Malcolm McDowell, formerly of Leeds, Liverpool and London, now lives in Shangri-La. Almost literally. We meet on the terraced restaurant of a country club near his house in Ojai, up the freeway from Los Angeles and then inland to a spectacular valley overlooked by bluffs and crags that seem vaguely reminiscent of the mountains in Powell and Pressburger's Black Narcissus. But I'm one Himalayan movie off, it turns out.

"This is where I've lived since 1982," he says, with some pride. "We live over there, on Meditation Mountain. It's where they put the camera for the shot of Shangri-La that they matte-painted into the 1937 version of Lost Horizon. The blue screen of its day, that view is!"

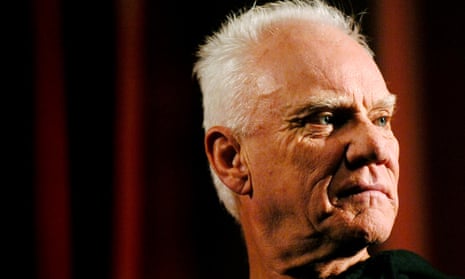

McDowell's face, at 64, has lost the rounded, meat-and-milk contours of his beautiful youth, but has gained sharper, more chiselled planes that echo his still lean and athletic physique. The enormous blue eyes that Stanley Kubrick had wired open for A Clockwork Orange don't shine quite so brightly these days, but only because his splendid shock of white hair provides less contrast than it did when it was brown. It's still a great punk-rock face: tough and seemingly born for villainy and swaggering mayhem (or so an unimaginative casting director might think), but always bisected by that famous sideways grin, the smile that made Caligula, Harry Flashman, even his psychopathic Nazi in the long forgotten The Passage, seem possessed of infinite charisma.

He moved here with his second wife, the actor Mary Steenburgen. "I came to make a movie in 1979 [the time-travel thriller Time After Time], fell in love, stayed, then we had children. But when we split up in 1990, the die had been cast. Obviously, I wasn't going to move away from our children. I had never thought about moving here, it just sort of happened that way." He admits that he misses England on occasion - or rather the people. "But once you get back there," he laughs, "it's immediately, 'Get me the fuck OUTTA HERE!'"

The second act of McDowell's career has been a busy and remunerative life as a Hollywood character actor - there may be more people in the US who remember him as the murderer of Captain Kirk in Star Trek: Generations than as insurgent schoolboy Mick Travis in If ...

But we're here to talk about the earlier, British half of his career, and of his association with the director of If ..., O Lucky Man and Britannia Hospital, who discovered McDowell 40 years ago and remained a close friend until his death in 1994: Lindsay Anderson.

A year or two ago, McDowell conceived a one-man stage show as a tribute to Anderson and performed it in a nearby schoolhouse. His lifelong friend Mike Kaplan, who has worked as a publicist for Stanley Kubrick, Robert Altman and others, and as a producer for director Mike Hodges, had the show filmed, resulting in Never Apologise, which opens tomorrow.

It's an intimate piece of work, with a loose, handmade feel and the sense of an obligation fulfilled, a debt repaid with honour and gratitude. McDowell shares his memories of working with Anderson, and of the tight little community the director built around him, in which moneyed superstars of stage and screen existed on an enforced equal footing with whatever misfits, unemployed actors, mad writers and other broken-winged birds were nesting in Anderson's spare room. He recalls Anderson's (and his own) friendships with Rachel Roberts, Jill Bennett, Alan Price and Ralph Richardson, reads from Anderson's monograph, About John Ford, his cinematic idol, and, most memorably, from a lyrically aggressive letter to Alan Bates from Anderson, in which the director sort of apologises for some ancient drunken insult, even as he dismisses the entire notion of apologising.

Never Apologise is a looser companion piece to the late Gavin Lambert's beautiful memoir Mainly About Lindsay Anderson. In that book, the core sadness of Anderson's life - a tremendously gifted artist, a lacerating critic, a repressed, unhappy, celibate homosexual who may have died a virgin - is alleviated somewhat by the parallel account of Lambert's almost diametrically opposed passage in life from the same junior common room at Cheltenham College in the 1930s: contentedly out of the closet all his life, in love with exile in California, emollient rather than abrasive, happy in his skin. Never Apologise works in a different register, but again Anderson's pessimism and misanthropy are made palatable by the obvious love and admiration of an old friend.

I've brought my copy of Lambert's book along with me, and McDowell flips eagerly though the photos in search of what Anderson called "The Old Crowd", all the dead old friends.

"Look, there's Tony Page and Jocelyn Herbert - she took a lot of shit from Lindsay, and gave just as much back!" We both pause when we arrive at a famous picture of Rachel Roberts and Jill Bennett in their fur coats; doomed, gifted, insecure princesses of the London stage, both married to bastards (Rex Harrison and John Osborne respectively), both suicides.

"Gavin's thing about Lindsay," says McDowell, "was always, 'Why doesn't he just come out? Why doesn't he just get himself fucked? Lindsay needs to be buggered!' Course, he'd say it to me - but he'd never say it to Lindsay! But Gavin said Lindsay never would have made If ... if he hadn't been exactly what he was. Because he was this pent-up creature, very sardonic, and a very suppressed human being. And he had that very English thing, he hated the English, but of course, he WAS English, more English than anyone I've ever known. Lindsay could only have come out of his particular kind of pain. But you never saw this because he was very defensive, which made him laceratingly lethal. He could smell bullshit five miles away and if you tried to bullshit him, well ..." McDowell mimics a series of rapier slashes in the air, bringing Flashman and Mick Travis to mind for a moment.

If ... was finally made available on DVD last year and McDowell is ecstatic about the DVD of O Lucky Man that Warner Bros will release soon. "It's the most pristine print of it I've ever seen," he says. I never manage to ask him about it, but it must be galling for an actor as talented as McDowell to have waited this long for two of his career cornerstones to become available in his adopted country, where he is mainly renowned for A Clockwork Orange.

What were the differences between Anderson and Kubrick?

"Chalk and cheese. Kubrick was at the top of his game. I think I worked with him when he was 47, the same age Lindsay was when I did If ..., also at the height of his powers. Stanley, however, was not really a people's person; he didn't like a lot of talk about acting. Lindsay loved to talk shop: if you asked him about a role, it'd be two hours, a great discussion of history, character, framework and psychological things. But Stanley, you'd ask him something and he'd look at you, say, 'I'm not Rada,' and walk off.

"But there was something very liberating about that. At first I was very pissed off - 'You've got to be kidding!' - and then you realise he's just given you an almighty present - you can do whatever you want.

"Then, when I was back with Lindsay on O Lucky Man, I would say, 'Don't talk to me, I know what I want to do!' So the tables had turned a bit since If ..., and he had plenty to say in his diary about it. 'I'm very pissed off with Malcolm - thinks he knows it all!'

"But Kubrick could be very spontaneous, surprisingly, and I picked that up from him. Stanley at his best was at the head of a giant army, like Patton, but still he was brilliant at being able to say to suggestions, 'That's a great idea!' and telling the whole army, 'We're all going THIS way now!' And off we'd go. While with Lindsay's movies, exactly the opposite, you didn't change a word."

And did Kubrick put you through 500 takes per shot?

"No, I think that started later. I think he lost some of his confidence later, but he still had it in 1971. Stanley would have been quite happy to make a film without actors - and with the Artificial Intelligence project, he nearly did. He always thought they couldn't be relied on. He once asked me if he should send the script girl to Patrick Magee's house and go over his lines with him. I mean, this is Patrick Magee. Samuel Beckett's favourite actor! 'Not if you want a happy actor in the morning!' I said. There was a lot about actors that Stanley wasn't interested in."

"I don't think Stanley and Lindsay ever met, but if I wanted a bit of fun I would sometimes pit one against the other, for my own amusement. I'd go to Lindsay, 'I never have this problem from Kubrick, one of the world's greatest directors, and a populist director at that! Makes films that people want to see!'

"Lindsay would say, 'He's far too cynical for me,' and I'd say, 'Look who's talking! What is the difference between you and Stanley?' He'd go, 'I am a humanist. He is a satirist.' I think that is exactly the right distinction - Lindsay was always right"

· Never Apologise: A Personal Visit with Lindsay Anderson is at BFI Southbank, London, from tomorrow until November 18. Box office: 020-7928 3232.