting through the very thin patina, implying that the images must have stood out as very light on the red background. It is just the same as when people in desert areas took advantage of dark desert varnish on bedrock when making rock art.

The current shoreline in at Alta, with reddish patinated bedrock. The surface features of the rock is otherwise a result of ice-scouring during the last Ice Age. The natural colour of the rock can be seen in the areas with exfoliation. Photo: Per Storemyr

Pecked giraffes on sandstone with dark desert varnish. Aswan, Upper Egypt, 4th millennium BC. This is close to how we may imagine rock art at Alta when it was made: Light figures on a darker background. Photo: Per Storemyr

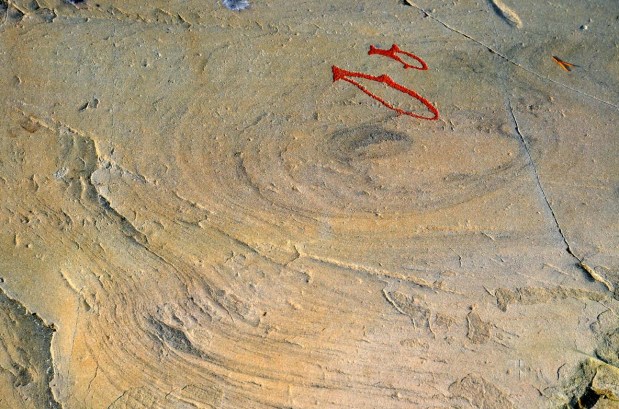

When the rock art panels at Alta were thoroughly cleaned from lichen, many other interesting connections between bedrock and images were found. It would seem that the makers of the rock art did not only take advantage of the micro landscape with its depressions, ridges and cracks to place the images, but perhaps also slightly shifting bedrock colours, defined by changing mineralogical composition in individual sedimentary laminae (Tansem 2011, in the book “Fersk forskning, nye turisme, gammel bergkunst“). At places shifting bedrock colours may have been visible through the reddish patina, at other places not.

The bear dens and associated tracks and bear figures are a very special feature of the Alta rock art (see e.g. Helskog 2004, page 273ff). Like in Sami world views, the bear must have been an animal of enormous cultic importance for the makers of the rock art. And, interestingly, it is in association with bear images that we find the most easily recognisable natural features used in rock art compositions. Take a look at the picture below: At the right hand of the picture there is a depression with laminae of alternating colours. Here is also a double circle from which lines of small dots appear “up the valley”. Looking closer, it can be seen that these dots must represent bear tracks, since they stop at the left side of the picture, just where a bear hunt is taking place. Thus, the double circle seems to represent a bear den, from which the animal went out after the winter sleep – and got caught.

In the left part of the picture is a similar scene, enhanced with green, since it is difficult to see the bear tracks. Here the bear does not come out of an image of a den, but of a natural, circular feature.

Bear hunting scene at the panel Bergbukten I: The bear has gone out from the circular feature to the right and is hunted at the left. Enhanced in green: A natural rock feature forming a bear den, from which tracks appear. Photo: Per Storemyr.

The thin laminae in the Alta bedrock may invoke much imagination. What about the image below? Is it depicting two small whales (porpoise) swimming down a maelstrom?

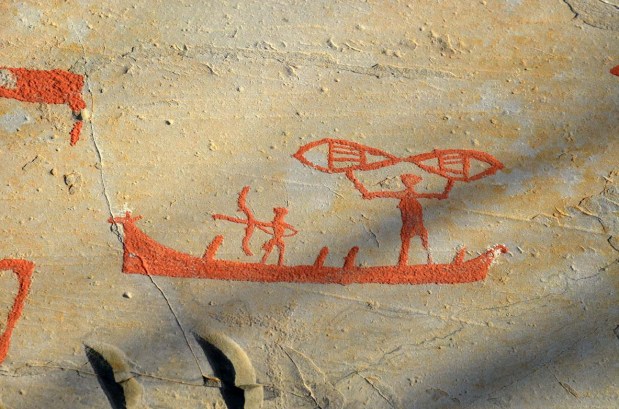

There are many other themes in the Alta rock art. Boats, for example, appear around 6000 years ago. There are different types of boats, some of which were used for hunting with bow and arrow, perhaps in order to catch reindeer driven into the sea. The boats would have been made from skin and in the Alta Museum there is a great reconstruction of how they may have looked like.

Hunting with bow and arrow from a skin boat with its prow formed as the head of an elk. The human with raised arms is probably holding a pair of snow shoes. Photo: Per Storemyr

Reconstructed Stone Age skin boat with elk-headed prow in the Alta Museum. Digitally enhanced photo: Per Storemyr

Depictions of snow shoes attest to the arctic landscape this rock art was made in. But there is more; one figure seems to have skies on hunting elk! A testimony of the long skiing traditions up north!

The Alta rock art will never cease to fascinate. Go and take a look for yourself, beginning at the website of World Heritage Rock Art Centre – Alta Museum.

And thanks a lot to archaeologists at the museum – Martin Hykkerud, Lars Julsrud, Hans Christian Søborg and Are Skarstein Kolberg – for making my stay in Alta unforgettable!

Map