Secret Japanese Military Maps Could Open a New Window on Asia's Past

The recovered maps provided valuable intelligence for the United States after World War II.

These maps were captured in the waning days of World War II as the U.S. Army took control of Japan. American soldiers confiscated thousands of secret Japanese military maps and the plates used to print them, then shipped them to the United States for safekeeping.

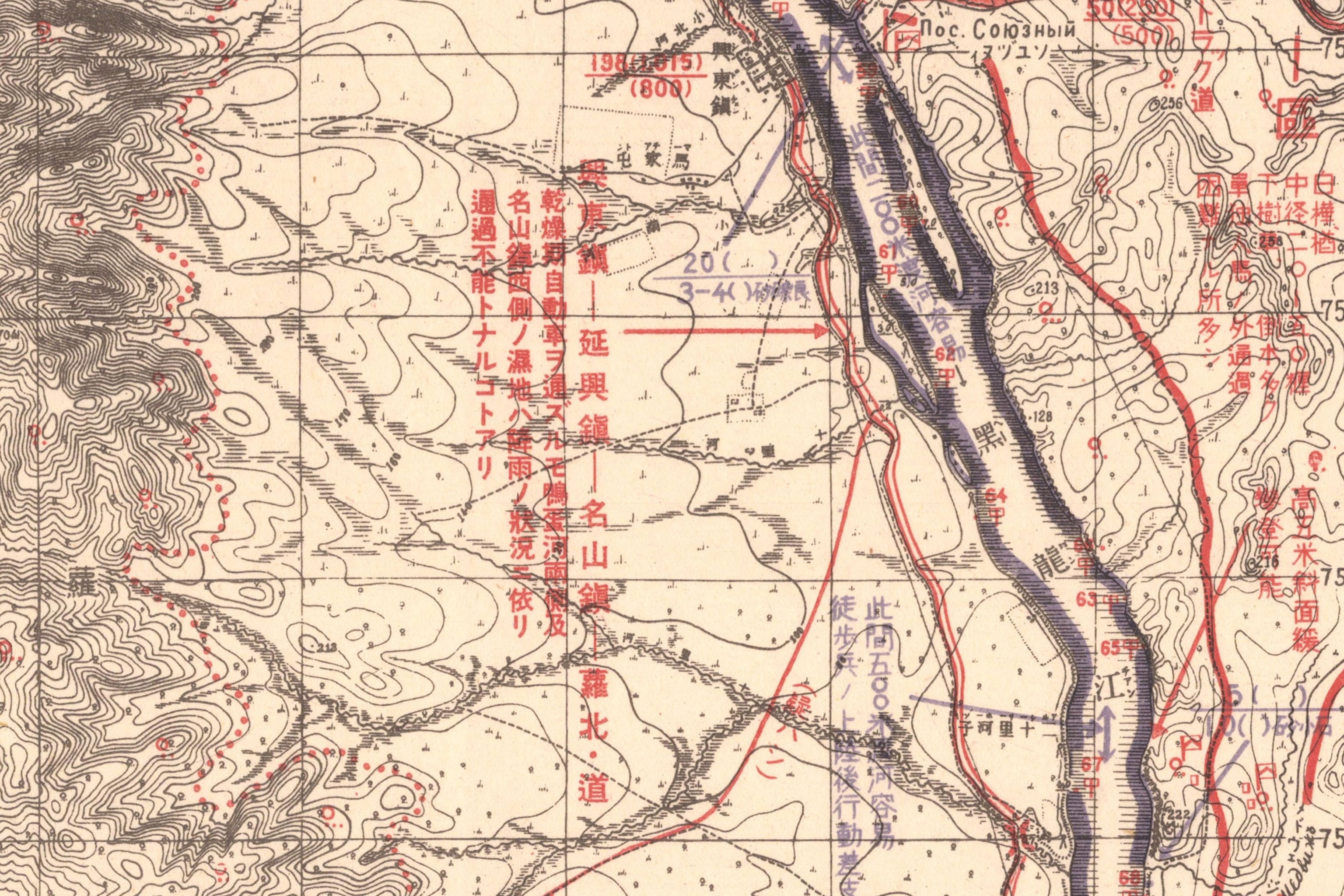

The maps covered much of Asia, and they went far beyond the local topography. They included detailed notes on climate, transportation systems, and the local people. It’s the kind of information that could be used to plan an invasion or an occupation, and some of it was gathered by spies operating behind enemy lines. To the Japanese, these maps are known as gaihōzu—maps of outer lands.

To the Americans, they were a valuable source of intelligence, not just on a recently defeated foe, but also on a newly emerging one—the Soviet Union. The Army Map Service considered it unwise to hold such an important strategic resource at a single location that could be wiped out in a nuclear strike, so it distributed the maps to dozens of libraries and institutions scattered across the country.

And there they remained, virtually forgotten, for decades.

Now, slowly, they’re starting to be rediscovered by scholars who are interested in using them to study the geopolitical and environmental history of Asia. “They’re a treasure for historical research,” says Kären Wigen, an East Asian historian at Stanford University.

About eight years ago, a Stanford graduate student named Meiyu Hsieh started asking around about some rumors she’d heard about mysterious stacks of old Asian maps amid the extensive archives of the Hoover Institution, a think tank that occupies a prominent tower on campus. Hsieh's dissertation explored why the ancient Han dynasty was able to build the first large, enduring empire in China more than 2,000 years ago. But many of the relevant archaeological remains have disappeared from the surface, either eroded away over time or covered up in the process of China’s industrialization, and don't appear on modern maps and satellite imagery, says Hsieh, who’s now a history professor at Ohio State University. Older maps, Hsieh reasoned, might hold some important clues.

Eventually her queries led her to a dark room lined with drawers in the basement of Branner Earth Sciences Library. “I spent an afternoon pulling out all the drawers, trying to figure out what was there,” she says. What she’d discovered, or rediscovered, was the university’s cache of Japanese military maps, which had been moved to Branner years earlier from the dusty attic of Hoover tower.

The head librarian at Branner, Julie Sweetkind-Singer, made a deal with Hsieh: She could use the maps for her research if she helped the library get a start on organizing its collection and figuring out what it had. It had, it turns out, roughly 8,000 of these maps.

To learn more about what it had in its collection, the library organized a conference in 2011 and invited the leading Japanese expert on these maps, Shigeru Kobayashi, now an emeritus professor at Osaka University in Japan. Until then, Kobayashi’s research had only appeared in Japanese, but for the conference he wrote a paper that detailed their history for the first time in English.

Beginning around 1870, Kobayashi wrote, the Japanese military began making maps of neighboring countries. At first, they copied maps obtained from those countries or from the West. But army officers soon realized they needed better maps and began sending teams to survey first the coastlines and then inland areas of China and Korea.

The late 19th century was a fraught period in Japanese history, says Stanford’s Wigen. Elsewhere in the world, the imperial powers of Europe were busily carving up Africa. “Japan wanted to be a power; they certainly didn’t want to be carved up,” Wigen says. “It looked like those were the two choices: Either you acquire a colony or you become a colony.”

Not surprisingly, the Japanese surveyors weren’t always welcomed in other countries. In 1895, angry locals in Korea killed several assistants on a Japanese survey team, Kobayashi writes. (Japan annexed Korea in 1910 and held it until the end of World War II.) Two decades later, Japan sent secret survey teams into China. These men disguised themselves as traveling merchants and made their maps equipped only with a compass and by counting their steps to mark distance.

In the age-old tradition of cartographic copying, the Japanese often built on maps they’d captured from their foes, adding their own notes and details on top of the original. Cyrillic script is visible in the Japanese map above of Vladivostok, Russia, for example. Naturally, their enemies did the same thing. The formerly classified U.S. Army map of Okinawa below, printed in 1945, is based on a captured Japanese map.

The quality of the gaihōzu improved over time, and the types of maps became more diverse, says Wigen, who recently co-edited a book on the cartographic history of Japan. In addition to topographic maps showing the terrain of other countries, the Japanese military made everything from aeronautical charts to city maps showing who lives and works in different neighborhoods (as with the map of Shanghai near the top of this post). Many of these maps contain detailed notes in Japanese on features that might be of strategic value—things like the suitability of a coastline for landing boats or the locations of factories used to make weapons. One map of a South Pacific island includes notes on the local diet and the location of the island’s only ice machine.

Stylistically, the maps are remarkably diverse, a fact that did not escape the notice of William E. Davies, the chief of research at the Army Map Service in the years after World War II. “During the war Americans and British tended to standardize the style and design of most maps, often carrying the uniformity to a point approaching stereotyping,” Davies wrote in 1948. “The Japanese were just the opposite in this respect, for each series of maps that was produced was designed to fit an individual condition and as a result the maps show a variety of colors, symbols, and format.”

The area covered by the gaihōzu extends as far north as Alaska and Siberia in the north, as far west as India and even Madagascar, and as far south as Australia. No one knows how many maps were made, mostly because the military kept its mapping program secret and ordered the maps destroyed as the U.S. Army closed in at the end of World War II.

Stanford has so far led the way in scanning these maps—7,353 at last count—and the university is putting them online for anyone to explore or download. Tohoku University Library in Japan also has a large online collection, indexed in both Japanese and English. (The maps that survive in Japan were apparently saved by cartographers who’d devoted their careers to making them and defied orders to destroy them, Kobayashi says.)

The gaihōzu have lost their strategic value with time, but researchers like Kobayashi and Hsieh still see them as a valuable resource. Kobayashi is interested in using them to study deforestation and other types of environmental degradation. “Looking at gaihōzu opens the way to studying how landscapes have changed in Southeast Asia and China,” he says.

Many thanks to Shizuka Nakazaki at Stanford and Shigeru Kobayashi at Osaka University for locating the maps used in this post and aiding with translation.

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- How scientists are piecing together a sperm whale ‘alphabet’How scientists are piecing together a sperm whale ‘alphabet’

- Orangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first timeOrangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first time

- What La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planetsWhat La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planets

- This fungus turns cicadas into zombies who procreate—then dieThis fungus turns cicadas into zombies who procreate—then die

Environment

- The northernmost flower living at the top of the worldThe northernmost flower living at the top of the world

- This floating flower is beautiful—but it's wreaking havoc on NigeriaThis floating flower is beautiful—but it's wreaking havoc on Nigeria

- What the Aral Sea might teach us about life after disasterWhat the Aral Sea might teach us about life after disaster

- What La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planetsWhat La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planets

- How fungi form ‘fairy rings’ and inspire superstitionsHow fungi form ‘fairy rings’ and inspire superstitions

- Your favorite foods may not taste the same in the future. Here's why.Your favorite foods may not taste the same in the future. Here's why.

History & Culture

- These were the real rules of courtship in the ‘Bridgerton’ eraThese were the real rules of courtship in the ‘Bridgerton’ era

- A short history of the Met Gala and its iconic looksA short history of the Met Gala and its iconic looks

Science

- Why trigger points cause so much pain—and how you can relieve itWhy trigger points cause so much pain—and how you can relieve it

- Why ovaries are so crucial to women’s health and longevityWhy ovaries are so crucial to women’s health and longevity

Travel

- What it's like trekking with the Bedouin on Egypt's Sinai TrailWhat it's like trekking with the Bedouin on Egypt's Sinai Trail